Dartmouth curators and professors tell what they see in these paintings.

The Jolly Washerwomanby Lilly Martin Spencer, 1851.

Lilly Martin Spencer was one of the few American women artists who supported a family—a husband and seven children—solely through the sale of paintings. Depite considerable fame, she struggled to make ends meet throughout her career and selected her subject matter according to what she hoped would sell.

The work depicts the artist's own servant—probably Jane Thompson, a Scottish-born woman. Spencer (whose mother was an outspoken feminist and a Fourierian Utopian devoted to communal living and sharing household chores) seems to have been sympathetic toward her servant. The washerwoman, whom Spencer praised, albeit patronizingly, in an 1851 letter as "the best creature in the world," has a warm, cheerful expressiondirected initially at the artist. By 1857 Spencer was creating far less flattering images of servants in her paintings, and in letters complained bitterly of her domestic travails.

Spencer's focus on the domestic labor of women—her meticulous rendition of everything from dirty clothes, soap, and washboard to clothes awaiting rinsing, pans for heating water, and clothespins lying ready for use—demonstrates not only the emerging "cult of domesticity" of the latter half of the nineteenth century, but the growing influence of women as consumers, particularly in the selection of such household appointments as paintings.

Barbara J. MacAdam Curator of American Art, Hood Museum

When Lilly Martin Spencer painted TheJolly Washerwoman in 1851, a significant debate was raging over the character and quality of the national culture. Should American art emulate European grand tradition or constitute a new vision, free from the constraints of academic theory? Nationalist critics, fueled by the imperatives of American exceptionalism, urged painters and sculptors to produce "a fully democratic art," grounded in the experience of common people rather than an aristocratic elite.

Spencer establishes a fresh paradigm for the happy worker in the new-world Eden of America. The artist's hardedged, realistic style rejects the European "painterly" manner, formulating a pictorial aesthetic that is both legible and congruent with the vernacular subject. No eccentric signature brushwork intervenes between the direct gaze of The JollyWasherwoman and her presumed "democratic" viewer.

Robert L. McGrathProfessor of Art History

Many nineteenth-century European artists carefully depicted details that alluded to a person's class. This painting by an American artist reflects this proclivity. Spencer has chosen to describe the tear in the washerwoman's dress, her unidealized physiognomy, and her chafed and reddened skin. However, The Jolly Washerwoman promotes and idealizes a distinctly non-European relationship between female servant and master, promoting instead an almost familial connection between those served and those providing service. There is no ambiguity about the relationship of this servant to the person who has interrupted her work. The washerwoman, patiently posing at her washtub, expresses complete acceptance of the artist/viewer. No Upstairs/Downstairs formality for this American household, no Dutch-style moralizing about idle help, but also no ambiguity about the lower status of the laundress. Also no sign of sexual invitation in her gaze or dress, which was part and parcel of the predominantly male European tradition of depicting this type of female servant.

Katherine Hart Curator of Academic Programming, Hood Museum

When American artists move from painting the urban gentry to posing their servants, we see the country as it coped with tremendous social changes. The Jolly Washerwoman shows us the nineteenth-century America that sought refuge in our homes from industrialism, urbanism, and immigration. Houses became sanctuaries secured from the noise of factories, the din and dirt of the street, and the unfamiliar customs of immigrants. Americans turned inward, celebrated the virtues of family life, and created a cult of domesticity to keep women at home.

Marlene Elizabeth Heck Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History and History

Two Profiles, No.1by Fernand Leger, 1933

For French artist Fernand Leger, the critical issue was how to create a viable pictorial "language" that could convey meaningand be accessible to the viewer—without resorting to the narrative structure of traditional painting. Created in 1933, Two Profiles attempts to give both the representational and abstract pictorial forms equal value. "A picture must never be judged by comparisons between more or less natural elements," he observed. "Reality is infinite and highly varied. What is reality? Where does it begin? Where does it end? How much of it should there be in painting? There is no answer."

There's a wonderfully dynamic sense of balance in this picture as well as a number of ambiguities that force us to think carefully about how to read it. Do we perceive the planes of color that form the composition as essentially flat, or do they create a threedimensional pictorial space? Moreover, how are we to understand the "two profiles" of the title, which seem both menacing and oddly comical? Are they figures, or are they still-life elements, and how do they relate to the strange, plant-like form at the right? As Leger himself noted, in the end it is not particularly useful to look for specific answers to such questions; rather, it is more important to try to approach the work on its own terms. Recalling his famous dictum that "realism in painting should be the simultaneous fusion of three basic pictorial elements of line, form, and color," he argued that "A picture has value in itself, like a musical score, like a poem."

Timothy RubDirector,Hood Museum of Art

Although Leger was more a fellow traveler than active member of the surrealists, his work in this painting resembles the "illusionist," as opposed to the "automatic," style in surrealism. Instead of painting a dream-like image while in a dream-like state, which is how an automatic painting would be executed, the artist recalls a dream-like moment and recreates it after the fact, giving the illusion—as in much of the work of Rene Magritte—of seeing the artist's dream. In actual fact, however, the painting was meticulously produced over some length of time and not at all in a dreamy fashion.

The painting can be read as surrealist in another sense, too. The two profiles' joint contemplation of the sun-like energetic shape facing them suggests the ethic of partnership that was typical of surrealism.

Katharine Conley Assistant Professor of French and Italian

An austere yet elegant painting, Two Profiles,No. 1 shows Leger's interests in portraying objects abstracted from everyday life and in dynamic contrasts. Since his cubist period, Leger believed that the proliferation and intersection of objects in modernity—including machines, vegetation, and the human figure—should form the basis of modern art. In much of his work he rejected traditional artistic subjects, such as those found in mythological and history painting, as outdated and inappropriate to the changed circumstances of twentiethcentury reality and art. TwoProfiles, No. 1 features a canvas divided evenly between highly abstracted human profiles and a vegetal form, all floating on a monochrome background. The equally weighted halves of the painting set up both a contrast and an equivalence between the abstracted objects depicted, suggesting that these forms, no matter what their sources, are of equal importance. The rhythmic counterpoints between the shapes, their color patterns, and their outlines also counterbalance the restricted palette and the almost entirely flat paint treatment throughout the work.

Leger painted Two Profiles,No. 1 at a time of intense artistic debate in France about the object, subject, and realism and about the social and political roles of the artist, concerns stemming from the Depression and the rise of fascism. Although Leger nominally defended the object rather than the subject as the basis for modern painting in the debates, he also recognized the need to make art relevant and accessible to the modern viewer. These concerns helped to transform his objectfocused investigations like Two Profiles, No. 1 into his well-known monumental subject paintings of the mid to late 1930s, such as Adamand Eve.

Diane Miliotes Visiting Instructor of Women's Studies

The Jolly Washerwoman Lilly Martin Spencer

Two Profiles, No. 1 Fernand Léger

"Reality is infinite and highlyvaried. What is reality?Where does it begin? Where does it end?How much of it should there be inpainting? There is no answer."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

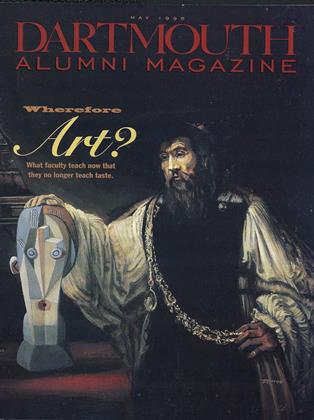

Cover Story

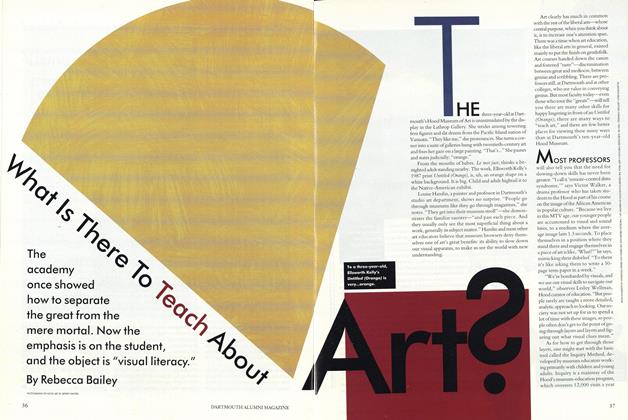

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

May 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

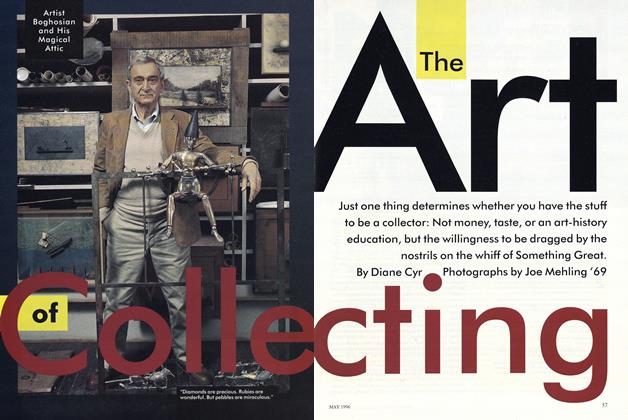

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

May 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

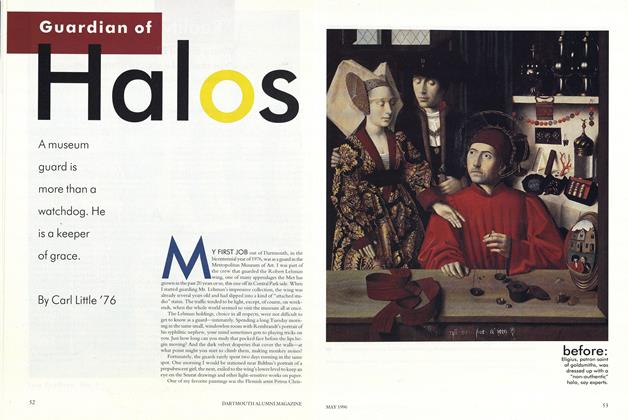

FeatureGuardian of Halos

May 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

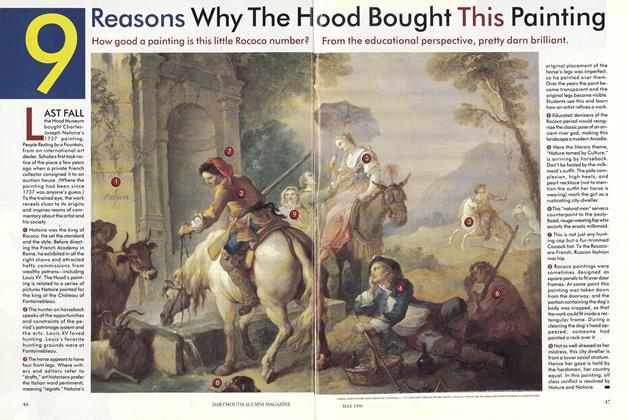

Feature

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

May 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

May 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Feature

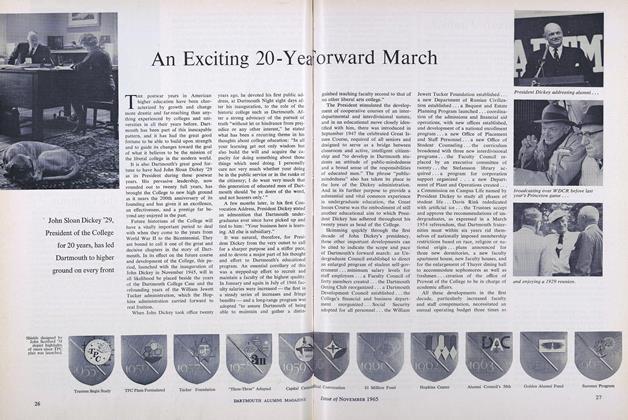

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

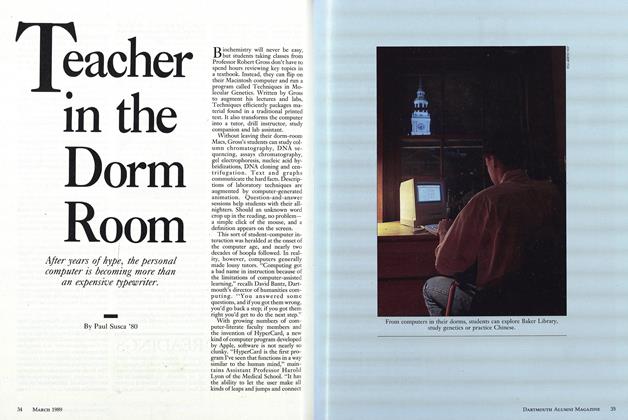

Cover StoryTeacher in the Dorm Room

MARCH 1989 By Paul Susca '80