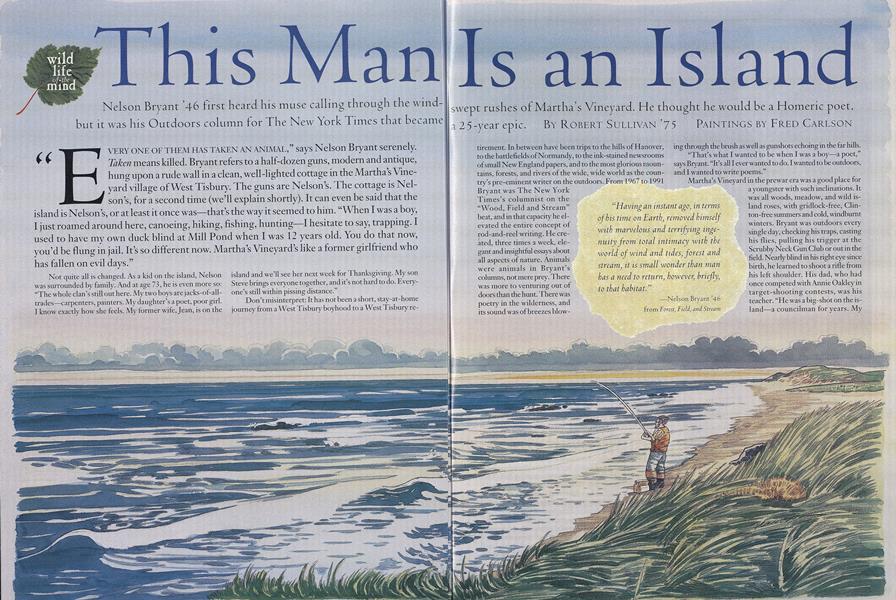

Nelson Bryant "46 first heard his muse calling through the windbut it was his Outdoors column for The New York Times that became swept rushes of Martha's Vineyard. He thought he would be a Homeric poet, a 25-year epic.

EVERY ONE OF THEM HAS TAKEN AN ANIMAL," says Nelson Bryant serenely. I Taken means killed. Bryant refers to a half-dozen guns, modern and antique, hung upon a rude wall in a clean, well-lighted cottage in the Martha's vinevard village of West Tisbury. The guns are Nelson's. The cottage is Nelson's, for a second time (we'll explain shortly). It can even be said that the island is Nelson's, or at least it once was—that's the way it seemed to him. "When I was a boy, I just roamed around here, canoeing, hiking, fishing, hunting I hesitate to say, trapping. I used to have my own duck blind at Mill Pond when I was 12 years old. You do that now, you'd be flung in jail. It's so different now. Martha's Vineyard's like a former girlfriend who has fallen on evil days."

Not quite all is changed. As a kid on the island, Nelson was surrounded by family. And at age 73, he is even more so: "The whole clan's still out here. My two boys are jacks-of-all- trades—carpenters,painters. My daughter's a poet, poor girl. I know exactly howshe feels. My former wife, Jean, is on the island and we'll see her next week for Thanksgiving. My son Steve brings every one together, and it's not hard to do. Everyone's still within pissing distance."

Don't misinterpret: It has not been a short, stay-at-home journey from a West Tisbury boyhood to a West Tisbury re tirement. In between have been trips to die hills of Hanover, to the battlefields of Normandy, to the ink-Mained newsrooms of small New England papers, and to the most glorious mountains, forests, and rivers of the wide, wide vorld as the country's pre-eminent writer on the outdoors. From 1967 to 1991 Bryant was The New York Times's columnist on the "Wood, Field and Stream" beat, and in that capacity he elevated the entire concept of rod-and-reel writing. He created, three times a week, elegant and insightful essays about all aspects of nature. Animals were animals in Bryant's columns, not mere prey. There was more to venturing out of doors than the hunt. There was poetry in the wilderness, and its sound was of breezes blow ing through the brush as well as gunshots echoing in the far hills.

"That's what: I wanted to be when I was a boy—a poet," says Bryant. "It's all I ever wanted to do. I wasted to be outdoors, and I wanted to write poems."

Martha's Vineyard in the prewar era was a good place for a youngster with suchincl inations.It was all woods, meadow, and wild island roses, with gridlock-free. Clin ton-free summers and cold,windburnt winters. Bryant was outdoors every single day, checking his traps, casting his flies, pulling his trigger at the Scrubby Neck Cun Club or out in the field. Nearly blind in his right eye since birth, he learned to shoot a riflefrom his left shoulder. His dad, who had once competed with Annie Oakley in target-shooting contests, was his teacher. "He was a big-shot on the island—a councilman for years. My mother and father came out here in 1932 when I was eight or nine, so I'm not considered a Vineyarder. But the place was right for me from the first. It was a pastoral place, comforting and sustaining."

You might suppose an adolescent of such a philosophy found his way to woodsy Hanover quite on purpose, but you would suppose incorrectly. All Bryant knew for sure was that he wanted to go to college, and to do that he had to get to the mainland. "A summer family out here thought it would be nice if I went to prep school in Connecticut, so I went to Norfolk and I'd work there gathering wood for the school and so forth to help pay my way. The school had a big draft horse called Nellie, and one day I was plowing and a retired army colonel who lived down the hill came over and said, 'Young man, I like the way you work. We've got to get you to Dartmouth!' I said, 'I haven't got a pot to piss in.' He said, 'We'll get you in, and worry about that later.'"

Bryant was a member of the war-tossed class of 1946. He was to matriculate in the fall of '42, but found hi mself enlisting instead. He longed to be a paratrooper, and through what he calls "a bit of chicanery—covering the bad eye twice, first with my right hand, then with my left," he managed to pass the airborne physical. In basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, a rifle-range sergeant insisted he stop shooting from the left, and Bryant fessed up about his earlier deception. "If you want it that much," said the sergeant, "I'll say nothing."

The sarge's silence proved to be a blessing and something of a curse. Pfc. Bryant made it into Company D, 508 th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the famous 82 nd Airborne Division, and was one of 13,000 Americans dropped behind Utah Beach at two a.m. on June 6, 1944. The paratroopers' assignment was to gain control of roads leading to Ste. MereEglise, thereby preventing German reinforcements from reaching Utah Beach, where thousands of other U.S. troops were landing with the dawn. At first light, Bryant took his first human life: He shot a German soldier walking along a dirt road. Bryant remembers "slowly taking up the slack in the trigger and thinking all the while that the act was indecent, that it would be justified only if he was firing at me." Three days later, the Axis nearly returned the favor. On patrol, Bryant met machine-gun fire: "The single bullet that hurled me on my back was one of a burst that riddled my fellow scout who whispered, 'Help me, help me,' then died." Bryant stumbled back to headquarters on Hill 30 with a hole in his chest, and three days later was evacuated to a tent hospital on the shore of the English Channel. He recuperated in Wales, resumed jumping, left the service at war's end, and returned to New Hampshire, where he began writing an epic poem about his experiences in Europe—experiences he long found impossible to put behind him. For years he would steer post-dinner conversation around to the war, "and then, if sufficiently unhinged by emotion and drink, I would tear off my shirt and invite guests to poke their fingers in the fore and aft indentations. There were times when I set fire to the hair on my chest to add a bit of drama to my antics." But time healed even most of the inner wounds. Bryant wrote on the 50th anniversary of D-Day in 1994: "A decade ago, I wrote that taking part in those campaigns with the 82nd Air borne Division overshadowed all that followed, including love, marriage, career and children. That is no longer true. I have belatedly come to understand that slogging across the plain of everyday life with dignity and as much honesty as one can muster calls for as much heroism, if only because the struggle never ends, as assaulting a flaming hill."

As to "love, marriage, career and children," they came in quick succession for Bryant in the late 19405. He married a Vineyard girl, Jean Morgan, in a candlelight ceremony at Edgartown's Congregational Church on June 22,1946. (The Vineyard Gazette announced the impending nuptials by declaring, "All relatives and friends of the young couple are invited to attend." Such is island life.) Nelson and Jean had a son, Steve, and by age 23 Nelson was a veteran, a married father, and still an undergraduate. "It was hard for veterans," he says. "We'd see the younger students walking across the Green, but our lives were much different than theirs. I was struggling along on the G.I. Bill, working parttime, writing my poem. One nice thing for returning G.l.s was, no required courses. I'm terrified of math and chemistry, so I avoided them.

"Alex Laing ['25] and his wife opened their home to aspiring poets, and oh, God! it was so exciting to go over there and read. I loved Shakespeare, Donne, Blake, Dickinson. I should mention Frost, but when I was at school I was arrogant and liked showier stuff.

"So that was my life—mypoem, a young family, andworking in the wood shop in the evenings as a source of income." As Bryant reminisces, he sits at a beautiful, Shaker-influenced cherry table that he fashioned himself just the year before last.

Bryant received his degree in 1950 and, since the demand for epic poets was light throughout the land, he took a newspaper job with the Claremont Eagle, down the road a piece from Hanover. There he wrote a little bit of everything, and eventually served as Lebanon, New Hampshire, bureau chief. In 1954 he moved to the Gloucester, Massachusetts, Times as sports editor, and two years later back to the Eagle as managing editor. By then he andjean had three kids, and the couple's shared memory of being raised on an island became a constant siren's song. Bryant threw off the security of a steady job and returned with his family to West Tisbury, to the center-island plot of land where he had been a boy, and where he then built a cottage, the one he now sits in as he reviews his life. "The next few years I'd write freelance for Field & Stream and others. Jean's brother had just started a dock-building business, so I built docks around the island. A lot of them are still standing. That was the hardest physical work I've ever done in my life. That'll make you smart, especially in winter."

Bryant might have continued as a freelance writer and itinerant dockbuilder for many seasons more, had fate not intervened. The outdoors writer for the Times—New York's, not Gloucester's—retired in 1966, and a former colleague of Bryant's at the Eagle suggested he audition for the job. He did, and beat out some 30 other candidates. "It was a lot of writingquite frantic, really, all those years. But delightful. I remember often getting quite ecstatic when a piece was done and I looked at it and said, 'Pretty good.'"

Meantime, by the home fires, life came and went. The marriage to Jean did not last, and Bryant moved out. Then Jean moved cross-island to Edgartown, and the companion in Bryant's life, Ruth Kirchmeier, came to the West Tisbury cabin. She sits here now, at the Shaker table Nelson built for her, and says without qualm, "The marriages may be in shambles, but we're happy." Ruth is a painter, an outdoorswoman, and a sometime deerpacker. We'll get to that.

Over the years, Bryant became the very best at things he was already good at: Hunting, fishing, cooking (today we lunch on bluefish stew a la Nelson, and one bowl is simply not enough). Most significantly: writing. In reviewing the product of Bryant's quarter century with the Times, it becomes clear that the man's take on nature runs much, much deeper than the usual stream. (Some items, entered as evidence, appear on the margins of these pages.)

In all chose years with the Times, writing was the sauce, venturing forth was the goose itself. "Covering the outdoors is not like covering a ball game," he says. "You've playing the game." At play, Bryant went after wahoo off Cape Hatteras and tarpon off the coast of Costa Rica. He fished Maine's Kennebec for small mouth bass and the Catskills' Neversink for trout. He hunted grouse on the Scottish moors using falcons, quail in Georgia using his wits. He took wild turkey out of West Virginia and wild duck over Long Island Sound. He hooked mountain mullet in Jamaica and oumananich landlocked salmon in a remote wilderness lake in Quebec. He wrote often about his island, his Vineyard.

Glenn Wolff, the noted illustrator whose intricate drawings regularly accompanied Bryant's essays in the Times, visited the writer in West Tisbury two years ago. "We went fishing at that beach he writes about a lot," says Wolff from his studio in Traverse City, Michigan. "My first impression of him was that I was going fishing with Santa Claus. He is densebig, but stocky—with that white beard and that pipe of his. And he had this big, deep voice, and also a very Santa-like kindness. Politely, he walked up to us and just started ripping up our rigs and putting on flies that'd work. I remember thinking that he was a perfect combination of frankness and warmth.

"So then we're in the surf, separated from one another by quite a ways. I hooked two or three stripers, all undersized.

"Now, all of Nelson's guests had official surf flies. But he just had this little piece of wood with a string attached to it. And he was just pulling them out left and right.

"Later, as we left the beach, he apologized for it being a slow night."

The Boston Globe's outdoors writer M.R. Montgomery enjoyed a not-dissim- ilar evening with Bryant on the Vineyard, hoping for bluefish. He reported: "One minute he was casting, right next to you; the next he was gone, chasing a hooked blue down the beach, unmistakably Mr. Bryant of the Times of New York."

Says Mr. Bryant of the Times, between sips of bluefish stew at his cherry table: "I know how to fish, but I must say I'm not a very good hunter. I'll find myself losing concentration, talking to a squirrel in the forest as the deer runs by." Still, Bryant has taken his share of deerperhaps 30—over the years, and a sackful of waterfowl to boot.

But Bryant is not a man to be defined by his rod or gun, or even by his rod-and-gun writing. He may look the part, but he is not Grizzly Adams. Today we see him at home, sucking contentedly on his pipe .(which won't stay lit), showing off the dozens of reels and lures downstairs, then the freezer where a freshly killed deer rests in pieces. So, sure: he's a big-time outdoorsman. But he is also a gentle man. After touring the cellar, he takes his guests out to his ambitious vegetable garden, then to Ruth's studio where he proudly points out her paintings. Bryant once wrote that most of us need not only wilderness but"the sweet harvest of civilization, its art, music and literature, which was refined only after the day-to-day struggle for survival was ended." Bryant himself is one of these people, as he admitted in the essay. He recalled a visit to Dartmouth's Second College Grant in far northeastern New Hampshire: "I was filled with an ineffable contentment as I cast for trout into a wind that had swept through a cleft in the hills. It seemed as if I had always been there, fishing for something more elusive than trout. And that evening, at a log cabin on the Dead Diamond River, I turned my battery-powered tape player all the way up and sat under the dark spruces to listen to Pavarotti and Beethoven, marveling that a species so recently with stone ax in hand could have created such glorious sounds."

The 26,000-acre Grant has long been a favorite of Bryant's—a half-century ago it was "as much a part of my Dartmouth undergraduate days as the stacks and chimes of Baker," and on the very day after this session at the Shaker table he and his sons will take the ferry off-island to make the five-and-a-halfhour drive to Wentworth Location for yet another late-autumn getaway. They will stay at the same place, the Merrill Brook Cabin, which is like a second home to Biyant, as he once wrote: "I have become familiar with the terrain all around it, including Halfcnoon Mountain, which is to the northeast, and Round and Black mountains on the other side of the Dead Diamond to the west. New country is exciting, but there's a special satisfaction in having a drink of water at the same spring one discovered four decades ago."

That combination of the contemplative and the sporting wins Bryant the admiration of his colleagues—such as Robert H. Boyle, an award-winning nature writer (Acid Rain, Malignant Neglect) and president of the Hudson River Fisherman's Association. "Writers likeNeLson, they're not hybrids blending ele ments of environmentalism with some perverse love for the hunt," says Boyle. "They're the original folks, they're the mainstream. Nelson is a fine writer, an essayist rather than one of those Me-and- Fred-got-this-big-bass' thing. He's in the tradition of Henry Van Dyck and even back to Henry David Thoreau. And as far as the others who...Well, let's just say that some of my worst enemies are people who consider themselves environmentalists, with this business about 'Don't you think it's cruel to shoot a turkey? Don't you think that fish is feeling pain?'"

It is certain that Bryant never asked himself the question in quite that way. But when he points out that each of those guns on the wall has taken an animal, he isn't bragging, he's giving the news. He looks at the guns and he seems to be wondering about them. "Hunting, when I started—it was just as natural as hauling corn," he says, sucking on that unlit pipe. "I've found that as you get older, you get a greater sense for how fragile life is. Thinking about this, sometimes, out in the field, I would absolutely agonize over it. I came to a philosophy that perhaps sounds absurd. I don't hunt anything I wouldn't eat, but obviously I don't need to get my food from the hunt. For instance, yesterday I was in the Adirondacks, and I came back with a big buck. Last night, Ruth helped me skin and package it, and that's the one downstairs in the freezer. We'll bring it to the table at Thanksgiving. It makes sense to me."

He rekindles his pipe, and continues: "We were going hunting up in the Grant once. My brother and I and a few others, including Pete Blodgett, had taken this trip for several years. We're about to set out from the cabin, and all of a sudden Pete said, To hell with it. I'm too goddamn old. All I can do is walk the roads. I'm not going.'

"I can remember distinctly, watching in the gathering twilight, watching the headlights of Pete's car come on, and watching it go down the road. That was it for him.

"So I guess encroaching age will finally do it anyway."

Encroaching age will curtail the cycles of a hunter's year, and finally those of a stand-in-one-place fisherman, too. A writer and thinker, by contrast, keeps writing and thinking until he dies. And even then, his writing and thoughts remain.

Nelson Bryant always takes a Christmas constitutional after his meal, and as he walks the marshes and beaches of Martha's Vineyard, he thinks. Then he comes home to the cabin in West Tisbury, and he writes. "Among all living things, man alone hungers for peace on earth," he wrote one year. "The other occupants of this planet are not so encumbered or so sanctified, nor need they be for the world's well-being.

"Man's peace refers to his dealings with others of his kind, but it would be well to broaden its meaning to include a never failing sensitivity towards all life—a true peace on earth.

"Perhaps man's urge to conquer and consume all his seemingly insatiable hunger for more goods and services, his worship of economic growth which few in power have dared question destines him for self-extinction, or, at the very least, an apocalypse from the rubble of which he will begin again, maimed and chastened. I do not choose to believe this, however, nor to dwell on it with strains of Silent Night about me.

"I choose to think that—like the blue claw crabs of Tisbury Great Pond, or the robins that won't fly south—certain of us are already adapting to meet the ultimate test."

"Having an instant ago, in termsof bis tune on Earth, removed himselfwith marvelous and terrifying ingenuity from total intimacy with theworld of wind and tides, forest andstream, it is small wonder than manhas a need to return, however, briefly,to that habitat." Nelson Bryant '46 from Forest, Field, and Stream

"Even a cursory acquaintance with the starsand planets will add pleasure to the after-hoursof wilderness expeditions. There is a certain comfort in knowing that, in the world of turmoiland chance, the ritual of the heavens is as constant as the force that drives an A tlantic salmonto its natal stream or a Monarch butterfly toMexico each fall."

"When I first saw: the Tetons, it was as ifI had entered a huge cathedral....Often I wouldjust tether my horse in a grove ofalders and sitand contemplate the Snake for an hour beforerigging up my rod. When I did begin casting,I couldn't help feeling that angling for thefunof it in such surroundings was something liketrying to whistle a popular tune while a magnificent anthem pours from an organ."

"Turning inland to Tisbury Great Pond, where large raftsof bluebills and smaller flocks of widgeon rest and where eels liein winter sleep, buried in the mud, thousands of miles from theirbirthplace in the Sargasso Sea, I will, if I am fortunate, find oysters: washed to shore by the prevailing southwest wind. I willshuck a few with my pocket knife and devour them with no condiment save the bracing air."Standing there in the wind, knife in hand, my tiny middenat my feet and the broken stubble of Spartina grass behind me, Imay for I have done so before in that place—gain a sense, albeit fragmented and elusive, of the incredibly complex scheme ofwhich I am both a spectator and a participant."

ROBERT SULLIVAN is a senior editor at Lifemagazine and a contributing editor to thisone. His book, Flight of the Reindeer, is being published this month by Macmillan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

October 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Feature

FeatureDON'T CALL HIM ANONYMOUS

October 1996 By Jeanhee Kim '9O -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

October 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

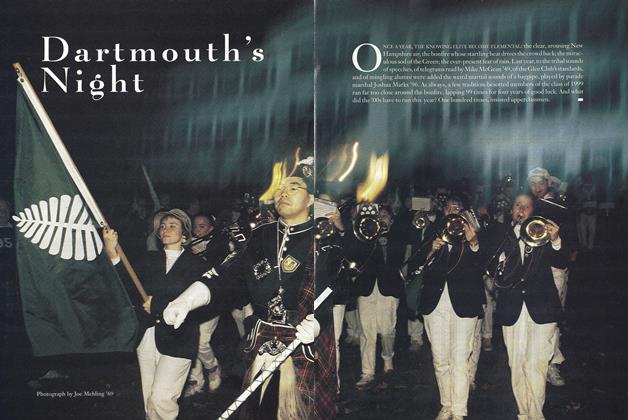

FeatureDartmouth's Night

October 1996 -

Article

ArticleKnowing Your Place

October 1996 By Jim Collins'84 -

Article

ArticleThe Orange on Campus Is Not on Leaves

October 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

Sports

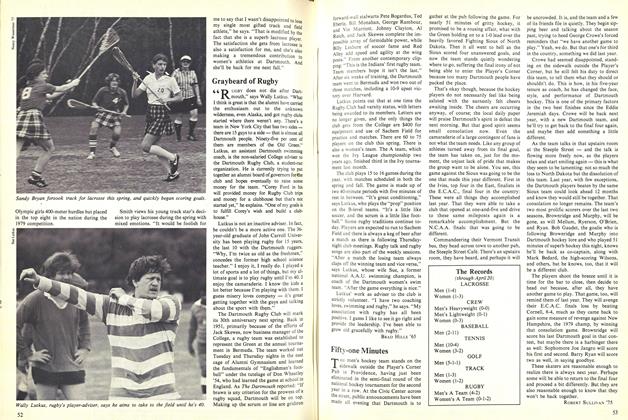

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

MARCH 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

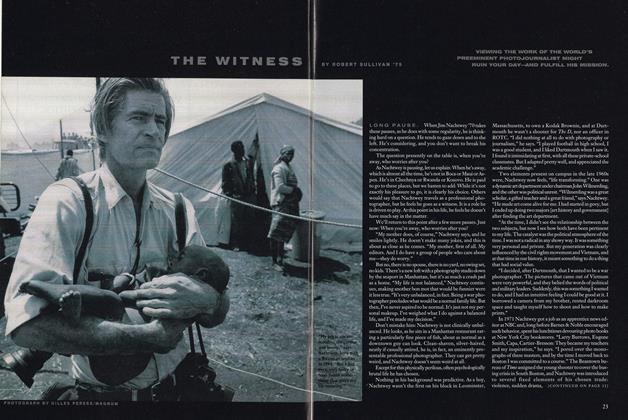

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

Jan/Feb 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMedicine's Moral Issues

October 1960 -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

MARCH 1990 -

Feature

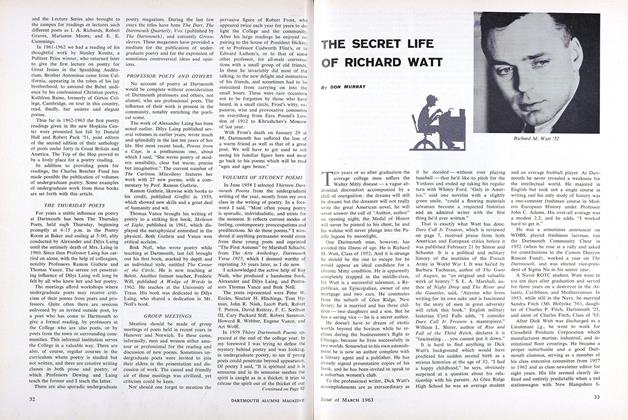

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

MARCH 1963 By DON MURRAY -

FEATURE

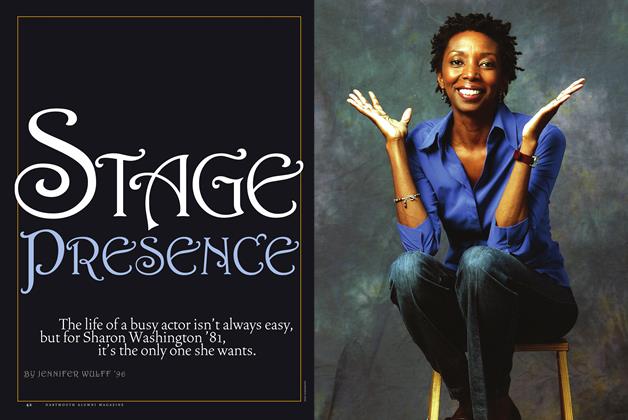

FEATUREStage Presence

Mar/Apr 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

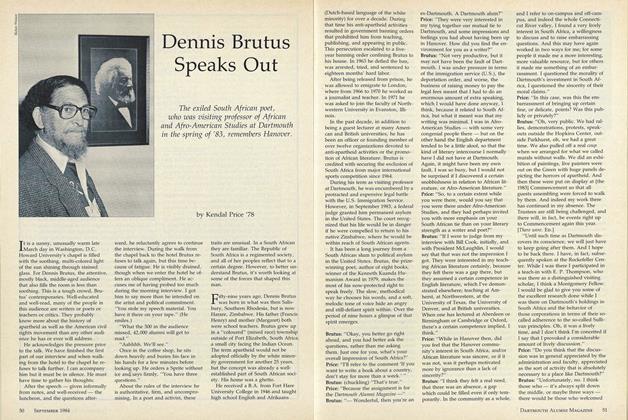

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham