So what if the hiring of director MaxwellAnderson '77 created a buzz in the NewYork art world? The real question is: cana little-known classicist restore lustre to afading museum of contemporary art?

A FEW WEEKS AFTER David Ross resigned from his position as director of the Whitney Museum of American Art in March 1998, the chairman of the museum's board of trustees, Leonard Lauder, told a New York Times reporter that he wanted his next hire to be a "superman" a curator, administrator, and fundraiser combined "who can lead the museum and the staff and the trustees and the art world to greatness."

Four months later, Lauder named Maxwell Anderson '77 to the post. With the accolades and high praise that are to be expected at these events, Lauder noted that "Max has the proven ability to integrate the demands that directors face today. He is a strong leader who understands how to maintain a dynamic balance between the public and scholarly roles of a museum." But the public proved a harder sell. Although Hilton Kramer, a conservative art critic and editor of The New Criterion, praised Anderson's scholarship in classical Greek and Roman art history, curators, collectors, and gallery owners simply yawned. "I don't know who you're talking about," said gallery owner Paula Cooper to a New York magazine reporter. "Did he die or what?"

Ouch. But after all, the Whitney is in New York, a city that architect Frank Lloyd Wright called, "the biggest mouth in the world" for its ability to chew people up and spit them out. Although he is a native, having been born and raised near Columbia University where his father, Quentin Anderson '35, was a professor of American literature, Max Anderson had as much as dropped off the earth for 12 years, running museums in Atlanta and Toronto. During that time, the Whitney, always a controversial museum awkwardly balancing a historical view of American art with surveys of living American artists, managed to alienate both the conservatives and the avant garde.

"It's hard to say precisely when," wrote The New YorkTimes chief art critic Michael Kimmelman, "but several years ago the Whitney Museum pretty much slipped off the radar screen. Arguing about it had been a cherished pastime, then people seemed to stop talking, or really caring, about it as they once had." In fact, average annual attennual attendance over the last decade has remained close to 300,000, less than a third that of its competitors, the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. And while the Guggenheim made a splash by creating a stunning new Frank Gehry-designed, titanium outpost in Bilbao, Spain, and the MoMA announced plans to demolish several nearby properties so that it could increase its gallery space, the Whitney chose to quietly expand from within by converting administrative offices into galleries and moving the staff into adjoining townhouses.

In this context, then, Anderson's low profile could actually be a good thing. He has never had to publicly side with the art conservatives or the cutting edge. And he was far removed from fiascoes such as the 1993 Whitney Biennial, the museum's signature show which features works made in America in the preceding two years. That exhibition, dubbed the "Political Show" by critics, featured works such as a videotape of the Rodney King beating and synthetic vomit on the floor as a statement on bulimia. "The Whitney became so bloody politicized, every time you went, you felt guilty about some cause," says professor Robert McGrath, chairman of Dartmouth's art history department.

Meanwhile, since Anderson's previous positions were as director of a university museum, the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory, and a Canadian one, the Art Gallery of Ontario, as well as curator of Greek and Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he had few, if any, public allegiances to contemporary American art or artists. "He has no enemies that I know of, and he has no friends," said gallery owner Holly Solomon in that New York article. "In other words, he's got the freedom and the power to make his mark without any rancor or prejudgment."

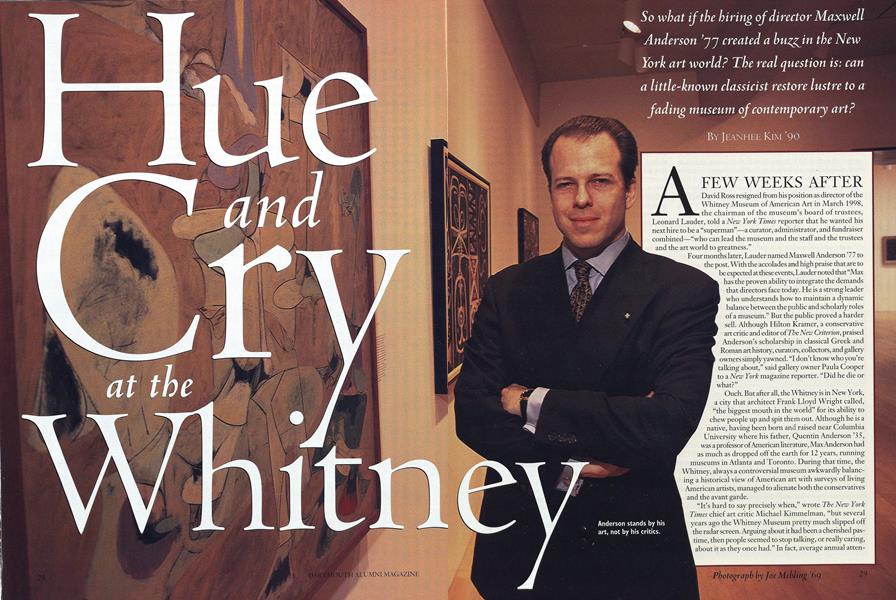

A COMMON REACTION to Anderson's appointment is: What's a classicist doing running the twentieth century-focused Whitney? "It's an unfortunate assumption," says Anderson, from his bright and orderly office. "I'm an art historian but I live in the present. All of my education has been broadly in the history of art, including contemporary." A clean-cut, boyish-looking man in a conservatively tailored suit, Anderson, 42, speaks authoritatively and assuredly, neither inviting debate nor raising his voice. Clearly, however, this question annoys him. He reels off the names of museum directors across the country whose jobs do not reflect their academic specialties. Most prominent among them is Glenn Lowry, director of the MoMA, who is an Islamicist. "People have yet to look broadly at the profession; there are very few directors who curate."

As has many a freshman, Anderson was turned on to art history by a survey course, Dartmouth's Art History 101. "It prompted me to see how the visual arts were an extraordinary place that connected ideas, objects, history, and social concerns the way no other field could," Anderson says. Since he had grown up in New York City and always liked museums, these two interests dovetailed and he "got the bug." He distinguished himself as a talented and brilliant student, and especially one who was self-directed. In his sophomore year, Anderson approached Jan van der Marck, then the director of Dartmouth's galleries, and proposed a museum internship, even though neither a museum nor an internship program existed. With Vandermark's blessing, he wrote labels for the paintings and sculptures that hung in the Hop, and composed the text for pamphlets distributed in the gallery space.

As a sophomore, Anderson wrote a paper published in the Print Review, under encouragement from art history professor Frank Robinson. "His scholarly writing showed that he responded to the original work of art, and that's vital. That's what museum work is all about," says Robinson, now the director of Cornell's Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. Anderson also won the Adelbert Ames Fine Art Award as a junior and shared the William B. Jaffe Art History Award as a senior. About the only setback that Anderson experienced was when, as a junior, he was rejected from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's summer internship program. "I was crestfallen. I thought this was the end and I might as well go to law school," says Anderson. But with encouragement from professors McGrath, Joy Kenseth, and John Wilmerding (who gave Anderson an anomalous C+, in, ironically, a class on twentieth-century art), he reapplied the following year and was accepted into the program for the summer after graduation. Kenseth recalls how, in the evenings or late afternoons of his senior year, on breaks from working on his thesis, "Max would stroll into the slide room, sit down, and talk about his plans. He was so focused, he knew early on exactly what he wanted to do."

That fall Anderson went to Harvard where, in just four years, he received his M.A. and Ph.D. in Greek and Roman classical art history. Then he rejoined the staff of the Met as an assistant curator in 1981. He stayed for five years before he set his sights on becoming a museum director, where he could "connect intellectual resolve with a public purpose."

It was while running the two museums that Anderson built the resume of skills and experience that made him so attractive to the Whitney's trustees. At Emory's Carlos Museum, he quintupled die staff, doubled its art collections, and encouraged numerous international exhibitions. He also planned, funded, and oversaw a major expansion of the physical space by architect Michael Graves. Anderson took a leading position in bringing museums into the computer age, too. The Carlos was one of the first museums to place computer kiosks in its galleries to supplement the printed information on the walls. And Anderson founded the Art Museum Image Consortium, putting more than 20,000 images from 26 member museums onto the Internet for use by institutions, scholars, and students. Just as importantly in the modern museum world, Anderson became known as a skillful schmoozer, able to elicit major donations of art work and funds. He sharpened these skills while at the Art Gallery of Ontario, a museum twice the size of the Whitney. In 1997 alone he attracted $74 million in art donations. "We were impressed by his experience, his accomplishments, his social skills, and his ability to be far-thinking and to see into the future," says Whitney trustee Lauder.

ANDERSON'S BIGGEST challenge remains to impose a strong and unique identity on the Whitney, whose turf is threatened by museums like the MoMA, which recently merged with contemporary art space P.S. 1, and by the Guggenheim. In his first five months, Anderson made several changes that long-ignored conservatives found heartening. Instead of the former free-form responsibilities of the curatorial staff, which many believed allowed the staff to be overweighted with contemporists, Anderson made each curator responsible for a particular period or medium of art, such as pre-World War II, or film and video. Dedicating two of the Whitney's five floors of gallery space to exhibiting the permanent collection, Anderson, unlike his predecessors, has shown a commitment to keeping the Whitney's historical collection on public view. "I'd like the Whitney to be fertile ground for considering the very best in American contemporary art, and assessing the contribution of American artists over the last century. It has to do both, almost in equal measures," Anderson says.

As a result of these decisions, three curators and one trustee all associated with more cutting-edge art have resigned from the museum. This caused a buzz in the press, and cheers from conservatives. "Another score for Anderson," said Hilton Kramer, "he gets to fill another slot with staff that is more accountable to the standards that he will set."

But these signs do not point necessarily to a conservative new Whitney. By all accounts Anderson is committed to contemporary art. The museum's newest acquisitions include a room-size art video installation, a digital photograph, and a film. "I look to artists to clarify some of the issues that dog us in daily life, to see beyond the flotsam and jetsam of commercial mass media. That will only happen in video, installation art, painting, and film. It won't be a single course or direction."

The 2000 Whitney Biennial next March will be Anderson's first major public test. The Biennial, a concept that started two years after Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney founded the museum in 1930, has long been "a hot-button show," according to The NewYork Times. Critics have called it "the art world's punching bag." Anderson has already got people talking about it. He recently announced that, for the first time in the museum's history, the Biennial will be organized by a team of curators from outside the Whitney. He says he has drawn perspectives from around the country to broaden a show that has been criticized for being cliquish and New York-centric. One of the regional curators on the team, Michael Auping of the Modern Art Musem of Fort Worth, acknowledges the challenge Anderson faces in pulling off a major exhibit-by-committee: "It's a very loaded situation when you have a new director who is still the whipping boy, when the Biennial is the show everyone loves to hate, and when it's the 2000 Biennial. It's almost a caricature of the worst possible Biennial scenarios."

For those looking for earlier signs of Anderson's influence, a hint can be found in Part II of "The American Century," a retrospective of American art since 1900 and the largest exhibition ever planned at the Whitney. For the October opening (Part I opened in April), Anderson and his staff have been working closely with computer chip maker Intel to develop a hand-held video and audio device that can accompany people as they move through the exhibition. "I'm walking into this project with great cautiousness," explains Anderson. "But I'm persuaded that a younger generation will expect it of us."

Time will tell whether Anderson succeeds in forging a strong identity for the Whitney. Two things seem clear so far, however. One, if Anderson does get good reviews, it will be in spite of the art critics, and not because of them. Critics, he says, practice "the tea leaves school of journalism, seeing one thing and trying to make it mean something." He prefers the counsel of peers and artists. Two, that whether by design or luck, the departures of several staffers may have blunted a museum director's biggest threat: political infighting. Friends think that of all Anderson's attributes, his ability to navigate social and political thickets is paramount. "Max is a diplomat, not a politician," says McGrath. Which, here, is probably a good thing. As McGrath notes, "The Whitney will devour anyone who cannot be perceived as rising above the fray."

Anderson stands by his art, not by his critics.

"He has no enemies, and he has no friends. He's got the freedom and the power to make his mark without any rancor or prejudgment."

JEANHEE KIM, a former intern at the Guggenheim Museum inNew York and Italy, is an editorial producer at Oxygen Media. Onher first visit to the Whitney, at age 13, she saw a topless woman playa cello made from a tv set, a stick, and a string.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

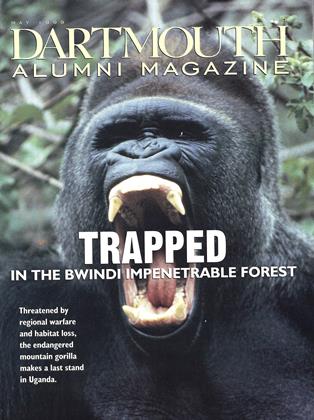

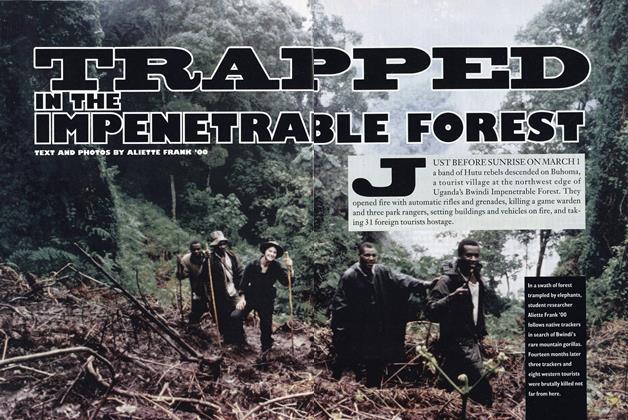

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

May 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

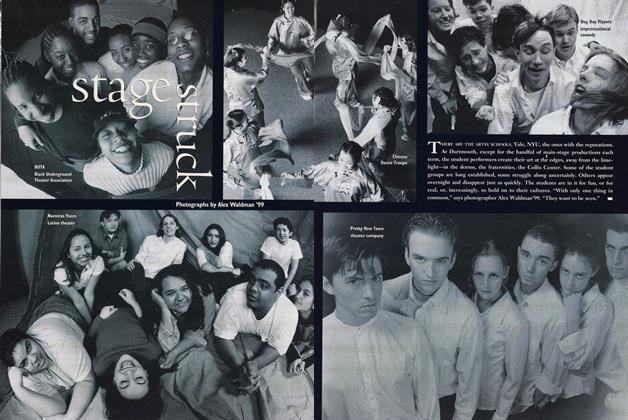

FeatureStage Struck

May 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

May 1999 By Don O'Neill -

Article

ArticleThe Financing Game

May 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Masculine Mystique

May 1999 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

May 1999 By James Wright

Jeanhee Kim '90

Features

-

Feature

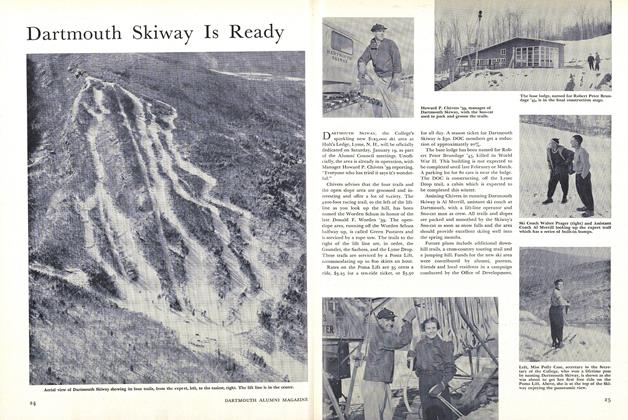

FeatureDartmouth Skiway Is Ready

January 1957 -

Feature

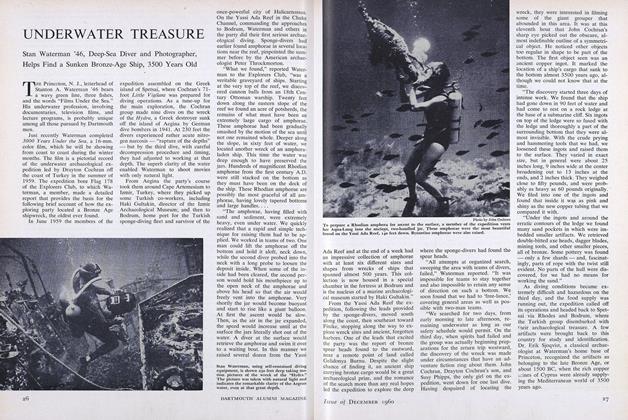

FeatureUNDERWATER TREASURE

December 1960 -

Feature

FeaturePolice Commissioner

JANUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

DECEMBER 1970 -

Feature

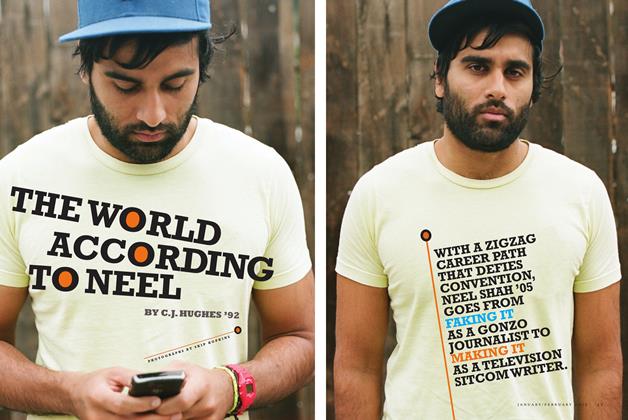

FeatureThe World According to Neel

Jan/Feb 2012 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureLOG DRIVE

JUNE 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58