Inability to pay, rather than abdication of responsibility, seems to be the source of most of the College's problems with the repayment of student loans. The situation is causing some concern but no immediate alarm to Kenneth Cucuel, director of loan programs.

An unmarried alumnus, making $10,000 a year, Cucuel estimates, will have left - after taxes, food, rent, clothing, life insurance, and payments for such as furniture - only about $50 a month for entertainment and other expenses. Under each of the government-sponsored loan programs, Federal Insured Student Loan (FISL) and National Direct Student Loan (NDSL), the repayment rate has been set at a minimum of $30 monthly. A student with a loan package combining the two, therefore, will owe at least $60 a month starting shortly after graduation. In other words, he or she would be spending more than the "typical" $10,000 paycheck provides.

Where some institutions are encountering alumni who claim bankruptcy in order to avoid repayment, the problem is all but non-existent here. Of the ten to 15 bankruptcies Dartmouth has dealt with, only one involved a recent graduate, a member of the Class of 1972. The remainder are spread over older classes, and Cucuel characterizes them as legitimate bankruptcies, not connected with intentional student-loan defaults.

Money is still due on two loans, totaling $250, granted to members of the Class of 1950. This sum is included in the July 1976 total of $8,289,800 outstanding - more than $7 million loaned to undergraduates the rest to students at Tuck, Thayer, and the Medical School.

The College has on occasion taken presumably intentional defaulters successfully to court, but it is generally understanding with alumni who offer a convincing plea that they are having a tough time making ends meet and are not just avoiding repayment. Most of the outright refusals to repay, Cucuel finds, come from alumni who borrowed the money when collection wasn't taken very seriously They tend to claim that they simply don't owe the money any more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

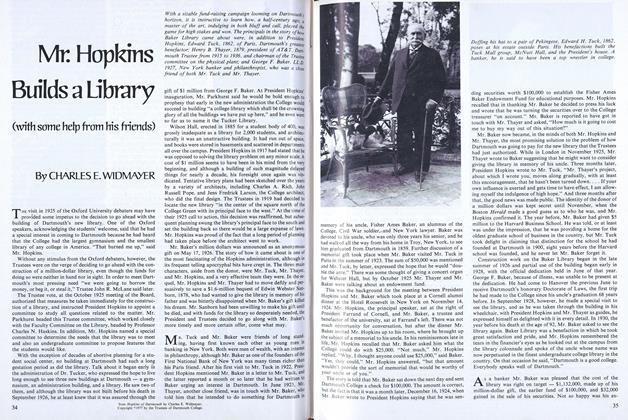

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19