What had she missed by not sticking around for June?What was she gaining by coming back?

Not one for the grand gesture, what I remember best about my last days on campus was drinking cupfuls of Tia Maria at noon in a friend's room after I'd just slipped my last paper under a mean professor's door. Make no mistake: This is not a memory I cherish. It ranks right up there with other memories I don't cherish, such as slipping and falling right in front of Thayer on the first snowy day of my freshman year, to the delight of the assembled congregation of suitably attired diners. (I was sporting ballet slippers, for God's sake, in what I can only recall as some wild desire to appear sweetly feminine. Needless to say the delicate effect was severely undermined when I ended up on my backside.)

But there I was, stretched out on my kindly indulgent pal's floor, listening to Meat Loaf's Bat Out of Hell and thinking, Hey, I'm almost outta here. This was in December of my senior year. If there were others in my class also leaving Hanover for good that bleak winter of what was still 1978, I didn't know them.

I chose to graduate early for reasons nearly unclear to me now, involving financial and emotional deprivation, involving a growing sense of uneasiness at life in a small town and the knowledge that I was no more a man of Dartmouth after three years than I had been in 1975. In retrospect the time resembled nothing so much as the ending to an uncomfortable marriage made in one's first youth; an old joke involves one old friend saying to another, "Harry, I hear you're getting a divorce. Why?" To which Harry answers smilingly, "Because I can." Mostly I left because I could and there seemed to be few reasons to stay. For years it was something I didn't think about much. It has become something I now regret.

I thought I was impervious to departure. I thought it would never matter that I hadn't gone to a college graduation. After all, I pretty much erased the high school version, which involved appearing on stage with the thousand other kids from my class for about three minutes. We looked like extras from an old Cecil B. DeMille movie right before the burning of Rome. The one photograph my father took after the high school ceremony unfortunately positioned me directly in front of a sign blaring, "No Parking Anytime." Maybe if the sign were in Latin it would have looked more like a graduation and less like Halloween, but, standing in a white rayon rented gown, I looked like a cross between a very fallen angel on a bad hair day and a Klansman.

So what could I be missing by not sticking around Hanover for two terms, paying what didn't need paying for? Friends, good friends who continue to be the best thing about my years at college, even then sug- gested I stay, that I find a job, or—at the very least—that I return from wherever I was in order to attend graduation in june. Faculty members who had been protective and generous and kind also said that maybe I shouldn't be so in love with final exits, shouldn't get so hooked on the smoke of burning bridges. They were right, but I couldn't see that then.

The decision to graduate early made every difference in those last three months One of the things I could never get used to in Hanover was adults say in perfectly serious voices, "Let's go to. the Hop," because I al ways added, silently, the bass singer's follow-up on the 1950s 45: "Oh baby." But that last winter I remember sitting by a fire in the Hop while somebody played the piano. Struck by a sense of how inviting it was, I realized, for the first time, that I hadn't accepted the invitation. And, shrugging my shoulders, I thought it was too late to do anything about it.

Having tea and cookies at Sanborn House on a November afternoon after spending several dusty hours in the stacks also made me shiver with the idea that maybe I was leaving with my pockets empty. I thought about one of my cousins, who, when hearing that I was at college and working parttime at the writing center to earn my keep, commented that my days involved "no heavy lifting." I remembered his remark as I folded my hands around the warm cup of Constant Comment and watched the steam stealing all the heat. As lives went, mine was pretty privileged. For my three years at Dartmouth I had been struck with a sense of being unwelcome, but how much more welcome I felt now that I was leaving. In December I took the bus back to New York for the last time, vowing like Scarlett O'Hara, with her fist to the sky, that I would never take a long bus ride again.

By the time June came to Gower Street in London, Hanover seemed to be on another planet, not merely another continent. My friends sent letters describing their plans for the big weekend and I admit to feeling a deep, gut-level sense of envy. For many it was a big family event, with their becoming the most recent Dartmouth graduate in a long line of brothers, fathers, uncles and grandfathers. For others from neighborhoods more like mine, it was still a big day, maybe bigger: it was the world's acknowledgment that they had succeeded, that someone in the family had made good. My father wrote on lined paper to ask me if I wanted to come back for the event but I declined his too-generous invitation. I couldn't justify the expense, I explained, but I was giving myself too much credit. Now I realize that I must have been afraid to go back because I already suspected that I had cut my losses too soon, and that I had taken my vulnerabilities with me flying across the ocean clutching the stub of a one-way ticket.

things happened at graduation, I heard. Great laughter, great speeches, great goodbyes and promises of future meeting. I could only half listen to the stories because otherwise I would have been caught up in longing; I had made my bed, I thought, and should lie in it, even when offered the possibility of more congenial lodging. I said I wasn't going back. James Joyce's silence, Great exile, and cunning came to mind and I figured I could manage the last two even if the first seemed impossible. But Dartmouth, venerable institution it is, can hardly match leaving Ireland and the Catholic church; to ally myself with joyce was disingenuous, a cover for my own fears and stubbornness. I was looking for excuses not to go back, and found many. Until a few years ago.

With his camera he took all the pictures I never had from my legitimate time there: of me in front of Baker Library, in front of my old dorm, in front of Thayer pointing to where I had fallen. It was a gradua- tion of sorts, this return, because I saw that I had falsely denied the ef- fect—positive and negative—that Dartmouth had had on my life. I learned that it was after all only polite, as a southern friend once pointed out, "to dance with the one that brung ya." It felt good to dance with my past, but I felt the gentle rebuke of a place that didn't need but surely de- served more credit than I had allowed.

Fortunate enough to have been invited to speak to a number of college and school graduations over the last few years, I always make a point of telling the graduates that, for better or worse, this is a day they will inevitably recall, and suggest that as a service to their older selves they make the best of it, that a later draft of themselves will be eavesdropping on this day for the next 40 or 50 years.

We had a bottle of champagne, not Tia Maria, that night of my first trip back to Hanover, and my husband and I toasted to a sense of return which, as all senses of return do, offered the comforting possibility of closure. We invented the ritual, improvised the steps and ad-libbed the lines, but that first night back was a celebration nonetheless. To the young woman I had been at the bus stop in White River that December, and to the others who had left in June without breaking a visible ribbon, we raised our glasses to say the words that were not provided at the time. Happy Graduation.

I had taken my vulnerabilities with me flying acrossthe ocean clutching the stub of a one-way ticket.

Gina Barrueca teaches English atthe University ofConnecticut inStorrs. Her latestbook is an editedvolume, Fay Weldon's Wicked Fictions

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

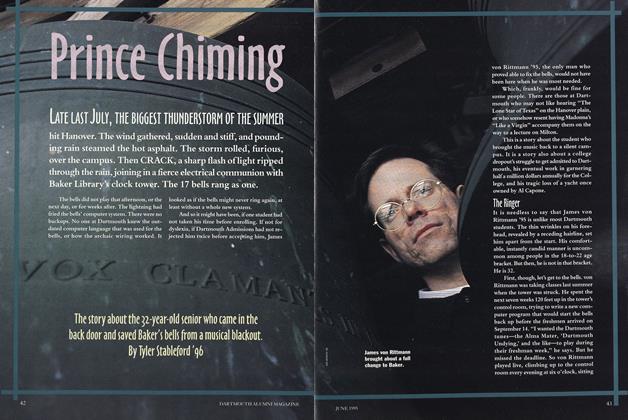

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

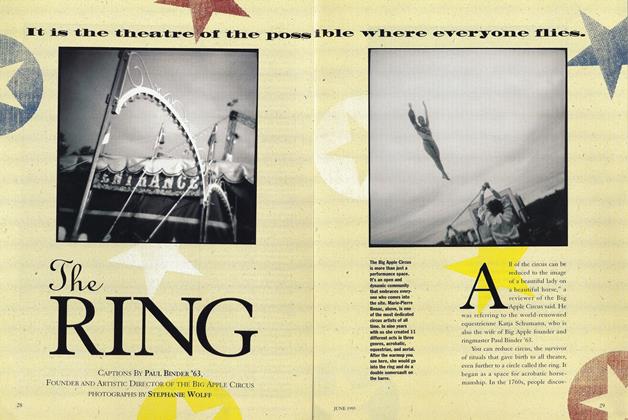

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe RING

June 1995 By Paul Binder '63 -

Article

ArticleMemory and Catastrophe

June 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1995 By George M. Thompson Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

June 1995 By Morton Kondracke

Regina Barreca '79

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorWhither the Greeks?

MAY 1999 -

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureMoney and Luck

MARCH 1999 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

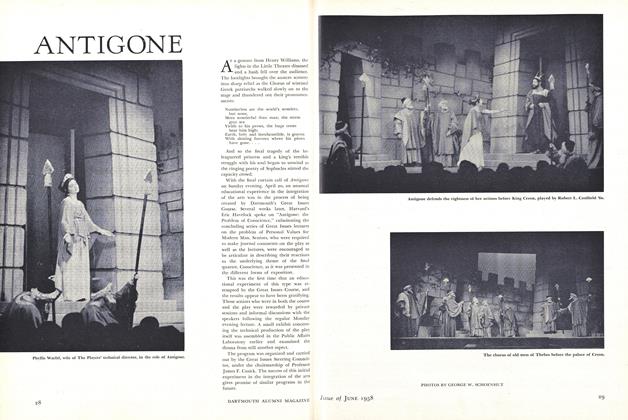

FeatureANTIGONE

June 1958 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureChronicling the DOC

DECEMBER 1984 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

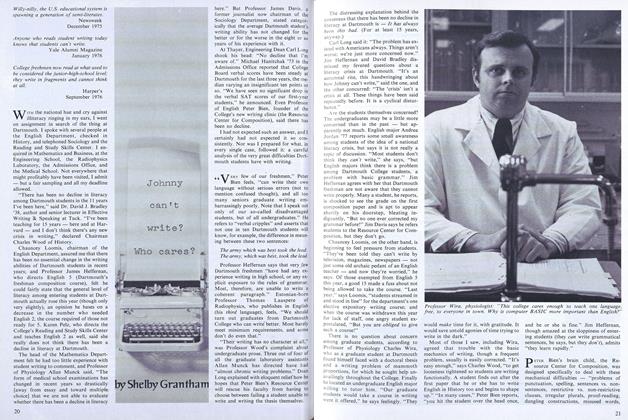

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWhat Makes Nice People Nice?

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By TERESA WILTZ ’83 -

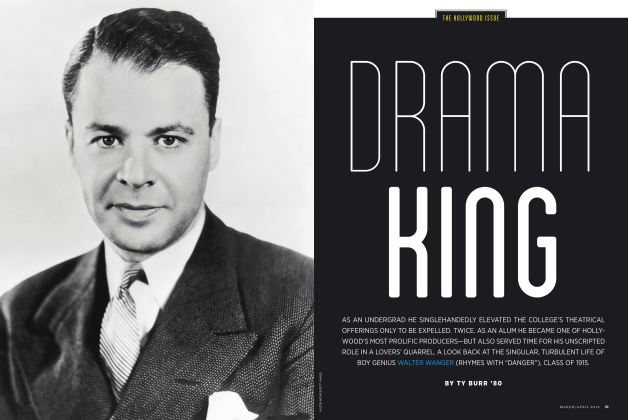

Feature

FeatureDrama King

MARCH | APRIL By TY BURR ’80