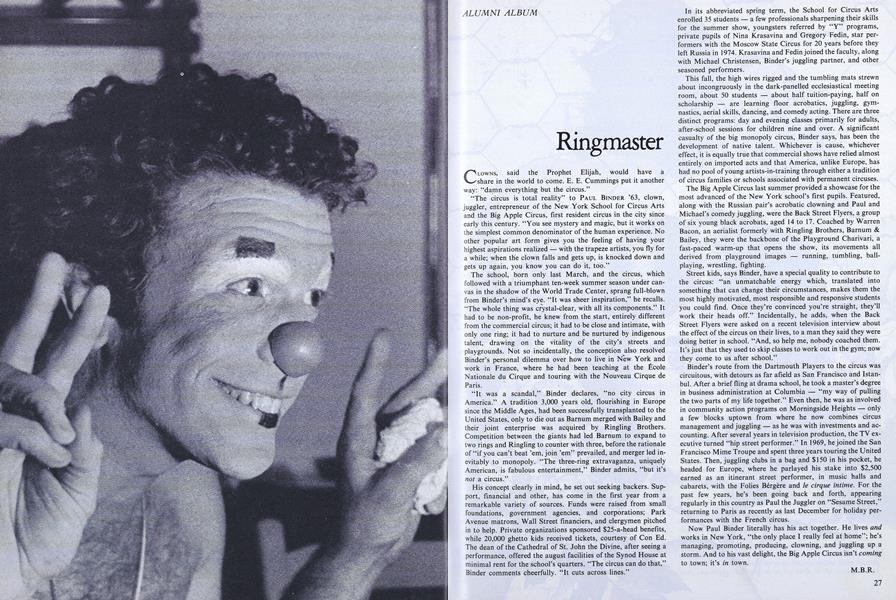

Clowns, said the Prophet Elijah, would have a share in the world to come. E. E. Cummings put it another way: “damn everything but the circus.”

“The circus is total reality” to Paul Binder ’63, clown, juggler, entrepreneur of the New York School for Circus Arts and the Big Apple Circus, first resident circus in the city since early this century. “You see mystery and magic, but it works oh the simplest common denominator of the human experience. No other popular art form gives you the feeling of having your highest aspirations realized with the trapeze artists, you fly for a while; when the clown falls and gets up, is knocked down and gets up again, you know you can do it, too.”

The school, born only last March, and the circus, which followed with a triumphant ten-week summer season under can- vas in the shadow of the World Trade Center, sprang full-blown from Binder’s mind’s eye. “It was sheer inspiration,” he recalls.

“The whole thing was crystal-dear, with all its components.” It had to be non-profit, he knew from the start, entirely different from the commercial circus; it had to be dose and intimate, with only one ring; it had to nurture and he nurtured by indigenous talent, drawing on the vitality of the city’s streets and playgrounds. Not so incidentally, the conception also resolved Binder’s personal dilemma over how to live in New York and work in France, where he had been teaching at the Ecole Nationale du Cirque and touring with the Nouveau Cirque de Paris.

“It was a scandal,” Binder declares, “no city circus in America.” A tradition 3,000 years old, flourishing in Europe since the Middle Ages, had been successfully transplanted to the United States, only to die out as Bafnum merged with Bailey and their joint enterprise was acquired by Ringling Brothers. Competition between the giants had led Barnum to expand to two rings and Ringling to counter with three, before the rationale of “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” prevailed, and merger led in- evitably to monopoly. “The three-ring extravaganza, uniquely American, is fabulous entertainment,” Binder admits, “but it’s not a circus.”

His concept clearly in mind, he set out seeking backers. Sup- port, financial and other, has come in the first year from a remarkable variety of sources. Funds were raised from small foundations, government agencies, and corporations; Park Avenue matrons, Wall Street financiers, and clergymen pitched in to help. Private organizations sponsored $25-a-head benefits, while 20,000 ghetto kids received tickets, courtesy of Con Ed. The dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, after seeing a performance, offered the august facilities of the Synod House at minimal rent for the school’s quarters. “The circus can do that,” Binder comments cheerfully. “It cuts across lines.”

In its abbreviated spring term, the School for Circus Arts enrolled 35 students a few professionals sharpening their skills for the summer show, youngsters referred by “Y” programs, private pupils of Nina Krasavina and Gregory Fedin, star per- formers with the Moscow State Circus for 20 years before they left Russia in 1974. Krasavina and Fedin joined the faculty, along with Michael Christensen, Binder’s juggling partner, and other seasoned performers.

This fall, the high wires rigged and the tumbling mats strewn about incongruously in the dark-panelled ecclesiastical meeting room, about 50 students about half tuition-paying, half on scholarship are learning floor acrobatics, juggling, gym- nastics, aerial skills, dancing, and comedy acting. There are three distinct programs: day and evening classes primarily for adults, after-school sessions for children nine and over. A significant casualty of the big monopoly circus, Binder says, has been the development of native talent. Whichever is cause, whichever effect, it is equally true that commercial shows have relied almost entirely on imported acts and that America, unlike Europe, has had no pool of young artists-in-training through either a tradition of circus families or schools associated with permanent circuses.

The Big Apple Circus last summer provided a showcase for the most advanced of the New York school’s first pupils. Featured, along with the Russian pair’s acrobatic clowning and Paul and Michael’s comedy juggling, were the Back Street Flyers, a group of six young black acrobats, aged 14 to 17. Coached by Warren Bacon, an aerialist formerly with Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey, they were the backbone of the Playground Charivari, a fast-paced warm-up that opens the show, its movements all derived from playground images running, tumbling, ball- playing, wrestling, fighting.

Street kids, says Binder, have a special quality to contribute to the circus: “an unmatchable energy which, translated into something that can change their circumstances, makes them the most highly motivated, most responsible and responsive students you could find. Once they’re convinced you’re straight, they’ll work their heads off.” Incidentally, he adds, when the Back Street Flyers were asked on a recent television interview about the effect of the circus on their lives, to a man they said they were doing better in school. “And, so help me, nobody coached them. It’s just that they used to skip classes to work out in the gym; now they come to us after school.”

Binder’s route from the Dartmouth Players to the circus was circuitous, with detours as far afield as San Francisco and Istan- bul. After a brief fling at drama school, he took a master’s degree in business administration at Columbia “my way of pulling the two parts of my life together.” Even then, he was as involved in community action programs on Morningside Heights only a few blocks uptown from where he now combines circus management and juggling as he was with investments and ac- counting. After several years in television production, the TV ex- ecutive turned “hip street performer.” In 1969, he joined the San Francisco Mime Troupe and spent three years touring the United States. Then, juggling clubs in a bag and SISO in his pocket, he headed for Europe, where he parlayed his stake into $2,500 earned as an itinerant street performer, in music halls and cabarets, with the Folies Bergere and le cirque intime. For the past few years, he’s been going back and forth, appearing regularly in this country as Paul the Juggler on “Sesame Street,” returning to Paris as recently as last December for holiday per- formances with the French circus.

Now Paul Binder literally has his act together. He lives and works in New York, “the only place I really feel at home”; he’s managing, promoting, producing, clowning, and juggling up a storm. And to his vast delight, the Big Apple Circus isn’t coming to town; it’s in town.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

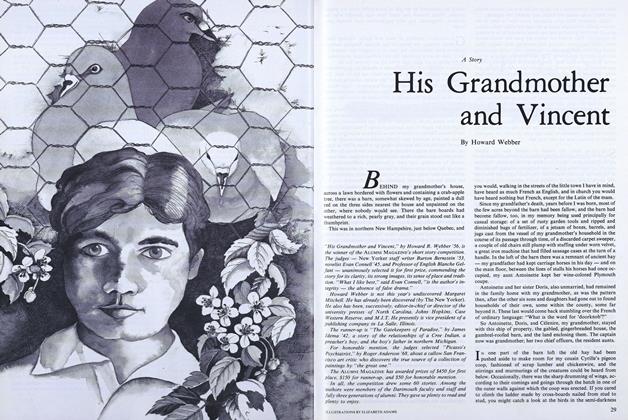

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

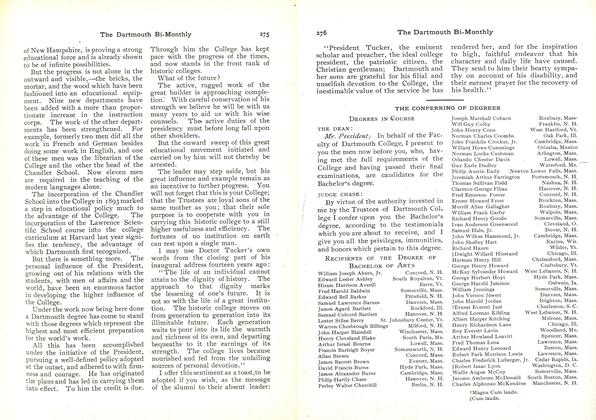

ArticleRECIPIENTS OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS

AUGUST, 1907 -

Article

ArticleCANOE CLUB TRIP

August 1921 -

Article

ArticleStudent Leaders of College Year Nearing Close

June 1947 -

Article

ArticleFive Newly Elected Members Of Dartmouth Alumni Council

June 1950 -

Article

ArticleHotchkiss '50 Named Associate College Dean

July 1958 -

Article

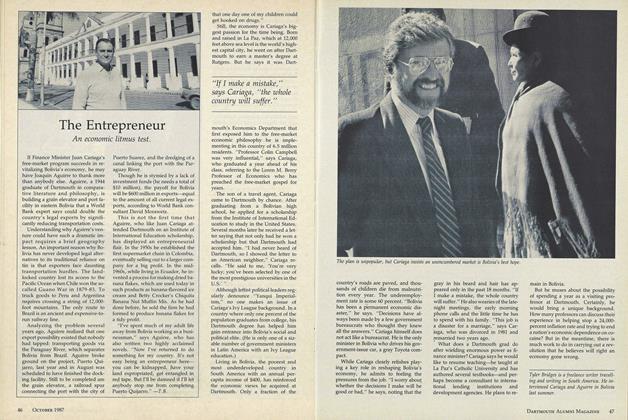

ArticleThe Entrepreneur

OCTOBER • 1987