SOME time ago, reading that an inventor had succeeded in walking across the Hudson River on special shoes of his own devising, I was reminded of a letter that John Ledyard wrote from Paris to his cousin Isaac Ledyard in Connecticut, in April 1786, reporting that he had observed with interest a Frenchman's attempt to cross the Seine using "a new invented method of walking upon the water."

"But the trial failed," he wrote. "The man walked not half over the river before the things on which he floated turned him heels over head and he was taken up by the Boat."

In 1786, John Ledyard had beep two years in Europe trying to arrange a voyage around the world, partly for commercial reasons he wanted to open up fur trading between the civilized world and the northwest coast of America and partly because he craved travel. Ledyard had already completed several remarkable trips by the time he lazed along the Seine that spring day when he was 35. His canoe trip down the Connecticut River when he left Dartmouth in 1773 is well known, but that was only a beginning. Six years later, as a corporal in the Royal Marines, Ledyard stood in the Pacific surf by the side of Captain James Cook on the morning when Cook, trying to get his men off a Hawaiian beach after a quarrel with the islanders, was stabbed and killed by a chief. On that same expedition Ledyard first saw fur-rich Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island and first visited Russian territory Alaska and Kamchatka. The next few years would take him back to England, home to America, to Europe again, through Russia to Siberia, back to England, and finally to Egypt, where he died at the outset of what might have been his greatest trip.

Dartmouth still breeds good travelers, but travel is far easier now than in Ledyard's century. It is difficult for us today to comprehend the strength of Ledyard's wanderlust and determination, which not only impelled him to seek exotic places but got him to his goals or as close as a man could possibly get. Some of these places remained exotic for a long time after Ledyard. Even a century later, when Phileas Fogg and Passepartout were making their way around the world (in 1872, says Verne), they gave no thought at all to a route through Siberia; nor could they have completed their trip in 80 days if they had gone that way, since the TransSiberian railway was finished only shortly before World War I. When Baedeker got out his first guide to Russia in 1914, he described the Trans-Sib, but Yakutsk, visited long before by Ledyard, lay far north of the railway and was still not a place that needed mention in the guidebook. Indeed, when my job took me to Yakutsk in 1963, few Americans or, for that matter, few Westerners had been there since Ledyard, and I wondered then if I might be the first alumnus of the College since John Ledyard to visit that distant, icy place.

MUCH of what we know about Ledyard we owe to Jared Sparks, a prolific biographer and a president of Harvard. Some of Sparks's biographic works are said to depart a little from the facts, but there is no reason to think that such was the case with his book on Ledyard. Sparks relied when he could on materials collected earlier by Ledyard's cousin Isaac, and on Ledyard's own journals. Even then, though, four decades after John Ledyard's death (the biography appeared in 1828), there were good-sized gaps in our knowledge of the man, gaps that no one has ever been able to fill.

We do know that he was born in Groton, Connecticut, in 1751, the son of a sea captain who died in the West Indies when John was still a boy. According to Sparks, his grandfather, who had come here from England and who was also a John Ledyard, was a close friend of Eleazar Wheelock. That relationship caused young Ledyard to enroll in the new college in 1772, two years after Wheelock had established himself in Hanover. The upper Connecticut region was still mainly wild country, although the days of Rogers' Rangers and Indian raids were over. Many of the remaining Indians in the area were in the process of moving west away from the white men, into the country of the Six Nations. Historian Jeremy Belknap, who visited Hanover at that time, reported that there were already several good buildings there, "which gives the place the appearance of a village." But beyond lay deep forest.

Ledyard had spent only four months in the little college when, Sparks tells us, he suddenly disappeared, without any notice to his comrades and without permission from Wheelock. He was gone from August until November, and he seems to have spent the time wandering up near Canada and westward into what is now Vermont and perhaps New York visiting the Six Nations. As a boy, Ledyard had been interested in the few Mohegans still living in Connecticut (one of his never-finished projects was to write "the story of Ben Un-cas"), and his trip to the Six Nations seems to have impressed him deeply. Years later, in the journal he kept in Siberia, he was ever comparing Yakuts and Mohegans, wigwams and yurts. It was this then-unique experience among both the aborigines of America and those of Asia that led him to report to Thomas Jefferson in 1788 that "I am satisfied myself that America was peopled from Asia." But it took a hundred more years and a Czech-American anthropologist named Ales Hrdlicka before that view was finally accepted.

One suspects that the only reason Ledyard returned to Hanover from the woods in late 1772 was the oncoming winter, a sufficient reason for a traveler, even a daring one, in upper New England without assurance of shelter. He did try out one night in the woods near Hanover later that winter, leading some fellow students up to Velvet Rocks where they camped out on pine boughs in the snow. One likes to think that they camped on the same ledge looking south to Mt. Ascutney where students of this century have also gone to get away from the campus for a bit. Like one such student, Ledyard and his friends found the night colder than anticipated, and came back to the College before dawn, well in time for morning prayers. When the next spring came Ledyard had had enough of college and, as every Dartmouth student knows, he built himself a crude dugout canoe and paddled down the Connecticut to his home. The river was still wild, it had its share of falls and rapids, and Ledyard told Jefferson years later that he had been so engrossed in reading Ovid that he and the canoe nearly got swept over Bellows Falls.

After Ledyard got home to Groton, he thought of studying in some local institution to become a Connecticut clergyman. Nothing came of that it appears that Eleazar Wheelock would not give him a recommendation and after a few weeks Ledyard, like many New Englanders before and after him, shipped out to sea. His father had been a captain; John for the moment was an able seaman. Next year he was home again, after a voyage which had taken him to the West Indies and North Africa and during which he had narrowly avoided a very different turn in life. When his ship had called at Gibraltar, Ledyard had disappeared; after some hours the captain discovered that Ledyard had enlisted as a British soldier on the Rock. What thoughts ran in his head we will never know. In any case, the captain got him back, and the voyage continued.

Ledyard seems to have thought, if briefly, of a bourgeois life when he came home again to Connecticut from the sea. It seems a woman was involved. A decade later, midway from Hawaii to Yakutia, he wrote wryly to his cousin Isaac that "Nature intended me for the tranquil scenes of domestic life; for ease and contemplation; and a thousand other fine soft matters that I have thought nothing about since I was in Love with R.E. of Stonington. What Fate intends further I leave to Fate but it is very certain that there has ever been a great difference, between the manner of life I have actually led and that which I should have chosen. ..."

In early 1775, Ledyard took to the sea again, for England. The first Continental Congress had met the previous September; war was not far off. Whether Ledyard could see a war coming is not clear but, in any case, he evidently went to England not to flee a revolution but because he had been done out of a share of his grandfather's in- heritance in Groton, and hoped that rich, though distant, relatives in England might help him get a start. Perhaps R.E. wouldn't have him without money. He was rebuffed by the relatives anyway, and so he went to sea with Captain Cook and spent the first four years of the Revolution, the years of Lexington and Valley Forge, out in the far Pacific.

THIS was Cook's third voyage to the Pacific, and this time his main task was to seek the Northwest Passage. It was to be a voyage of science as well as discovery, though, and Cook had on board his two ships Resolution and Discovery an astronomer, a botanist, a naturalist, and the artist John Webber who has given us our earliest view of Indians of the Northwest Coast. Ledyard began the voyage as a plain marine but soon attracted the attention of the great explorer- captain, who, like Ledyard, had begun his career as an able seaman. The young American was soon promoted to corporal and perhaps later to sergeant, sufficient rank that he could write later of his feelings "as officer and man." More important, Ledyard came in time to act as the expedition anthropologist (though not in name, since no such profession then existed), and on two occasions Cook assigned him to lead explorations of the interior of islands Unalaska, where he encountered his first Russians, and Hawaii, where he aimed to climb Mauna Loa but was forced to turn back by thick undergrowth after reaching within several miles of the peak.

Once in the Pacific, the expedition called at New Zealand, Tonga, and Tahiti, all of which Cook had visited before, then sailed north and discovered Hawaii. From Hawaii they went on to the coast of America at 42 degrees north (the Oregon- California state line) and sailed up the coast, rounding Alaska, penetrating the Bering Strait, and reaching several hundred miles into Arctic seas without finding the dreamed-of passage to the Atlantic. They returned to winter in Hawaii, and had a pleasant enough arrival. The expedition reached Kealakekua Bay in January 1779 when the Hawaiians were busy at their annual commemoration of the disappearance of the god Lono. Whether or not the Hawaiians thought Cook was Lono, they certainly saw some link, and the two ships were met by canoes bearing an enthusiastic crowd that Ledyard estimated at 15,000 people.

Like many visitors, the Englishmen overstayed their welcome. They began after some days to quarrel with the Hawaiians, who would seem to have decided rather soon that whoever had sent these fair strangers, it was not Lono. Unfortunately, after the ships finally sailed away they were driven back to Kealakekua by a gale that splintered one of Resolution's masts. Ledyard wrote later that "our return was as disagreeable to us as it was to the inhabitants. ... It was evident that our former friendship was at an end, and that we had best hasten our departure to some different island where our vices were not known, and where our extrinsic virtues might gain us another short space of being wondered at, and doing as we pleased. ..." Before that could happen the Hawaiians stole the Discovery's cutter, Cook and Ledyard and a squad of marines went on shore to take the native king hostage until the cutter should be returned, and the quarrel broke out that led to Cook's death.

It would be another year and a half before Discovery and Resolution came home to Deptford, sailing first under Discovery's captain Charles Clerke and then, after Clerke died at sea of tuber- culosis, under the command of Cook's first lieutenant, John Gore, a native of Virginia. During that time they saw more of Russia's Pacific dominions, and China, but no more of Polynesia. What they had seen, however, had started Ledyard thinking on the problem of Polynesian migration. He had made a glossary of Maori words while in New Zealand, and later found such a close similarity between Maori and Hawaiian that he decided that a great Polynesian migration across the Pacific must have occurred within the last thousand years. The question was, Where had they started from? If one looked at the linguistic evidence, and at the pattern of places where the breadfruit grew, he would guess at an Asian origin. And yet, he wrote, if one considered wind patterns and Hawaii's distance from Asia, it seemed probable that the natives of Hawaii had arrived "from the Eastward which is America." As in the case of Ledyard's theory of American Indian origins in Asia, it took a long time and Heyerdahl to go much beyond this.

Ledyard got back to England in 1780 to find the war continuing between England and his own country. Sparks claims that Ledyard, still in the Royal Marines, refused to go fight his fellow-countrymen; at a guess, his ex-Virginian commander John Gore may have helped him in this. He finally came home, the fighting over, at the end of 1782 and spent four months in Hart- ford writing his account of Cook's last voyage, which seems to have sold well when it was published in 1783.

Ledyard was already thinking about a new adventure, a commercial one this time: the opening of fur trade with the Pacific. In 1778, at Nootka Sound, Cook's men had bought from the Indians a quantity of beaver, sea otter, and wolverine furs to make themselves warm clothing as they sailed north. Later, stopping along the China coast on their way westward after Cook's death, they found to their surprise that a beaver fur bought for a sixpence brought the equivalent of a hundred dollars. This happy find had a profound effect both on Ledyard and, somewhat later, on American history.

Washington Irving wrote in Astoria, in 1836, that "the rich peltries of the north" were one of the two main objects of commercial gain that had led to daring enter- prise in our hemisphere's history gold being the other. Ledyard dared, but failed, in the fur enterprise: failed in repeated attempts after he returned to America to find a way to finance a fur-seeking expedi- tion by ship to the North Pacific; failed subsequently to complete his famous journey across Siberia to the Pacific, where he planned somehow to cross over to Northwest America and then, first pf all civilized men, cross our continent from west to east, marking the path for knew trade route. But this was a great and even triumphant failure, though John Ledyard did not live to see the triumph. Stephen Watrous, who published Ledyard's Siberian journal and letters in 1966, has made clear (as Washington Irving unfor- tunately had not) the close connection, through Thomas Jefferson, between Ledyard's plans and voyages and the subsequent opening of the Northwest fur trade, symbolized by the founding of Astoria on the Columbia River in 1811.

WHAT has interested most writers and readers about Ledyard is his trip overland from Europe to Siberia and back. In September 1787, three months and 5,000 miles out of Moscow, Ledyard reached Yakutsk on the Lena River, just 500 miles short of the Pacific coast. On arrival he was told by the commandant of Yakutsk that it was too late in the season to continue his trip eastward. It was true that there were six inches of snow already on the ground, and the temperature was dropping fast. (Yakutsk is very near the northern cold pole, and temperatures of over 90 degrees below zero Fahrenheit have been recorded. The townspeople put up double storm windows three thicknesses of glass in winter. A traveler today flies from Yakutsk to Moscow in May and thinks Moscow looks lush and green in contrast.) But Ledyard was not afraid of cold. The previous winter, to get from Stockholm to St. Petersburg, he had walked around the northern end of the Gulf of Bothnia 1,200 miles on foot in sub- arctic temperatures and he protested to the Yakutsk commandant that he wanted to go on to Okhotsk, on the Pacific coast. It was no use.

The commandant's refusal seems caused not by concern over Ledyard getting frost- bite but by direct orders from St. Petersburg to let him go no farther. parently, the commandant did not object when Ledyard, faced with this refusal, retreated south from Yakutsk to spend the winter in Irkutsk, a larger and more civilized place. He thought he could look forward to good company in Irkutsk; when he had passed through there earlier he had made the acquaintance of Karamyshev, the director of the Irkutsk bank, a cultured man who had studied botany under Linnaeus in Uppsala. Almost as soon as Ledyard arrived back in Irkutsk, however, he was arrested and then sent back under guard to European Russia, a tough six- week winter journey. He was finally pushed over the western border of the Russian Empire into Poland in March 1788, with a warning that he could expect to be hanged if he ever returned. Why all this was done, Ledyard was never told. He did learn that his explusion had been ordered by the empress herself, Catherine the Great; he guessed that her motives were "a mixture of jealousy, envy and malice."

Jefferson, who as American minister in Paris had supported Ledyard's Siberian trip strongly, later surmised that the initial permission for Ledyard to take his trip had been given without Catherine's knowledge, and that when she learned he was on his way to the Pacific she ordered him stopped. When Ledyard passed through St. Petersburg and Moscow on his way eastward, Catherine was away on her famous long trip to the Ukraine and Crimea during which Potemkin showed her his sham villages. We also know from the diary of Catherine's secretary that later, when Ledyard had reached Siberia, she personally ordered his return.

But why? Modern writers have surmised that Catherine's main motive was fear that Ledyard's journey, and the new trade route he was planning, could in the end weaken Russia's hold on the North Pacific. Perhaps, in the end, it did. If Ledyard helped to open the Northwest fur trade, it is not too much to say that he helped us gain Alaska. (There was even a time, some decades after Catherine II, when it seemed we might gain more than Alaska in those regions; not in territory, perhaps, but at least commercially. Before the trans- Atlantic cable was laid successfully in 1866, Americans including the elder George Kennan had been working for several years in the Yukon, Alaska, and Siberia to complete an overland telegraph linking America and Europe via Siberia. That project was put to an end by the trans-Atlantic cable, but later, at the end of the century, E. H. Harriman thought long and hard about a Northwest Passage Railway that would have extended the Union Pacific system northwest to Bering Strait. A car ferry to bridge the strait, a line southwest to link up with the Trans- Siberian, and New York to Paris by Pullman sleeping-car would have become a reality. If it had, Russian-American relations might have turned out far differently; just how, one can only speculate.)

As for the question of Catherine and Ledyard, it bears noting that Ledyard told an English acquaintance in Irkutsk after his arrest that he had been "taken up as a French spy." Modern writers have made little of this. Yet Ledyard was known to be associated with the Marquis de Lafayette, who had written to the French ambassador in Russia on Ledyard's behalf; Lafayette had come back from the American Revolution to push for reform in France, where revolution was fast approaching. The once- liberal Catherine, who had been filled with disgust and horror by America's assertion of independence, can hardly have welcomed the idea of a Yankee friend of Lafayette penetrating her empire, for whatever reason.

There has grown up somewhere the legend of an affair between Catherine and Ledyard. It is true that Catherine, of whom a British ambassador had written two decades earlier that "her face and figure are greatly altered for the worse since her accession," was still having passionate episodes with men at the time Ledyard visited Russia, when she was almost 60. Still, it seems most unlikely that she ever even saw Ledyard. She was, as noted, away in the south when he began his trip to Siberia, and there is no reason to suspect a meeting of the two while he was being rushed under guard from Siberia westward to the Polish border. Indeed, if they had met it would hardly have been a time of romance. When Ledyard was brought before a Russian general at Mogilev just before being pushed into Poland, the general told him that his sovereign was amiable and prudent, adding, however, that sovereigns did have long arms. Ledyard says he replied: "Yes by God Mr. le General yours are very long Eastward; If your Sovereign should stretch the other Westward she would never bring it back again entire, and I myself would contend to lob it off."

Although Ledyard had no affair with Catherine, it may be that, as Ledyard's pbiographer Helen Augur suggests, when he the woman he had been seeking, a woman to make him whole again." The evidence is fragmentary. It amounts to little more than an intriguing note in his journal that he left Vilna in company with"the distressed Girl of Dantzig." Augur suggests that she was Jewish, which could explain the reference in a letter Ledyard wrote to Cousin Isaac from London, to having had "a few days rest among the beautiful daughters of Israel in Poland." In any case, if there was an affair of the heart it must have been brief and it may well have been his last.

Poor John Ledyard was perhaps momentarily disheartened and was cer tainly penniless when he reached London in May 1788 after his Russian adventures. His spirits soon revived, and he wrote to his mother in America: "I have trampled the world under my feet, laughed at fear, and derided danger. Through millions of fierce savages, over parching deserts, the freezing north, the everlasting ice, and stormy seas, have I passed without harm. How good is God!"

ONLY two months after reaching London, Ledyard set off again, with the backing of a scientific patron, Sir Joseph Banks, on his next and last—journey, to Africa. He wrote to Jefferson that he aimed "to see what he can do with that continent." In fact, his purpose was to discover the source of the River Niger and chart its course, then totally unknown. His plans, says Sanche de Gramont in his book on the Niger, were "preposterous." He determined to go first to Cairo, then to Mecca although he had no knowledge of Arabic and almost no experience in the Muslim world and then, crossing over to what is now Sudan, he was to make his way westward to the Niger. This presumably seemed logical at the time, since it was believed that the Niger rose near the sources of the Nile and flowed west to the Atlantic. After reaching Cairo, however, Ledyard changed his plans. He wrote Jefferson that "from Cairo I am to travel southwest about 300 leagues to a black king. Then my present conductors will leave me to my fate. Beyond, I suppose I shall go alone. ..."

He never did; Cairo was the end of the long road he had embarked on 15 years before, when he pushed off downstream from the Hanover shore. Ledyard died in Cairo, after he had come down with a stomach complaint and dosed himself successively with vitriolic (sulfuric) acid and then tartar emetic. He was not yet 38.

Had he lived, I like to think that he would have found the Niger, although it would have taken a 2,000-mile journey across Africa, with few west-running streams to encourage him. Perhaps he would have avoided, or survived, the yellow fever and malaria that felled so many Niger-seekers. Then, perhaps, he would have gone home and married R. E. of Stonington. Perhaps he would have even ended as a rich man, like some Ledyards of the next century. Then again, perhaps John Ledyard would have kept on traveling. Jefferson told friends later that after the Niger, Ledyard had planned to go to Ken- tucky and then "endeavor to penetrate westwardly to the South Sea."

So far as known, no portrait of John Ledyard survives, but we can see him through the description of a friend: "He was above the middle stature; not tall nor corpulent; athletic, firm, and robust; with light eyes and hair, aquiline nose, broad shoulders, and full chest." He was no Burton in Arabia, no fanatic; just a brave Yankee, full of dreams and energy. Much fuller than most of us; and although his dreams failed him, they came true for America, in the decades after his tragically early death.

John Ledyard

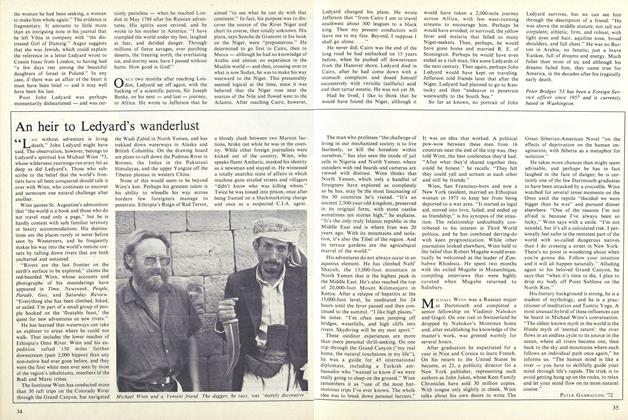

Map hy Erwin Raisz. reprinted from Passage to Glory by Helen Augur, Doubleday, 1946

Map hy Erwin Raisz. reprinted from Passage to Glory by Helen Augur, Doubleday, 1946

Peter Bridges '53 has been a Foreign Service officer since 1957 and is currentlybased in Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

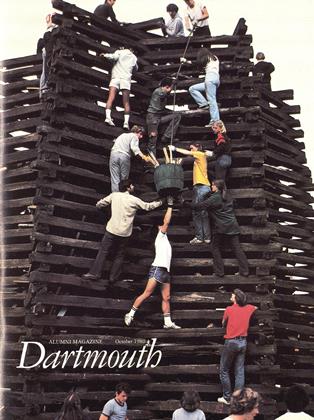

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleAn Heir to Ledyard's Wanderlust

October 1980 By Peter Gambaccini '72

Features

-

Feature

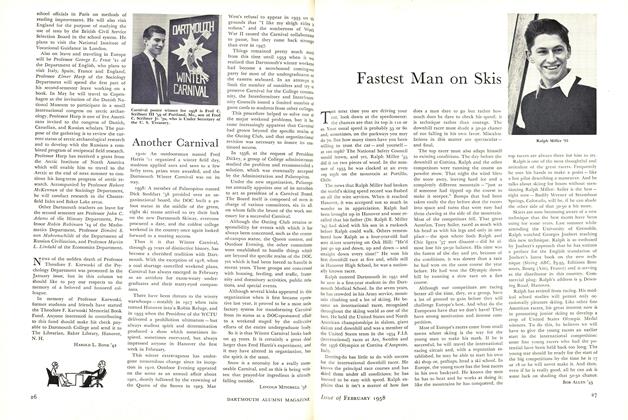

FeatureFastest Man on Skis

February 1958 By BOB ALLEN '45 -

Feature

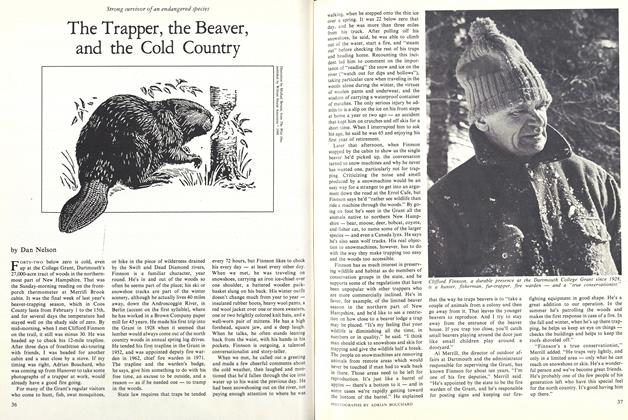

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

JUNE 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Feature

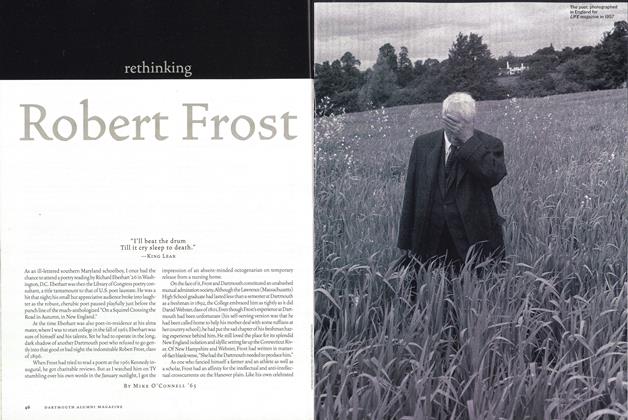

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

Nov/Dec 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

FeatureWelcome to the dark places

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Rob Eshman