ny new college president, even one who had spent 16 years on the faculty, is bound to be ignorant about some aspects of the institution. In my case it was the Dartmouth Medical School. It is ironic that some of the most important decisions I have had to make were about the future of the Medical School.

The school was founded in 1797. For more than a century it trained a large number of distinguished physicians. But in the 1910s, under the influence of the Flexner Report, there was a wide-ranging reform of medical education in the United States. The Dartmouth Medical School pulled back to a two-year basic science program, and for 60 years our students were forced to transfer to another medical school to receive their clinical training. Questions about the desirability of returning to the status of a fuh medical school were raised 20 years ago. Under the deanships of Drs. Marsh Tenney '44 and Gilbert Mudge, the faculty was significantly strengthened and a nucleus of clinical faculty was recruited.

In 1968 Dean Carleton Chapman persuaded the Board of rustees that two-year medical schools were no longer viable. Although the problems of returning to a full M.D. program have turned out to be much more difficult than foreseen, in retrospect it is clear that Dean Chapman was absolutely correct in his recommendation. Within the last three years the leading medical schools have discontinued their transfer programs and today we could not attract first-rate students to a two-year medical school.

Since World War II, we have witnessed the spectacular growth and improvement of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, of a private group practice in the Hitchcock Clinic, and of the Veterans Administration Hospital in White River Junction. These vast improvements in the clinical facilities enable the Dartmouth Medical School to offer an M.D. program that is small in scale but high in quality.

By February of 1970 the build-up of the Medical School clinical departments was well on its way. Plans had also been developed for a major new physical facility which would double the space available for teaching and research. Through the generosity of several major donors, sufficient funds were in hand so that with federal matching funds we could build the Vail Building and renovate the Remsen Building. The first group of students to be allowed to complete the M.D. degree at Dartmouth were even then being admitted.

At this point in our planning some changes occurred in the federal rules for matching funds, and a serious doubt arose as to whether Dartmouth would be able to complete the building program. I accepted Dean Chapman's recommendation that 16 students be allowed to sign up for the M.D. program con- ditionally, with the understanding that if federal funds were not available, they would be forced to transfer at the end of two years. Since the Board of Trustees had already made a major commitment to a full-fledged medical school, it seemed to me worth taking a risk rather than lose the momentum of the program and the enthusiasm of the faculty. More than $5 million in federal funds was eventually obtained and the program has progressed on schedule.

By 1972 much more serious problems were confronting the school, and the President found he needed a crash course in medical education. Dean Chapman brought to the Board of Trustees a set of problems, some of which had been anticipated in 1968 and some of which were the result of drastic changes in federal funding policies. Medical education is by far the most expensive program in all academia. There is no substitute for students learning the examination and care of patients first hand, in very small groups, under the supervision of a senior physician. It is estimated that the training of medical students costs $15,000 per student per year. Therefore, no medical school can operate without significant federal and state subsidies.

During the decade of the '6os, the federal government adopted a most unfortunate indirect means of subsidizing medical education. There was resistance to the direct subsidization of medical education but great enthusiasm for building up the research capacity of medical schools. Therefore, education had to be "bootlegged" with severe limitations on the time a member of the research faculty could spend teaching. As a result, medical schools commonly have less than two students per faculty member! While the build-up of the research potential of the nation is to be applauded and has contributed to spectacular break- throughs in medical science, all medical schools have become heavily dependent on the federal government. When in the early '70s significant federal cutbacks were made, a financial crisis was created for medical education.

The crisis at Dartmouth was particularly acute. In retrospect it was not realistic to attempt to implement a full M.D. program for a school that had only $5 million in endowment funds. In addition, although our school is the only medical school in the State of New Hampshire, at that time no state funds were available. It appeared that the faculty of the Medical School was being built up to a level that we could not possibly sustain. While Dean Chapman's plans as presented to the Board of Trustees had been realistic, we had underestimated the expectations that build up when a first-rate clinical faculty is recruited. The hopes of various chairmen for their departments were far in excess of the original plan, and there also loomed the danger that we would outgrow the added space provided by the Vail Building. In addition we were facing the problem of combining four separate legal entities - the Medical School, the hospital, the clinic, and the VA Hospital - into a teaching medical center. Dean Chapman became convinced that he had carried the battle as far as any single individual could and that a new dean would find it easier to solve the problems.

The Board of Trustees requested an in-depth survey of the financial needs of the Medical School to determine the minimum requirements for supporting a quality M.D. program. At the same time they requested me to take whatever steps were necessary to move closer to a true medical center.

During the following very hectic year, a number of parallel efforts had to be carried through to a successful conclusion. I turned to Dr. Tenney, who had previously served the Medical School with distinction as dean, to serve once more as its acting dean. It is to his tremendous credit that he managed to see the school through some extremely difficult months during which its very survival was in doubt. I turned to the then associate dean, Dr. James Strickler '50 to direct an intensive survey of the finan- cial needs of the Medical School. The result was a significant lowering of expectations as to the size of the faculty and the institutional funds on which departmental chairmen could count. It says much about the caliber of Dr. Strickler that after he had played this difficult and unpopular role his election as dean of the Medical School was greeted with enthusiasm!

In the meantime complex negotiations were in progress among the four constituent organizations to draw up a charter for a medical center. The Medical School was ably represented by Dr. Tenney and other members of the faculty. The Board of Trustees was represented by Lloyd Brace '25, who made a major contribustitutional tion to the negotiations. But the agreements could never have been reached without the significant and constructive roles played by Dr. Jarrett Folley, president of the Hitchcock Clinic, and S. John Stebbins, president of the Hitchcock Hospital trustees. Thanks to their efforts, today we have a Center Management Committee that can make day-by-day decisions for the Medical Center, and a Joint Council, a trustee-level group charged with long-range planning and the resolution of disputes for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

In the meantime I personally chaired the search committee for the new dean and - as we originally planned - a vice president. We conducted a wide ranging search and interviewed a number of leaders of medical education. While we would eventually recommend unanimously that we choose our inside candidate, Dr Strickler, the procedure served both to assure us of the wisdom of our choice and to gain invaluable advice for the best administrative ministrativearrangement.

It became clear from the discussions that the customary structure of having a vice president for health affairs and a dean was not appropriate for Dartmouth. Instead of a vice presidential position at the College, we created the position of a chief officer for the Medical Center, which would be the executive arm of the Joint Council. The president of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center does not have direct-line authority over the various chief administrative officers, but he serves as planning coordinator and as chief negotiator when disputes arise. We were most fortunate to attract Howard Newman '56, who had just completed four years' distinguished service in the federal government. Finally, we created a board of overseers for the Dartmouth Medical School. Such boards serve to advise both the dean and the Trustees and have played an important role in the history of Tuck and Thayer schools.

When the Board of Trustees was satisfied that a realistic plan for the future of the Medical School had been created, and that the new Medical Center structure significantly improved our chances for success, they made a major commitment to raise the necessary funds to support the school. Although our survey had resulted in a sharp scaling down of the plans of the school, it showed that $1.5 million in new funds, would be needed annually to assure us of a high-quality program. It was the decision of the Trustees that an intensive but selective fund drive be launched to provide these funds so that the existence of the Medical School would not drain the resources of the rest of the institution. The Dartmouth Medical School can both provide the highest quality medical training and have a unique opportunity as part of the Medical Center to contribute to the up-grading of rural health care in the north country. It is the hope of the Board that this very unusual school will attract the support of foundations and of individuals, including individuals not previously connected with Dartmouth College. We are most fortunate that William Morton '32, a member of the Board of Trustees, has agreed to lead this all-important fund drive.

If the financial problems can be solved, the future of the Medical School looks very bright. In 1974 there were 3,000 applicants for 64 places in the entering class. The school has been successful in attracting, and holding, faculty members of national distinction. And the early responses to the fund drive indicate that if economic conditions improve, the goal is achievable. But the next few years present a major challenge to the Dartmouth Medical School.

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Cover Story

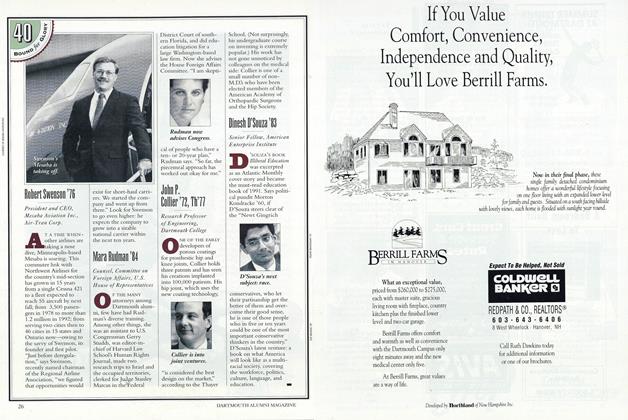

Cover StoryKEGGY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GOALS of a Business Society

June 1958 By ALBERT NICKERSON -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

JUNE 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

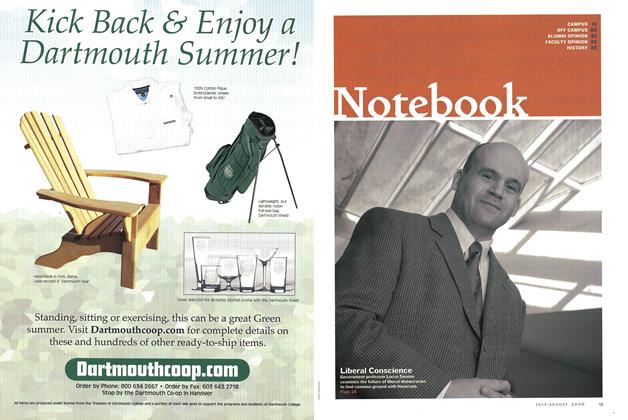

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer