In the search for the fortune-laden Atocha, a Dartmouth-bred archaeologist sought a scientific bonanza.

On September 4, 1622, a fleet of 28 Spanish vessels departed from Havana, Cuba, laden with New World plunder. Many of them never made it to Spain. Three and a half centuries after they left port, two of the ships were to change my life.

Much of the one and a half million pesos' worth of treasure a hoard worth today perhaps $400 millionwas assigned to the Santa Margarita and a new ship, the Nuestra Senora deAtocha. The Atocha had been built in the Havana shipyard and, sure to bring her good luck, was named for the most revered religious shrine in Spain. Just in case the Almighty's providence didn't extend to sinking enemy Dutch warships, the Atocha was fitted with 20 bronze canrtons. This strong ship was to sail last to protect the slow, lumbering merchant ships that followed in the rear.

But neither God's providence nor gunpowder could protect the ships from the weather.

On September 5, the fleets were overtaken by a rapidly moving hurricane. The wind hurled the fleet north toward the Florida reef line. At least four ships, including the Atocha and SantaMargarita, were swept headlong into the Florida Keys. Near a low-lying atoll fringed with mangroves, 15-foot rollers carried the Margarita across the reef, grounding her in the shallows beyond.

Meanwhile, with passengers huddled in prayer below deck, the Atocha approached the line of reefs dividing safe, deep water from certain death. The frenzied crew dropped anchors into the reef face, hoping to hold the groaning galleon off the jagged corai. A wave lifted the ship, and, in the next instant, flung it directly onto the reef,

The main mast snapped as the huge seas washed the Atocha off the reef. Water poured through a gaping hole in the bow, quickly filling the hull with water. The great ship slipped beneath the surface, finding bottom 55 feet below; only the stump of the mizzenmast broke the waves. Of the 265 persons aboard, 260 drowned. Three crewmen and two black slaves clung to the mast until they were rescued the next morning by a launch from a sister ship, the Santa Cruz.

The lost ships of the 1622 treasure fleet lay scattered over 50 miles stretching from the Dry Tortugas eastward to where the Atocha slipped beneath the water. About 550 people perished along with a total cargo worth more than 2 million pesos.

On June 15, 1973, I received a telegram sent from Key West by Mel Fisher, president of Treasure Salvors, Inc. For four years, Mel and his staff had been on the track of the two Spanish galleons. "I need an archaeologist," the telegram said. "I am sending you a round trip ticket."

I had no idea what that telegram was going to do to my life. Mel Fisher's quest was about to become one of the most lucrative and scientifically valuable treasure hunts of all time. But it had its costs. The hurricane that wrecked the Atocha was no more fierce than the forces spawned by Fisher's monomaniacal search. The effort took the lives of four people and consumed $8 million profits from Fisher's earlier salvage of a fleet of galleons sunk in 1715 plus the funds of hundreds of investors.

I was in Jamaica when the telegram reached me, and it took me completely by surprise. I had never met Mel Fisher, never been to Key West. I wasn't even a certified diver, much less a marine archaeologist. Since graduating from Dartmouth in 1960 with a degree in geology and a minor in anthropology, I had lived abroad first as a graduate student in Britain, then as a government archaeologist in Ghana, West Africa. In 1970, I moved to Jamaica to help excavate Spanish colonial land sites of the 16th and 17th centuries. Mel's researcher, Gene Lyon, had recommended me for the Atocha search. Several years before, Gene had given me some Spanish documents that helped me to interpret an archeological site I had been working.

As I read the telegram a second and third time, my head spun. My wife Marie and I had already decided to leave Jamaica in the next few months. However, we had no idea of where we would go or what we would do. After spending nearly 15 years working archaeological sites on land, I considered shipwreck archaeology the ultimate challenge. To me, the Atocha and the Margarita were the main characters of a first-rate mystery story.

It's as though Arthur Conan Doyle had set for Sherlock Holmes the task of solving a murder 350 years after the crime was committed. Holmes would face the same difficulties facing Mel: the eyewitnesses are dead. The scene of the crime has first to be located from incomplete records before it can be examined for clues. Scanty knowledge of the most trivial everyday affairs, such as where the sailmaker might have kept his tools, made every assumption, ]every theory, a stretch beyond known facts into the realm of thinly supported supposition.

Despite the fact that the Atocha had broken up and her artifacts were scattered and deteriorated, the 1622 galleon was still a fabulous archaeological site. Unlike sites on land, a shipwreck is an almost perfect snapshot of a given moment in history. Cities change over the years. Buildings are put up and torn down, and the character of an area's population changes. However, at the instant a ship goes down, it becomes a time capsule, entombing both the people on board and the tools and possessions that exemplify their way of life. Thus, shipwreck archaeology can fill in important details erased from dry-land sites by the passage of time.

The study of artifacts from the Atocha and the Margarita would help recreate the fascinating details of America's Spanish history one that began more than a century before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. The largest collection of Spanish artifacts in America is not to be found in museums but in the numerous shipwrecks that still lie undiscovered throughout the Caribbean Basin and along many of the southern shores of the United States.

The Atocha site was a way for me to prove that real archaeology could be done on a shallow-water wreck with as much certainty as a deep-water wreck or dry-land site. In 1973, there were very few professional archaeologists who believed that. In interpreting the meaning of artifacts, whether from a land site or a shipwreck, it's important to know the spatial relationship between the locations of various artifacts on the site. That's why careful measurements are taken before and during excavations, and why detailed site maps marking the locations of major finds are prepared. Some marine archaeologists and treasure hunters have argued that ships driven onto shallow shoals hit with such force that spatial relationships between artifacts on board are destroyed. I believed otherwise.

It was the archaeological challenge of a lifetime, and I couldn't simply walk away from it. Mel had found his archaeologist.

Based on information that Mel's crew had obtained from his work thus far, we suspected that the detached superstructure of the ship had been swept from deep water into the shallows and hit sand in the area of the Bank of Spain. The lower hull, beneath the turn of the bilge, should be relatively intact. Inside were 500 olive jars listed on the manifest, 80 or so tons of ballast, and, of course, the mother lode Mel Fisher's $400 million treasure.

For the next 12 years, Treasure Salvors fought the sea, the government, even modern-day pirates to recover this wealth. In their search they adapted every useful instrument of modern technology, following through with sweat in a dogged physical struggle with a capricious ocean. They were rewarded in spades.

On Wednesday, July 16, 1985, the Dauntless, tinder the direction of Mel's son Kane, uncovered a heavy concentration of artifacts near one of the anomalies picked up during a magnetometer survey. Soon, ingots, ballast, and thousands of silver coins were uncovered on the sea bed. When Mel called me from the wrecksite, he could hardly contain his excitement. "Kane has just found a whole bunch of treasure and ballast. How about that!" Mel exclaimed. "I think we've really found it this time."

New finds followed rapidly more coins, more copper ingots, more ballast but still no hull timbers or silver ingots that would indicate the mother lode. Suddenly, four days later, Kane's voice came over the radio. "Put away the charts. We found it!" Although Kane sounded calm and self-assured, I was certain that the scene aboard the Dauntless was total bedlam. Divers Andy Matroci and Greg Wareham had just swum into a mountain of silver ingots.

Almost immediately, everyone wanted to dive on the treasure. The water visibility wasn't good, and a thin layer of sand covered most of the main ballast pile. It was several days before the water was clear enough for us to see the entire site, but that didn't discourage the divers. What little they could see fed the flames of treasure fever. Swimming within arm's reach of $400 million can do that.

With the closing act of this great drama staring me in the face, I nearly choked with stage fright. There was only one Atocha in the whole universe. If we dismembered this wonderful time capsule without carefully recording all the artifacts, we would permanently destroy an extraordinary historical treasure.

When the weather broke several days later, I gave a lecture to the crew. "The whole world's watching us," I told them. "We've spent 16 years looking for the Atocha, and I don't want the whole site destroyed overnight. Other archaeologists are going to be particularly critical of our work. If you do the best job you possibly can, then, in the end, we'll have done a good job archaeologically."

I knew that everyone would rather be diving on the Atocha than listening to my speech about the historical significance of the mother lode. Over the past few years, some divers had gone out of their way to help me with the archaeology. Others didn't see my side of the story; they just wanted to find treasure. I had received excellent cooperation back in 1975, but now this was a different situation. I questioned whether the newer divers sitting in front of me understood anything I had said.

That afternoon, the salvage ships Dauntless, Swordfish, and Virgilona returned to the site and began digging on the mound. My crew of assistants and I had managed to lay a plastic grid that allowed us to measure the distances between artifacts. But in setting the boat anchors, the grid had been pulled off the ballast pile. It lay crumpled, off to one side. If we didn't start mapping the site immediately, we'd lose a lot of critical archaeological data.

There was mass confusion on the site. The ship captains seemed to be in a race, each vying to pull up treasure faster than the next guy. The whole project was out of control. Someone had to take charge of the operation before we destroyed the wrecksite.

To the delight of the reporters and photographers who crowded around, the Dauntless crew continued to bring up silver ingots. Meanwhile, Mike Rizzo, Jerry Cash and I laid the base line along the main axis of the site. Visibility was bad, and we weren't absolutely certain of the total extent of the site.

We were almost finished laying the line when Kane Fisher decided to blow with the mailboxes contraptions that use the boat's propwash to blast sand from the treasure. Within seconds an enormous sand storm enveloped us as we tried to keep our balance on the bottom. I looked over and saw Jerry and Mike holding onto the ballast pile while tying down the base line and adjusting the long tape measure that paralleled the line. I couldn't believe that Kane was digging near us. It was the worst thing he could be doing to this delicate mound of artifacts.

I was numb. So numb that all I could do was sit on the bottom of the ocean in a whirlwind of sand and cry. I wept thinking of all the time and energy I'd spent getting to this point the finding of the mother lode. I wept thinking of the promise I'd made to the press and to my professional colleagues that I was going to adhere to the highest archaeological standards.

What was going on now hardly represented the highest archaeological standards. The silver ingots rocked back and forth on top of the timbers as water churned around them violently. In a matter of minutes the blowers had disturbed the surface of the rock ballast and the precious silver ingots that were stacked on top of them. I felt I was watching my whole life evaporate in a cloud of sand.

I couldn't contain my anger any longer. I swam to the surface, climbed the ladder on the Dauntless, not even bothering to take off my gear, and stomped into the wheelhouse. It was obvious to Kane that I'd had enough.

"You don't have to like me but you have to respect me," I screamed. "I know that you're the salvage master, but I'm the archaeological director. You can't do your job and I can't do mine unless we cooperate. If you want me to continue as Treasure Salvors' archaeologist, you're going to have to cooperate."

In my anger I didn't give Kane a chance to respond. We had worked together on the Margarita site and had gotten to know one another. What I wasn't aware of was that Kane didn't even know we were down there mapping.

Mel soon came on board. He managed to tone down the feverish exuberance of the divers. His touch was magic, and over the next few days, archaeological recording procedures settied into an excellent routine. Before long, we could see the evidence of the horror of the Atocha's last moments laid out on the sea bed. With her bow ripped open by the collision with the Outer Reef, the weight of the ballast and the treasure cargo in the bottom of the ship must have sunk her like a rock.

Within the next few months the numbers of artifacts would grow: 1,041 silver ingots; more than 115 gold bars of various shapes and sizes weighing more than 250 pounds; more than 60 gold coins, most of them two-escudo pieces minted in Spain; 200 copper ingots; more than 30 wooden coin chests containing more than 100,000 silver coins; more than 750 pieces of silverware; more than 350 uncut emeralds; thousands of pottery shards, and a whole range of objects of everyday use which will tell us much about what life was like under sail 350 years ago.

But for the scientists, the main work has yet to come. Concern for the cultural value of the 1622 sites turned a treasure hunt into a project with profound implications for the future of shipwreck studies throughout the Americas.

Nothing dies that is remembered. The salvage of the vessels of the 1622 fleet has jogged our collective memory by bringing to light the property of men and women who colonized the Americas. It is these memories that Treasure Salvors, Inc., Mel Fisher, Gene Lyon, and I have worked so long and so hard to preserve. Forget the jewels, forget the gold, forget the silver. The memories are the real treasure of the Atocha.

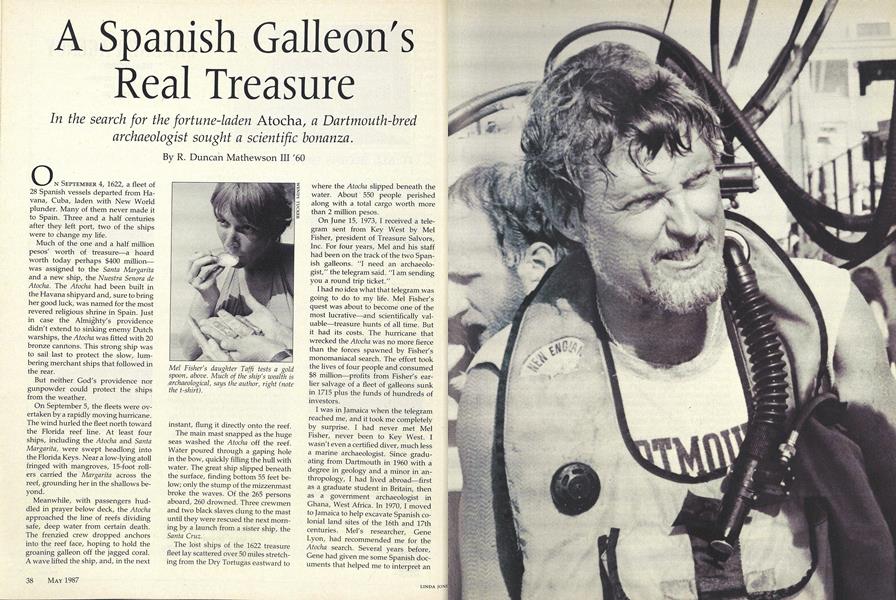

Mel Fisher's daughter Taffi tests a goldspoon, above. Much of the ship's wealth isarchaeological, says the author, right (notethe t-shirt).

Along with the treasure, hype: actor Cliff Robertson, left, played Mel, Fisher in a television drama.

"Mailboxes" on the stern of the treasure-hunting vessel deflected prop wash to uncover treasure.

The hurricane that wrecked the Atocha was no morefierce than the forces spawned by Fisher'smonomaniacal search.

R. Duncan Mathewson III '60 lives outsideKey West, close to the wreck of the Atocha. This article is excerpted from his book, Treasure of the Atocha, with permissionby Pisces Books, New York, and SeafarersHeritage Library, Woodstock, Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

May 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureThe Uncompetitive Society

May 1987 By Richard D. Lamm -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

May 1987 -

Sports

SportsA Fast-Balling Junior Mulls Going Pro

May 1987 By Jim Needham -

Article

ArticleStan Brakhage '55: "The Picasso of Cinema"

May 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

May 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Features

-

Feature

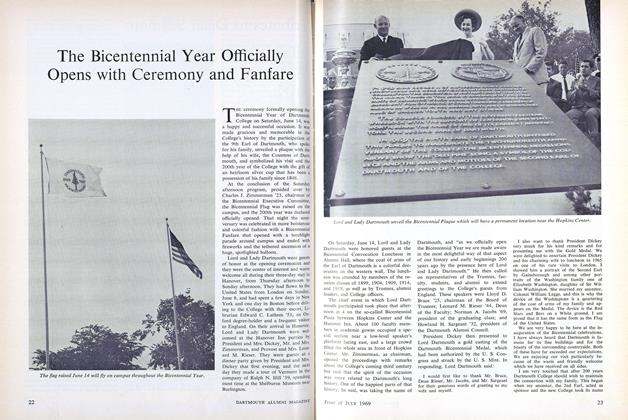

FeatureThe Bicentennial Year Officially Opens with Ceremony and Fanfare

JULY 1969 -

Feature

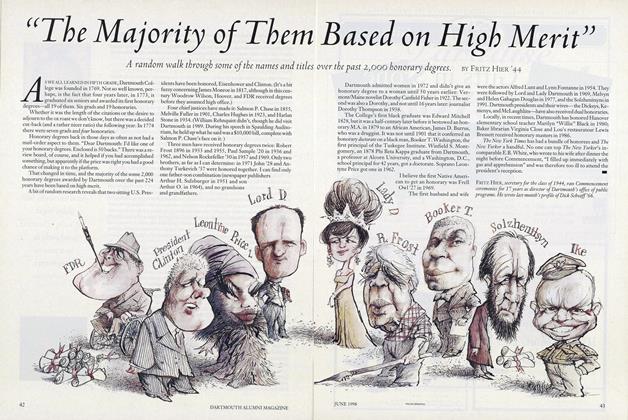

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

JUNE 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

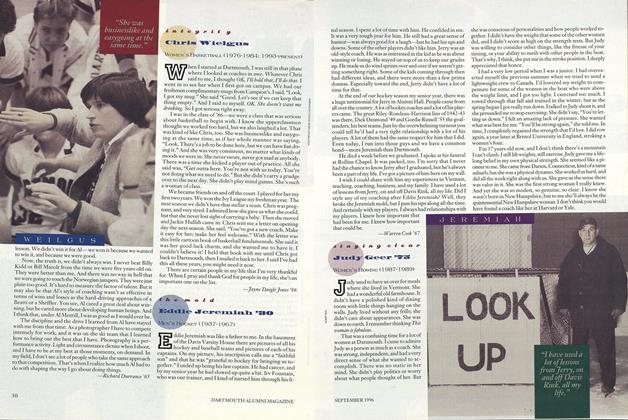

FeatureIntegrity

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jayne Daigle Jones '86 -

Feature

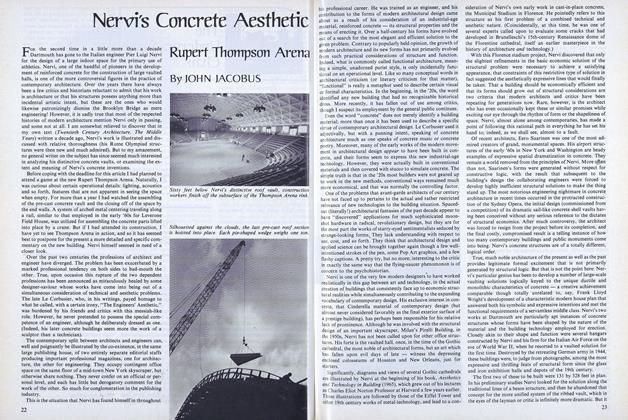

FeatureNervi's Concrete Aesthetic

January 1976 By JOHN JACOBUS -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May/June 2013 By Julia Miner ’76