How the poet came to sit on the road less traveled.

QUICK—who's the greatest writer ever to attend Dartmouth? Robert Frost, of course. No one else even comes close.

Second question: Where on campus can you find a statue of him? You don't know? What kind of poetry lover are you, anyway? This man is (a) your fellow alum, and (b) the author of about a quarter of the really famous lines of poetry (in English) that have been written in this century. And you can't find his statue?

True, Frost never said that the world would end not with a bang but a whimper, like sad Mr. Eliot. Fie had a far more dramatic prophecy. Here's the whole small, perfect poem.

Some say the world will end in fire,Some say in ice.From what I've tasted of desire I hold with those who favor fire.But if it had to perish twice,I think I know enough of hateTo say that for destruction iceIs also greatAnd would suffice.

Neither did Frost observe, like Yeats, any rough beast slouching toward Bethlehem to be born. But he wrote an equally famous perhaps more famous, travel line. "Two roads diverged in a yellow wood," it begins—and I'll bet that even former chemistry majors know what words come next.

So why is the statue of Frost so hard to find? There's a story here, a road-less-trav-eled story. It begins back in 1990, when a member of the class of 1961 offered to give the College a bronze statue of the one alum who is clearly a greater man than Frost. I mean, of course, Daniel Webster.

The College's acquisitions committee turned the offer down, in large part because its members said they felt a "lack of confidence" in the sculptor who would have gotten the commission. Two years later a considerable number of'6ls joined the original would-be donor in offering the College a statue by a different sculptor of a different person: Frost.

This time the College accepted—though not without a good bit of turmoil, both on the acquisitions committee (which includes representatives from four academic departments, the director of the Hood Museum, and soon) and even within the class of'61. For example, there happens to be a prominent sculptor in the class, a non-representationalist who couldn't possibly have wanted the commission for himself. It was in a perfectly disinterested way that he described the proposed statue as "calendar art kitsch."

He had a point, too. I love the Frost statue—in part because I love Frost himself— but I do recognize that George Lundeen, the chosen sculptor, runs a sort of sculpture factory in Loveland, Colorado, and is capable of sentimentality. That doesn't keep me from taking pleasure in the way Lundeen sculpted Frost's head, not to mention the folds of cloth of Frost's shirt—pleasure I find in very few of the abstract sculptures around campus.

Back to the story. The acquisitions committee accepted the sculpture. They then had to find a home for it. One suggestion was to put it on the Green, another to place it on the arcade between Sanborn House and Baker Library. In the end, they planted it quietly in the woods up near Bartlett Tower, where it would be inconspicuous. When some '6ls asked if there could be a sign directing people to it, the head of the acquisitions committee replied, "I regret to say that this will not be possible." The College, he went on to explain, has a long-standing, campus-wide policy of few signs and no guideposts.

And that's why you don't know where the statue of Dartmouth's greatest poet is.

I have to add one more tiling, though. Except for that one detail, this is a happy ending. The acquisitions committee may have sequestered the Frost statue because cause they think it's sentimental kitsch. But they did just right. The statue actually looks better up in the pines than it would have on the Green or in the Sanborn arcade. It is even right that Frost, that veteran disappearer should be facing away from campus as he sits writing a poem.

The only thing that isn't right is the bronze line of verse you can read on his bronze pad. Oh, it's a famous line, all right. "Something there is that doesn't love a wall." But there's nothing apt about it. What he should be writing, as he looks through the tall pines above the Bema is an equally famous and very relevant line: "Whose woods these are I think I know." These are Dartmouth's woods, now haunted by Dartmouth's greatest poet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

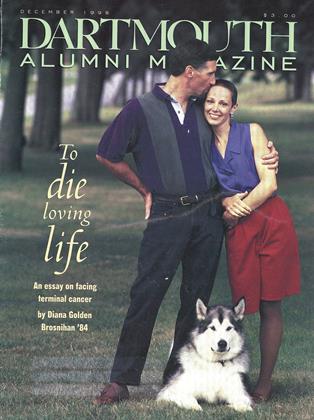

Cover StoryTo die loving life

December 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

FeatureHere by the Fire

December 1998 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

December 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

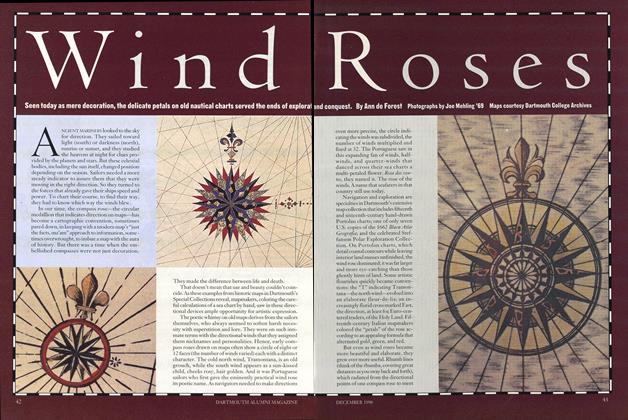

FeatureWind Roses

December 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Article

ArticlePrediction Fiction

December 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MARCH 1971 -

Article

ArticleMinor Issues

MAY 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Cubicle of One's Own

JUNE 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

NOVEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Lottery Where Everyone Wins

APRIL 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

MAY 2000 By Noel Perrin

Article

-

Article

ArticleInter-American Conference

November 1940 -

Article

Article"Perfectly fascinating"

NOVEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleEnglish Professor Lynda Boose: What is meant by the Expression to "Bridle one's Tongue"?

MAY 1996 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

APRIL 1999 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth-on-the-Pacific Conference

November 1955 By EDWIN J, DRECHSEL '36 -

Article

ArticleTHE 1947 ALUMNI FUND

February 1948 By RICHARD A. HOLTON '18