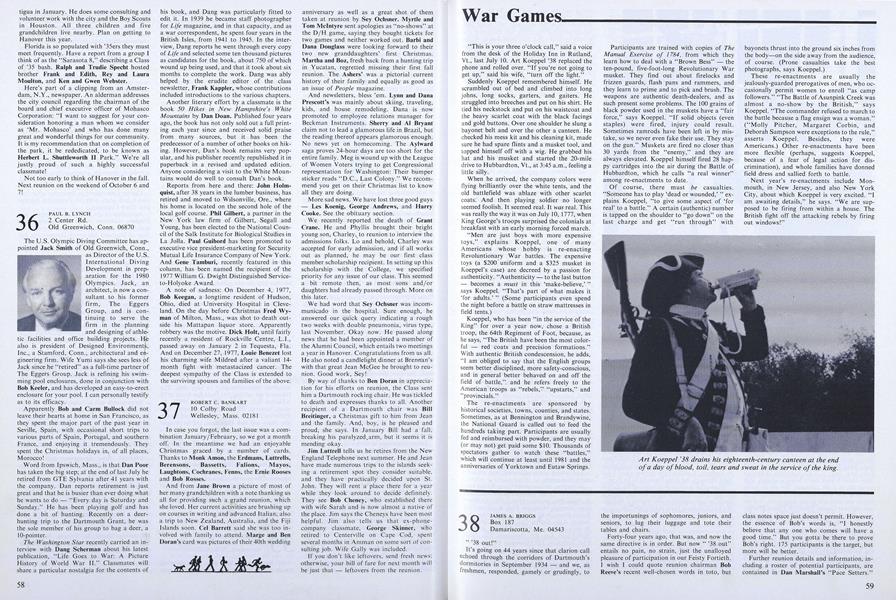

"This is your three o'clock call," said a voice from the desk of the Holiday Inn in Rutland, Vt., last July 10. Art Koeppel '38 replaced the phone and rolled over. "If you're not going to get up," said his wife, "turn off the light."

Suddenly Koeppel remembered himself. He scrambled out of bed and climbed into long Johns, long socks, garters, and gaiters. He struggled into breeches and put on his shirt. He tied his neckstock and put on his waistcoat and the heavy scarlet coat with the black facings and gold buttons. Over one shoulder he slung a bayonet belt and over the other a canteen. He checked his mess kit and his cleaning kit, made sure he had spare flints and a musket tool, and topped himself off with a wig. He grabbed his hat and his musket and started the 20-mile drive to Hubbardton, Vt., at 3:45 a.m., feeling a little silly.

When he arrived, the company colors were flying brilliantly over the white tents, and the old battlefield was ablaze with other scarlet coats. And then playing soldier no longer seemed foolish. It seemed real. It was real. This was really the way it was on July 10, 1777, when King George's troops surprised the colonials at breakfast with an early morning forced march.

"Men are just boys with more expensive toys," explains Koeppel, one of many Americans whose hobby is re-enacting Revoluntionary War battles. The expensive toys (a $200 uniform and a $325 musket in Koeppel's case) are decreed by a passion for authenticity. "Authenticity — to the last button — becomes a must in this 'make-believe,' " says Koeppel. "That's part of what makes it 'for adults.' " (Some participants even spend the night before a battle on straw mattresses in field tents.)

Koeppel, who has been "in the service of the King" for over a year now,- chose, a British troop, the 64th Regiment of Foot, because, as he says, "The British have been the most colorful — red coats and precision formations." With authentic British condescension, he adds, "I am obliged to say that the English groups seem better disciplined, more safety-conscious, and in general better behaved on and off the field of battle,", and he refers freely to the American troops as "rebels," "upstarts," and "provincials."

The re-enactments are sponsored by historical societies, towns, counties, and states. Sometimes, as at Bennington and Brandywine, the National Guard is called out to feed the hundreds taking part. Participants are usually fed and reimbursed with powder, and they may (or may not) get paid some $10. Thousands of spectators gather to watch these "battles," which will continue at least until 1981 and the anniversaries of Yorktown and Eutaw Springs.

Participants are trained with copies of TheManual Exercise of 1784. from which they learn how to deal with a "Brown Bess" — the ten-pound, five-foot-long Revolutionary War musket. They find out about firelocks and frizzen guards, flash pans and rammers, and they learn to prime and to pick and brush. The weapons are authentic death-dealers, and as such present some problems. The 100 grains of black powder used in the muskets have a "fair force," says Koeppel. "If solid objects (even staples) were fired, injury could result. Sometimes ramrods have been left in by mistake, so we never even fake their use. They stay on the gun." Muskets are fired no closer than 30 yards from the "enemy," and they are always elevated. Koeppel himself fired 28 happy cartridges into the air during the Battle of Hubbardton, which he calls "a real winner" among re-enactments to date.

Of course, there must be casualties. "Someone has to play 'dead or wounded,' " explains Koeppel, "to give some aspect of 'for real' to a battle." A certain (authentic) number is tapped on the shoulder to "go down" on the last charge and get "run through" with bayonets thrust into the ground six inches from the body—on the side away from the audience, of course. (Prone casualties take the best photographs, says Koeppel.)

These re-enactments are usually the jealously-guarded prerogatives of men, who occasionally permit women to enroll "as camp followers." "The Battle of Asunpink Creek was almost a no-show by the British," says Koeppel. "The commander refused to march to the battle because a flag ensign was a woman." ("Molly Pitcher, Margaret Corbin, and Deborah Sampson were exceptions to the rule," asserts Koeppel. Besides, they were Americans.) Other re-enactments have been more flexible (perhaps, suggests Koeppel, because of a fear of legal action for discrimination), and whole families have donned field dress and sallied forth to battle.

Next year's re-enactments include Monmouth, in New Jersey, and also New York City, about which Koeppel is very excited. "I am awaiting details," he says. "We are supposed to be firing from within a house. The British fight off the attacking rebels by firing out windows!"

Art Koeppel '38 drains his eighteenth-century canteen at the endof a day of blood, toil, tears and sweat in the service of the king.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMR. TUCK GIVES BUILDING TO HISTORICAL SOCIETY

January, 1912 -

Article

Article"THE DARTMOUTH" CHANGES COMPETITIONS

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MARCH 1963 -

Article

ArticleHiking for Dollars

OCTOBER 1997 By Jim Keating '93 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

January 1950 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

November 1935 By Warde Wilkins '13