AN DN-CAWIPUS SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THIS MAGAZINE ASKED: WHAT'S SO FUNNY?

It is not humor to be malignant.

LATIN PROVERB

WE SIX GATHERED IN HANOVER FOR A FUNNY REASON. We were there for what was hoped would be a fruitful discussion. We six had been gathered, under the grandiloquent auspices of "A Dartmouth Alumni Magazine Symposium," to investigate one salient question of our times: Is Humor Still Possible?

Well, actually, two of us wouldn't be doing any investigating. Jay Heinrichs, the magazine's editor, would be doing a bit of moderating. And I would be doing some... I hesitate to say "chronicling." That's simply too highfalutin. I would be, shall we say, taking the minutes.

This, then, is the secretary's report.

At a pre-symposium dinner, our four investigators—call them panelistsseemed happy if mildly trepiditious about taking part. The quartet included Annelise Orleck, assistant professor of history at the College who just then was preparing an article for the jour- nal Feminist Studies on what I believe is the seriously non-comic subject of "militant housewives"; John Watanabe, assistant professor of anthropology at Dartmouth who is not only expert on counterinsurgency warfare among Guatemala's Mayan population but also on the social relationships and ritualized greetings of adult male baboons; Steve Kelley '81, the standup comic whose day job is as editorial cartoonist for the San Diego Union and whose heritage includes a founding role in The Dartmouth Review; and Regina Barreca '79, associate professor of English at the University of Connecticut and author of the lively, witty, altogether terrific book about women-in-humor, They Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted.

We sat 'round a table at the Hanover Inn, behaving much like Watanabe's baboons: There was a lot of ritualized greeting going on. As we chewed the chicken, chewed the fat, and chewed the question of the hour, it became clear that a relevant conundrum was inherent in the proverb that heads this report. Our ancient Latin proverablist (or proverbial Latin?) posited: It is not humor to be malignant. Indeed? Is it not? Is malignancy always without humor? Is it really malignancy—and not humor that the culture police of the nineties are warring against? Perhaps there's no assault on comedy at all, just upon mean-spiritednrss going about in comic guise.

Ah! We were ready. We adjourned, totally perplexed, to Cook Auditorium. There, surely, a packed house of eager students awaited our expert panel.

fell, Cook wasn't quite packed, but there was a very respectable (I hope!) crowd on hand (a few straggling students arriving late, as students will).

Moderator Heinrichs succinctly introduced the subject: "Many students these days seem leery of telling jokes outside their immediate social circles for fear of offending someone... In these sensitive times, we have to ask the question: Is everything sacred? Has our sensitivity for the feelings of others turned into hypersensitivity? Are we moral hypochondriacs, constantly on guard against jokes that might hurt us? Or is PC just a reflection of an evolving national taste?"

The comic Kelley started things off. He had brought, as the smart panelist does, visual aids. These were some of his cartoons from the Union, with points-of-view that might be considered touchy. One favorite of ours: "Famous Quotes from the Kennedy family." In panel one JFK was demanding forcefully, "Ask not what your country can do for y0u..." In panel two Bobby was delivering his noble "I see things that never were" address. And in panel three a bloated Teddy, drink in hand, leer in place, asked, "Come here often?"

Now, you say: The Kennedys can take it. They're public figures, they're fair game. The libel laws apply.

Maybe for the San Diego Union they do. But consider that when the Dartmouth band performed a Teddy-roasting at halftime a few years ago—com- plete with Chappaquiddick swimming events and even more questionable stuff—the hammer came down, and hard. The band was censured and censored and boxed about the ears. We, the Dartmouth community, were compelled to apologize to Holy Cross. I mean, Yucch!

Point being: Things are different on campus. Should they be?

"Well, that's a difficult one," said the thoughtful Prof. Watanabe. "College isn't just any institution. We're educating here. The students are adults, but they're also still kids, and still learning. And so, perhaps they're being taught sensitivity. They're also being taught what emotional violence can be done to their friends and peers."

aid Prof. Orleck, "What is funny is very much in the ears of the listener." Good point, and others immediately seized upon it.

"You have to know what's funny in order to laugh, and in order to know what's funny, you have to know what's not fanny."

For instance (all the panelists were ready to shout): ANDREW DICE CLAY.

The Diceman, for those of you in the class of aught-three who don't know, is not a nice man. He's a vile, reprehensible, racist, sexist, greasy man, and he's proud of it. He's also a rich man, because his audience, consisting in large part of teenage boys, has given him their allowance money in return for jokes like, "Foreplay? You want foreplay? Didn't I slap you around for half an hour?" and like "They should have a sign at the airport: if you don't know the language, get the **** out."

The Diceman provided a good flashpoint at the symposium because he's current, he's hot (though cooling) and he's well-known to college kids. He works often on college campuses, and this proves perplexing to some. As John Leo wrote in a U.S. News and World Report essay, "What sense does it make to consider expulsion for one student who said in class, 'Someday, it might be possible to cure homosexuals,' while Clay is at the microphone violently stirring up campus yahoos with faggot jokes?" Another good question.

(As a brief aside, I might mention here that the considered expulsion was of a University of Michigan student, who was called before a disciplinary committee for violating school rules against speech that "victimizes" people due to their "sexual orientation." In 1989 a district court ruled that Michigan's stricture violated the First Amendment. We'll return shortly to the question of what colleges can and can't, should or shouldn't do in trying to regulate taste, speech bias, and humor.)

It seemed that no one on the panel thought the Diceman was fanny, and no one would defend much more than his right to exist. But he was useful as the discussion shifted to standards, and to this question of what's not funny.

What's funny differs from culture to culture," said Prof. Watanabe.

And from sex to sex, Prof. Barreca pointed out. "Women hate the Three Stooges," she said, enlightening me and I hope several others. "And they don't think the fart scene in 'Blazing Saddles' is fanny. And guys don't understand why they don't."

Not only in different cultures, said Prof. Watanabe, "but in different parts of the world and different ages. The Guatemalan Indians of ages past were not interested in self-deprecation in their humor. They were into victim humor. They made fun of each other—oddities, deformities. There were cripple jokes among the Mayans. And there was no community sanction against this; it was expected." The Mayans, then, might be thought of as this self- contained unit of Clays—a (shudder) Dice Clay planet. They would hazard arrest were they to strut their stuff before the nineties culture fuzz.

Or, for that matter, before any right-thinking, civilized, person. The panelists were closing in on this point: That since standards aren't laws, they do not comfortably submit to across-the-board legalistic interpretations. Standards, to paraphrase Prof. Orleck on humor, are in the conscience of the beholder.

Are some people too sensitive about humor? The comic Kelley thought so, and I think he might be right. "It seems nobody can take a joke anymore," he said. "People see hidden agendas in everything, and people are always rushing to protect perceived victims, whether or not the victims ask for protection."

That certainly happens on college campuses. On campus...well, our next epigram serves nicely:

Yes, on campus sharp wits often cut their own fingers...or whatever. We already know of all the Review's efforts at being funny, and all the various trouble that ensued, and so, if you please, I'll not review the Review's laundry list of offenses again. But here are some other interesting cases:

In 1987 University of Connecticut football players harassed eight Asian-Americans by singing "we all live in a yellow submarine."

In recent years JAP-bashing—the ridiculing of Jewish American Princesses, which used to be decidedly mild in tenor—has gotten ugly at Boston University, Syracuse and elsewhere. A typical newwave JAP joke goes like this: "What do you call 49 JAPs floating face down in a river?" "A beginning."

In 1989 an electronic, bi-coastal brouhaha erupted when Stanford, after receiving complaints from MIT, ordered its Computer Science Department to expunge a "joke file" in its UNIX system. An MIT grad student had been offended upon uploading this joke: "A Scotsman and a Jew are having dinner in a restaurant. When the waiter brings the bill, the Scotsman says, 'I'll take it,' and he does. Next morning this headline appears in the local newspaper: JEWISH VENTRILOQUIST FOUND MURDERED IN A BLIND ALLEY." FYI: MIT complained of antisemitism, not Scot-bashing.

Last year the Dartmouth humor magazine the Jack-O-Lantern was threatened with suspension after several admittedly offensive articles appeared in its summer issue.

How do we handle such incidents? How do the colleges handle them?

Sometimes, by panicking. Did Stanford's administration try out that joke before signing its death warrant? Doesn't it seem like there was some fraternal appeasement of MIT behind that knee-jerk censorship? It's not only a pretty mild joke, it's a pretty funny one. Perhaps it goes to show that we're all in a quandary about this situation these days.

At other schools, there's an increasing tendency to institute speech-cleansing rules such as those that used to exist at Michigan. These new bylaws may or may not be struck down by the courts, as Michigan's were. U-Conn has such rules now; Dartmouth does not. The American Civil Liberties Union thinks all such rules are unconstitutional and heinous, and other libertarians agree. The colleges tend to use Watanabean arguments: "We're not just any institution here. We're in the business of educating kids, molding their ethical sensibilities, teaching them not only legal and illegal, but right and wrong, and good and bad."

You might be interested to learn that the Jacko is on-line again, having selected, under pressure, new officers, editors and advisors. The deposed have learned:

the conversation at the sympo sium kept coming back to one tenet: That different standards of humor, dress, anything at all—apply in different cultures, and that ours is an evolving culture, as are all of them, as will they all be in the future. Furthermore, a college culture is as different from, say, a stag-party-when's-the-stripper-arrive? culture as a stag party is from a watch-Stooges-videos party as a Stooges party is from the ancient Mayans. (Well, maybe the last two are kin, but you get the point.) In other words, the Diceman can play Spaulding Auditorium and he can play Caesar's Palace, but he cannot play the Rose Room at the Algonquin, even though all three venues are in the United States of America, the greatest democracy ever invented.

Listening to the conversation hover about this point, I started jotting some notes. "Let's," I wrote, "establish a theorem: Dice is OAJ." To explain, OAJ stands for "obviously a jerk," and I was figuring Dice Clay was OAJ anywhere but in the privacy of a pimply teenage boy's bedroom or as the warmup at a Slayer concert. That's clear to everyone, right? So what we have here is some few sub-cultures where the Diceman is okay.

Ted Kennedy jokes? Seemingly okay in all cultures, save halftimes of college football matches.

Charles Manson jokes? Fine for all; no sympathy for the devil.

Ah, okay—l sensed a conclusion coming. There are places where certain jokes play well or poorly. And this shows the way humor survives or dies within various cultures. Cruel jokes, which were de rigueur for Watanabe's Indians, would be verboten—they would lead to shunning—at Fifth Avenue cocktail parties.

We're getting close, here. We understand how and why various cultures define humor.

But all of a sudden it dawned on me: Mayan Indians. Ancient Mayan Indians!

There was humor way back then? Well, pardner, I'll bet they had the same problems with it that we're having!

You can see, perhaps, that I've been playing a game with these epigrams throughout this report, a game besides one that has already allowed me to avoid making a half-dozen perhaps tricky transitions. The game has been to show complainants from many an age, displayed in a scrambled chronology, expostulating upon this question of whether humor is still possible. The game's riddle: Is our current debate anything new? Have affairs been ever thus?

Look, but briefly, at the fluctuations of what constituted humor in a much earlier age. Look, for just a moment, not at Watanabe's Guatemala, but at ancient Greece—the cradle of civilization, the womb from which our western sensitivity was delivered.

For this glimpse, I thank Prof. Philip H. Young, director of the Krannert Memorial Library at the University of Indianapolis. He was not at the symposium but is author of a paper, "Fighting in the Shade: What the Ancient Greeks Knew About Humor." Young points out that the Greeks gave western civ not only our political, literary, linguistic, artistic, and architectural traditions but also invented formal comedy and have lent us our general "sense" of humor. He writes, "Athenian comedy (meaning literally "singing in a komos" or happy, drunken procession) was probably born out of the festive dancing and satyr plays associated with the Dionysos festival. In the latter, actors wore costumes with heavy padding in the stomach, phallic, and buttock areas to represent the half-human satyrs thought to be associated with Dionysiac revel. These merry dancers, called 'komasts' in Attica, are frequently represented on sixthcentury B.C. pottery, slapping and kicking their buttocks and dancing with women."

The first toga party! When I read that description, I saw Belushi.

So the point is made that there was comedy back then. But did they wrestle over what was comedy?

Yes, they did. Plato, as his above epigram implies, thought humor wholly malicious, an unacceptable ridiculing of others less fortunate. He was like a college dean. But Plato's teacher, Socrates, routinely made fun of those who were impotent. Socrates, in turn, was himself ridiculed. "Probably the best-known example of Aristophanes' use of insuit humor is the portrayal in the 'Clouds'," writes Young, "a characterization so funny and yet so accurate that it is reported that when the play was originally presented (433 B.C.) Socrates himself, one of the spectators, stood up and bowed to the audience."

And then, eventually, came Plato's pupil, Aristode. He basically sided with Plato, arguing that comic writers used slander and falsehood, and always made fun of the unfortunate.

Maybe Socrates had a different, perhaps a "better" sense of humor than did Plato and Aristotle. Maybe he was less thin-skinned. Or maybe, back in the fifth-century B.C., the mores of the people shifted slightly in those few decades. Perhaps the standards were impacted by the newer philosophers, the latest arbiters of good taste.

Let's leave Greece. Look at England. Shakespeare wrote famously bawdy poetry—lusty, downright dirty. Plus, his plays were fall of (then) perfectly acceptable Welsh jokes.

A couple hundred years later, with Victoria on the throne, a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking. Circumspection was all!

And then, another century on, heaven knows, anything goes! Monty Python had all sorts of fun with the handicapped—the disabled, for goodness sakes—in its Twit-of-the-year routine. The Mayans' revenge!

Now, you argue: Yeah, maybe, but those cultures never had Dice Clay. Things were never as bad as now.

Oh no?

Back to Greece. According to Young, "Aristophanes' comedies are filled with explicit terms for intimate body parts and functions which are often toned down or omitted in modern translations." Young also points out that "Greek vase painters found humor in many subjects. In one sexual scene a loving couple risks burning their genitals as they recline towards a long-since forgotten oil lamp." The Diceman's got nothin' on that potter.

So then, be it resolved: Ever thus, it's ever been thus.

But with that resolution, something else started bugging me. Why, if it's been ever thus, did we hold this symposium now, in the nineties? Why did we gather to discuss Is Humor Still Possible today? This whole controversy simply must be more pressing than it has been, at least in the recent past. Right?

Life is so **** serious all of a sudden," said Dan Jenkins, one of two modern purveyors of humor I called subsequent to the symposium. Jenkins is author of the bestselling Semi-Tough in the seventies and of the more recent YouGotta Play Tough, from which the Jenkins epigram came. "Maybe it's because people are getting hurt now—by society and so forth—and are really defensive. It's strange times, it's weird. Because on the other hand, while my agent's telling me I've got too many ****s in my book, they can do anything they want over on the cable-TV channels."

"There's still a whole lot of freedom," says Roy Blount, another professional purveyor of humor whose own latest book is called Camels Are Easy, Comedy'sHard. "Look at cable TV, look at that guy Andrew Dice Clay. Half of the male standup comedians I see on 'Evening at the Improv' just do that angry backlash- against-women stuff. Their humor is much more likely to be offensive than funny. Now, when it's impossible to give offense by what you say, it's almost impossible to be funny. But there's a difference, certainly, between humor and offensiveness. They're two different things, and it's telling them apart that's sometimes hard."

"I always thought humor was the way to cure things," said Dan. "****."

"There's always changing standards of offensiveness," said Roy. "It's confusing."

Here I interrupted. I said, Yeah, in fact, Socrates made jokes about impotency and Plato would have none of it.

"Maybe Plato was impotent," said Roy, "and Socrates wasn't."

As wrapped up, I found that the panel was rooting for humor. They wanted the answer to be, yes, Humor Is Still Possible. They were, after all, human, and as the British poet-statesman ("poet-states-man"! Only in England!) of the six- teenth-century Sir Fulke Greville said in a not-already- used-up epigram: "Man is the only creature endowed with the power of laughter." Man—or any animal—wants to exercise all his powers. He wants to find a way to laugh.

Said Prof. Barreca: "There's room for humor as long as there's not a bully around, someone who says, 'You've got to find it funny because I say it's funny.' It comes down to whether we laugh out of rage or fear. It's finally not as dangerous to say, 'You shouldn't find it fanny because it degrades peo- ple.' Instead of what we've heard all along: 'You must find this fanny, even if it degrades you.'"

Good point. And Prof. Watanabe had an elaboration on it: "What has changed is not so much our sense of humor, but the social context. For instance, we have less control over who hears what we do or say because of the media. We ask ourselves constantly, because of this, things that earlier societies didn't have to ask: Who are we telling jokes to, and why? I think these are good questions to be asking ourselves."

Fine. So all we're left with is: Is Humor Still Possible?

The Answer, by Prof. Barreca: "Yes, it is. Will we laugh at the same things? No." She implied that the world would be better for this. Your 'umble secretary hopes and believes she's right. I hope and believe this, even though I suspect she means that we'll not be laughing at the Stooges together anymore. I hope and believe this because, well, we need humor, don't we?

Our group repaired once more to the Hanover Inn, this time to the Ivy Grill. We chose a table way in the back. Back there, cocooned, unheard by others, we munched trail mix and sipped cocktails and celebrated what we considered to have been a pretty good and entertaining symposium. I have since learned from preparing for this essay that a "symposium" was a men-only drinking party in ancient Greek society. I wish I'd known that then. Prof. Barreca would've got a kick out of that. She likes a good joke.

So, anyways, we frail humans sat there, in an isolated culture, and chattered. Things devolved. Pretty soon, we were telling Jeffrey Dahmer jokes. We were laughing our heads off.

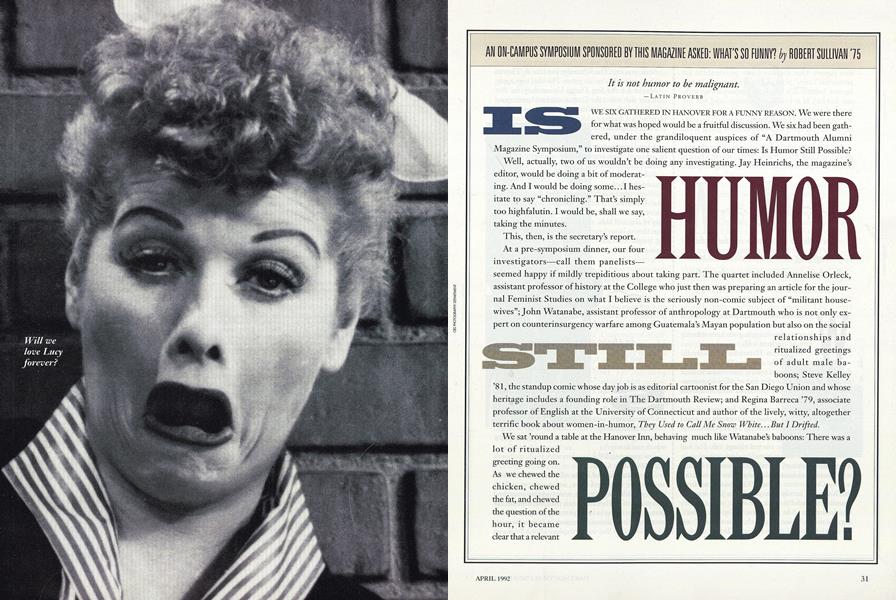

Will welove Lucyforever?

There is no man who in the habitof laughing at another does not missthe virtue and earnestness altogether. PLATO, MORALS COP, FIFTH CENTURY B. C.

Satire will always be unpleasantto those who deserve it. THOMAS SHAD WELL, ENGLISH POET, DRAMATIST AND ALL-ROUND BARD-ENVIER, SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

The Diceman's emanationsappeal to the acne'd set.

Avoid witticisms at theexpense of others. HORACE MANN, NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN SCHOOLMARM

Dice had soulmates inancient Mayans.

Sharp wits, like sharp knives, dooften cut their owners' fingers. AARON ARROWSMITH, VERY SHARP LATE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH GEOGRAPHER

A joke's a very serious thing. CHARLES CHURCHILL, EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH JOKEMEISTER

People who do not knowhow to laugh are always pompousand self-conceited. WILLIAM MAKEPEACE THACKERY, EXTREMELY HUMBLE AND MODEST BRITISH WRITER, NINETEENTH CENTURY

Ancient toga-partiers likeAristophanes coined comedy.

But if you really want to know what**** me off, it's the fact that anycareless remark or innocent remark or,God forbid, humorous remark, writtenor spoken, can be punished bychicken**** boycotts or lawsuits.We are seriously doomed. DAN JENKINS, FUNNY NOVELIST AND SPORTSWRITER, 1991

Jesters do often prove prophets. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY BRITISH BIT ACTOR

Roy Blount may know whyPlato hated impotency jokes.

Man alone suffers so excruciatinglyin the world that he was compelledto invent laughter. NIETZSCHE, NOTABLY SPOIL-SPORTISH GERMAN PHILOSOPHER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

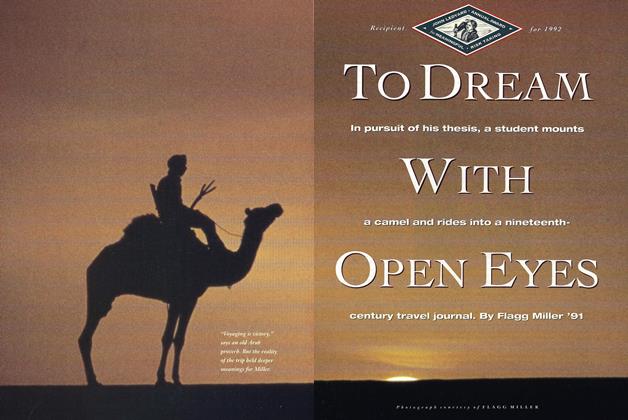

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

April 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

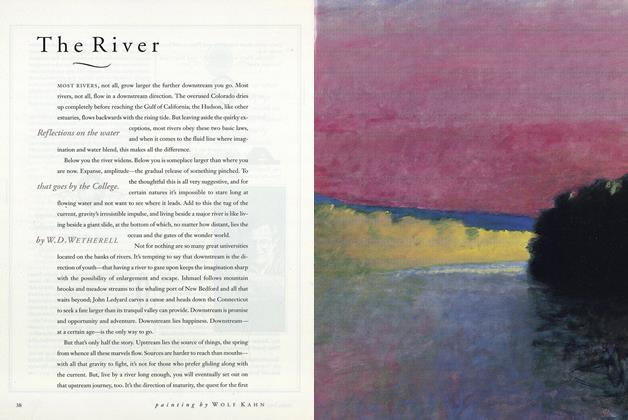

FeatureThe River

April 1992 By W. D. Wetherell -

Feature

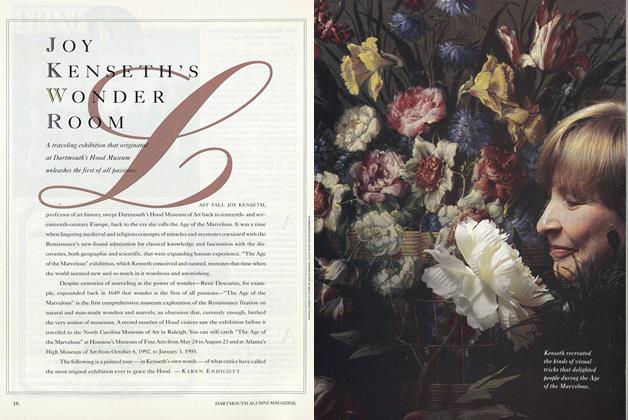

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

April 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

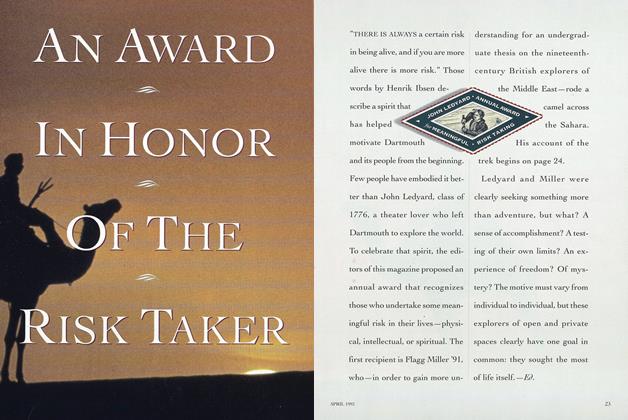

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

April 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Imagination Unbound

April 1992 By Ulrike Rainer -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

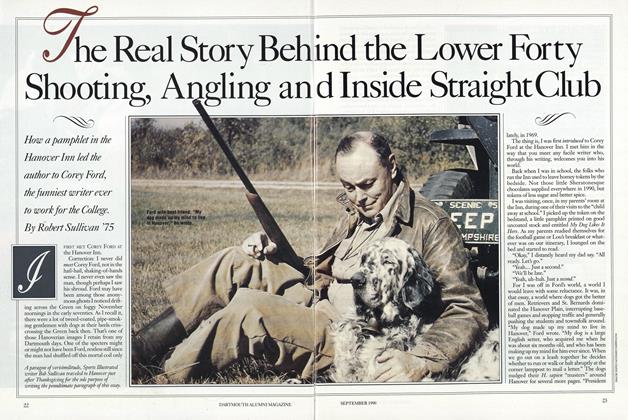

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

MARCH 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Off-Broadway

SEPTEMBER 1997 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

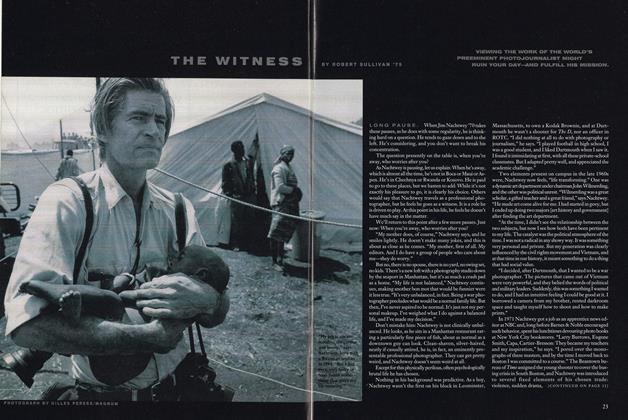

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

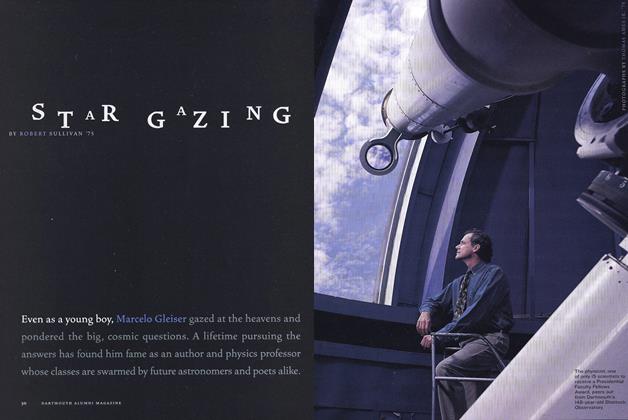

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThree in the Theater

APRIL 1971 By BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

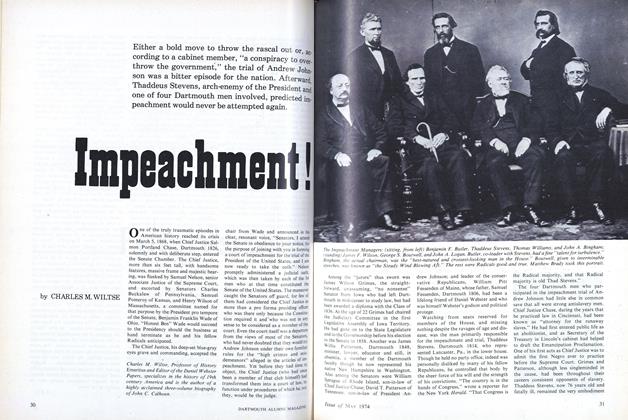

FeatureImpeachment !

May 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MAKE AN AWARD-WINNING DESSERT

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIKA SIMEON '92 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

Jan/Feb 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

FEATURE

FEATUREIdeal Exposure

MAY | JUNE 2019 By STEVE GLEYDURA -

Cover Story

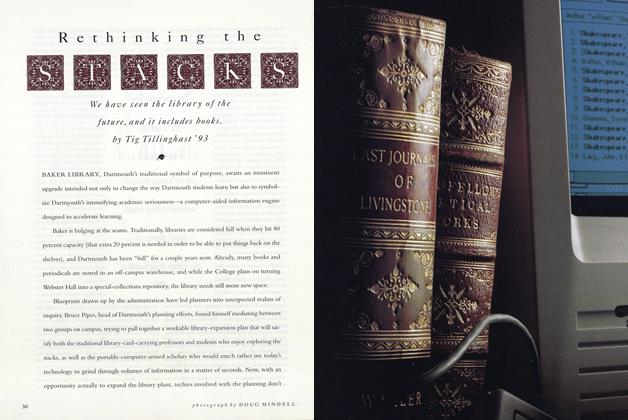

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93