Memory block happens to nearly everyone, but Dr. Alexander Reeves of Dartmouth Medical School refutes the commonly held idea that it is an inevitable part of growing old

ELDERLY MAN: "DOC, I think I'm losing my memory."

DOCTOR: "HOW long have you had this problem?"

ELDERLY MAN: "What problem?"

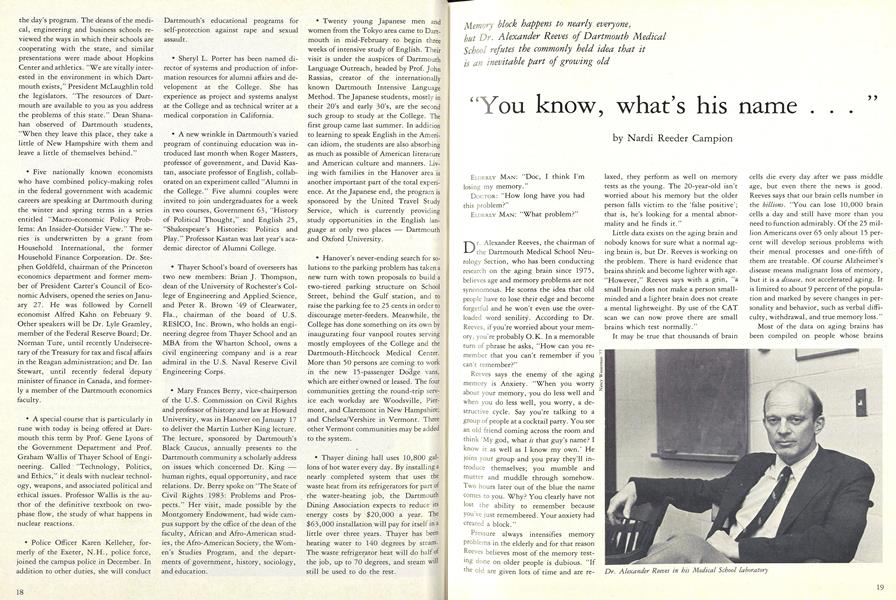

Dr. Alexander Reeves, the chairman of the Dartmouth Medical School Neurology Section, who has been conducting research on the aging brain since 1975, believes age and memory problems are not synonomous. He scorns the idea that old people have to lose their edge and become forgetful and he won't even use the overloaded word senility. According to Dr. Reeves, if you're worried about your memory, you're probably O.K. In a memorable turn of phrase he asks, "How can you remember that you can't remember if you can't remember?"

Reeves says the enemy of the aging memory is Anxiety. "When you worry about your memory, you do less well and when you do less well, you worry, a destructive cycle. Say you're talking to a group of people at a cocktail party. You see an old friend coming across the room and think 'My god, what is that guy's name? I know it as well as I know my own.' He joins your group and you pray they'll introduce themselves; you mumble and mutter and muddle through somehow. Two hours later out of the blue the name comes to you. Why? You clearly have not lost the ability to remember because you ve just remembered. Your anxiety had created a block."

Pressure always intensifies memory problems in the elderly and for that reason Reeves believes most of the memory testing done on older people is dubious. "If the old are given lots of time and are relaxed, they perform as well on memory tests as the young. The 20-year-old isn't worried about his memory but the older person falls victim to the 'false positive'; that is, he's looking for a mental abnormality and he finds it."

Little data exists on the aging brain and nobody knows for sure what a normal aging brain is, but Dr. Reeves is working on the problem. There is hard evidence that brains shrink and become lighter with age. "However," Reeves says with a grin, "a small brain does not make a person smallminded and a lighter brain does not create a mental lightweight. By use of the CAT scan we can now prove there are small brains which test normally."

It may be true that thousands of brain cells die every day after we pass middle age, but even there the news is good. Reeves says that our brain cells number in the billions. "You can lose 10,000 brain cells a day and still have more than you need to function admirably. Of the 25 million Americans over 65 only about 15 percent will develop serious problems with their mental processes and one-fifth of them are treatable. Of course Alzheimer's disease means malignant loss of memory, but it is a disease, not accelerated aging. It is limited to about 9 percent of the population and marked by severe changes in personality and behavior, such as verbal difficulty, withdrawal, and true memory loss."

Most of the data on aging brains has been compiled on people whose brains were affected by disease. Dr. Reeves and his co-investigator, Dr. Lawrence Jenkyn '72, were despairing of ever finding "normal" older people to study when Dr. John Woodhouse '21, former Dartmouth trustee (of whom Dr. Reeves says: "The only word I can think of for him is genius"), suggested they study the DuPont retirees who go in regularly for company-sponsored physical exams.

Woodhouse's idea proved a godsend. Doctors in Wilmington now administer to their 2,000 hale and hearty retirees a three-minute battery of tests designed by Reeves and Jenkyn. The test subjects are told three unrelated words; then after a period of distraction, they have to repeat them. They are asked to spell a five-letter word backward, and the doctors also test for regressive reflexes (certain physical reflexes that disappear as infants get older and reappear in some older people who are deteriorating mentally). The evidence so far confirms Reeves' belief that people maintain normal intelligence even up to age 95.

Meanwhile, back in the laboratory, Dr. Reeves and John Casteldo '76 are studying aging in rats. The rats are in two cages, ten. to a cage. One group is completely unstimulated. "Mentally," says Dr. Reeves, "those rats are sitting in rocking chairs." The other rats are given lots of handling and stimulation. Their cage is filled with climbing devices and they are taken out four times a week for an hour of treadmill exercise. Eventually Reeves will compare the branching of the nerve cells in the brains of all the rats to find out if the active rats have maintained their nerve cells better than the rocking chair rats.

Some increase in the nerve anatomy of stimulated rats has already been noted by others, which Dr. Reeves finds fascinating. "This would seem to indicate that just as bone strength is maintained by bone usage, and muscle strength by muscle usage, intellect can be preserved by usage. If you're a thinker, you'll probably keep on thinking, but if you retire to that mental rocking chair, you'll probably lose the ability to think. The mind can die in its boots if you want it to."

A physician who practices what he preaches, Alex Reeves is a 45-year-old egghead (in both senses of that word), a wiry athlete who talks fast, thinks fast, moves fast. He looks Ivy League, which is not surprising; he is a graduate of Lawrenceville School, Williams College, Cornell Medical School. He persuaded Cornell to admit him to medical school after three years of college, and he picked up his Williams degree ten years later. He grew up near Ridgewood, N.J., and married Anne Hay, the daughter of family friends, who used to come to his birthday parties. The Reeves have four children. Their two girls, both excellent skiers, are in Colorado College and Middlebury, while their two boys are still in school in Hanover.

Reeves burns up his high voltage energy at a rapid clip. Although he lives less than a mile from Mary Hitchcock Hospital, he rides his 10-speed bicycle to work via Lake Fairlee, a 40-mile trek that takes from 5 to 8 a.m. He and Richard Montague, owner of the Brick Store in Strafford, and Tom Officer '74 founded a club for serious cyclists called the Upper Valley Sporting Group. Some of the club's 30 members will race the U.V.S.G. orange-and-black jerseys in this year's Regionals (the New Hampshire and Vermont state bicycle meet).

A natural athlete, Reeves is also a topnotch cross-country skier and he was a star swimmer in college. He is a dedicated angler who ties his own flies and a devotee of Baroque music. A glance at Alexander Reeves' publications indicates he is a scholar as well. The list includes many mysterious titles such as Intracellular Response of Hippocampal Neurons in the Awake,Sitting Squirrel Monkey and Re-usable NylonSocket Holders for Use with Chronically FixedEmbedded Electrodes in the Cat.

As a physician he is admired by his patients. One of them told a questioner recently: "Unlike some doctors, Dr. Reeves is always available. All you have to do is call. He doesn't put people to bed; he expects them to keep going, and they do. But what I like best about him is he shoots no bull. He tells it like it is, straight out."

People pepper Dr. Reeves with questions about memory. Does the brain's memory bank operate like a computer? Where is data stored? How is it retrieved? What actually prevents us from dredging up a name or a fact?

"No," Alex Reeves tells them, "the brain is not like a computer. It is much, much more complex. We are only beginning to unravel its mysteries and we may have to wait until the next century to answer some of the most difficult questions about the biochemistry and anatomy of memory. We do know that one key to the problem of memory block is the fact that our brain uses the same circuits for emotionality and for learning. These two can block each other, making it impossible to learn or to retrieve information in certain emotionally charged situations."

A surprising number of people over 50 go to see Dr. Reeves because they believe they are losing their memories. "Older people are too sensitive about being forgetful," he says. "If a teenager loses her keys, she simply retraces her steps until she finds them. But if her grandmother loses her keys, she thinks that's a sign she's slipping; she panics and blocks her memory. The man who goes to the store, buys the newspaper but forgets to buy milk, probably doesn't have a problem. It's the man who forgets he needs the milk, or who forgets he even went to the store, who has a problem. The people I see who are in real difficulty are usually brought in by members of the family."

What can we do to preserve our memories? Dr. Reeves' prescription:

1) Relax. Memory responds to relaxation not stress. Don't worry if you're forgetful but do take advantage of all available aids to reinforce memory.

2) Keep up mental activities you enjoy. Reading is a marvelous mental exercise; television usually is not. Games and puzzles stimulate the mind; cocktail parties usually do not.

3) Do not smoke. Drink only moderately. Alcohol is a memory-killer. If drinking makes your memory black out, switch to ginger ale.

4) Be active in your community. Lots of social interaction challenges the mind and stimulation is vital.

5) Avoid sitting in a rocking chair and watching the world go by. The depressed and the isolated are more susceptible to illness than others.

6) Exercise regularly. What's good for the body is good for the mind - and vice versa. Always remember the mind/body war cry: "Use it or lose it!"

Dr. Reeves sometimes quotes Golda Meier: "It is no crime to be 70 years old, but it's no joke either." But, since he is a positive thinker, he would rather go with Robert Browning: "Grow old along with me/The best is yet to be."

Dr. Alexander Reeves in bis Medical School laboratory

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

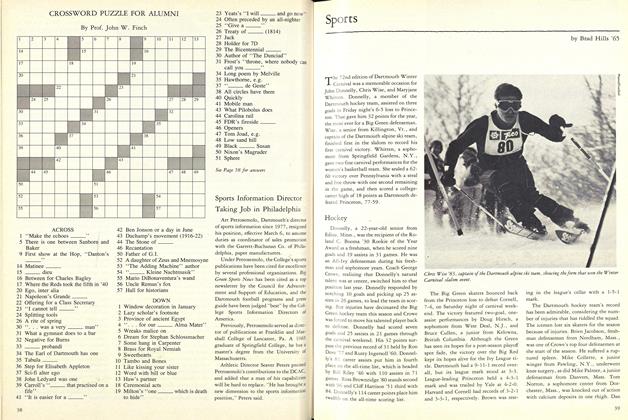

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticlePhilosopher Coach

March 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Nardi Reeder Campion

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to Editor

September 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1980 -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Cover Story

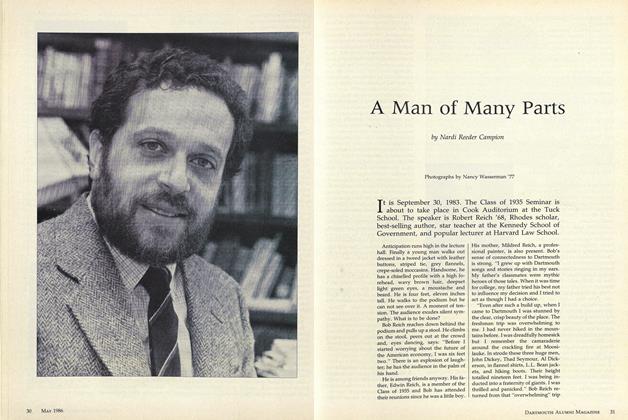

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleJody's PALS Sing Out

NOVEMBER 1999 By Nardi Reeder Campion

Features

-

Feature

Feature"The Real Business"

June 1955 -

Feature

FeatureSummary of Recommendations

APRIL 1959 -

Features

FeaturesCenter of Attention

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Feature

FeatureOpening Assembly

October 1951 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY