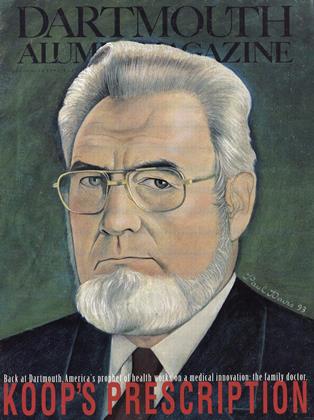

Imagine showing a rash to your family doctor via a video monitor in your living room. Face to electronic face, you describe your symptoms, she asks you diagnostic questions. She might even have you take your own temperature with a thermometer that plugs right into the computer link-up. Within minutes you have your diagnosis; your pharmacist immediately fills a prescription your doctor ordered by electronic mail. And you never had to leave home, except, perhaps, to pick up your medication. Welcome to a new breed of house calls, part of the burgeoning number of ways that doctors and patients are making connections.

C. Everett Koop "37 has always maintained that house calls are good medicine. Trouble was, of course, that they required busy physicians t travel to their patients, a drawback that made house calls all but disappear. House calls are now coming back, minus the travel time, thanks to a new generation of supercomputers and fiberoptics that bring people together at the touch of a button.

Even when you visit your doctor in person, chances are that your care will increasingly make use of the communications networks that are making the nation—perhaps even the world—seem like one giant clinic. Well-wired doctors at Dartmouth are already experimenting with forwarding images, data, and even live consultations with patients to colleagues across the hospital and across the nation. The Dartmouth doctors have plans to link general practitioners in rural New England to the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center electronically.

They are not alone. When physicians in Yellowstone National Park have a question about an X-ray, they use a fax-like device to digitize the image and send it over the phone lines to experts at Cody's West Park Hospital, 80 miles away. Baylor College of Medicine in Houston has even bigger plans. According to The New York Times, the school will use a NASA satellite system to enable Texas physicians to consult with surgical patients from Russia to Saudi Arabia.

Perhaps the most audacious tele medical venture is a portable defibrillator manufactured by a New Jersey company that allows doctors to diagnose and treat heart-attack victims over the phone. The product, called MDphone, works like this: If a lay person encounters a heart attack victim and the MDphone is available, he or she simply attaches victim's chest. The MDphone is programmed to dial the closest hospital with doctors trained to use the technology. The attending doctor receives the patient's electrocardiogram over the phone line. If necessary, the physician can push a button to administer a shock and restart the heart. The product has been used hundreds of times and has saved roughly 25 lives, according to a company executive.

Worried that all this techno-care will further displace human care? Not if your doctor has been influenced by a key idea the Koop Institute is trying to bring to national attention: that physicians should take the time to get to know their patients, educate them about treatment options, and listen to their thoughts. Your doctor may augment discussion of treatment plans by giving you an interactive video like those already being produced by Dartmouth's Jack Wennberg (see the May 1991 issue of this magazine). Interactive videos let you explore treatment options at your own pace, arming you with more knowledge than is possible to absorb in a single office visit. Meanwhile, your doctor can consult the latest in "outcomes research" (also a Wennberg initiative) to see which treatment plans actually yield the best results. Then together you can decide what is right for you.

Docs will be linked to the new medical center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

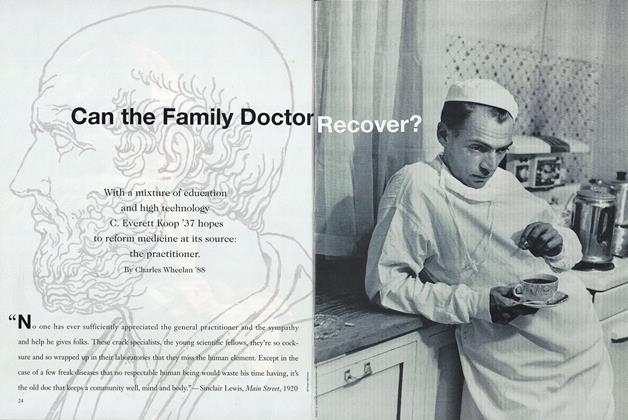

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

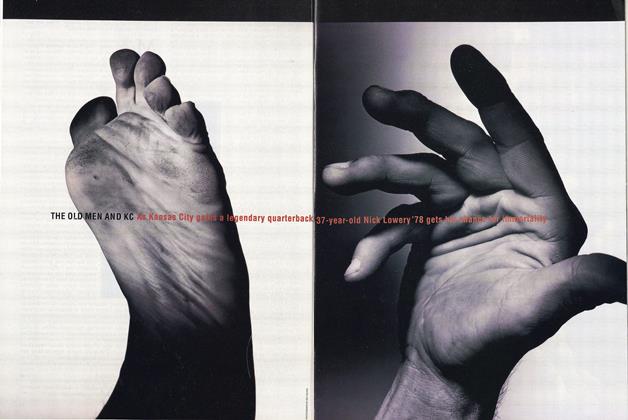

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

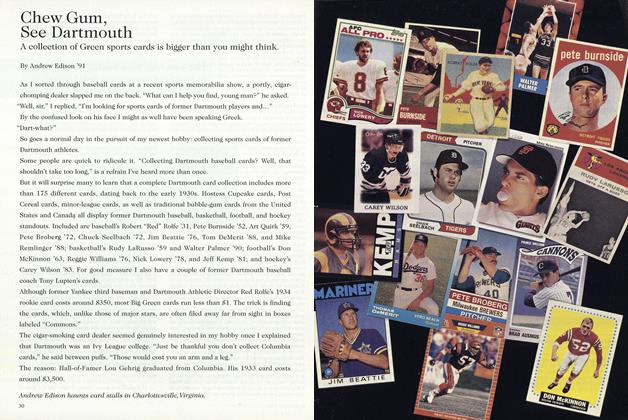

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Sports

SportsTurning Pro

June 1987 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleImprover

MARCH 1988 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

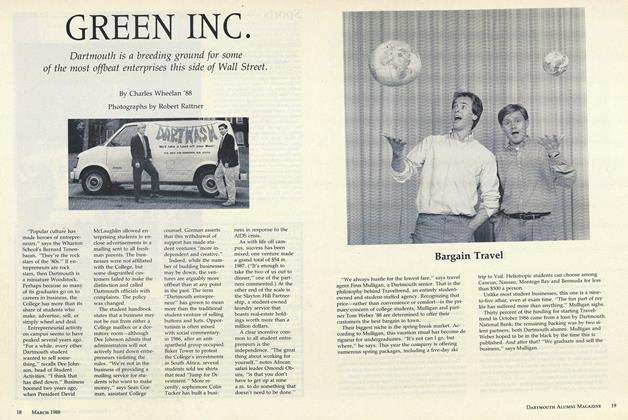

Cover StoryGREEN INC.

MARCH 1988 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

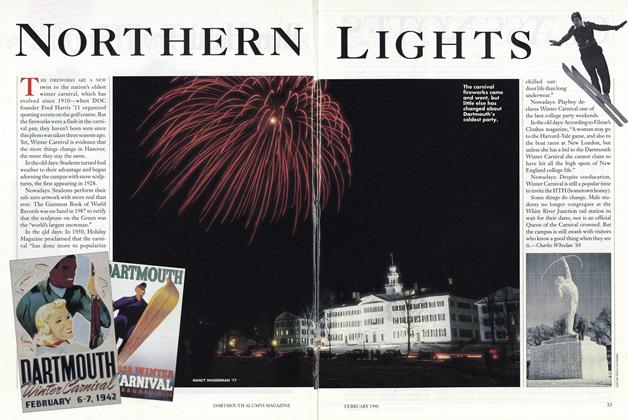

FeatureNorthern Lights

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Interview

Interview“A Privileged Position”

Nov/Dec 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

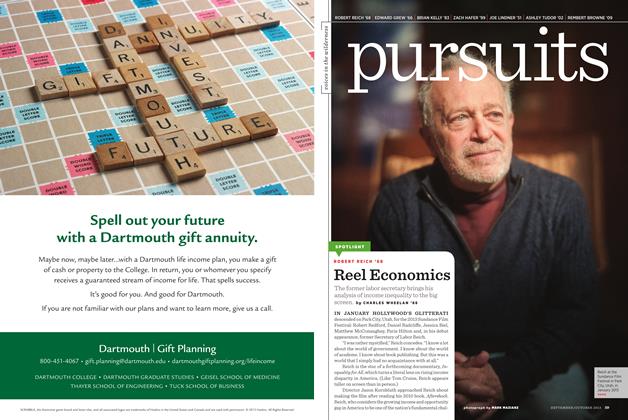

ArticleReel Economics

September | October 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88