"In a single ringing sentence, Justice Black reproached and redeemedhispast.

In his 1972 gathering of esays, Sincerity and Authenticity, Lionel Trilling quotes a plaintive query by the eighteenth-century poet Edward Young: "Born Originals," Young asks, "how comes it to pass that we die Copies?" Let me tell you about two "Originals" who broke Young's mold: Hugo Lafayette Black and Martin Luther King Jr.

Hugo Black was born in a small wooden farmhouse in the Appalachian foothills of Clay County, Alabama, in 1886, the youngest of eight children. He died in 1971 in Washington, D.C., where he had served 11 years as a United States Senator and 35 years as a Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Hugo Black's secret, revealed only after his confirmation, was that his path to Washington had led, briefly, through the dark swamp of the Ku Klux Klan.As a young trial lawyer in Birmingham, Black had joined the Klan in 1923 out of a tangle of motives, including the desire to strengthen his hand before the Klan-dominated juries of the time. It is now clear that his judicial career was a sustained attempt to rectify this error.

In 1940, three years after ascending to the Court, Justice Black wrote Chambers v. Florida, overturning the convictions of four impoverished black tenant farmers who, without benefit of counsel and after nine days and nights of relentless police questioning, had confessed to a murder. In a single ringing sentence, Justice Black reproached and redeemed his past: "Under our constitutional system, courts stand against any winds that blow as havens of refuge for those who might otherwise suffer because they are helpless, weak, outnumbered, or because they are non-conforming victims of prejudice and public excitement."

Hugo Black was a man of scant formal education, but he pursued a personal course of reading and self-education probably unprecedented in the Court's history. He immersed himself in history, economics, and philosophy, slowly becoming one of the rare judges with a constitutional philosophy.

A vigorously public man, he disciplined himself to cultivate his private self. As one of his law clerks recalled, Justice Black was always "on Mount Olympus, communing with the Constitution."

The life of my second exemplar, Martin Luther King Jr., is a tale of the steady maturation of his religious faith and his moral philosophy, to the elevating point of his perception, in Let-ter from the Birmingham Jail, that "injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere."

Instead of attending a conservative Southern Baptist institution devoted to the preparation of black ministers for southern pulpits, King chose to attend Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. As he matched wits with his free-thinking professors (some of whom were agnostics), he began to form his own philosophical positions and thought of a career as a professor of theology. Instead of returning to the South to preach, he entered Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D.

Facing the need to support his growing family while completing his dissertation, King decided to gain some experience as a pastor after all. At 26, he won the prestigious pulpit of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery in 1954, just two weeks before Brown v. Board of Education was decided and only a few months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus.

By the time Dr. King was assassinated in April 1968, he had broadened his witness on behalf of blacks to include the poor and all oppressed minorities; he had extended his political agenda to take in economic as well as racial issues; he had expanded his moral vision to embrace the cause of peace as well as of social justice. And yet, even when his public life must have seemed all-consuming, Martin Luther King Jr. found the moral and intellectual reserves to continue to cultivate a private self of philosophic contemplation.

And so I return to Edward Young's question. The two exemplars from my own development were born "Originals," as each of us was. By their unusual capacities to know who they truly were and by their remarkable abilities to grow in understanding and expression, they kept the trivializing tendencies toward social and intellectual conformity from reducing them to "Copies."

As today's students ask themselves what kind of persons they want to be, I hope they will find heroes and heroines of their own—men and women who will inspire them to grow through experience, to choose goals worthy of their talents, to nurture the development of their private selves, and to take their own places as "Originals." m

This essay is adapted from the president'sConvocation address, which he deliveredlast September.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

June 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

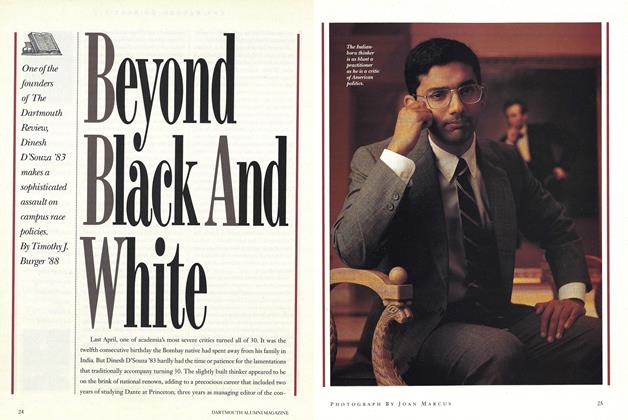

FeatureBeyond Black And White

June 1991 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

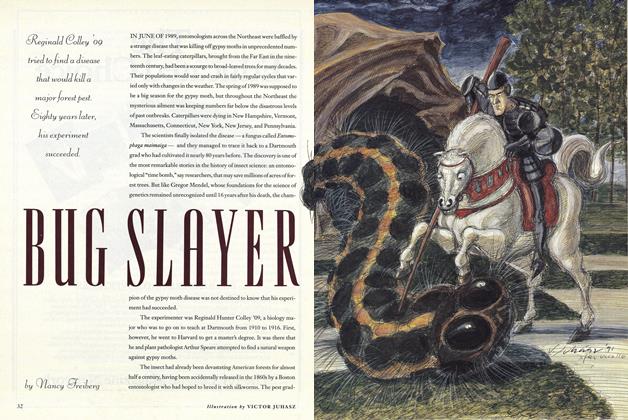

FeatureBUG SLAYER

June 1991 By Nancy Freiberg -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

June 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleCOMPUTING AND THE RING OF INVISIBILITY

June 1991 By Professor James Moor, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Awards

June 1991

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleTHE PASSIONS OF SCIENCE

December 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE SENSE OF PLACE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleAdvancing the Human Condition

NOVEMBER 1993 By James O. Freedman