A great day at Christie's for Dartmouth as rare books sold at auction benefit Baker Library.

Outside, it is a lovely fall day just before Thanksgiving. Park Avenue has a crisp and busy sense about it, elegant beyond description: this is the way New York is supposed to look. Inside, up on the second floor of Christie's auction house, a bright, well-appointed chamber is made all the more exotic by lush tapestries dating from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and fine handcrafted mahogany chests etched with ornate designs. In the middle of the room, sit row after row of contemporary steel-framed chairs, artifacts of a century which has seen the triumph of function over form, of mass-production over more costly methods of manufacture. Yet the handful of people in the room are committed more to the past than to the 20th century, or so it would seem. Most are here to bid on books and manuscripts at an auction that will benefit the Library; some, your correspondent for one, will enter the bidding wars but briefly, withdrawing in mild panic lest a sneeze or an untoward itch cause the auctioneer to rap his small stonepiece to the desk with a brisk, "Sold ... to number 166."

In the room, people come and go, talking, not of Michelangelo, but of more mundane matters. The atmosphere is serious, reserved. It is a scholarly-looking group, a melange of dark suits, tweeds, and silk ties; an unusually large number of them wearing eyeglasses. Slight rustlings occur from time to time amidst a bank of red telephones to the auctioneer's left. In front of him is a spotter, who, probably more because of his manner than his dress, looks as if he just stepped out of a Dickens novel.

For all the genteel aura of the room, it is the auctioneer, one Stephen C. Massey, who is the center of attention, the main mover. The drama resides in the speed with which he solicits and announces the bids, moving the auction along. A slight, bearded man with a distincty British accent, Massey handles his audience skillfully, with just the right touch of humor, and ever so subtle an expression of exasperation that a particular lot is taking too long to reach its appropriate level. Later I learn that he is not merely the auctioneer, but the head man for Christie's New York division of books and manuscripts. Today he wears a three-piece suit with a bright green tie. (Not Dartmouth green, mind you. I wonder if he has chosen it by accident or on purpose.)

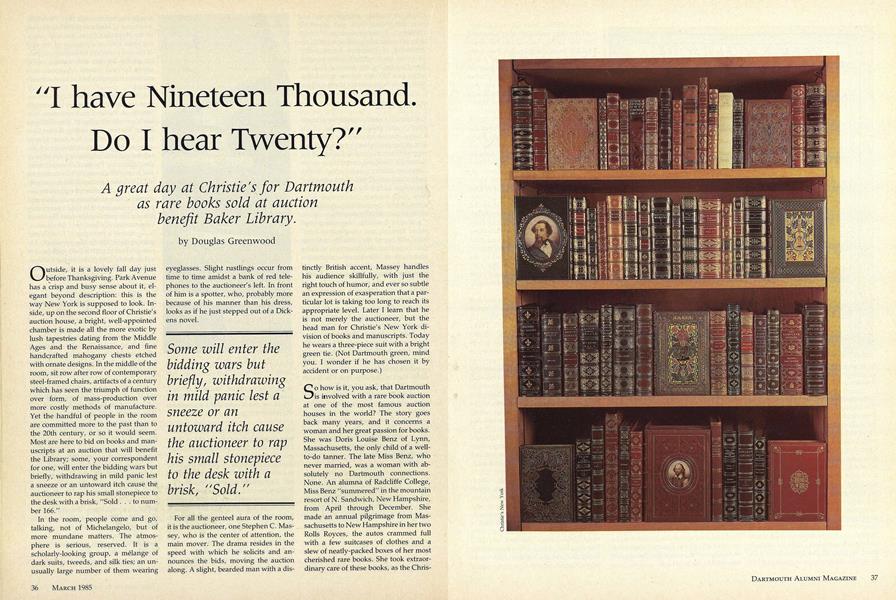

So how is it, you ask, that Dartmouth is involved with a rare book auction at one of the most famous auction houses in the world? The story goes back many years, and it concerns a woman and her great passion for books. She was Doris Louise Benz of Lynn, Massachusetts, the only child of a wellto-do tanner. The late Miss Benz, who never married, was a woman with absolutely no Dartmouth connections. None. An alumna of Radcliffe College, Miss Benz "summered" in the mountain resort of N. Sandwich, New Hampshire, from April through December. She made an annual pilgrimage from Massachusetts to New Hampshire in her two Rolls Royces, the autos crammed full with a few suitcases of clothes and a slew of neatly-packed boxes of her most cherished rare books. She took extraordinary care of these books, as the Chris tie's catalogue noted. "Rare books, and fine bindings in particular, have to be very carefully kept in a seaside environment. Thankfully, Miss Benz's house in Lynn was superbly built and her library, with its fitted, glazed mahogany bookcases, has preserved her collection in exactly the same condition as it was acquired." As her collection of books grew, she developed a taste for acquisition that was both well-informed and wide-ranging. Most serious collectors rely on the knowledge and outside assistance of experts; Miss Benz, according to her lawyer, relied largely on her own judgment and her increasing awareness of what was extraordinary and what was merely commonplace. Thus it came as a great surprise to the fraternity of rare book collectors when the quality of her collection was made known. As Christie's put it, "Miss Benz's library has been a buried treasure and we suspect that nobody present at this auction will have known of it."

The result of some 50 years of painstaking endeavor, her collection was, by the terms of her will, to be sold at auction. She wanted the proceeds to go to the best college library in New Hampshire, her adopted state. What makes the Benz story all the more remarkable is that there was no solicitation on the part of the College. And, as suggested above, bibliophiles got an added bonus, for Miss Benz also stipulated that the books be sold at auction, rather than be parceled out to one library, where they would be out of general circulation, and unavailable for purchase.

When officials from Christie's examined the Benz collection, they estimated that the College would realize about $500,000 from the sale. But they were "off" on both sides of the ledger. A first edition of John Keats's first book of poems inscribed by the author "to his friend G.F. Mathew," for example, was estimated to go at $25,000-35,000. It was a bargain at $lB,OOO. And the 1633 edition of George Herbert's The Temple-expected to go for a cool $7,000-10,000 sold for a mere $4,500. But for all the miscalculations that went that way, there were many more that went the other: a 9-volume set of Laurence Sterne's unforgettable The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, a Gentleman, estimated at $2,500-3,500 was bid up to nearly double at $6,000; the first edition of Shakespeare's collected Poems, thought to bring $15,000-20,000, closed at $29,000; while the Cresset Press printing of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Prog-ress fetched, at $22,000, more than three times the high end of its estimate (and this, over the telephone). Final figures are not yet in, but the first part of the Christie's sale alone netted $885,675, and two smaller offerings should push that figure over the million-dollar mark.

Dartmouth was well represented at the Christie's sale. Head librarian Margaret Otto was joined by Baker Library staffers Stan Brown '67, Philip Cronenwett, John James, and Phyllis Jaynes, all of whom were able to observe, but not participate in, the auction (standard procedure for parties privy to the "reserve" or minimum bids for selected items). Boston publisher David Godine '66, who studied rare books in England as a Senior Fellow, bid on a number of items, including two works by Edward V. Lucas, which he subsequently donated to the Dartmouth Archives.

In short, it was a bright day for Dartmouth, especially for the Library, since the proceeds are specifically earmarked for the purchase of rare books and manuscripts. I suspect Doris Benz might have been surprised at the large "take," but then, she obviously knew better than most what she was up to from the start. It reminded me of a comment I overheard at lunch, between sessions. One fellow turned to his companion, a wry, depressed look on his face, and said, "This is really hardball, isn't it?" The way book futures had been selling earlier that day at Christie's, one would have to agree.

Morton's work, "the first strictly historical ivork printed in America," was based on themanuscript of William Bradford, governor of Plymouth Colony. It sold for $8,500.Bradford, you will recall, sailed to America aboard the Mayflower.

Some will enter thebidding wars butbriefly, withdrawingin mild panic lest asneeze or anuntoward itch causethe auctioneer to raphis small stonepieceto the desk with abrisk, "Sold."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

March 1985 By Robert H. Conn

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Fall of '63

November 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBetween the Lines

DECEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Numbers Game

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Place of Art

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Family Affair

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

ArticleThe winter of our discontent

APRIL 1986 By Douglas Greenwood

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Friends' Best Friend

JANUARY 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySENIOR CANE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

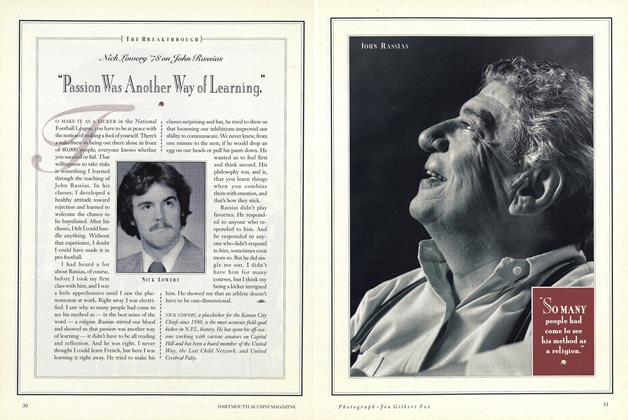

FeatureNick Lowery '78 John Rassias

NOVEMBER 1991 By John Rassias -

FEATURE

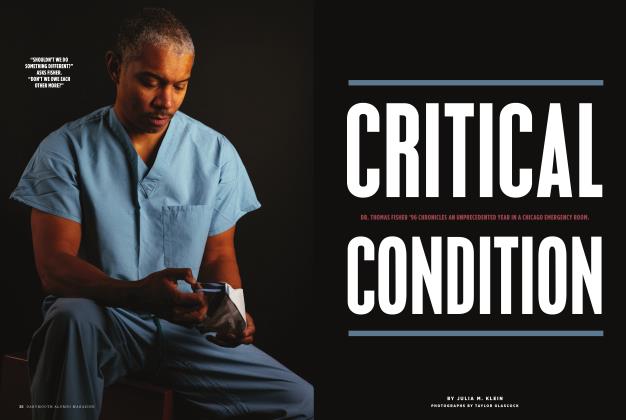

FEATURECritical Condition

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

FeatureTHREE POEMS

January 1958 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Feature

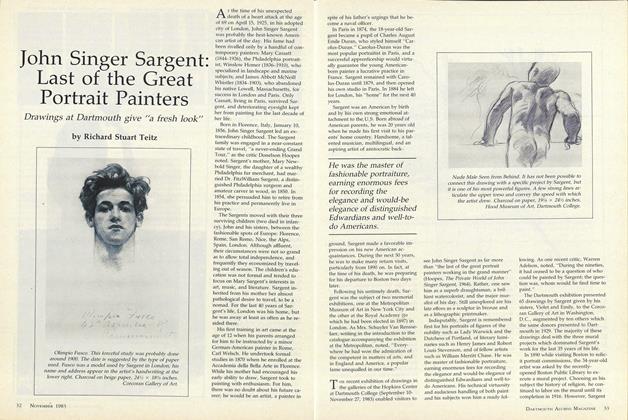

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz