EVAPERONby Nicholas Fraserand Professor Marysa NavarroNorton, 1981. 192 pp. $14.95

The play Evita has thrust upon us the image of a beautiful, manipulative, and eagerly powerful woman from the fascinating period of the 1940s in Argentina. EvaPeron, a timely and artfully crafted biography, helps us understand the details of her contradictory life and agonizing death. The problem of finding the truth about Evita and, more generally, about Argentina during the Peronist period is a daunting task. The pervasiveness of myth and counter-myth, like a maze of distorting mirrors, lays traps for biographers which the careful research of Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro skillfully avoids. The myths of Peronism are powerful and, long after the deaths of Evita and of Peron, still raise strong populist sentiment in Argentina.

On the one hand, Peron and Evita themselves promoted a self-serving myth of a dynamic couple, fiercely in love with each other and with their people the descamisados (literally "shirtless ones") of the lower classes. This myth envisions the couple as wresting power from the selfaggrandizing, effete "oligarchy" and bringing far-reaching social justice labor codes, social security, pensions, hospitals, and housing to the poor. Evita is cast as a dynamo who, almost saint-like, devoted herself to the poor, working through the night personally dispensing charity from her huge Eva Peron Foundation and during the day assisting in labor-union organizing.

As Fraser and Navarro show, this Peronist myth was met by a counter-myth, another set of distorting mirrors. First the oligarchy and then the many people who suffered under the dictatorial tactics of Peron - including earlier followers in the army and the unions found passionate reasons to characterize Peron as a simple imitator of European fascists. In their myth Evita became simply the provincial bastard daughter clawing her way to power by using first her body and her meager theatrical abilities and later her fiery speeches and personalized charity to achieve her manipulative ends.

Even today in Argentina there is little middle ground between myth and countermyth, and it is to the credit of Fraser and Navarro that they have thoroughly researched the existing literature and added to it many new personal interviews to construct a new vision of a more human, loving couple with foolish, often childish, Contradictory desires and habits. The Perons enjoyed the unusual combination of spontaneous support of the masses and early postwar prosperity with which they could then dispense favors to their followers without taking from the rich. Evita's is the tale of a beautiful, glamorous, but not particularly graceful woman whose early motivation was to marry the man she had grown to love. It was only later that she turned her efforts toward maintaining him in power. If her goal was manipulative, as the anti-Peronist myth would have it, she accomplished it, the authors argue, through her personal devotion to assisting the poor.

Fraser and Navarro lay aside two further misconceptions. One, also a part of the Peronist myth, suggests that Evita whipped up the mass support that first brought Peron to the presidency in October 1945. To the contrary, the flood of lower-class supporters whose history-setting appearance in Buenos Aires brought Peron to power, the authors demonstrate, was spontaneous, the result of Peron's own earlier support for the unions. Only after Peron became president did Evita establish contact with union leaders and later still, with her charity work, gain the passionate loyalty of the poor. The second misconception of more recent vintage is that Evita was a feminist. True, Evita was perceived as a powerful leader an untraditional role for women and she did found a woman's movement of sorts - the Peronist Women's Party but Fraser and Navarro show that though she no doubt had a strong personal following, she acted always to turn that following to support Peron. Her movement and her own political ambition were devoted totally to the man she loved, General Juan Peron.

The one weakness of the book is its insufficient development of the broader context of Argentinian politics. As Fraser and Navarro argue, after October 1945 "Evita and Peron became different people. In a political context they ceased simply to be characters and became representatives of the forces that had altered politics. . . . " These "forces" are briefly sketched but, even in a book addressed to the general public, they need more depth so the reader can understand the potency of populism. One would like to see more attention paid to the intricate economic changes, social programs, and union activities which shaped the period. The reader gets little sense of the point of view of the descamisados, and one wishes that some oral-history interviews from this class had been included. The account of Evita's union activities is also skimpy (in stark contrast to the long account of her charity work). Most surprising, one finds only scanty quotations from her "violent" and "messianic" speeches which could give life to the bond between her and her people. But these are only minor omissions; the general points are all very well made. .

A well-written book filled with revealing personal details of this contradictory political leader, Eva Peron makes exciting reading that brings us closer to a human understanding of a woman clouded by myth.

THOMAS BOSSERT

Thomas Bossert, Latin America specialistand visiting professor of government, was inArgentina when Peron returned to power in1973. Having been literally caught in thecrossfire between rival Peronist gangs, headmits to "a healthy respect for the powerof myth."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

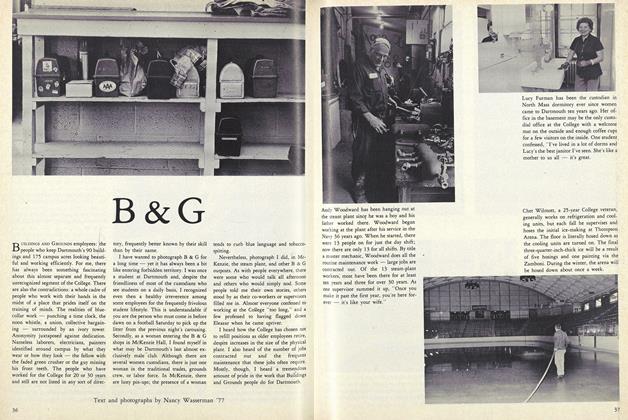

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn

Robert H. Ross '38

-

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFundaments

June 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksGalaxies

November 1979 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksUp From the Nickelodeon

NOVEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksPassable

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Way You Talk

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

MAY 1965 -

Books

BooksPIRATES PURCHASE

JANUARY 1932 By E. P. K. -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN CAMPAIGNS OF ROCHAMBEAU'S ARMY 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783. Vol. 1. THE JOURNALS OF CLERMONT-CREVECOEUR, VERGER, AND BERTHIER. Vol. 2. ITINERARIES AND MAPS AND VIEWS.

MARCH 1973 By Louis Morton -

Books

BooksDecorous Image

November 1982 By P. D. S. -

Books

BooksCHRETIEN DE TROYES: INVENTOR OF THE MODERN NOVEL.

March 1958 By WILLIAM R. LANSBERG '38 -

Books

BooksTHOMAS CRAWFORD: AMERICAN SCULPTOR.

OCTOBER 1964 By WINSLOW B. EAVES