Attitudes are changingabout Dartmouth'smost damaging drug

THE YEAR WAS 1920. The Dartmouth campus was dry but then, so was the whole country. On a Wednesday night in June, Henry Maroney' 19 went in search of bootleg liquor. His quest led him to the room of Robert Meads '20, who demanded $20 for a bottle. Maroney had only $8 in his pocket. The two men began to quarrel, and in the early morning hours Meads shot Maroney dead with a pistol.

The incident helped to shape President Hopkins's pragmatic view of Prohibition, according to his historian, Charles Widmayer '30. "The Hopkins attitude did not condone student drinking," writes Widmayer, "but years of trying to halt it had brought him to the point of being as realistic and candid on the subject as any college president could be at the time." Legend has it that Hopkins and the region's best-known bootlegger had a gentlemen's agreement that the College would not pursue legal action provided that students were sold "safe" liquor.

Prohibition is over, but pragmatism still prevails. At least two-thirds of the student body are too young to drink legally, yet on an average Friday night very few go thirsty involuntarily. To counter the ill effects of Dartmouth's most damaging drug, officials have begun to combine tighter regulations with increasing amounts of counseling and education.

The good news is that Dartmouth's reputation as a heavy drinking institution is largely unearned—or at least no longer true. The amount of actual drinking on campus has dropped steadily since the mid-seventies (due in no small part to the addition of women, who tend to drink less). The number of students drinking daily at Dartmouth has actually dropped below the national average. "I don't think that Dartmouth is dramatically different from any other school," says Jack Turco, director of the College Health Service. According to a 1988 survey, 3.3 percent of Dartmouth students reported drinking daily or almost daily; the national figure among college students hovers around six percent. Twelve percent of the campus does not drink at all, and a quarter of the students are having one drink or less per week, according to Phil Meilman, coordinator of Drug and Alcohol Programs and author of the survey. The average student downs just five drinks weekly. The best news of all may be that attitudes seem to be changing. "Heavy drinking has been deemphasized since I was a freshman, and I remember the '88s saying that it had been going down since their freshman year," says Allison Schutte '91.

But the battle against abusive drinking is far from over. "It's a very skewed distribution," warns Meilman. "You have to look at the whole picture." His results show that nine percent of students on campus are consuming 20 to 50 drinks a week. Among this group, what is viewed as normal drinking behavior would be considered wildly excessive by more objective standards. "Drinking at Dartmouth is like crossing the street in Hanover," says Rahn Fleming '81, Dartmouth's substanceabuse specialist. "You just can't do it in the outside world like that and get away with it."

I should know. A member in good standing of Alpha Delta, shortly before graduating from Dartmouth in 1988 I went for a job interview with the CIA in Langley, Virginia. I was two hours into the standard polygraph test and was doing well on the questions about serving my country when the examiner changed subjects. "How often do you drink to the point of getting drunk?" he asked.

"Do you get drunk on Friday and Saturday?"

"Certainly there have been times," I conceded.

"Do you drink during the week?" "Wednesdays are house meetings, and Thursdays are cocktails at Zeta Psi."

"Do you get drunk?" he prodded.

"Sometimes."

"So you get drunk Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights," he concluded in an amazed tone.

It was a startling summary, but I didn't argue. I was just happy he didn't ask about Monday Night Football.

Alcohol may have cost me a job as a spy, but it's not the root of all evils. Most students will tell you that drinking can release stress, lower inhibitions, provide a sense of belonging, and generally facilitate socializing. As President Hopkins learned, a completely dry campus is not an option. Even the most vehement critics of the Greek system concede that "social alternatives," a term bandied around Hanover since the days when students arrived on horseback, are still lacking. At present, non-drinkers find a dearth of late-night activities. Rather than being a social lubricant, alcohol becomes the glue that holds the whole system together.

But drinking is more than just something to do; there is a certain glamor to alcohol. Beer companies spent a combined $750 million on advertising in 1988, and the effect is not lost on Dartmouth. Drinking, especially fast and hard drinking, retains its positive image. Rahn Fleming recalls his arrival as an alcohol counselor at Dart mouth: "The first three weeks I was here all I heard about was that Tri-Delt [a sorority] had beaten Sigma Nu [a fraternity] in a chug-off. Everybody was excited, especially the Tri-Delts." When Harvard Medical School researcher Henry Weschler conducted a 1977 study on drinking patterns at New England colleges, he got calls from Dartmouth students curious about the results. It was a point of pride that Dartmouth exceeded the national norms. But Dartmouth has no monopoly on the macho drinking image. Fleming says that at a recent Department of Education conference "there were people from two or three hundred schools who swore they were on Playboy's list of the top 40 party schools." (Dartmouth got an honorable mention.)

Says Mary Turco, dean of residential life, "People have glorified alcohol on this campus. Chris Miller is the perfect example." Miller '63, most famous for having co-written the "Animal House" screenplay, created the stereotypical college experience and it involved no small amount of drinking. In an article in the September issue of this magazine he described recreational vomiting as "richly satisfying."

"The thing that's really macho right now is to vomit," Dean Turco says. "That's part of the Dartmouth culture that I don't understand."

No group is more vulnerable to the macho drinking image than freshmen. When most of them arrive on campus, they are two, sometimes three years away from drinking legally. But they do it anyway, and they do it, more than any other class, in excess. "I think it's a breaking-out process in the freshman year," says Keith Dunleavy '91, student area coordinator for the Russell Sage-Butterfield dorm cluster. "For so long they haven't been able to do it. It's the cookie jar on the shelf syndrome. For a few months they gorge themselves and then realize, 'What's the point?"' During the fall term of 1989, 24 students were admitted to Dick's House or Mary Hitchcock Hospital for alcohol-related injuries; two-thirds were freshmen.

College gives new students a clean slate and a chance to build a new selfimage, Dunleavy explains. "A lot of them turn to alcohol to be cool." He recounts the story of a freshman in his dorm who bet dormmates he could drink a case of beer in three or four hours. That feat barely eluded the freshman; he "lost it" on can number 23. "You wouldn't believe the audience he got," says Dunleavy. "He got very upset that he missed the bet and swore that he would do it the next week." (Dunleavy spoke with him about the point of what he was doing and the challenge was not repeated.)

Official policies notwithstanding, freshmen will be freshmen. "This is what Chris Miller talks about; it's a rite of passage," says Jack Turco. "I'm agreeing on the level that there will be experimentation. What you have to realize is that a lot of people get burned during that rite of passage."

Exactly who gets burned and how badly is difficult to quantify. Alcoholism strikes some Dartmouth students-not 20 years down the road, but while they are still in school. James '88 (not his real name) has a wistful look as he discusses his own battle with alcoholism. "I was in trouble before I came to Dartmouth; there's no doubt in my mind," he says. Both his grandfather and great-grandfather were alcoholics. Although the genetic component of the disease is still not completely understood, researchers say a person is four to nine times more likely to develop alcoholism if it runs in the paternal bloodline. Nonetheless, for several years the Dartmouth "work hard, play hard" ethic disguised James's problem drinking. "I had an illusion that everyone drank like I did—that everyone got drunk every weekend," he admits. After being confronted by friends and acknowledging that he was dependent on alcohol and other drugs, he made the decision to seek treatment outside the College.

Twenty-seven students have been sent to in-patient treatment centers for alcohol and drug rehabilitation in the past three years, and up to 70 students a term undergo on-campus counseling at Dick's House—primarily for alcohol problems. For the skeptics, counselor Rahn Fleming points out, "On any night of the week you are not more than a ten-minute walk from an AA meeting in Hanover. That is how much need—and response—there is."

The drug's effects go beyond the individual to color the whole institution. Alcohol abuse is an accomplice to sexual assault, dorm damage, academic failure, and most other student problems. How much so is hard to determine. "These are bright kids; most of them can get by at Dartmouth on two-and-a-half cylinders," says Jack Turco. My friend James is a good example. He had a respectable 3.2 cumulative average before withdrawing in 1986 to seek treatment for alcoholism. He has managed a 3.8 since his return.

Sexual assault and pregnancies are easier to measure. "We have 20 to 40 unplanned pregnancies a year," Jack Turco says. "Most of those involve alcohol." Dean Mary Turco reports that alcohol is involved in roughly 90 percent of the more than 100 sexual assaults that take place at Dartmouth in any year. Usually, both parties have been doing the drinking.

And then there is liability. When Bluto, Otter, and the rest of the disheartened brethren of the Delta House rallied to have a toga party at the climax of "Animal House," they didn't have to worry about getting their pants sued off them. That specter now hangs over every drink served at Dartmouth. Liability laws have been getting more expansive, according to College lawyer Sean Gorman '76. Dartmouth has never been sued for an alcohol-related incident, but a 1988 Rutgers case is evidence that the threat is real. After Rutgers freshman James Callahan died in a 1988 fraternity hazing incident, his mother filed a wrongful-death suit against the fraternity, its members, a liquor store, and the university itself. "If you have a good lawyer, he's going to sue everybody in sight, including the College," points out John Engelman '68, president of the Alpha Delta Corporation. "In fact, he's probably going to sue the College first because it has the deepest pockets." According to New Hampshire law, those providing the atmosphere where abusive drinking has taken place, even if they do not serve the alcohol, are responsible for the conduct of any person drinking there.

Still, the main concern of Dartmouth alcohol policymakers isn't lawyers; it's keeping students alive and healthy. The College alcohol policy now stipulates that "when a student or organization assists an intoxicated student in procuring medical assistance, neither the intoxicated student nor the organization will be subject to formal disciplinary action for 1) being intoxicated, or 2) having provided that person alcohol." The policy eliminates a previously dangerous situation in which fraternity presidents would agonize over whether a pledge was really sick enough to justify seeking treatment and thereby incurring the wrath of the administration. "We've put a big push on getting people to the emergency room," says Meilman. "We don't want to lose anybody. Yale, Rutgers, Princeton, Cornell, and the University of Florida have all lost students to drinking incidents in the last few years."

The best solution, of course, is to stop problems before they get to the emergency room. Dartmouth is spinning a safety net that consists of student alcohol "peer educators" (80 to 120 in any given term), undergraduate advisors, and area coordinators, all of whom are trained to recognize alcohol-related problems. Entering students attend a mandatory educational program during freshman orientation, and the Coed, Fraternity, and Sorority Council sponsors a seminar for fraternity and sorority presidents during their annual retreat. Peer counselors work with every athletic team at Dartmouth. Ultimately, say the deans, the campus will be awash with students who recognize abusive drinking in its early stages.

To supplement that effort, Dartmouth received a two-year grant from the U.S. Department of Education which was used to hire Rahn Fleming. In addition, the Dartmouth Medical School is the beneficiary of a grant from the Ray Kroc Foundation. Kroc, the founder of McDonald's, "was diabetic and alcoholic, and he had a bundle of money," explains Jack Turco. Kroc's widow gave money to Dartmouth Medical School in the seventies for Project Cork, a program that integrates alcohol education into the curriculum.

The dean's office is the second line of defense. Any problem to which alcohol may be a contributing factor is referred by the deans to an alcohol counselor. The deans say they have lowered the threshold for making referrals. As little as four years ago, a case had to be egregious—such as a fistfight or dorm damage. Now, students caught drunk in public are routinely tinely sent to counselors. When Jud Hale '55 got drunk and vomited on the late Dean Joseph Mac Donald and his wife, he was expelled and drafted into the army. Today that escapade would earn him an appointment with Meilman (after which he would still probably be disciplined). "In the not too-distant past, alcohol was a mitigating factor," explains Meilman. "Now ifyou get drunk and misbehave, you've got two problems—you were drunk, and you misbehaved."

Dartmouth's alcohol programs aren't limited to the campus. A towngown blue-ribbon committee on substance abuse coordinates efforts in the Upper Valley with those at the College. Phil Meilman calls the committee "a model for the nation."

The emphasis on education is not without its critics, one of whom is Herbert Kleber '56, deputy drug czar under William Bennett. During a recent visit to campus, he quoted Washington Post columnist William Raspberry as saying, "Education is the cure only to the extent that ignorance is the disease." Counselors and deans need to get past students' "delusions of immortality," says Kleber, who favors punitive measures on top of education. Programs will only work "if they're not only posters and papers but the university says, 'Hey, we're serious about this.'"

Ironically, the College's most progressive answer to the dangers of alcohol is only a stone's throw from Fraternity Row. It is a house for recovering substance abusers. It is here that James, and other students like him, find the supportive environment necessary to come back and finish their degrees after being treated for drug addiction.

A haven like this is most appreciated by alumni whose battles with alcoholism were much lonelier. A compelling story comes from Jack '61 who dropped out of Dartmouth in 1959 because of a drinking problem. He sought treatment at Alcoholics Anonymous and, five years after leaving Dartmouth, came back to finish. No member of the Boston AA group had ever ventured back to school, and he admits, "There was a lot of fear in me when I came back." His experience gives him an appreciation of what Dartmouth has done to give recovering alcoholics a source of support. He says of the new housing option, "I think that is such a miracle. When I came back it was like breaking new ground."

Are the programs working? As a former fraternity president (and fraternity brother of Chris Miller), I can say that old habits die hard. The Greek system has yet to abandon beer in favor of diet Coke. The Chris Miller article is evidence that there is room for improvement. Says James, "A lot of people were upset, not because these things were going on at Dartmouth, but that Chris Miller wrote about them. In a way I was happy to see the Chris Miller article because it talked about real problems that are still going on at Dartmouth."

Despite the immutable behavior of diehard fraternity basement dwellers and macho freshman males, the mainstream attitude on campus appears to be moving in a healthy direction. James offered an objective appraisal of the situation after he returned to campus. "Things have gotten better since I came in the fall of 1984," he said. "It's no longer automatically cool to chug, boot, and die." John Engelman, who has been affiliated with AD for 20 years-first as a member and then as corporation president—agrees. "I see fewer people doing serious drinking before or during house meetings," he reports. "In the late seventies and early eighties you'd see guys coming down to start drinking at seven or eight. You don't see that much anymore." A study conducted by Dick's House during the fall term of 1986 showed that Wednesdays, when fraternity and sorority house meetings are traditionally held, had the lowest incidence of alcohol-related related injuries of any day of the week.

On an individual basis, hope may lie in the growing-up that students do at Dartmouth. Even before I had gone for my CIA interview I had begun to be disillusioned with the hard-drinking fraternity life. I don't get drunk four nights a week any more; in fact, I rarely do much serious drinking at all. I haven't just sown my wild oats; the wildness itself has lost its appeal.

Institutionally, though, changing attitudes is a long-term undertaking. Dartmouth is part of a larger society that has not yet faced up to the dangers of alcohol. Jack Turco relates the story of a student who was brought into the emergency room in dire shape. He had aspirated his vomit, and a breathing tube was the only thing keeping him alive. Turco placed the call in the middle of the night that every parent fears. "I told his father, 'Your kid may not live.'" After half an hour of conversation, the father, who considered himself well versed in the antics of college students, said, "So, do you think I ought to come up tonight?" Turco shakes his head incredulously as recalls his answer. "I said, 'Your kid may die!'"

The student lived. In fact, the lack of students killed by alcohol in recent memory is a tribute in part to the safer environment the College has created—one in which people who need help will get it. "Dartmouth has done well over the past five years, which is not saying that it can't get better," says Turco. "We're not going to eliminate abusive drinking in the immediate future. Dartmouth should be happy with slow, steady progress." That great pragmatist, Ernest Martin Hopkins, would likely agree.

"I'm a son of a gun for beer," the song says, but many no longer fit the description.

After years offighting it,Hopkinsbecame apragmatist.

Phil Meilman says a quarter ofDartmouth's students have onedrink or less per week.

When Rabn Fleming '81 washired, all be beard about was howa sorority outchugged a frat.

Deputy Drug Czar Kleber '56favors strict punishment.

Dartmouth's heavy-drinkingreputation now seems unjust.

Alcoholmay have cost mea job as a spy, butit's not the rootof all evils.

Despite the immutable behaviorof diehard fraternitybasement dwellersand machofreshman males, themainstream attitudeon campus appearsto be moving in ahealthy direction.

Charlie was summer presidentof Alpha Delta during his junior year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

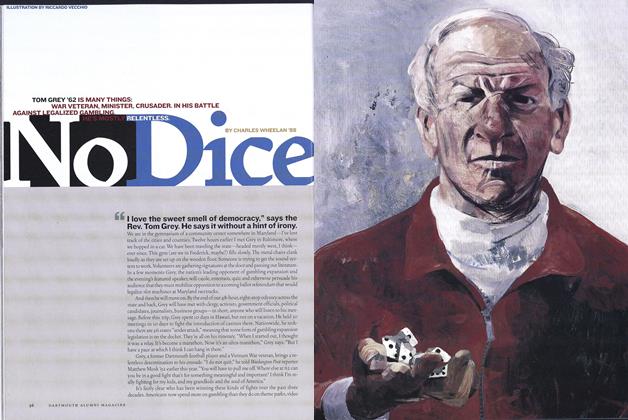

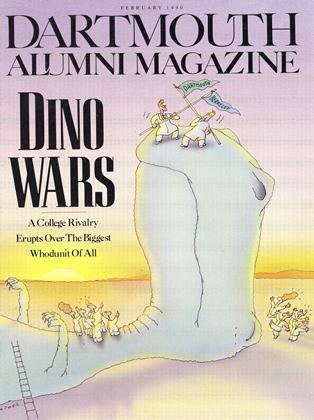

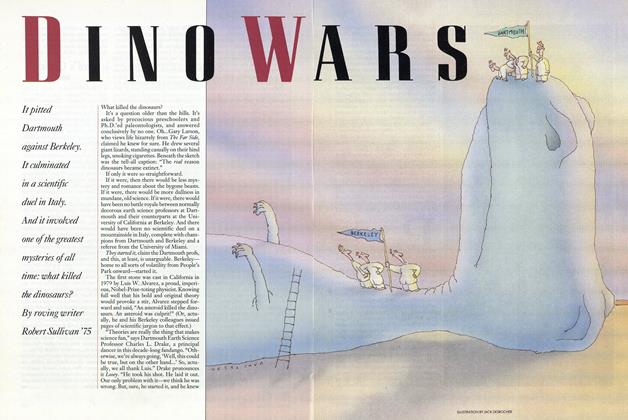

Cover StoryDino Wars

February 1990 By Roving Writer Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureIf You Thought the Comps Were Hard, Try This Quiz

February 1990 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

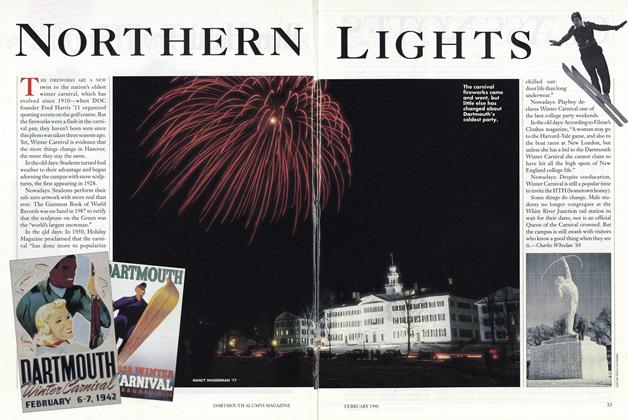

FeatureNorthern Lights

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1990 -

Article

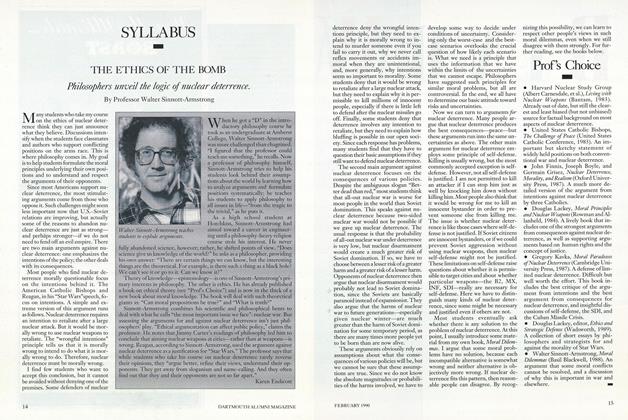

ArticleTHE ETHICS OF THE BOMB

February 1990 By Professor Walter Sinnott-Armstrong -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

February 1990 By W. Blake Winchell

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStudents

June 1980 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

APRIL 1991 -

Feature

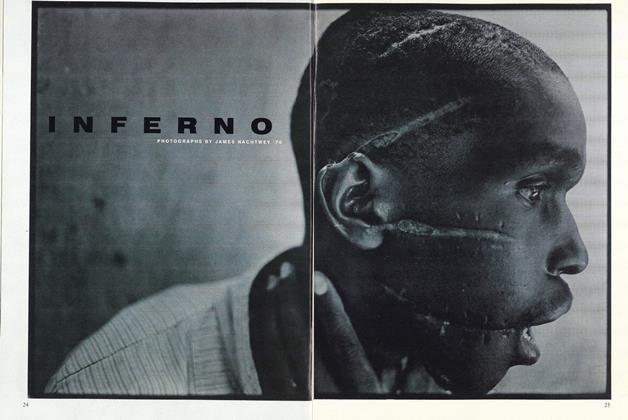

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Public Eye

March 1954 By FRANCIS BROWN '25 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

MARCH 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

Mar/Apr 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95