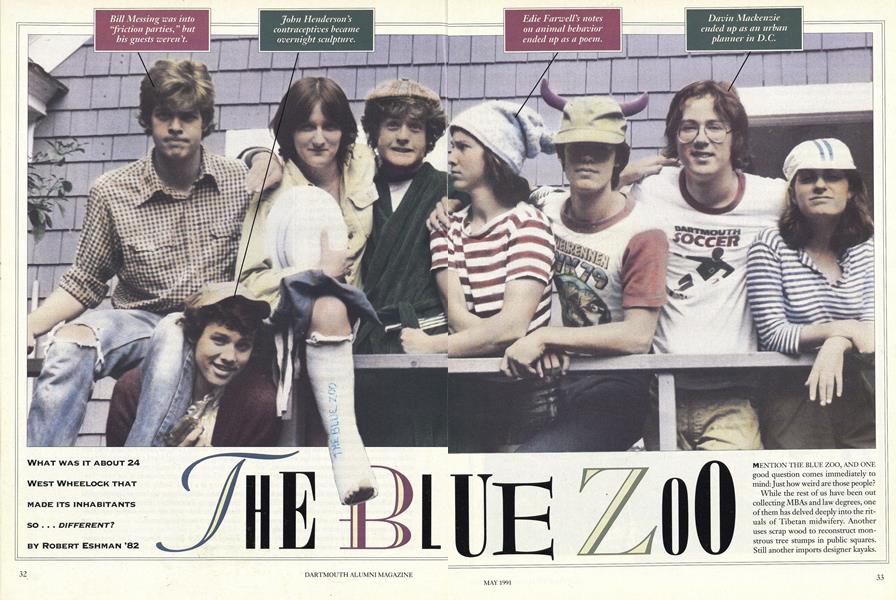

What was it about 24 West Wheelock that MADE ITS INHABITANTS SO . . . DIFFERENT?

MENTION THE BLUE ZOO, AND ONE good question comes immediately to mind: Just how weird are those people?

While the rest of us have been out collecting MB As and law degrees, one of them has delved deeply into the rituals of Tibetan midwifery. Another uses scrap wood to reconstruct monstrous tree stumps in public squares. Still another imports designer kayaks.

And there are at least a dozen more like these. Once they lived together in a chill, cavernous house on West Wheelock Street. Now they ford Afghanistan rivers, succor Indian lepers, assist Woody Allen, and hasten the reign of solar power on earth. Make no mistake: these are not their hobbies, these are their lives.

They are the kind of lives that, not ten years after leaving Hanover, require sighs in the recounting. "Let's see," reflects Peter Heller '82. "I hung out in Putney, Vermont, wrote poetry, moved to Seattle, spent a year traveling and writing. I shot an elk in Wyoming and flash-froze it. It was a trip getting it to Hollywood I couldn't stop the whole way or the thing would thaw out. I worked on a screenplay, found a place in Santa Monica with a woman who turned out to be kind of unsavory. She was a whore. I worked at a lesbian-managed ad agency, writing copy for special resorts, you know, 'The warmth and caring of women among their own...'" Peter sighs. "I went to North Carolina, taught kayaking, and guided trips. Then Colorado, then back to Vermont to do some gardening." Another sigh. "The last couple of years I hooked up with Outside magazine. I did an expedition in the Caucasus white water canoeing in Siberia, treks in western Schezuan province, the Tibetan plateau, the Soviet Pamirs." Sigh. "A year in Costa Rica. Then, oh yeah, my girlfriend and I rode our mountain bikes from Nicaragua to Panama."

Peter is not unusual. There lived in the Blue Zoo about two dozen Peters. Twentyfour and a half, if you count the artist who slept sometimes in the Zoo and sometimes in his studio. But he's an architect now, Harvard '85, and it's hard to say what sets him apart: the fact that he rarely slept at the Zoo, or the fact he attended graduate school.

The rest of them have pretty much avoided the average course of a post-IvyLeague life: graduate schools, professions, the corporate world. The only physician among them, Kim Walsh '82, is finishing her residency at Duke University and plans to work at an inner-city free clinic. "I don't believe in fee-based medicine."

Not one has become a lawyer yet.

There is a mystery to be solved here. There are theories to be tested and disproved, and even a little suspense. "I really like what I do," says Craig Bradley, D'82 BZ '81. And he is not alone. Almost all say, 98 percent of those who lived at the Blue Zoo seem to be engaged by their labors, excited by their lives, and, yes, happy. One hundred percent would say they have not sold out, not abandoned whatever dreams they had then, no matter what earthly forms those dreams have taken. What can account for such amazing, if not scientific, statistics? For all who wonder whither youth, whither ideals, whither joy the answer to the mystery of the Blue Zoo cannot come too soon. Was it something in the house? In the food? In the stars? Was it something indefinable, like a British Columbia accent, or can we tag it, bottle it, and let us pray, sell it?

THE BLUE ZOO: A CULT?

THE NAME ITSELF IS LOST TO History, most likely coined in 1980. Our search for answers begins a bit later, from around the summer of '81 to about the fall of '82. Over this period a total of about two dozen undergraduates would call the house at 24 West Wheelock home.

Assistant Dean Bob Graves, who directs Dartmouth's off-campus housing program, says about 300 enrolled students eight percent live in some sort of off-campus housing any given term. Graves's six years' experience has taught him that many reasons drive students to seek shelter away from fraternities and dorms. Some hunger for a taste of the post-graduation world. Others like the privacy, the increased independence, the chance to cook for oneself. Some just forget to apply for a dorm room on time.

The domiciles vary from single-occupancy flats to cavernous homes where the ghosts of extended New England families have been driven out by the rattle and crash of four, six, 12 students living together. The College owns some of these placesthe Co-op House, for instance, where students take a stab at democratic household management. There's also the International Students House, the Native American House, Fire & Skoal, Foley House, and an "alcohol and substance free house" for students seeking to avoid those temptations.

But the other houses, in Graves's words, "evolve, are handed down," from one group of students to another. These places have no College affiliation and no higher purpose. They do have names, though, and Graves delights in their sound as they roll off his tongue: "The Rock, The Ramp, The Iguana Hut, The Bateau... The Blue Zoo."

Perhaps, goes the first theory, common deprivation can account for the Blue Zoo legacy. "It was cultlike stuff," says Edie Farwell '81, who has since received her master's degree in anthropology. "You don't let people sleep, you feed them weird food, and you freeze them."

The building itself was an oversized footlocker, the color of withering wisteria, wedged up against a birch-covered slope. "It was really blue and really cold, that's all I remember," says one Blue Zoo alum, supporting Farwell's theory. Inside were three floors and eight bedrooms, a small kitchen, and a large, charmless livingroom. The furnishings were dormitory hand-me-downs, or worse.

One fall Jay Mead '82 convinced everyone that the fireplace drew off more heat than it produced, so it was bricked up and left cold. The winter group abandoned Mead's advice. "We held friction parties," Farwell recalls. "We'd invite a bunch of friends over and jump up and down and throw everything we could find into the fireplace." The only visitors who didn't seem to enjoy these parties were two professors from China, guests of Bill Messing '82. Farwell supposes they were put off not by the jumping but by the spontaneous screams that accompanied it.

Others could handle the cold, but not the food.

"I ate things at the Zoo I'd never eaten before, and not much since," says Brad Bradshaw '81. It was Mead who filled the innocent undergraduate stomachs with Japanese Buddhist staples, claiming life's secret lay in balancing the yin and the yang: balls of brown rice stuffed with salted plums, wrapped in violet seaweed; pots of soybean soup, dense with roots and noodles, the color of stewed tree bark; and scrambled tofu, the consistency of sieved mud. There were also bottomless bowls of black bean soup, courtesy of John Henderson '82, and loaves of homemade sourdough bread, set to rise in the water heater closet and baked in the early morning, leaving behind a distinctive cheesy scent. Only during the warm weather of Indian summer did Mead serve regular chili and cold beer arguing that chili was very yin and beer very yang, or vice versa.

In the winter, constant waffles. "We froze to death all night and got up at the crack of dawn to bond heavily over Bill's waffle iron," says Farwell, advancing her preferred Blue Zoo theory. "Sleep wasn't sacred either. At three in the morning, if you wanted to speak with somebody, you just went into their room and sat on them."

A HARMONIC CONVERGENCE?

BUT ARE WEIRD FOOD AND subzero bedrooms enough to account for the offbeat post-Dartmouth lives of Blue Zoo inhabitants? Or was it the Zooites themselves?

"We were all very improbable roommates," Peter Heller recalls. "When I think of the people who lived there, I think of people who were always involved and excited. There was nothing cool about them."

"They were all weird," claims Kim Walsh, "because Peter picked them."

Actually, selection was more complex. Word of the Zoo usually filtered through campus in the week before registration. One student would find the place, then call a friend, who called a friend, who knew somebody else desperate for a room, and so it filled. "We all moved in as strangers and ten weeks later were the best of friends," says Edie Farwell.

By whatever serendipity the Zoo was filled, the people gathered within its walls seemed to be inevitably compatible. "There was incredible harmony," says John Henderson. "The Co-op House had these weekly meetings where they'd sit in a circle and try to work their problems through who didn't rinse his dishes, who left the toothpaste out. We decided we should sit in a circle and see what problems arose. Nothing. We just blanked out, we had to start making up things."

"That was the extremely intangible part of the Blue Zoo," says Brad Bradshaw. "There was a kind of aura around it, an unspoken energy. There never seemed to be any problems between the people."

Not that things couldn't have tensed up. Henderson was conducting contraception road shows for Dick's House at the time, and would often bring his black bag of showand-tell goodies home. In the morning he'd find the contents turned inside out and creatively mounted into a sculpture, diaphragms atop lUDs atop condoms. One evening Edie Farwell mislaid the notes of a field study she had conducted for an animal behavior course. When she awoke, two phantom Blue Zooers had not only found her meticulously gathered and organized observations but had completely rearranged them into a poem.

THE BLUE REFUGE?

BUT ENOUGH OF THEIR ANTICS. Clearly, the Blue Zoo was no Animal House. Phantom poets and friction parties fully clothed were the extent of its savage abandon. If the Zoo was not a place where the animals could run rampant, what was it? And how was it that the Zoo sent so many square pegs into society's round holes? To return to Dean Graves, "There are those students who don't fit in and want to. And there are those who don't fit in, and don't want to."

And these students sought refuge on West Wheelock. Many breeds maladapted to mainstream Dartmouth life found in the Zoo a more suitable habitat. There, they thrived.

"My class saw the beginning of changes at Dartmouth, a real turn to the right," says Landis Arnold '82, echoing the sentiments of most of his housemates. "As that went on I disliked the mainstream more and more. At the Blue Zoo nobody got on your nerves. Everything was more spontaneous and easy It was the first time I had comfortable autonomy."

Jay Mead describes the Zoo as "an establishment of the fringe." Along with many Zooites, he says he was ready to leave Dartmouth after freshman year. "If I had only seen the typical Dartmouth, I couldn't have survived there. Fortunately, I ran into these great people."

"Freshman year there's a lot of fear you'll never find your pocket," adds Bradshaw, "but then we did find the Blue Zoo."

Henderson calls the Zoo "a fringe that was still part of the fabric." He and the others remained active in College life but inevitably beat a path back to the Zoo. "It took a while to find people who you like," says Henderson. "By junior year we found them, and that saved us. Some people never found it."

The Zoo, then, became their watering hole, safe house, haven. "We were on the periphery socially but quite committed in other ways," says Craig Bradley. "None of us wanted to hold on to the Dartmouth social norm."

Bradley has had special reason to wax analytical about the Zoo. After graduation, he worked for a while with Procter & Gamble, marketing laundry soap. He grew miserable fast, quit, and found himself back at Dartmouth, this time as assistant dean. Now as dean of students at Kenyon College, he says he has often wondered if there's any way a college can institutionalize a place like the Zoo. His conclusion: yes and no. "There can be more social options. A college can at least make space for people who want to live together. But the Co-op House was an attempt to have what we had in reality at the Zoo. So who knows?"

THE BLUE ZOO:SUPERFLUOUS?

BRADLEY HAS HIS OWN THEORY about how his fellow housemates carried their odd, Blue Zooian lives into the fabled real world. "It was a self-selecting bunch," he says. "People at the Zoo were willing to be themselves and be honest with themselves. They weren't pretending. If you carry that beyond college you end up making good choices. Working in corporate America was totally incompatible with who I am. Life in the Zoo had a common theme the people there thought for themselves and have continued to do so. That makes a difference in how happy you are after Dartmouth."

So what blasphemy is Dean Bradley speaking? That these students' strange fates were sealed even before they set foot in the Zoo? That the Zoo did not create these odd personalities, merely harbored them? That none of it the freezing cold, the gruesome macrobiotics, the mysterious harmony none of this really matters? That Landis Arnold still would have left Olympic ski jumping to become a Boulder-based importer of highquality German kayaks? John Henderson would have still gone from working with Cambodian refugees and Indian lepers to teaching elementary school in Seattle? Peter Heller would still have piled adventure on top of adventure, eventually collecting them in his soon-to-be-published book, Set Free inChina, and Other Stories of a Wilderness Traveler? And would he still be summing up his future goals in one word "flyfishing"?

And the rest, what about the rest? Kim Walsh is about to hang her medical diploma on the wall of some inner-city free clinic. Edie Farwell's book on Tibetan midwifery is just now wending its way to publishers. Last summer, the City of San Francisco awarded artist Jay Mead $1,500 to recreate the stump of an old-growth redwood out of cast-off scrapwood. Mead built it 20 feet tall, 15 feet around in front of City Hall.

Brad Bradshaw, an expert on alternative energy, works for DMC Enterprises, advising power companies on how they can improve the energy efficiency of their consumers. Chris Colt '82 is in New York, acting, making the rent as a production assistant for Woody Allen.

There are other Blue Zoo alums with similar fates teaching, writing, selling camping gear, working for non-profits. Bradley would have us believe that they too would be doing the exact same uncommon tasks even had they not passed through the Zoo. That perhaps the truly remarkable fact was not where they lived while at College, but that Dartmouth was broad-minded enough to admit them in the first place.

Perhaps. One way to test Bradley's theory would be to send a student intern from Dartmouth Alumni Magazine down to 24 West Wheelock. He could knock on the door and see what harmonious, aura-ridden pack of fringe-dwellers swings it open. But what would that prove? If the light shone from the Blue Zoo in '82, maybe these days it's taken up at a different address. "Maybe Dartmouth just lends itself to this," says Brad Bradshaw. "There are pockets of diversity. Maybe the Blue Zoo happens every year."

Maybe it does. And whatever this year's Zoo is called, it will give its residents the same sense that at a place as seemingly normal as Dartmouth, it's fine to be just a little off. The new Zoo will prepare them for their future selves by making them secure with their present ones. Most importandy, it will not easily forgive any apathy and compromise. "The energy we felt at the Blue Zoo was something we wanted to remain in our lives," says Jay Mead. "If we lose that energy, that means we're getting old.

A FINAL WARNING

MEAD RECENTLY MARRIED, HE donned an Indian dhoti, climbed into a canoe, and set out across a Minnesota lake. On the other shore, he met his bride Edie Farwell. She arrived in a canoe paddled by her father. A Tibetan monk and a Protestant minister performed the ceremony. Seven former Blue Zooers were in attendance.

In fact, in the summer and early fall of this year, Jay Mead, Edie Farwell, Kim Walsh, and Bill Messing all Blue Zoo graduates have all married. This article then arrives with fair warning. Whatever mystery the Blue Zoo inhabitants contain, there is also this fact: they breed.

Bill Messing was into"friction patties," buthis guests weren't.

John Henderson 'S contraceptives becameovernight sculpture.

Eclie FarwelVs noteson animal behaviorended up as a poem.

Davin Mackenzieended up as an urbanplanner in D. C.

Arrving by canoe,Edie Farwell had aTibetan monk marryher to Jay Mead.

The only Blue Zoodoctor; Kim Walshplans to work in aninner-city free clinic.

Craig Bradley quitmarketing laundrysoap and took upa career in deaning.

Jay Mead got agrant to recreate aredwood stumpout of scrapwood

Before mountainbiking to Panama,Peter Heller wentyakking in Tibet.

"It wascultlike stuff.You don't letpeople sleep,youfeedthem weirdfood and youfreeze them."

There is amystery to besolved here.There aretheories to betested anddisproved.

Mead arguedthat chili wasvery yin andbeer very yang,or vice versa.

"MaybeDartmouthjust lends itselfto this. Thereare pockets ofdiversity.May be theBlue Zoohappensevery year."

Robert Eshman '82, though an alumnus of theBlue Zoo, has never hiked the Soviet Pamirs,studied Tibetan birth practices, or helped lepers.He is a free-lance writer yawn in Los Angeles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

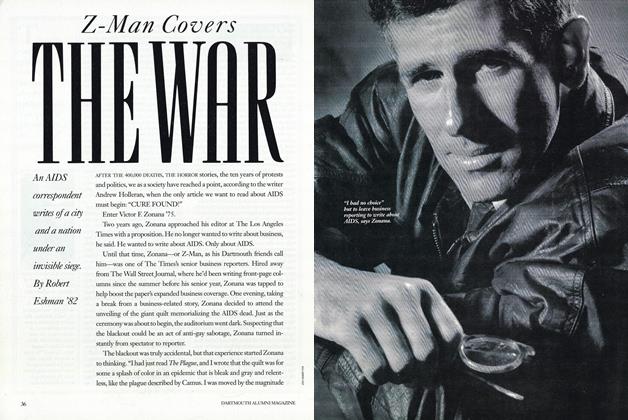

Cover Story

Cover StoryDOCTOR WENNBERG'S UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

May 1991 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

FeatureStory Time

May 1991 By Nancy Millichap Davies -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

May 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleTHEATERS OF WAR

May 1991 By Professor Lynda Boose -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1991 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Robert Eshman '82

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2012 By Jay Mead '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

NOVEMBER 1998 By Rebecca Bailey -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHer Type

MARCH 1995 By Susan Ackerman '80