Students who merely read the Koran are missing the point.

Teaching Islam at Dartmouth, or anywhere else for that matter, requires clearing the ground in order to build. In the religion department, I find that students who walk into a course on Christianity genuinely know something about Christianity, even when they think they don't; we live, all of us, in a Christian (some might say post-Christian) culture. On the other hand, students who take a Hinduism course don't know anything about the subject, and know they don't; they begin with minds relatively unencumbered.

But students who take an Islam course arrive loaded with pseudo-information absorbed through years of reading newspapers and watching television. The first thing an Islamics instructor has to do is call their attention to what it is they think they know. Thus, the first readings we do for Religion 8, Introduction to Islam, are excerpts from a novel by Leon Uris and a piece from Newsweek, so that students can discover for themselves the assumptions that Westerners (particularly Americans) make about Muslims and Middle Easterners that they are violent, irrational, fanatical, and utterly different from our peaceful, rational, reasonable selves.

Aside from prejudicial stereotypes, there are still other quite natural and reasonable assumptions Westerners make about things Islamic that also inhibit an accurate understanding of Islam. For example, the Koran is simply assumed by most students (as well as journalists and some "experts") to be the Muslim Bible and what could be more obvious than that? Yet in fact there are two problems for Westerners when they approach the Koran: what they look at is not in Arabic, and what they read is not meant to be read.

The Koran defines itself as a "clear, Arabic Koran"; its very essence is its eloquence in Arabic; it is this eloquence that gives it the inimitability that is, in Islamic understanding, its miracle. To approach the Koran in anything other than its own language is to miss its point, and though there have been translations of the Koran for the last 1,200 years at least, none has any standing among the religious, unlike, say, the King James Bible for English-speakers.

The second barrier is that Islam's greatest "literature" is not meant to be read. Recent Western scholarship on the Koran has finally begun to take seriously the meaning of its name: Qur'an means "a recitation," even perhaps "a lectionary." It is meant to be recited and heard. When one travels in the Islamic world the Koran is audibly encountered in every possible context echoing from mosques, keening from a bereaved household, singing out from a house that has been blessed by some fortunate event, trilled and lisped in elementary schools, and pulsing constantly from radio and television.

The Koran is not a set of books, like the Bible, but is a collection of insights, poetic apergus, and even pep talks, strung together seemingly at random in a book about the length of the New Testament. Muslims, it seems to me, understand the Koran as we understand poetry: as a series of images that—taken together create something very much more powerful than the sum of any of its parts.

I encourage students to do their Koran assignments when their roommates have gone to the library. They read the passages aloud (and feel pretty silly doing it,-1 suspect), trying to get something of the flavor of the original. The result is an imperfect appreciation of the Koran, but it is one that undoes some of the assumptions we all have at the beginning, and starts us along the road to understanding Islam as Muslims understand it. Once that understanding is in place, other kinds of analysis and interpretation can be used to understand how Islam "works."

Islamicist Kevin Reinhart

"Could a Muslim in California use a hot tub? Would it be Islamically legal?" Assistant Professor of Religion Kevin Reinhart asked his 30 startled students in his course on The Islamic Tradition last fall. He paused for the laughter and went on to instruct his class in the fiqh process how to apply Islamic law to new situations. "In the case of hot tubs the Koran is silent, so we have to find examples that are as close as possible to the problem and then extend the logic." Reinhart explained. "We know that men and women ought never be publically unclothed and ought to associate with each other only in the context of family life. We also know that the Koran commands Muslims to bathe in certain circumstances. Therefore, 'Kevin's Ruling on Hot Tubs' is that it is okay to use them if you remain folly clothed and go only with members of your own sex." He looked up. "So we see that the idea that Islamic law is stagnant or rigid isn't necessarily the case. Now, what about cross-country skiing?" he asked, launching into another round of interpretation. Reinhart's facility with Islam began early. As a teenager he lived in Turkey for two years on a U.S. Air Force base. He returned to the Middle East several times en route to a double B.A. in Middle Eastern Studies and Arabic from the University of Texas at Austin and spent two years in Cairo and Yemen researching Islamic legal and moral theory for his doctorate in religion from Harvard. Reinhart still travels as often as he can to Islamic areas for his own research and, on Dartmouth's behalf, to investigate opportunities for foreign study programs, recruit students, and establish contacts to aid the College's new program in Arabic. Reinhart would like to see all Dartmouth students exposed to Middle Eastern studies. "It seems to me that any student with a liberal arts education ought to know something about the billion or so Muslims whom we see more and more prominently in world affairs." Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

September 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

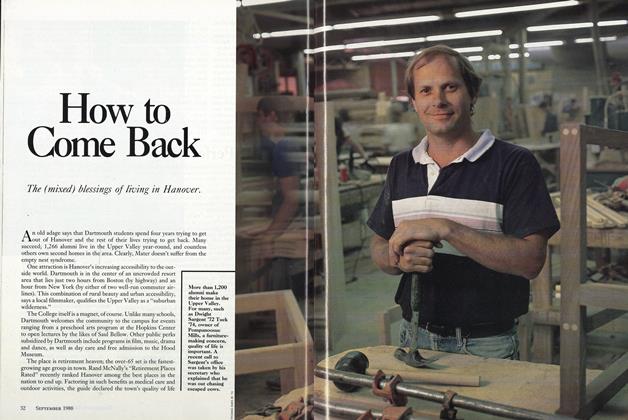

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988

A. Kevin Reinhart

Article

-

Article

ArticleFIRST GENERAL REUNION, MEDICAL ALUMNI September, 1912

-

Article

ArticlePortrait Catalogue

January 1933 -

Article

ArticleTHE FBI AND ME or, How I Didn't Shoot Eisenhower

November 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING'25 -

Article

ArticleTHE BASIS OF DISCIPLINE AT DARTMOUTH

December, 1914 By Dean Craven Laycock '96 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

FEBRUARY 1967 By HARRY W. SAVAGE M' 27 -

Article

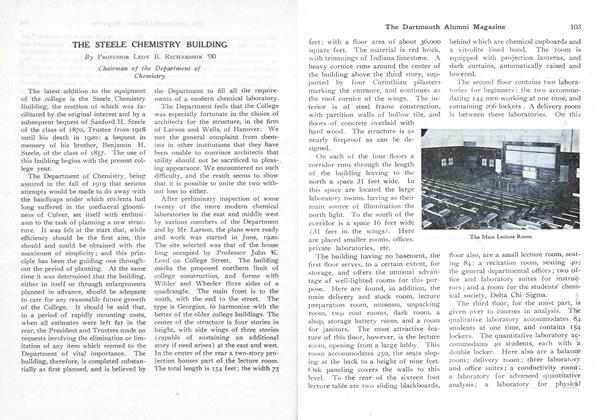

ArticleTHE STEELE CHEMISTRY BUILDING

December 1921 By LEON B. RICHARDSON '00