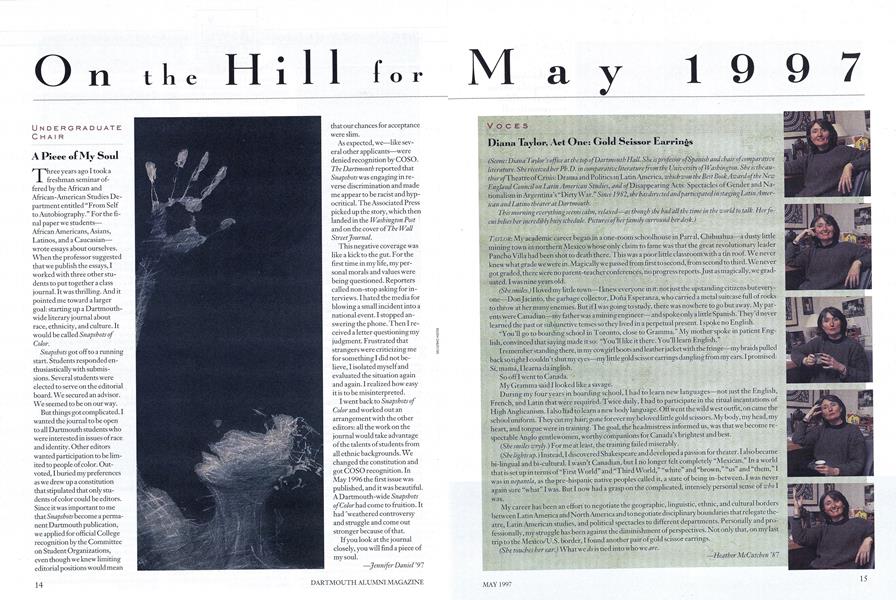

(Scene: Diana Taylor's office at the top of Dartmouth Hall. She is professor of Spanish and chair of comparativeliterature, Shereceivedher Ph.D. in comparative literaturefrom the University of Washington. She istheauthor of Theatre of Crisis: Drama and Politics in Latin America, which won the Best Book Award of the NewEngland Council on Latin American Studies, and of Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina's "Dirty War.'' Since 1982, she has directed and participated in staging Latin Americanand Latino theater at Dartmouth.

This morning everything seems calm, relaxed-as though she bad all the time in the world to talk. Her of cus belies her incredibly busy schedule. Pictures of her family surround her desk.)

Taylor: My academic career began in a one-room schoolhouse in Parral, Chihuahua a dusty little mining town in northern Mexico whose only claim to fame was that the greac revolutionary leader Pancho Villa had been shot to death there. This was a poor little classroom with a tin roof. We never knew what grade we were in. Magically we passed from first to second, from second to third. We never got graded, there were no parent-teacher conferences, no progress reports. Just as magically, we graduated. I was nine years old.

(Shesmiles.) I loved my little town—I knew everyone in it: not just the upstanding citizens burevery-one—Don Jacinto, the garbage collector, Dona Esperanza, who carried a metal suitcase hill of rocks to throw at her many enemies. But if I was going to study, there was nowhere to go but away. My parents were Canadian—my father was a mining engineer and spoke only a little Spanish. They'd never learned the past or subjunctive tenses so they lived in a perpetual present. I spoke no English.

"You'll go to boarding school in.Toronto, close to Gramma." My mother spoke in patient English, convinced that saying made it so: "You'll like it there. You'll learn English

'I remember standing there, in my cowgirl boots and leather jacket with the fringe—my braids palled backso tight I couldn't shut my eyes—my little gold scissor earrings dangling from my ears. I promised: Sí, mamá, Ilearna daingljsh. Sooff I went to Canada. My Gramma said I looked like a savage.

During my four years in boarding school, I had to learn new languages not just the English, French, and fat tin that were required.- Twice daily, I had to participate in the ritual incantations of High Anglicanism. I also had to learn a new body language. Off went the the wild west outfit, on came the school uniform. They cut my hair; gone forever my beloved little gold scissors. My body, my head, my heart, and tongue were in training. The goal tire headmistress informed us, was that we become respectable Anglo gentlewomen, worthy companions for Canada s brightest and best. (She smiles wryly.) For me at least, the training failed miserably.

(She lights up:) Instead, I discovered Shakespeare and developed a passion for theater. I also became bi-lingual and bi-cultural. I wasn't Canadian, but Ino longer felt completely "Mexican." In a world that is set up in terms of "First W odd" and "Third World," "white" and "brown," "us" and "them," I was in nepamla, as the pre-hispanic native peoples called it, a state of being in-between. I was never again sure "what" I was. But I now had a grasp on the complicated, intensely personal sense of who I was

My career has been an effort to negotiate the geographic, linguistic, ethnic, and cultural borders between Latin America and North America and to negotiate disciplinary boundaries that relegate theatre, Latin American studies, and political spectacles to different departments. Personally and pro, fessionally, my struggle has been against the dimnishment of perspectives. Not only that, on my last trip to the Mexico/U.S. border, I found another pair of gold scissor earrings. (She touches her ear.) What we do is tied into who we are.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

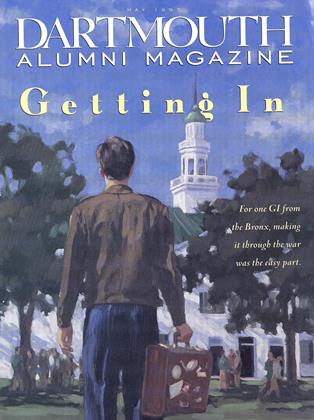

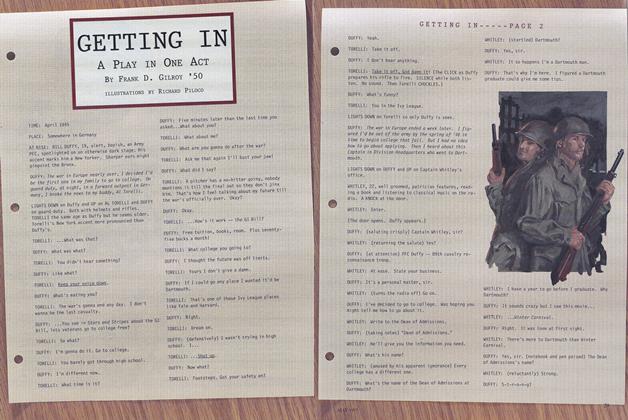

Cover StoryGETTING IN

May 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

May 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

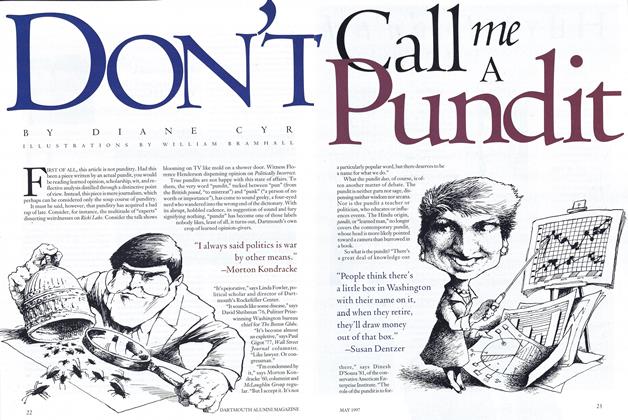

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

May 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Article

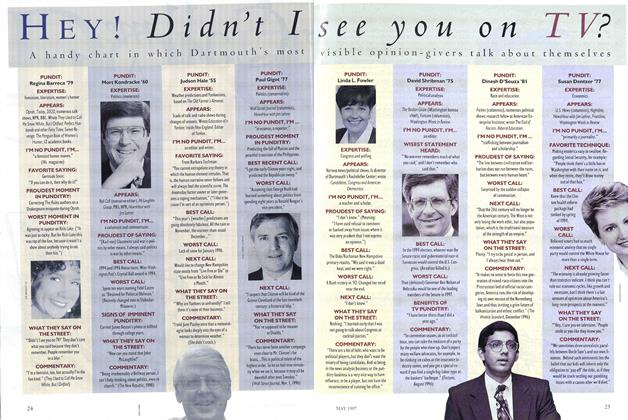

ArticleHey! Didn't I See You on TV?

May 1997 -

Article

ArticleCold Calculations

May 1997 By Christopher Kenneally 81 -

Article

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

May 1997 By "E. Wheelock"