IN PROGRESS

Most of the 600 or so reuning Dartmouth alumni from the classes of the late 1960s looked much the same: a few extra pounds, a little less hair than they had during their undergraduate days. You couldn't tell the haunted from the untouched just by looking at them. There was no obvious hint that they are members of a generation that bears the scars of a war unlike any other in the history of this country.

They were listening to a research progress report given last June by three psychiatry professors from the Dartmouth Medical School. The researchers—Matthew Friedman '61, Stanley Rosenberg and Paula Schnurr are conducting a unique study of the classes of '67 and '68 to see how they have coped with the Vietnam War. The research grew out of a heated reunion discussion five years ago that led to the discovery of priceless data in a College attic.

Funded in part by the Veterans Administration, the researchers hope to gain understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder, a psychiatric condition that can afflict normal people who are subjected to an abnormal or catastrophic stress: an earthquake, plane crash, rape, internment in a concentration camp, war.

"People with post-traumatic stress disorder continually re-experience the trauma in their thoughts, nightmares and occasionally in flashbapks in which they believe they are actually back in the traumatic situation," Friedman reported. "They may abuse alcohol and other drugs, and they are always on guard against future traumatization."

The project got its start in 1983, when Rosenberg delivered a talk on adult male development at the class of'68's fifteenth reunion. During the discussion period that followed the lecture, the several hundred classmates began debating the effects that the Vietnam War had had on their lives. The alumni "revealed a sharp bifurcation," Rosenberg later wrote in a research proposal. "Many argued that Vietnam and its attendant upheaval were no more than a developmental blip, its effects long ago having washed out; others that the Vietnam era had left an indelible imprint."

Several members of the class revealed that day that there was a means to measure the extent of that imprint: as freshman they had taken a standardized psychological profile that the College at One time administered to new classes "apparently to keep an eye on 'head cases,' " Rosenberg says. After an intensive search, he found what he needed in the attic of Parkhurst Hall: the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, a detailed written examination that he says is the psychological "gold standard."

The inventory's baseline data allow the researchers to see if sufferers of post-traumatic stress showed signs of being vulnerable to the disorder before they experienced trauma. According to the researchers, previous studies have had to rely on subjects' often-inaccurate memories to recreate a picture of their pre-trauma attitudes and psychological make-up.

The Dartmouth research is already yielding some results that differ dramatically from the media image of the "trip-wire vet" the burned-out, isolated ex-soldier. Out of the 100-plus study participants who served in Southeast Asia, fewer than a dozen have been diagnosed as having posttraumatic stress disorder, and their symptoms appear much milder than the popular picture. "By and large the Dartmouth graduates who have combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder function at a higher level than the media would have us believe," says Friedman. "They appear to be much like their classmates in terms of their success in life."

One reason may be that the Dartmouth group is "hardier and more resilient than the general population," Rosenberg speculates. He and his colleagues are assessing the significance of their observation that "Dartmouth veterans who fought in Vietnam were older, better educated, mostly Caucasians and probably were more likely to be officers than the average veteran."

The researchers will also be comparing the Dartmouth cases of posttraumatic stress disorder to a new Veterans Administration study. At least 15 percent of all veterans who served anywhere in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam war have posttraumatic stress disorder, according to the V.A. study, which also indicates that as many as 38 percent of veterans with high combat exposure have the disorder.

So far, the Dartmouth research is bearing out the contrasting attitudes that were expressed at the '68 fifteenth reunion discussion. Many of the study participants, including many who did not fight in the war, say that the era strongly influenced their life decisions as well as their current political outlooks. Yet some people who did serve in the war claim that the experience "didn't make any difference in their lives," according to Friedman. Some combat veterans have even told the researchers that the Vietnam experience was positive, pushing them to focus their values, become leaders, and test their physical and mental limits.

But the psychiatrists have not spoken to as many alumni as they would like. They have sent questionnaires to the entire classes of '67 and '68; so far a third of the '67s and more than half of the '6Bs have responded. Of these, 160 are being studied in depth. Each of the 160 gets a freeranging interview—Rosenberg, Friedman and their five-member research team have spent countless hours on the road to conduct interviews in person. In addition, the indepth participants take the same Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test that they took during freshman year. Friedman says that reactions to the interview have ranged from "tolerant" to "frankly confessional." "For some it is the first time they have opened up to a stranger who has some credibility."

Friedman, Rosenberg and Schnurr hope that even more members of these classes will come forward, especially those who served in combat units in Vietnam. The researchers can be reached at the Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH 03755; telephone 603/646-5834.

Karen Endicott is this magazine's faculty editor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureThe Compleat Engineer

December 1988 By Samuel C. Florman '46 -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Who Invented the Ant Farm (Not to Mention the Ant Coal Mine)

December 1988 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleCUTTING BONE

December 1988 -

Article

ArticleBEYOND INTUITION

December 1988 By J. Laurie Snell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1988 By Eric Grubman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleTHE NATURE OF REALITY

MARCH 1989 By Bruce Pipes, Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

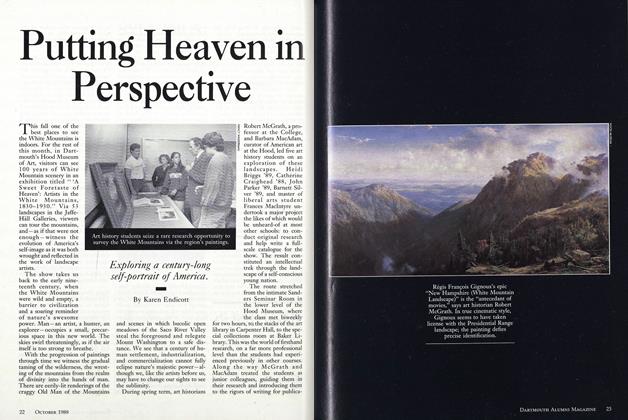

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

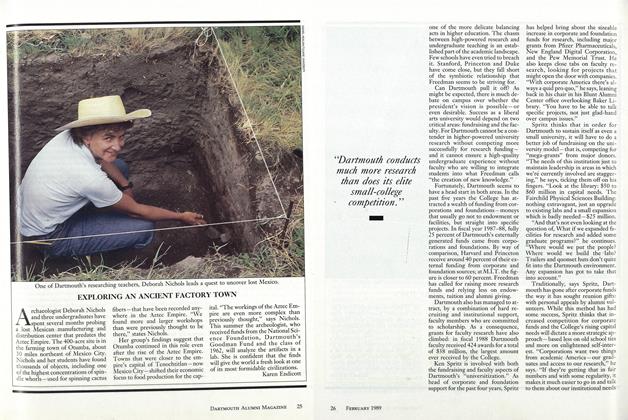

ArticleEXPLORING AN ANCIENT FACTORY TOWN

FEBRUARY 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGaudeamus Igitur!

September 1993 By karen Endicott -

Cover Story

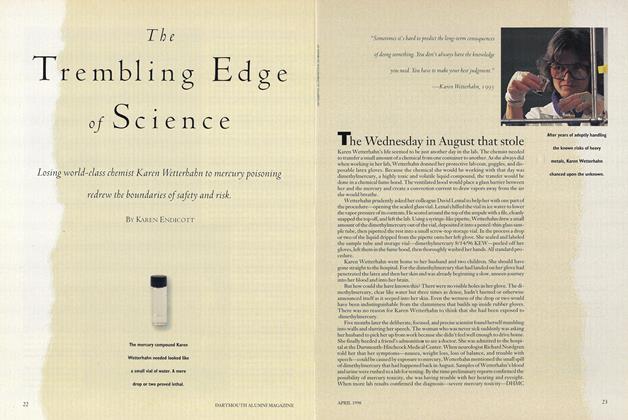

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMThe Answers Are Blowin’ in the Wind

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

JUNE 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

DECEMBER 1969 -

Feature

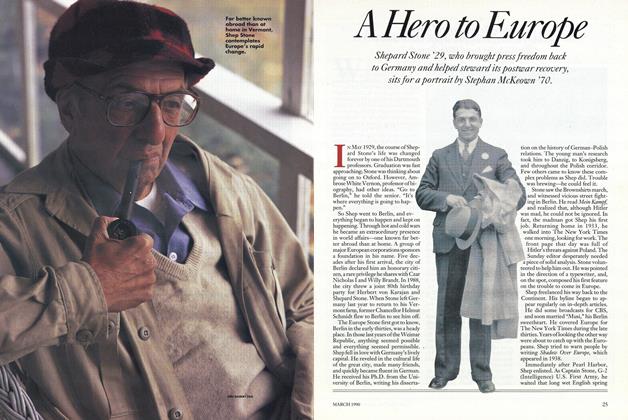

FeatureA Hero to Europe

MARCH 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"See the Beautiful Architecture"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

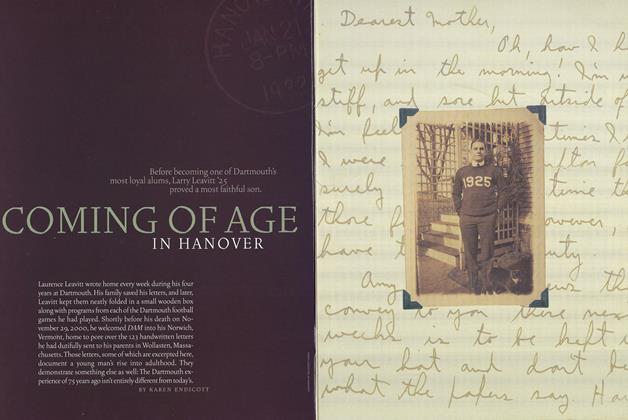

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

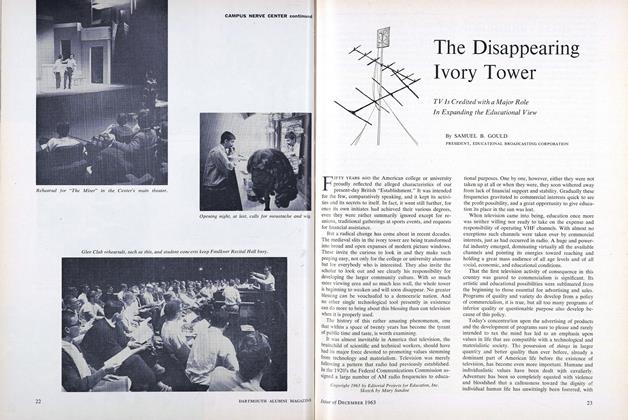

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

DECEMBER 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD