Early this year, in these pages, we presented a sketchy outline of an impressive document, a long detailed report produced over a year and a half of arduous labor by a committee of 14 - ten faculty members, the provost, the dean of the College, and two students - charged by the faculty with a monumental task: "to undertake a complete review of the academic program in conjunction with year-round education and to make recommendations to the faculty for enhancing the quality of the Dartmouth educational experience."

In all 73 pages of recommendations and elucidation of the philosophy behind them, the most sweeping change, advocated by the slenderest of margins, was a proposal that the College abandon the four-quarter academic calendar in favor of three trimesters, two of 14 weeks each followed by a 12-week summer term. While affirming their commitment to year-round education, the committee sought through the medium of longer terms to reduce the fragmentation they saw as the greatest weakness of the current Dartmouth Plan. Their goal: to protect the best of both worlds, to retain the flexibility of yearround operation while adopting the comparatively unhurried pace of almost traditional semester-length terms.

The report called also for more sharply defined course requirements, increased emphasis on writing skills, greater continuity in student residence, and easing of the pressure imposed on faculty members by the Dartmouth Plan. A series of special faculty meetings was scheduled through winter and spring terms to discuss - and reject or approve - particulars of the report, in preparation for a subsequent recommendation by the full faculty of arts and sciences to the trustees.

At early spring meetings, the faculty turned down, by a vote of 81 -111, the committee's own half-hearted - by a one-vote margin - proposal to replace quarters with trimesters, as well as a separate recommendation offered by faculty members on the Committee on the Quality of Student Life that would have had the College revert to a traditional fall-winter-spring academic calendar.

Other recommendations in the report of the Committee on the Curriculum and Year-Round Education fared little better at the hands of the full faculty. By June, only six specific points had received unequivocal approval: one delineating the three divisions of humanities, sciences, and social sciences as basic units for distributive requirements; a declaration that courses in the major should not count for distributions; another that consideration be given to a program introducing freshmen to the nature of the liberal arts and their responsibilities under an elective system; a proposal that departments review teaching and other obligations to insure that assignments be equitably shared by all faculty members; and another that would have divisional councils look into methods of evaluating teaching.

Nine sections - six to do with curriculum and three with calendar - were accepted after amendment; one substitute was approved; four were passed over as no longer pertinent; four were rejected outright; one was postponed; and 12, including two substitutes and an amendment, were committed to the standing Committee on Instruction. The proposal that the trustees establish a sabbatical-leave policy to provide a term off after every six terms of teaching was changed to read "after every five terms." An amendment to the effect that faculty would not normally teach more than four courses per year was added.

The Committee on Instruction has been dealing this fall with some of the issues referred to it by the faculty and has duly returned some recommendations. One was that a proposal for a five-day reading period at the end of each term, added following defeat of the trimester plan, be modified to provide for only a two-day hiatus between the end of classes and the start of examinations. At a sparsely attended meeting, the faculty sent the issue back to its own executive committee, after President Kemeny declined to break a 39-39 tie. Impeccable sources deny a report in The Dartmouth that one professor argued seriously that two days would make too short a reading period but three too long. but there seems to have been a lot of profound discussion as to whether or not a scheduled reading period would encroach on academic freedom by "legislating" teaching style.

Dismay was allegedly registered over the differential between 12.6 reading days and 36.5 "thinking" days in the average Ivy League institution and the total absence of reading days and the minimal six "thinking" days in which Dartmouth indulges itself.

Sic transit dialectica.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

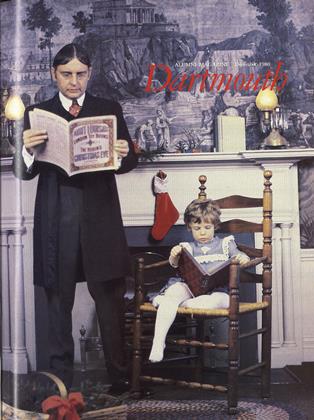

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

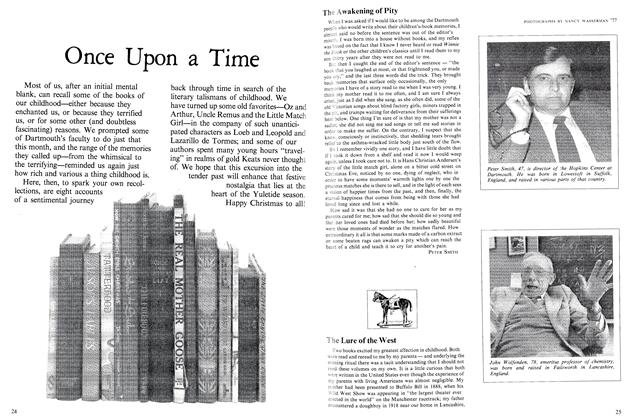

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY ROOM,

December, 1911 -

Article

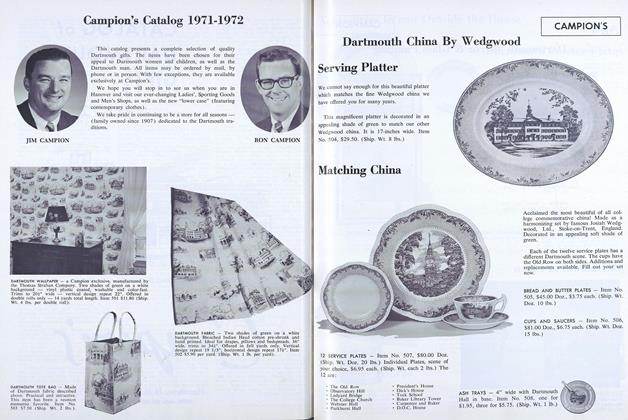

ArticleCampion's Catalog 1971-1972

OCTOBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleUnder-standing Polymers

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE REMINISCENCES*

August, 1914 By J.K. LORD -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1971 By JOHN H. MARSHALL '71 -

Article

ArticleVirtual Munchausen

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott