"Like Abraham of old," the citation read, "you ventured forth from your native land to go to a strange country impelled by the love of God, your desire to teach His Torah, and the need to be of service to His people,"

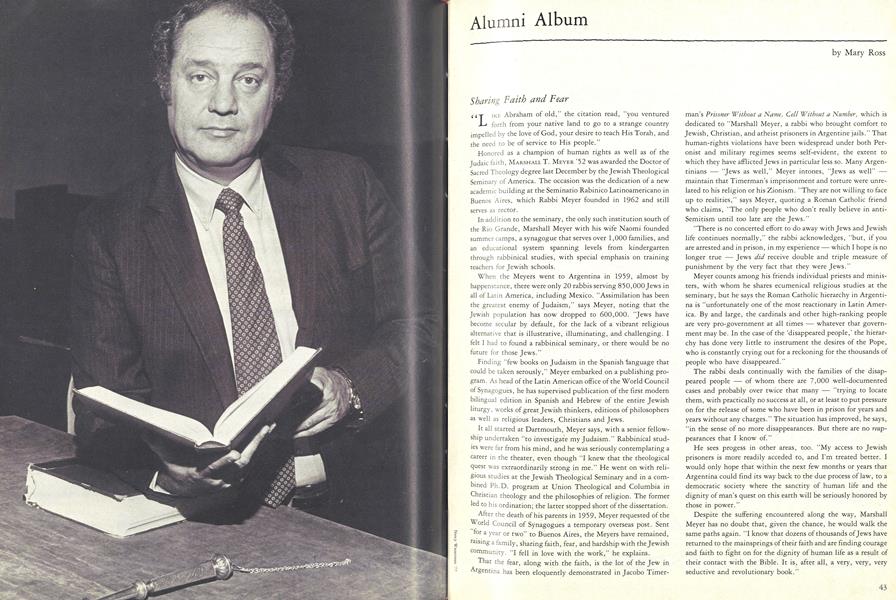

Honored as a champion of human rights as well as of the Judaic faith, MARSHALL T. MEYER '52 was awarded the Doctor of Sacred Theology degree last December by the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. The occasion was the dedication of a new academic building at the Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires, which Rabbi Meyer founded in 1962 and still serves as rector.

In addition to the seminary, the only such institution south of the Rio Grande, Marshall Meyer with his wife Naomi founded summer camps, a synagogue that serves over 1,000 families, and an educational system spanning levels from kindergarten through rabbinical studies, with special emphasis on training teachers for Jewish schools.

When the Meyers went to Argentina in 1959, almost by happenstance, there were only 20 rabbis serving 850,000 Jews in all of Latin America, including Mexico. "Assimilation has been the greatest enemy of Judaism," says Meyer, noting that the Jewish population has now dropped to 600,000. 'Jews have become secular by default, for the lack of a vibrant religious alternative that is illustrative, illuminating, and challenging. I felt I had to found a rabbinical seminary, or there would be no future for those Jews."

Finding "few books on Judaism in the Spanish language that could be taken serously," Meyer embarked on a publishing program. As head of the Latin American office of the World Council of Synagogues, he has supervised publication of the first modern bilingual edition in Spanish and Hebrew of the entire Jewish liturgy, works of great Jewish thinkers, editions of philosophers as well as religious leaders, Christians and Jews.

It all started at Dartmouth, Meyer says, with a senior fellowship undertaken "to investigate my Judaism." Rabbinical studies were far from his mind, and he was seriously contemplating a career in the theater, even though "I knew that the theological quest was extraordinarily strong in me." He went on with religious studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary and in a combined Ph.D. program at Union Theological and Columbia in Christian theology and the philosophies of religion. The former led to his ordination; the latter stopped short of the dissertation.

After the death of his parents in 1959, Meyer requested of the World Council of Synagogues a temporary overseas post. Sent for a year or two" to Buenos Aires, the Meyers have remained, raising a family, sharing faith, fear, and hardship with the Jewish community. "I fell in love with the work," he explains.

That the fear, along with the faith, is the lot of the Jew in Argentina has been eloquently demonstrated in Jacobo Timer man's Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, which is dedicated to "Marshall Meyer, a rabbi who brought comfort to Jewish, Christian, and atheist prisoners in Argentine jails." That human-rights violations have been widespread under both Peronist and military regimes seems self-evident, the extent to which they have afflicted Jews in particular less so. Many Argen- tinians ― "Jews as well," Meyer intones, "Jews as well" ― maintain that Timerman's imprisonment and torture were unrelated to his religion or his Zionism. "They are not willing to face up to realities," says Meyer, quoting a Roman Catholic friend who claims, "The only people who don't really believe in antiSemitism until too late are the Jews."

"There is no concerted effort to do away with Jews and Jewish life continues normally," the rabbi acknowledges, "but, if you are arrested and in prison, in my experience ― which I hope is no longer true ― Jews did receive double and triple measure of punishment by the very fact that they were Jews."

Meyer counts among his friends individual priests and ministers, with whom he shares ecumenical religious studies at the seminary, but he says the Roman Catholic hierarchy in Argentina is "unfortunately one of the most reactionary in Latin America. By and large, the cardinals and other high-ranking people are very pro-government at all times ― whatever that government may be. In the case of the 'disappeared people,' the hierarchy has done very little to instrument the desires of the Pope, who is constantly crying out for a reckoning for the thousands of people who have disappeared."

The rabbi deals continually with the families of the disappeared people ― of whom there are 7,000 well-documented cases and probably over twice that many ― "trying to locate them, with practically no success at all, or at least to put pressure on for the release of some who have been in prison for years and years without any charges." The situation has improved, he says, "in the sense of no more disappearances. But there are no reappearances that I know of."

He sees progess in other areas, too. "My access to Jewish prisoners is more readily acceded to, and I'm treated better. I would only hope that within the next few months or years that Argentina could find its way back to the due process of law, to a democratic society where the sanctity of human life and the dignity of man's quest on this earth will be seriously honored by those in power."

Despite the suffering encountered along the way, Marshall Meyer has no doubt that, given the chance, he would walk the same paths again. "I know that dozens of thousands of Jews have returned to the mainsprings of their faith and are finding courage and faith to fight on for the dignity of human life as a result of their contact with the Bible. It is, after all, a very, very, very seductive and revolutionary book."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

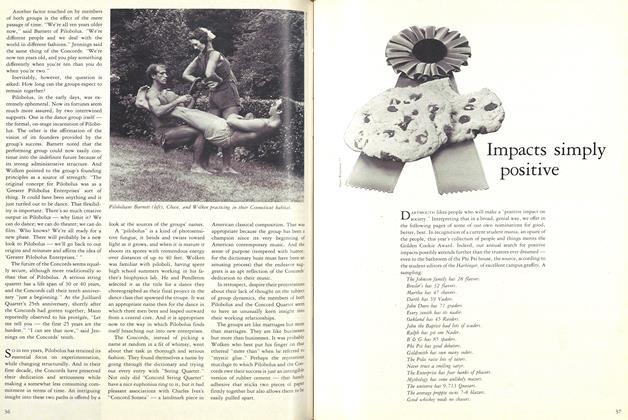

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureThe Nautical Nyes

MAY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

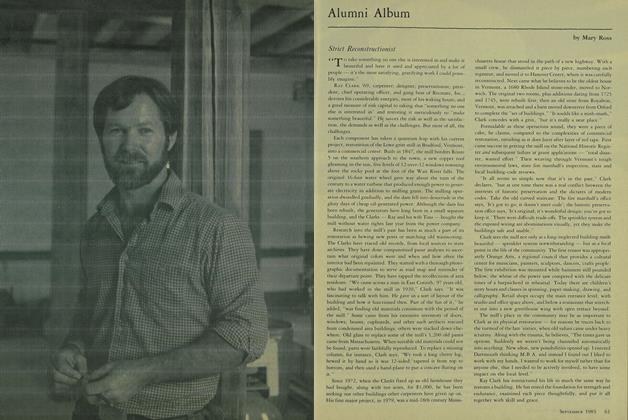

Article

ArticleStrict Reconstructionist

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE COST OF AN EDUCATION

February, 1914 -

Article

Article1946 Alumni Fund Rings Up $416,589

August 1946 -

Article

ArticleJohn Alden's Bible

January 1958 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February, 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1960 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M'27 -

Article

ArticleWestern Connecticut

OCTOBER 1962 By HOMER A. YATES JR. ’45