The Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

SEPTEMBER 1990 Robert Sullivan '75The Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club Robert Sullivan '75 SEPTEMBER 1990

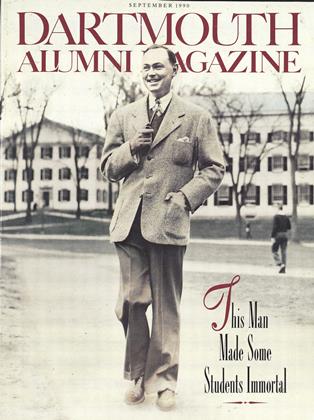

How a pamphlet in the Hanover Inn led the author to Corey Ford the funniest writer ever to work for the College.

FIRST MET COREY FORD AT the Hanover Inn.

Correction: I never did meet Corey Ford, not in the hail-hail, shaking-of-hands sense. I never even saw the man, though perhaps I saw his shroud. Ford may have been among those anonymous ghosts I noticed drifting across the Green on foggy November mornings in the early seventies. As I recall it, there were a lot of tweed-coated, pipe-smoking gentlemen with dogs at their heels crisscrossing the Green back then. That's one of those Hanoverian images I retain from my Dartmouth days. One of the specters might or might not have been Ford, restless still since the man had shuffled off this mortal coil only lately, in 1969.

The thing is, I was first introduced to Corey Ford at the Hanover Inn. I met him in the way that you meet any facile writer who, through his writing, welcomes you into his world.

Back when I was in school, the folks who ran the Inn used to leave homey tokens by the bedside. Not those little Sheratonesque chocolates supplied everywhere in 1990, but tokens of less sugar and better spice.

I was visiting, once, in my parents' room at the Inn, during one of their visits to the "child away at school." I picked up the token on the bedstand, a little pamphlet printed on good uncoated stock and entitled My Dog Likes It Here. As my parents readied themselves for the football game or Lou's breakfast or whatever was on our itinerary, I lounged on the bed and started to read.

"Okay," I distantly heard my dad say. "All ready. Let's go." "Yeah.... Just a second." "We'll be late." "Yeah, uh-huh. Just a second

For I was off in Ford's world, a world I would leave with some reluctance. It was, in that essay, a world where dogs got the better of men. Retrievers and St. Bernards dominated the Hanover Plain, interrupting baseball games and stopping traffic and generally pushing the students and townsfolk around. "My dog made up my mind to live in Hanover," Ford wrote. "My dog is a large English setter, who acquired me when he was about six months old, and who has been making up my mind for him ever since. When we go out on a leash together he decides whether to run or walk or halt abruptly at the corner lamppost to mail a letter." The dogs nudged their H. sapien "masters" around Hanover for several more pages. "President John Sloan Dickey belongs to a big golden retriever, who sits beside the President's desk in the Administration Building all day and walks him home every night on a leash, to make sure Dr. Dickey doesn't run away." Corey Ford's world was a most gentle and very, very funny place.

As my parents and I walked onto the Inn's porch, I considered how lucky the hostelry was to have a talented humorist living somewhere hereabouts who could write these amusing pamphlets. I didn't know if this Corey Ford were young or old, a professor or a student or a Thetford pig farmer. Living or dead, even. Nevertheless, I figured the Inn was lucky to have access to Ford's literature. And I rationalized that the Inn must have a goodly stock of these pamphlets, as I slipped that copy into my pocket.

A decade and more passed and I was situated in Greenwich Village, browsing in the Strand Bookstore ("Eight Miles of Books Largest Used Book Store In The World"). I might've been looking for something by Ford Maddox Ford or maybe nothing in particular, when suddenly a title swam before my eyes (doing Ford would embellish the backstroke). The Time of Laughter that was the tide, aswim—by Corey Ford.

I know that name. Why do I know that name?

At the Strand, books cost precious few pesos and so I bought the dusty volume, which had been published by the venerable Little, Brown house in 1967.

The Time of Laughter is Ford's account of what James Thurber, in a more famous book, dubbed "The Years With Ross." This was Manhattan in the halcyon twenties, when everything literary seemed to revolve around three shining suns: an infant magazine named The New Yorker, its boy-genius editor Harold Ross, and the round table in the Rose Room of the Algonquin Hotel.

As I read The Time of Laughter I felt like Poirot, having stumbled upon the crucial clue. Now everything made sense. Corey Ford wasn't merely some hick tale-teller who tossed the occasional cookie to the Hanover Inn. Corey Ford was...a writer! He had been a writer of significance and high reputation at a time when the competition was spelled BENCHLEY and BROUN and PARKER and WOOLLCOTT and GIBBS and THURBER and E (period) B (period) WHITE!

Ford, I learned, had been an Algonquin irregular, splitting his time between the Beekman Place flat he shared with fellow New Yorker humorist Frank Sullivan, and distinctly non-urbane backwaters in New England and beyond. "I had the apartment to myself half the time," wrote Sullivan in his introduction to The Time of Laughter, "because Ford was away half the time.... Ford was never happier than when flying over the Himalayas, or catching salmon in Alaska, or collecting virgins in Bali."

Ford was half nightclubber, half out-doorsman. He was therefore something of a square peg at the round table, and this may be why his name has traveled through the years with less attendant ceremony than his contemporaries' bylines. Benchley and Broun were in with the in crowd; Ford was in and out.

I was excited by my find. It became my habit to travel the "F" shelf at the Strand often, and I added to my collection of Fordiana. The Time of Laughter wis, in fact, Ford's 30th book, and his oeuvre included seven volumes of parody, another eight collections of his humor, a few war books, and five books on outdoor life. I found a satire of seafaring yarns entitled Salt-Water Taffy; it was silliness personified. Ford's most famous piece, How to Guess Your Own Age, had been published in its own slim edition and I grabbed that. Corey Ford's Guide to Thinking was riotous, although it gave no clue to the man's singular mind.

One day I strolled by the book review editor's office at the magazine at which I work and I saw a bulky, leather-bound, deluxe volume at the bottom of one pile: The Corey Ford Sporting Treasury. I sauntered in, casually knocked the pile onto the floor and began flipping through the book. "You want it?" the editor asked, having been made aware of my presence by the crash and boom. "Take it. Review it, if you like."

It was a collection of 49 satires Ford had written for Field &Stream, plus a few more serious, sentimental, even somber stories about bygone hunting dogs. It was a great book, and I gave it a glowing review, which must have pleased the obscure Wautoma, Wisconsin, publishing house that had resurrected these pieces of Ford's.

The review led to another quirky turn on this Corey Ford shunpike. Ford fanatics starting coming at me from the woodwork. I was sent personal letters from long-lost friends I'd never met, each envelope containing little bits of Ford arcana. A favorite was from a friend indeed, Dave Shribman, a Dartmouth classmate and now an estimable political reporter for The Wall Street Journal. "Quaint country inn bullshit," wrote Shribman, having found me out. "That's the Hanover Inn! That's where I first found Ford, too. Some essay about a d0g..."

And now the reason for recounting all this. As it happens, a member of this surprisingly large Ford cult is the editor of this here alumni magazine. When I mentioned to him that I'd like to investigate Ford's Dartmouth connection in a piece, he got all excited. He said something along the lines of, "Corey Ford? Haaell yes! You've read Corey Ford?? Doit!"

And so here I sit, having re-read Ford, having talked to people who knew him or knew of him in Hanover, having gathered together Ford lore and legend, trying to convey a sense of the man.

Corey ford was born simulianeous with our century somewhere in or around New York City. He went to Columbia, where his writing got started. Ford recalls: "At the start of my sophomore year I was elected editor of the college comic magazine, the Columbia Jester, and when I entered the fraternity house for lunch that day they rose and cheered me, the first time I had ever been cheered. I think that was the moment I decided to be a humorist."

Chronicles of bygone literary circles, from the round table to Bloomsbury, inevitably read like pretentious exercises in name-dropping. Nevertheless, there's a truly remarkable paragraph in The Time of Laughter that points up the luster of Ford's chosen society:

"Back in the Twenties the college comics were in their heyday, an invaluable proving ground for budding humor writers. As editor of the Jester, I followed in the distinguished footsteps of Bennett Cerf and Howard Dietz and H.W. Hanemann. Robert Benchley and Gluyas Williams and Robert Sherwood had graduated from the Harvard Lampoon, Cole Porter and Peter Arno from the Yale Record. S.J. Perelman edited the Brown Jug the year after I graduated. Joseph Bryan III ran the Princeton Tiger and Hugh Troy was at the Cornell Widow. Theodor Geisel was turning out weird and wonderful cartoons signed 'Dr. Seuss' for the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern, and James Thurber first drew his doleful dogs for the Ohio State Sun-Dial."

All of the above did their post-grad work at The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The Saturday Evening Post, and the old Life (with night classes at Moriarty's, "21," Toots Shor's, and the Algonquin). That lineup became the '27 Yankees of wit: there hadn't been anything like them, and there hasn't since.

Although Ford was held in high regard by his peers, not everyone in his readership knew who he was. He was the Ted Geisel of adulthood: several of the things he did best, he did pseudonymously. Just as kids have long believed in Dr. Seuss no less religiously than they have in Santa Claus, so did their forebears in the twenties believe that Vanity Fair was employing a deft parodist named John Riddell, who each month delivered a brilliant send-up of a current best-selling book.

"Since I was already writing a monthly article for Vanity Fair, I decided to sign the parodies with a nom de plume," Ford recalled. "My method of selecting a pseudonym was to shut my eyes, open the New York telephone directory at random, and put my finger on a name. The name turned out to be Runkleschmelz, so I threw the phone book away and though up 'John Riddell,' a clever rearrangement of the letters of my own name." The Riddell stories ran ten years and filled three books, including The John Riddell Murder Case, a best-selling take-off on the detective genre as exemplified by Philo Vance potboilers.

A quick dip into Riddell is mandated by any discussion of Ford. Here, Ernest Hemingway, having fought the bull to a draw, brings his new compatriot to the cafe and introduces him to Ford...er, Riddell:

"I want you to meet my friend, Mr. Riddell," said Hemingway. "John, this is the bull." "Well," said the bull.

"Three Anis de Toro," I said to the waiter.

"These drinks are on me, by the way," the bull said.

"No, I've got it," says Ernest.

The waiter paused with the bottle on his hip. "Do you want them with water, Ernest?" he said.

"No, I'll take mine straight," says Ernest, "Short and straight."

"Corto y derecho" said the waiter.

"That's right," Ernest says.

The waiter filled the glasses.

Scott Fitzgerald reported to Ford some years later that he, Fitzgerald, had read the parody aloud to Hemingway during one of their boozing sessions at the Ritz bar in Paris. Hemingway had left the bar "corto y derecho," as Ford liked to tell it.

Then there was the How to Guess Your Own Age incident, which took the idea of a writer's anonymity to a new low. One morning, as Ford found the pangs and pains of middle age creeping in, he scribbled an amusing sketch on the subject. How to Guess Your Own Age mused over how much higher stairs went these days, how much farther away the store was and how much longer the trip took. How much sooner a martini hit you.

HTGYOA was so simple, so clean, so generic, so perfect and classic a piece, people assumed it had always been there. It was instant Americana; next to nobody realized it had been written by Corey Ford. His byline was seldom attached to it, as it appeared on everything from Christmas calendars to advertising circulars. Ford eventually sicced a lawyer on a couple of the more public plagiarists, those who were claiming the piece as their own in the professional press. He was soured by the whole experience.

"Ford would rate high in Dun & Bradstreet today if he had been able to collect royalties from all these stolen reprints of How to Guess Your Own Age," Frank Sullivan speculated in 1967. "He still winces at the memory of that wholesale larceny."

"Yes, indeed he took such things seriously," recalls James Hall '55, who knew him well, both before and after college. "Corey always lived by his wits, which is a difficult and nervewracking way to make a living. I think the early poverty made him conscious of having money coming in regularly. A few times, I believe he did have money problems. It was difficult. So he would get up and write every morning, every morning, pencil on a yellow legal pad. That was how he made his living, and that allowed him to be generous to his friends, and he was."

In the twenties and thirties when Ford had one book following another to the shelves and articles on New York newsstands every month, he was a bi-coastal party-boy. He had friends in Hollywood, including his bosom pal W.C. Fields. And he had his Manhattan cronies. Like many of his contemporaries, Ford had difficulties settling down. "He never married," says Hall. "There was an actress once, in Hollywood, and I believe they were going to be married. But at the last moment it didn't work out. That's all he ever said about it, really. He had romantic entanglements after, but never married."

All the intoxication of New York and L.A. in those years wasn't enough to keep Ford anchored at Beekman Place; as much as he liked the city, he needed the country. In his traipsings through the outback he had stumbled upon, and fallen for, the felicitously named Freedom, New Hampshire, which is 75 miles northeast of Hanover. He built a lavish stone "cabin" and kept it for a few years, finally settling in Hanover itself.

His residence in the Upper Valley was less strange than his former halls of Freedom. (Sorry—in writing about Ford, it's requisite to leave no pun unturned.) Ford settled cozily in a white Victorian on North Balch, a couple blocks from campus. "That's where I first met him," says Jim Hall. "Sid Hayward was the secretary of the College and an avid outdoorsman. He had a cabin south of town at Pleasant Lake, and spent a lot of time there. Anyways, I was from a little town Travers, Michigan—and when I matriculated I said that hunting and fishing were interests of mine, so I was assigned Sid as my advisor. He introduced me to his outdoor friends, and the main one was Corey.

"We used to meet at his house all the time and talk. He'd smoke his pipe, and Cider would sit by his chair. That was the name of his hunting dog Cider, because he only worked in die fall.

"Corey was a lonely man writing's a lonely life and so he befriended many of us Dartmouth students. He was a wonderful listener, and therefore a great conversationalist. He could direct the flow quite well. He really enjoyed talking about your interests, as well as about trout and grouse and travel."

Hunting and fishing were front and center in Ford's New Hampshire life, and those who got to know him best were almost exclusively outdoorsmen. Hall took to traveling with Ford during his undergraduate years, visiting some of the storied salmon streams he had heard about while sitting in the living room of the house on North Balch. In 1952 he was on a trip to Alaska with Ford, and they were shooting the breeze in the Red Dog Saloon in Juneau. "We started talking about this fictitious bait-and-bullet society," Hall remembers. Thus was born the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club, whose minutes would grace the pages of Field & Stream for the next decade. Suddenly Jim Hall, an aspirant doctor, was Actively reborn as "Doc" Hall. Sid Hayward became the Club's Cousin Sid.

Every month they'd be sitting around Uncle Perk's Hardware Store the proprietor was Jim Perkins, another '55 passing the jug of Old Stump Blower and chewing tobacco and the fat. "There never really was a Lower Forty Club in life," says Doc Hall, who is now a general practitioner in Medford, Oregon. "But almost all the characters were based on Upper Valley friends of Corey's. Judge Parker was Parker Merrill, whom he'd known for years. Col. Cobb was a kid named Cobby, another Dartmouth student a few years ahead of me. I think by basing the characters on people he knew, the stories were better because, even though they were very funny, they were also true. Those little hunting stories, there is an awful lot in there about human beings."

In the Lower Forty stories, Hanover was reborn as Hardscrabble. As befits a town with that name it was a woodsier, more roughhewn place than the Hanover we know today. The citizenry of Hardscrabble is closer kin to the "Newhart" Larry-Darryl-and-Darryl family than to the Campion crowd that actually trods Main Street in 1990. "But it was definitely Hanover as he saw it back then," Doc Hall assures us. "That's why he called Mink Brook 'Mink Brook' and Moose Mountain 'Moose Mountain.' 'Doc Hall' was what he really called me, in life. It's not that the distinction was blurred for Corey, but just that the stories came out better when he wrote from the truth."

It's Hanover painted by a particularly devilish Norman Rockwell.

I think I'll steal here from myself (for once!) and reissue a metaphor I used in reviewing the Lower Forty stories: "What Lardner was to the diamond, Ford was to the duck blind." That's the kind of cheap-and-easy line you throw in so you'll be among the blurbs on the cover of the paperback. What I failed to say at the time is that Ford, in his Lower Forty minutes, captured a certain upcountry (Upper Valley) type who is dryer, sager, and less a caricature than the Bert-and-I image. The New York Times once said Ford wrote with "grace and truth," and I think that's most applicable to the literature he turned out during the Hanover years.

And, oh yes, the stuff was still very, very funny.

Here's Doc Hall (not the real-world item) discoursing on obstinate game birds: "The only reason I didn't get any birds was because they kept on flying after they were obviously stone dead. For instance, this grouse got up right in front of me and took off across an open field, and I figured out the wind direction and trajectory and rate of climb, and I used my modified barrel with Number Eight chilled which throws a pattern of 29.3 square inches at fifty-five yards, and the only explanation is that the bird didn't know enough to fall." And here's Col. Cobb, on his ever-so-keen bird dog: "I was leading him down the main street of Boston, and he came to a solid point on a total stranger. I knew my dog never made a mistake, so I asked the stranger if he was carrying a bird in his pocket, and the stranger said he wasn't. So I asked him if by any chance he'd been handling a grouse lately, because I never knew my dog to be wrong before, but he said no, he never saw a grouse and he wasn't even a hunter. So I had to apologize for my dog, and I shook hands and said, 'I'm sorry, sir, my name is 'Cobb.' 'Pleased to meet you,' the stranger said. 'My name is Partridge.'"

I remember that when I was a Dartmouth undergrad newly transplanted from Massachusetts in 1971, I overheard similar sly wisdom in the conversation between customer and proprietor at Walt and Ernie's No Shaves, or at the cash register at Dan and Whit's. The College, it seemed to me, was a special place, and not just because of the scenery. Ford felt this way; he was always the students' advocate as well as friend. "A college town is not like other towns," he wrote in My Dog Likes It Here. "Its life changes with the college year. All summer long, when Dartmouth is in recess, Hanover lazes about its local business, and the stores are half-empty, and there is room to park on Main Street; but the place seems empty, a little older and even a little lonely. The townspeople say to each other: 'lt's certainly nice to have a little peace and quiet for a change! But the words echo hollowly, as in a house without furniture." Ford, at least, would have thought well of year-round operation.

"Was he a happy man? I don't think so, no," says Doc Hall—the Medford, Oregon, Doc Hall. "As I say, he was a lonely person and therefore he adopted Dartmouth students as sort of his family. The students made him as happy as he got. He gave a lot of money to the rugby team and became quite a sponsor. And also, Dartmouth had no boxing team, and Corey set up a little gym in the basement of his house and taught the students to box. They established a boxing club. The Jack-O-Lantern had been dormant for several years, and Corey got some students together and revived that—he almost single-handedly re-launched it. Those things made him happy. His mornings were spent writing, his afternoons with the students."

Ford's technical association with the College was more problematical. Ford was a "writer in residence," and such luminaries are supposed to be employed for their expertise and influence. Ford sat in the house on North Balch, eager to help, waiting for the doorbell to ring. It seldom did. "I feel very strongly and somewhat bitterly that Dartmouth did not appreciate him," says Hall. "The English Department was somewhat jealous of him and didn't welcome him at all. Corey contributed mightily to other parts of the College and wanted to contribute here, but they refused him."

For the lucky athletes, humorists and outdoorsmen among Dartmouth students who did avail themselves of Ford's wit, wisdom and friendship, the experience was special.

"I've always felt my most profound advantage in going to Dartmouth was knowing Corey," says Hall. "He was a giant, really. In my opinion Corey was one of the last truly great satirists. He was immensely sophisticated, and some of his friends from Hollywood or New York would come to visit. We all met Edna Ferber once. Gosh, the stories he could tell, as we just sat around! We always asked for W.C. Fields stories those stories were wonderful."

Like the one about how Fields hated birds, and used to take shots at the ducks behind his Toluca Lake mansion with golf balls and a four iron. "The battle grew more and more ruthless," Ford once recalled, much as he must have recalled it for the undergrads. "Once Bill borrowed a canoe and pursued a large swan all over the lake, until he dozed off after his strenuous efforts, and the swan crept up behind the canoe and nipped him from the rear. 'The miscreant fowl broke all the rales of civilized warfare,' he complained later."

Such tales kept students rapt, as they sat and listened to the pipe-smoking old gentleman who once had roared with the twenties. No era is like any other, of course, but Ford's heyday was more singular than most. E.B. White, having breezed through The Time of Laughter, wrote to Frank Sullivan, "I have moments of hoping and dreaming that we will see another Golden Age, or at least Silver Age, when writers will be both gay and disciplined and even when newspapers will show an interest in the litry life. But I dream a lot of things. Anyway, I'm glad I lived when you did, and some others I could mention. It was a privilege while it lasted. Why, it's still a privilege!"

That letter was dated September 13,1967. Two years later, Corey Ford died. Two decades later, White died. Frank Sullivan and James Thurber and Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker well, most all of them have died. Ted Geisel, having breathed more of Hanover's healthy air than even Ford did, lives on.

But then, Dr. Seuss always will, even when Geisel's gone. Seuss will live forever, as will Riddell and Ross, Thurber, White, Benchley, and Ford, too. Their great good humor is as indelible as the ink they used to create it.

Doc Hall tells me that Corey liked to hunt down by Mink Brook, just beneath Moose Mountain. I'm sitting there now. I'm looking down across a snow-covered field that slopes toward Reservoir Number Three. From the back of the pond the wooded hillside climbs to the mountain. It's a cold morning in latest November, and I could swear there's an elderly fellow in a tweed coat tromping through the new snow down by Mink Brook, an English setter at his heel.

Since writers can't take everything with them, they make durable ghosts.

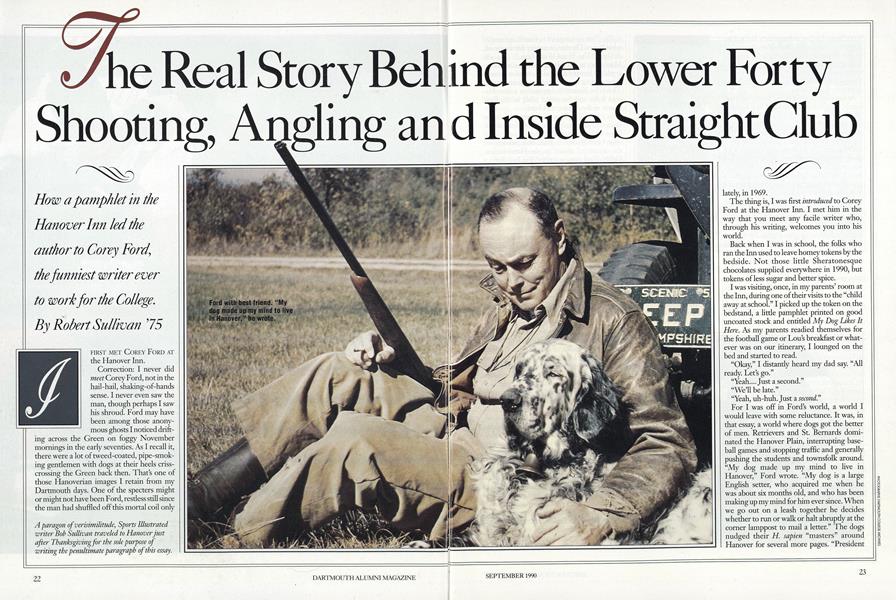

Ford with best friend. "My dog made up my mind to live in Hanover," he wrote.

More best friends. Ford turned collegiate Hanover into the fictional town of Hardscrabble.

Ford with human friends. His circle included such literary stars as Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, and E.B. White.

Ford with rod. Hunting and fishing were front and center in his New Hampshire life.

Ford with Joan Crawford. His many Hollywood connections included the likes of W.C. Fields.

A paragon of verisimilitude, Sports Illustrated writer Bob Sullivan traveled to Hanover just after Thanksgiving for the sole purpose of writing the penultimate paragraph of this essay.

"Retrievers and St. Bernards dominated the Hanover Plain, interrupting baseball games, stopping traffic and generally pushing the students and townsfolk around

"I might've been looking for something by Ford Maddox Ford or maybe nothing in particular, when suddenly a title swam before my eyes (doing Ford would embellish the backstroke)."

"Ford, in his Lower Forty minutes, captured a certain upcountry (Upper Valley) type who is dryer, sager and less a caricature than the Bert-and- I image!"

"Ford satin the house on North Balch, eager to help, waiting for the doorbell to ring."

"Such tales kept students rapt, as they sat and listened to the pipe-smoking old gentleman who once had roared with the twenties

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

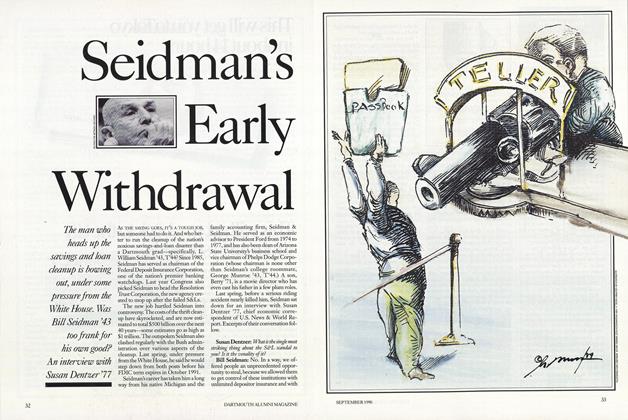

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

September 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

September 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

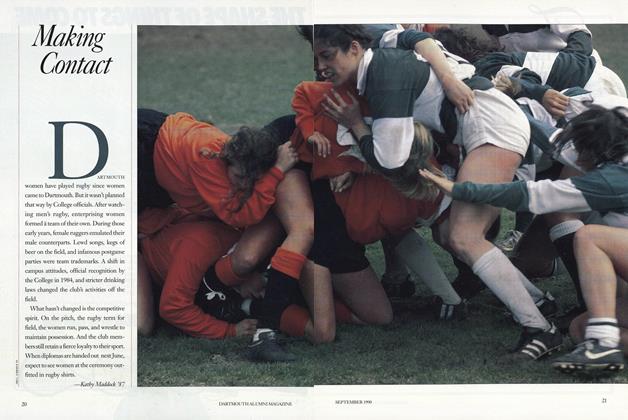

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

ArticleMOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

September 1990 By Professor Marianne Hirsch -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990 -

Class Notes

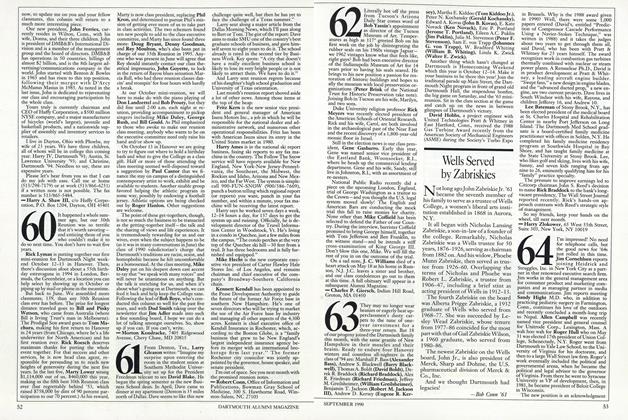

Class Notes1960

September 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsAt the Winter Games

April 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

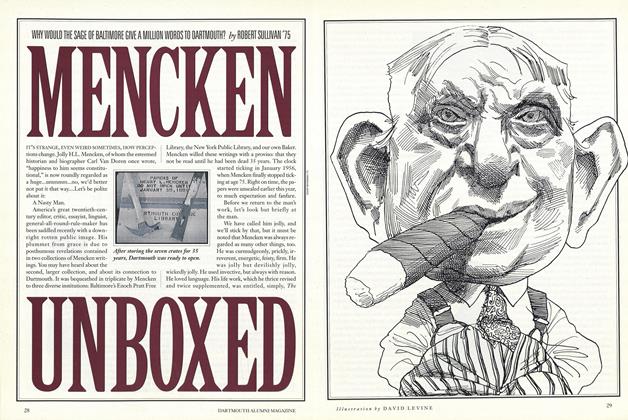

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

OCTOBER 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

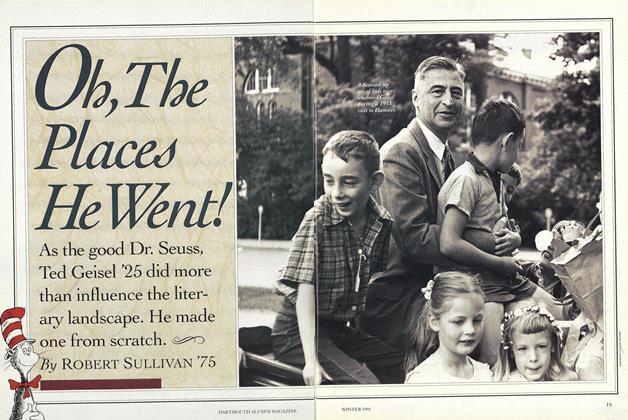

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleFootball From Down Under

December 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

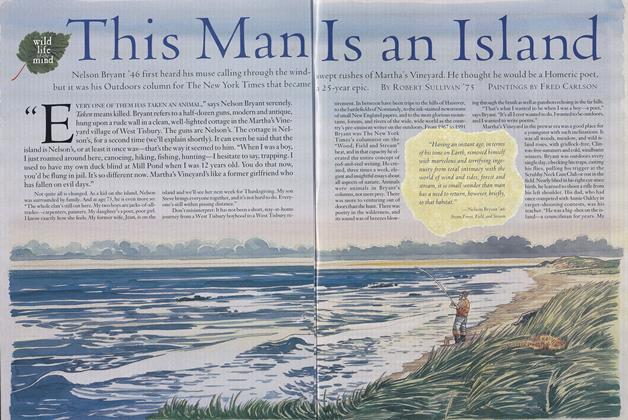

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryPONG PADDLES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

FEBRUARY 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2012 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

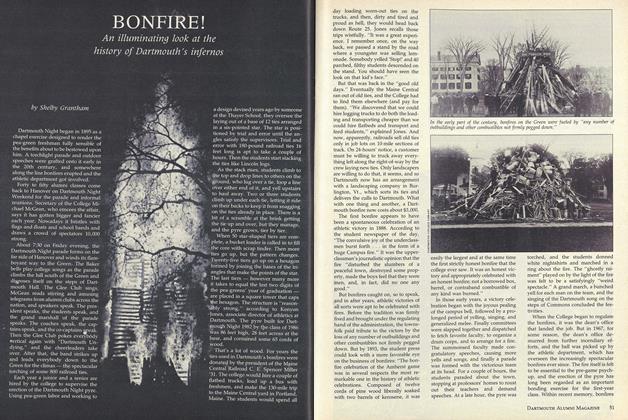

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Sept/Oct 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74