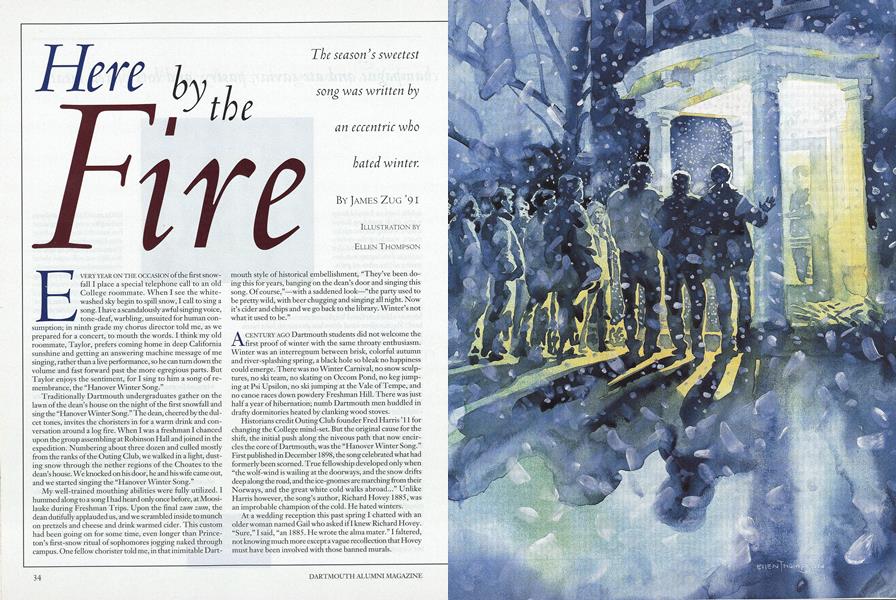

The season's sweetestsong was written byan eccentric whohated winter.

EVERY YEAR ON THE OCCASION of the first snowfall I place a special telephone call to an old College roommate. When I see the white- washed sky begin to spill snow, I call to sing a song. I have a scandalously awful singing voice, tone-deaf, warbling, unsuited for human consumption in ninth grade my chorus director told me, as we prepared for a concert, to mouth the words. I think my old roommate, Taylor, prefers coming home in deep California sunshine and getting an answering machine message of me singing, rather than a live performance, so he can turn down the volume and fast forward past the more egregious parts. But Taylor enjoys the sentiment, for I sing to him a song of remembrance, the "Hanover Winter Song."

Traditionally Dartmouth undergraduates gather on the lawn of the dean's house on the night of the first snowfall and sing the "Hanover Winter Song." The dean, cheered by the dulcet tones, invites the choristers in for a warm drink and conversation around a log fire. When I was a freshman I chanced upon the group assembling at Robinson Hall and joined in the expedition. Numbering about three dozen and culled mostly from the ranks of the Outing Club, we walked in a light, dusting snow through the nether regions of the Choates to the dean's house. We knocked on his door, he and his wife came out, and we started singing the "Hanover Winter Song."

My well-trained mouthing abilities were fully utilized. I hummed along to a song I had heard only once before, at Moosilauke during Freshman Trips. Upon the final zum zum, the dean dutifully applauded us, and we scrambled inside to munch on pretzels and cheese and drink warmed cider. This custom had been going on for some time, even longer than Princeton's first-snow ritual of sophomores jogging naked through campus. One fellow chorister told me, in that inimitable Dartmouth style of historical embellishment, "They've been doing this for years, banging on the dean's door and singing this song. Of course,"—with a saddened look—"the party used to be pretty wild, with beer chugging and singing all night. Now it's cider and chips and we go back to the library. Winter's not what it used to be."

A CENTURY AGO Dartmouth students did not welcome the first proof of winter with the same throaty enthusiasm. Winter was an interregnum between brisk, colorful autumn and river-splashing spring, a black hole so bleak no happiness could emerge. There was no Winter Carnival, no snow sculptures, no ski team, no skating on Occom Pond, no keg jumping at Psi Upsilon, Upsilon, no ski jumping at the Vale of Tempe, and no canoe races down powdery Freshman Hill. There was just half a year of hibernation; numb Dartmouth men huddled in drafty dormitories heated by clanking wood stoves.

Historians credit Outing Club founder Fred Harris' ll for changing the College mind-set. But the original cause for the shift, the initial push along the niveous path that now encircles the core of Dartmouth, was the "Hanover Winter Song." First published in December 1898, the song celebrated what had formerly been scorned. True fellowship developed only when "the wolf-wind is wailing at the doorways, and the snow drifts deep along the road, and the ice-gnomes are marching from their Norways, and the great white cold walks abroad..." Unlike Harris however, the song's author, Richard Hovey 1885, was an improbable champion of the cold. He hated winters.

At a wedding reception this past spring I chatted with an older woman named Gail who asked if I knew Richard Hovey. "Sure," I said, "an 1885. He wrote the alma mater." I faltered, not knowing much more except a vague recollection that Hovey must have been involved with those banned murals.

"My grandmother and he were first cousins and close friends," the woman said. "I have a couple of boxes of Hovey's letters and poems. No one has gone through them before. They're piled in these boxes. You should come look."

A few months later I sat with Gail at a kitchen table in Charlottesville, Virginia, and poked through overflowing boxes. In ancient brown manila folders lay reams of letters and newspaper articles. Paper-clipped notes bore an imprint of rust, and more than a few envelopes carried a single, well-franked onecent stamp. Some of the materials concerned a proposed memorial stone that some Dartmouth classmates wanted to lay at Hovey's grave, a controversy that evidently sputtered and spat for almost 60 years. Magazine essays argued over the hearsay that Hovey, a pro-Spanish-American War man, first coined the phrase "Remember the Maine." I read letters from Bliss Carman, an intimate friend of Hovey's and co-author of two popular books of poems, Songs of Vagabondin. I pulled out crinkly obituaries from a dozen newspapers after Hovey's death, from a heart attack, at the age of 35 in 1900. Carman wrote one in Harper's Weekly and spoke of his "sheer grasp and capacity of intelligence, that lucid wide spirit."

Tom, Gail's imposing, straight-backed husband, kept coming in and out of the kitchen where we worked. Occasionally he picked up a letter or article and posed a question. "How do you think he made money?" Tom asked when reading an article about poets in the nineteenth century. He excavated a couple of Bliss Carman letters and asked, "Do you think they were lovers?" With the explosion of films and plays about Oscar Wilde, a contemporary of Hovey's, I could not be sure. Hovey, like Wilde, married and had children and was likewise famous as a flamboyant aesthete, a lover of art, a deliberate provocateur. In backwoods Hanover, Hovey stood out. He wore his hair long, cultivated a long mustache, carried sunflowers, and maintained an unconventional wardrobe of oversized felt hats, pastel-colored stockings, and polished riding boots. He marched, Tom thought, and I had to agree, to his own orchestra. But perhaps our modern sensibilities were reading too much into one man's eccentricities.

The son of an alumnus, Hovey naturally attended Dartmouth. He waited a year before matriculating, but still, at age 17, he was the youngest member of the class of 1885. He loved the College, but bemoaned the endless winter. A Dartmouth professor, Allan Macdeonald, produced a biography of Hovey in 1957. Hovey, Macdonald wrote, found the New Hampshire cold unbearable. He thought, that first winter, of transferring closer to his home in D.C., to Johns Hopkins, but soon figured out the best maneuver was to simply stay away from Hanover as much as possible. Hovey extended all his winter holidays, leaving early in December and returning well after classes resumed in January. When he was forced to be in Hanover, he grimly cursed the gray skies and cutting wind. One letter Hovey wrote to his mother, in November 1884, made it clear he was not singing at the sight of the first snowfall: "Snow is on the ground now; no fields and hills and brooks to stray and rest and gladden in,—in such a situation, you see there is no relief."

Even alcohol, the usual restorer, was not a help. Macdonald records an incident at the annual mid-winter Freshman Beer, a night when the freshmen set up kegs at both ends of the third floor of Dartmouth Hall and invited upperclassmen to rotate up and down the hallway with mug in hand. Looking out the window, the revelers saw Hovey appear, "with a coffin he had purloined from the Medical College. Unsmilingly he slid downhill on this improvised toboggan, and then solemnly trudged up the hill again."

In a letter written from Hovey's mother to Hovey's cousin in February 1885, "Dick" had just left for Hanover, late again for the spring semester. "He dreaded to go back in the cold, for 'tis very cold up in N.H. and Dick don't like cold weather any better than I do....By the way I don't know what Dick has gone back to, for the students wrote him [that] there had been a burglar in his room during the vacation and had stolen all he had there. What the poor boy will do I don't know. He had a great deal of value there which it will not be easy for him to replace. He says he left there about five hundred dollars worth of books, beside all his furniture. We are anxious to hear from him and to know what his real loss is. Isn't it too bad when he is on his last year."

When I read that, I imagined Hovey disembarking at the Norwich station, defiant in his fancy clothes. He would have trudged across a covered Ledyard Bridge and up the steep, bitter hill. It was not snowing, but dark, and the icy road made him slip. He reached his room on the second floor of Reed Hall and saw his smashed furniture, empty bureau, books scattered. In the corner a window clattered, open to the drifting cold.

THIRTEEN YEARS AFTER GRADUATION, Hovey, in a stunning volte-face, publicly embraced the New Hampshire winter. Hovey had spent the interim years teaching at Columbia, hobnobbing with French literati in Paris and writing plays. In 1894, while living on Copley Square in Boston, Hovey penned a poem for the city's Dartmouth Lunch Club which became "Men of Dartmouth." But he never published a book of his own poetry until Along the Trail: A Book of Lyrics, which the copyright office entered for copyright on 12 December 1898. Inside were 59 poems. One was the "Hanover Winter Song." The frosting wolf-winds and the log fire, Hovey wrote, created a necessary frisson that led to the special Dartmouth camaraderie. In a way Hovey articulated the joys of the apres-ski life, the pleasure one gets, after a day skiing, of drinking around a warm fire with friends. It was what I like to call, after a Wendell Berry poem, the "how-exactly-good-it-is-to-melt" theory. Suffering becomes sweet when you come in from the cold. Freezing is memorable because of the thaw. The shower is better, the nap deeper, the beer tastier, and most of all, the conversation richer. No season can produce more suffering followed by more sweetness than a winter or four up in Hanover.

A hundred years ago this attitude was revolu- tionary, yet Dartmouth immediately absorbed the notion. Frederick Field Bullard, a Boston friend of Hovey's, set the poem to music and through-out that winter Dartmouth men . 'Ac crooned and yodeled the new song. In March 1899 the College asked the publisher to print a second edition. Two more edition appeared, in 1903 and 1908, making the book Hovey's best-seller, after the two Songs of Vagabondia. And suddenly Dartmouth men went outdoor Snowshoeing trips became common. mon. College men with wooden cross-country skis—some so long that they, like a tandem bicycle, had two sets of bindings-began schussing around the golf course. Around 1906 they started shoveling snow into mounds on Freshman Hill to Create little ski jumps, good enough for 20-foot leaps. Three years later 60 students attended the inaugural meeting of the Dartmouth Outing Club.

What made Hovey suddenly decide winter was not evil? Was the reversal caused by the pipe-freezing freezing winters he subsequently spent in Boston and London? Was it an extension of his aesthetic principles, that art creates reality? Was it a result of translating Mallarme, who argued that the artist must transpose the world into dream?

My theory is that Hovey had a perfect sense of humor. He loved to play the fool, to invert the usual standards. The most enduring legend of Hovey at Hanover, spread in newspapers and recounted at his wedding, was of a duel. A fellow 1885, Sam Hudson, criticized a poem of Hovey's, and the young poet challenged him to a duel to be fought at dawn in Norwich. Hudson, making the whole affair absurd, chose a cannon as his weapon. Hovey in reply named a sword. "Hovey," writes Macdonald, "seemingly determined to charge the cannon with his gallant weapon, made his farewells. Only Hudson's refusal to go on with the game called halt to the vivid fancy of the gentleman from Washington." It was this kind of man, who attacked cannons with a sword and sledded hills in a stolen coffin, who could summon the imaginative flair to change an attitude and reinvent a college's ethos.

SINGING THE "HANOVER WINTER SONG" at the sight of the season's first snowfall was not always my custom. Winter at Dartmouth had been exciting, no doubt. I got my first ice-cap there, when, after showering at the gym, I stepped outside and my wet hair froze into a helmet of crystal ice. Marching off to language drill one winter involved an almost daily tumble on the ice patch that formed each night on my dorm's front steps. But winter was also skiing along the roads on a snowy night, the street lamps blinking in the swirl as if the snowflakes were a thousand moths flying to the light. Winter was a carnival of sledding and snowballs through open windows. Winter was telemarking downMt. Cube. And everyone down south thought we were so brave.

Exactly one year after graduation I devised a ritual of remembrance, but it had nothing to do with winter. I had been thinking about that moment right after Commencement, after the caps had been thrown and the president had bid us not good-bye but farewell. We had slowly found our families and dispersed. I thought about how I'd stood on the steps of Dartmouth Hall and watched, while my father maneuvered the camera, as my class steadily broke into smaller and smaller pieces. In clumps and pairs, we had stepped off the Green, like water filling a plate and then slipping over the sides. We would never be together as an entire class again. Now, a year later, I was miles from Hanover .Sol wrote down a list of rituals I would perform each ninth of June, to remember and reconnect myself to the College. That year I saw the sun rise, sang the alma mater, wrote a letter to a classmate, wore a Dartmouth T-shirt, and read this magazine. As the years passed, though, I relinquished my Commencement-day rituals. I forgotthe date. I was too tired to get up at dawn. I was traveling without this magazine, without even a Dartmouth shirt. I needed a liturgy to remember the College and remember who I had been, but it had to subconsciously reconnect me to a more lasting aspect of my Dartmouth years. My ritual needed to be about December, not June.

One early winter afternoon I found myself calling my old roommate Taylor on the first day that it snowed. I did not mean to. It just happened. I could only recall one verse and the chorus, so I repeated the chorus until Taylor's machine ran out of room and hung up on me. Singing the "Hanover Winter Song" became more than an excuse to ring up an old friend. It was a way to say I still lived under the green man- tie of Dartmouth. I still welcomed the Norwegian ice-gnomes and the fire goblins. I still heard the sleigh bells. Another year had passed and I was returning, like all other women and men of Dartmouth, to the season that had made my college years come alive. White flecks again filled the sky and blanketed the earth, and my heart again was glad. Winter had come.

Richard Hovey

HOvey attackedcannons with asword, sledded in acoffin} andreinvented theCollege's ethos.

JAMES ZUG '91 is a book reviewer for Outside magazine and areader at The Paris Review.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

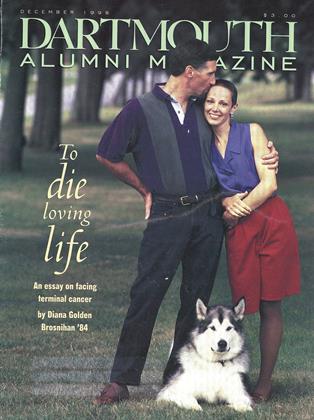

Cover Story

Cover StoryTo die loving life

December 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

December 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

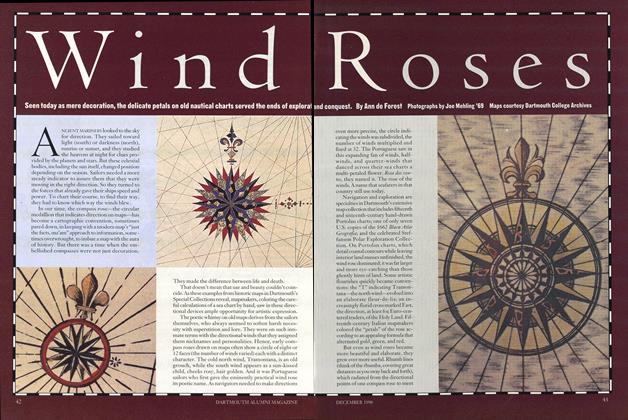

FeatureWind Roses

December 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Article

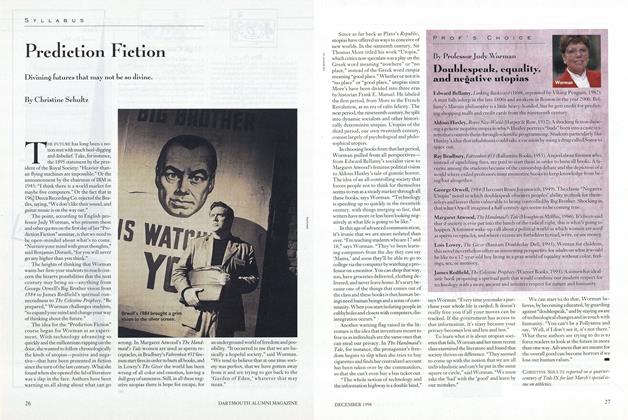

ArticlePrediction Fiction

December 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

December 1998 By Noel Perrin

James Zug '91

Features

-

Feature

Feature1923 – Great Class of a Great College

JULY 1973 By Charles J. Zimmerman '23 -

Feature

FeatureMR. SCHOLASTIC

FEBRUARY 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO QUIT YOUR JOB AND HIT THE OPEN ROAD (IN A MOTOR HOME)

Sept/Oct 2001 By MARIANNE McCARROLL 84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBusted By the Cryptic

MARCH 1995 By Valerie Frankel '87 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2007 By William Landmesser '74