What's one of the Criticisms you heard about 'The Cosby Show' in its heyday?, asks assistant English professor Martin Favor, referring to the sitcom that shaped many Americans' impressions of black life. '"These are the whitest black people I've ever seen in my life.' Well, they don't look white to me. So white and black must mean something other than color. It means they're upper-middle-class professionals who live in this gorgeous brownstone filled with expensive art."

"The Cosby Show," which vaulted to the top of the Nielsen charts in the eighties, revived an old controversy in black art and politics: What does it mean to be "authentically" African American? According to Favor, for many black writers during the Harlem Renaissance the burst of proud black literature during the 1920s the answer was clear: the real "black folk" were southern, poor, rural African Americans. "There's a whole pattern of these black middle-class writers going to the South to get in touch with their blackness," says Favor, 29, who teaches a course on the Harlem Renaissance, also the subject of his recently completed first book.

The Harlem Renaissance, centered among writers and artists and musicians in the New York ghetto, grew out of black oppression after World War I. Most of the writers were college-educated; the country's economic prosperity gave them the freedom to write. They were children and grandchildren of African Americans who had migrated northward after the Civil War, and their pilgrimage to the rural South was a return to their roots.

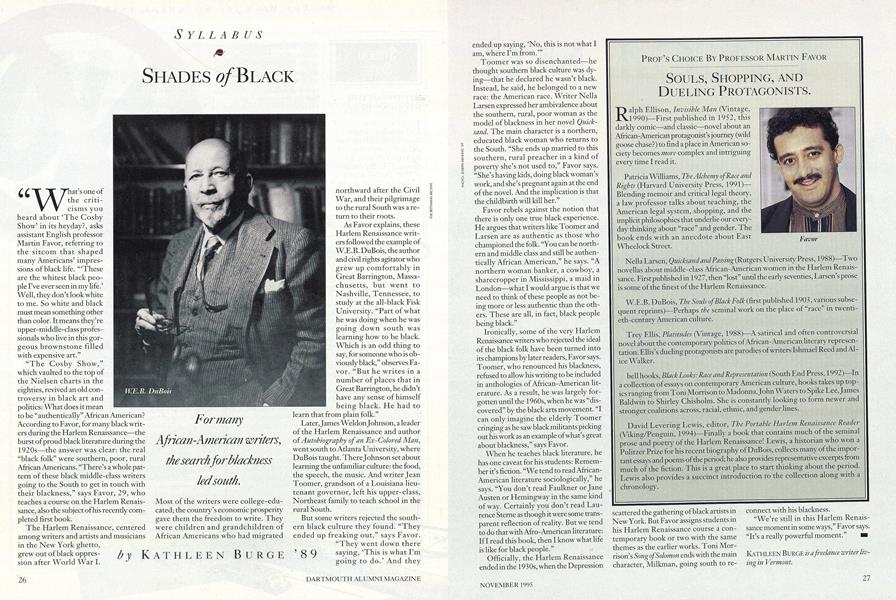

As Favor explains, these Harlem Renaissance writers followed the example of W.E.B. DuBois, the author and civil rights agitator who grew up comfortably in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, but went to Nashville, Tennessee, to study at the all-black Fisk University. "Part of what he was doing when he was going down south was learning how to be black. Which is an odd thing to say, for someone who is obviously black," observes Favor. "But he writes in a number of places that in Great Barrington, he didn't have any sense of himself being black. He had to learn that from plain folk."

Later, James Weldon Johnson, a leader of the Harlem Renaissance and author of Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, went south to Atlanta University, where DuBois taught. There Johnson set about learning the unfamiliar culture: the food, the speech, the music. And writer Jean Toomer, grandson of a Louisiana lieutenant governor, left his upper-class, Northeast family to teach school in the rural South.

But some writers rejected the southern black culture they found. "They ended up freaking out," says Favor. "They went down there saying, 'This is what I'm going to do.' And they ended up saying, 'No, this is not what I am, where I'm from.'"

Toomer was so disenchanted he thought southern black culture was dying that he declared he wasn't black. Instead, he said, he belonged to a new race: the American race. Writer Nella Larsen expressed her ambivalence about the southern, rural, poor woman as the model of blackness in her novel Quicksand. The main character is a northern, educated black woman who returns to the South. "She ends up married to this southern, rural preacher in a kind of poverty she's not used to," Favor says. "She's having kids, doing black woman's work, and she's pregnant again at the end of the novel. And the implication is that the childbirth will kill her."

Favor rebels against the notion that there is only one true black experience. He argues that writers like Toomer and Larsen are as authentic as those who championed the folk. "You can be northern and middle class and still be authentically African American," he says. "A northern woman banker, a cowboy, a sharecropper in Mississippi, a maid in London what I would argue is that we need to think of these people as not being more or less authentic than the others. These are all, in fact, black people being black."

Ironically, some of the very Harlem Renaissance writers who rejected the ideal of the black folk have been turned into its champions by later readers, Favor says. Toomer, who renounced his blackness, refused to allow his writing to be included in anthologies of African-American literature. As a result, he was largely forgotten until the 1960s, when he was "discovered" by the black arts movement. "I can only imagine the elderly Toomer cringing as he saw black militants picking out his work as an example of what's great about blackness," says Favor.

When he teaches black literature, he has one caveat for his students: Remember it's fiction. "We tend to read African-American literature sociologically," he says. "You don't read Faulkner or Jane Austen or Hemingway in the same kind of way. Certainly you don't read Laurence Sterne as though it were some transparent reflection of reality. But we tend to do that with Afro-American literature: If I read this book, then I know what life is like for black people."

Officially, the Harlem Renaissance ended in the 1930s, when the Depression scattered the gathering of black artists in New York. But Favor assigns students in his Harlem Renaissance course a contemporary book or two with the same themes as the earlier works. Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon ends with the main character, Milkman, going south to reconnect with his blackness.

"We're still in this Harlem Renaissance moment in some ways," Favor says. "It's a really powerful moment."

W.E.K. DnBop

For many African-American writers, the search for blackness led south.

KATHLEEN BURGE is a freelance writer living in Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

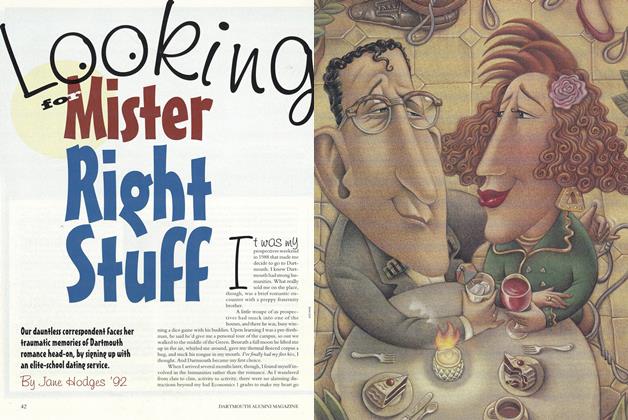

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

November 1995 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

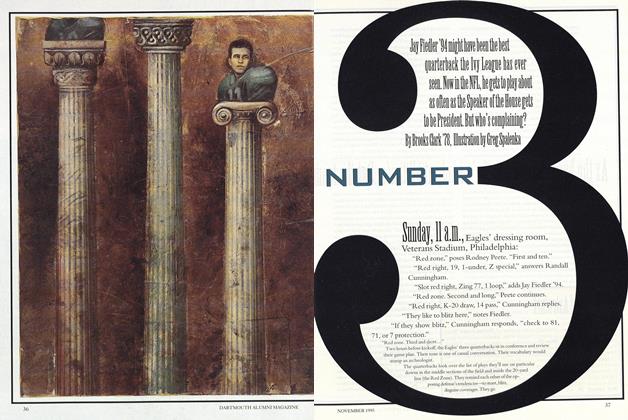

FeatureNUMBER 3

November 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

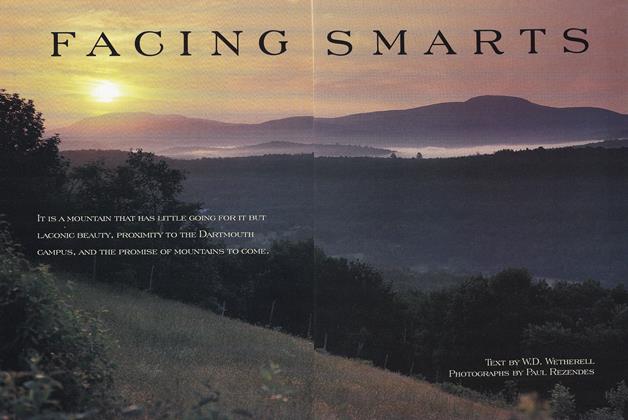

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

November 1995 By W.D.Wetherell -

Feature

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

November 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureSentimental Sap

November 1995 By Robert K. Nutt '49 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1995 By "E. Wheelock"

Kathleen Burge '89

-

Article

ArticleWhen Bad Things Happen

January 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleOne for the Road

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

NOVEMBER 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleMedieval Road Trips

JANUARY 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTales from Uncle Anton

JANUARY 1999 By Kathleen Burge '89