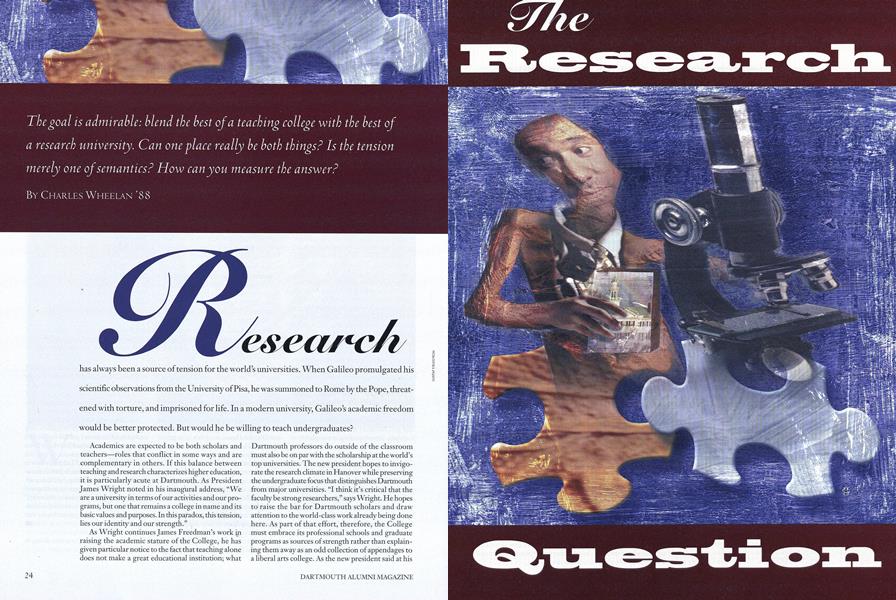

Research has always been a source of tension for the world's universities. When Galileo promulgated his scientific observations from the University of Pisa, he was summoned to Rome by the Pope, threatened with torture, and imprisoned for life. In a modern university, Galileo's academic freedom would be better protected. But would he be willing to teach undergraduates?

Academics are expected to be both scholars and teachers—roles that conflict in some ways and are complementary in others. If this balance between teaching and research characterizes higher education, it is particularly acute at Dartmouth. As President James Wright noted in his inaugural address, "We are a university in terms of our activities and our programs, but one that remains a college in name and its basic values and purposes. In this paradox, this tension, lies our identity and our strength."

Dartmouth professors do outside of the classroom must also be on par with the scholarship at the world's top universities. The new president hopes to invigorate the research climate in Hanover while preserving the undergraduate focus that distinguishes Dartmouth from major universities. "I think it's critical that the faculty be strong researchers," says Wright. He hopes to raise the bar for Dartmouth scholars and draw attention to the world-class work already being done here. As part of that effort, therefore, the College must embrace its professional schools and graduate programs as sources of strength rather than explaining them away as an odd collection of appendages to a liberal arts college. As the new president said at his As Wright continues James Freedman's work in raising the academic stature of the College, he has given particular notice to the fact that teaching alone does not make a great educational institution; what inauguration, "Dartmouth College is a university in all but name."

Research is the Indian symbol of academic issues at Dartmouth; it immediately raises the hackles of alumni and even of some faculty. Their fear is straightforward: students should not play second fiddle to laboratories, journal articles, and international conferences. Dartm outh will never be Harvard or Berkeley, and it might sacrifice what is special about the place in the process of trying. Research and teaching may be natural siblings, but many students come to Hanover because they prefer to be treated like only children. "Dartmouth students have an extraordinarily high expectation of service," notes one alumnus.

Yet most academics find the alleged tradeoff between teaching and research misplaced, or even silly. Research informs teaching, keeping it fresh and relevant. The plodding reputation of the academy notwithstanding, fields of discipline can evolve quite rapidly. In a decade or two, a field can be transformed entirely. Those in the economics department speak in hushed tones about a long-standing professor—a favorite of alumni—who was teaching outdated material by the end of his career. He had simply fallen out of touch with key parts of the discipline. What Dartmouth alumnus would visit a tax lawyer who had not restocked his human capital in 15 years? Or a heart surgeon? Dean of the faculty Edward Berger paraphrases a peer at Harvard: "If I am deciding between two faculty members, give me the stronger researcher. The other person will be teaching the same stuff in 20 years."

Both views of teaching and research are rooted in truth; both are also facile in some respects. Good researchers can be extraordinary teachers. They can also mumble incoherently to themselves at the chalkboard. This writer, having spent more years in graduate school than he would care to enumerate, has had some of each. Gary Becker, the Nobel Prize winner in economics, still teaches several courses a year at the University of Chicago. He can hold a lecture hall rapt, in part because he punctuates his lectures with questions that the field's top scholars have not yet resolved. His students share the exhilaration of prob- ing the frontier of knowledge with one of the world's great thinkers. His teaching method is Socratic; he puts on his reading glasses and consults the class list. He looks up slowly, "Mr. Wheelan...." This is not merely a performance; Gary Becker grades his own final exams.

But one of his Chicago colleagues, a brilliant researcher who sits atop an empire of nearly 50 graduate students, is so disorganized in the lecture hall that he often neglects to erase the chalkboard after it has been filled. Instead, he returns to the top of the board and begins writing between the lines, making it virtually impossible to read anything. (Not that most students understand what he is writing, anyway.) He has, on occasion, been known to write equations on the wall when nothing more can be squeezed onto the blackboard.

Some great thinkers can teach; others cannot. But even among good teachers, logic suggests that in a world of scarce resources, teaching and research must be at odds with one another on some level. There are only so many hours in the day. A researcher who is putting the finishing touches on an article for a top journal is probably not answering student e-mails. "If you look at the people winning the national prizes in the sciences, those are not the people holding office hours every week," says Jane Lipson, an associate professor of chemistry at Dartmouth. Some prestigious research grants take scholars away from campus, leaving students with adjunct replacements. Indeed, one common medium of exchange at leading research institutions is the teaching release. Scholars doing high-level work or earning extensive outside funding are rewarded with fewer teaching obligations.

And certainly nothing about the training of academics at major universities suggests that teaching is equal in importance to research. This writer's doctoral training did not offer a single course, seminar, video, or pamphlet on effective teaching. Yet I was responsible for students in seven different classes. At least I am fluent in English; some of my fellow teaching assistants were not. My dissertation advisor did offer one a pearl of teaching wisdom. He noted sagely, "The difference between giving a student a B-and a C+ is about half an hour of your time." The implication was that the student who gets the B won't trackyou down to complain. The most brilliant of academics can be dismissive of students, or even resentful of them.

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching recently drew attention to the state of undergraduate teaching. In a scathing report, a commission appointed by the Foundation noted:

The research universities have too often failed, and continueto fail, their undergraduate populations. Tuition income fromundergraduates is one ofthe major sources ofuniversity income,helping to support research programs and graduate education, but the students paying tuition get, in all too many cases,less than their money J worth.

Indeed, it is ironic that while Dartmouth reexamines the role of scholarship, other elite institutes are rediscovering undergraduate education.

Will Jim Wright's plan to elevate the level of scholarship at Dartmouth further burnish the image of the College? Or will it lead us into a minefield the rest of higher education is trying to escape? The answer is most likely the former, but the new president will have to steer carefully and persuade many doubters along the way.

THERE IS AN IMPORTANT distinction in the Carnegie Report that speaks directly to Jim Wright's plans. The report did not criticize faculty research; rather, it noted that all too often undergraduates are completely uninvolved in such work. The report noted, "Recruitment materials display proudly the world-famous professors, the splendid facilities and the groundbreaking research that goes on within them, but thousands of students graduate without ever seeing the world-famous professors or tasting genuine research."

The Dartmouth faculty who speak most enthusiastically about research believe unequivocally that their students are the beneficiaries. Professional expertise can and should provide experiences that enliven the classroom, insists Linda Fowler, a government professor and a Congressional scholar. "I do fine on the Supreme Court, but that's not where my good lectures are," she says. Fowler, who is also director of the College's Rockefeller Center, visited the U.S.S.R. in 1987 as part of a delegation of political scientists hoping to generate a dialogue on how to create a democratic society. In 1997 she was invited to be an outside observer for the orientation of newly-elected House members. "You don't get invited to do these things if you're not a visible scholar," she says.

The faculty-student relationship can work in the other direction as well. Teaching can help to focus a research problem, or at least provide some relief. "It's intellectually rejuvenating sometimes," says Dan Rockmore, an associate professor jointly appointed in mathematics and computer science. Undergraduates have little patience for ivory tower research; their pragmatic questions can keep a researcher from "wandering down a garden path," notes George Wolford, a professor of psychology and former dean who has been at Dartmouth for 31 years. He points out that at professional conferences, there is a noticeable difference in the clarity and focus of presentations between those who teach undergraduates and those who don't.

Jim Wright offers the computer science department as a model of how faculty research can be used to en-hance the undergraduate experience. Every year the Computing Research Association honors an outstanding male and female undergraduate in the field. The competition includes Harvard, Berkeley, the University of Chicago—all of the major research universities. In 1998-99 both the male and female winners were Dartmouth '99s. (The female winner, April Rasala, was also an All-Ivy soccer player.) "We take the best undergraduates and treat them, at least intellectually, like grad students," says Dan Rockmore.

For those not persuaded by the sheer joy of generating knowledge, there are tangible benefits to all this. The essential skills demanded of graduates are increasingly research-related: framing a problem, thinking ically, gathering data, discounting bad sources, and conveying results clearly.

Research, of course, is not just about students. To faculty, Wright's comments mean more resources for attracting top people to Dartmouth and retaining them once they arrive. The economics department was able to make several high-profile senior hires because the department had shown a commitment to top research and had built a cadre of nationally-recognized scholars. If the market is any judge, students have not suffered. The number of students majoring in economics has climbed steadily. Economics continues to be one of the most popular majors at the College, despite a reputation for rigor.

Most Dartmouth faculty members were trained at top universities and hope to continue working at that level. "When I came here, there wasn't a sense that I was going to start doing research at a Dartmouth level rather than a Columbia level or a Harvard level," says Dan Rockmore, who was one of 15 American scientists in 1995 to receive a Presidential Faculty Fellowship Award from President Clinton for excellence in scientific research and teaching. Rockmore hopes that the heightened focus on research will allow the mathematics department to slightly expand its graduate program. Breakthroughs in mathematics—and many other disciplines—do not come by working alone behind a closed office door; progress demands interaction with other faculty members and graduate students. "There is a question of critical mass in mathematics," Rockmore explains. In short, the more great minds meeting around the water cooler the better.

One hears similar comments in other departments. "We're committed to being a topflight psychology department," says George Wolford. Resources help. The department will soon acquire an fMRI device—a functional magnetic resonance imager, which enables researchers to watch the brain at work. Such research is at the cutting edge of the discipline. No longer will Dartmouth brain scientists have to do their work late at night at Dartmouth- Hitchcock Hospital when the fMRI device is not being used to examine patients.

Some faculty point out that Wright's emphasis on scholarship will provide the impetus to improve weaker departments and make the Dartmouth environment less comfortable for tenured faculty who have gone years without doing any productive work. The promotion from associate professor to fall professor is based almost entirely on scholarship, and some faculty members never make the grade. "We have people in the institution who have been associate professors for 25 years," notes history professor J ere Daniell '55. According to dean of the faculty Edward Berger, there are roughly a dozen faculty members who have been associates for longer than seven years. To Daniell, a veteran of the Dartmouth faculty, elevating the level of faculty scholarship will only enhance Dartmouth's unique appeal. "Dartmouth is a, or the—depending on how arrogant you want to be—premier undergraduate liberal arts university," he argues.

His sanguine outlook is not shared by all. The chemistry department has produced national leaders such as Walter Stockmeyer while remaining focused on quality undergraduate teaching. Will junior faculty be forced to chase those national awards and sources of funding which, albeit prestigious, would take them away from teaching for as long as three years? Jane Lipson asks, "Will chemistry make those decisions, or will those decisions be imposed on us?"

ED BERGER TALKS ABOUT teaching and research at Dartmouth as a "blending, not an either-or." President Wright describes the balance between teaching and research as "a terribly important center that is more important than the midpoint." For all the talk about research, though, one of the president's most obvious gestures speaks to the importance of teaching. He has continued to teach a history course despite his move to Parkhurst. "I'm certainly not unaware of the symbolic value of my teaching," he says. "But I have to say that it's something that I've gotten tremendous satisfaction out of over the years."

The president has inherited an institutional culture in which undergraduate education is highly valued. Dartmouth's reputation for teaching determines who comes to Hanover in the first place and who chooses to stay. "What generally happens is that people who just can't hack it in the classroom leave before they come up for tenure," notes Jere Daniell. But nothing is more important in determining the role of teaching than the weight it gets in the tenure process. If operating a university is like steering an oil tanker, then the tenure process is the engine room. Tenure decisions determine who is asked to leave the college and who will be invited to stay for the rest of their professional lives. "Ail kinds of institutions talk about balancing research and teaching, but unless the tenure process takes both into account, it's all hp service," says Lipson.

According to a recent study by the Center for Instructional Development at Syracuse University, administrators at 11 major research universities reported that more emphasis was being given to teaching than five years ago. Yet the same group said that research productivity was still given "much more" weight in making promotion and tenure decisions than was teaching effectiveness. Dartmouth has become a preeminent undergraduate institution in large part because teaching matters in the tenure decision. [See sidebar, page 27.] A candidate's peers are contacted to determine his or her academic prowess; the candidate's former students are also contacted to evaluate his or her teaching ability. By all accounts, that teaching input matters greatly. "Dartmouth is certainly the only institution that I know of that so systematically develops a teaching evaluation portfolio for tenure decisions," says Ed Berger. Indeed, the willingness to turn away top scholars with no interest or talent in the classroom makes Dartmouth nearly unique. As Linda Fowler notes, "I don't think you can be a mediocre scholar and get tenure here, but being excellent won't guarantee it." George Wolford relates the story of a leading researcher in psychology who came to Dartmouth but refused to give any attention to teaching. "He just didn't care," recalls Wolford. The eminent scholar, who later received tenure offers from Yale and Northwestern and is now a member of the National Academy of Sciences, was not reappointed after his first three-year contract.

Do Jim Wright's comments signal a shift in the weight that teaching and research will be given in the tenure process? The new president does not envision an institutional tradeoff. "I think we can insist on having a research faculty that is committed to undergraduate teaching—and really gets satisfaction from it," he says. Still, junior faculty members will be studying tenure decisions much like Kremlinologists used to study the seating arrangement at the May Day parades. "The information is diffuse, unreliable, and there isn't very much of it," says one concerned faculty member. Meanwhile, alumni will be looking for any hint that Dartmouth has fallen into the dreaded orbit of Cambridge. Wright, first and foremost an historian, is not troubled by the ambiguity between teaching and research or the institutional debate it has inspired. Will Dartmouth be wrestling with the same issue in 50 years? "I think so," says President Wright. "I hope so. I would be troubled if it were ever resolved."

The goal is admirable: blend the best of a teaching college with the best ofa research university. Can one place really be both things? Is the tensionmerely one of semantics? How can you measure the answer?

Dartmouth garnered about $78 million in research funding in fiscal year 1998. Nearly three-quarters of the total was brought in by the medical school.

Research is the Indian symbol of academic issuesat Dartmouth; it immediately raises the hacklesof alumni and even of some faculty.

The Road to Tenure Few professions have such a rigorous process for judging their own. A faculty member at Dartmouth can apply for tenure only once, usually in the sixth year of service. With input from the candidate and the department, the associate dean in the relevant division compiles a list of outside scholars in the candidate's field who are invited to write a letter assessing the candidate's academic accomplishments. "One bad letter can be finessed; more than one is death," says Linda Fowler of the government department. Meanwhile, approximately 80 letters are sent out to a randomly-generated list of alumni who have taken a class or classes from the tenure candidate. The applicant can also list an additional four or five students "especially qualified to speak about his or her teaching." These students are asked to assess the teaching ability of the candidate. (Grades are noted, so that disgruntled students are not given a chance to exact revenge.) Based on this portfolio, which takes roughly six months to gather, the tenured members of a department vote for or against recommending tenure for the candidate. This vote is merely advisory, however. The decision then goes to the Committee Advisory to the President (CAP), a body elected by the faculty plus the dean of the faculty. The president attends the meetings but does not vote. The CAP decides for or against tenure, a decision that must then be affirmed by the president of the College and by the Board ofTrustees. Over the past decade, roughly two-thirds of candidates proposed for tenure have been granted tenure, though the real success rate is lower since many candidates likely to be denied choose to leave before a decision is made. -C.W.

The Going Rate for Professors Research is the lifeblood of scholarship. As an incentive to bring the best scholars to Hanover (and to keep them once they get here) Dartmouth has assembled an attractive package of financial incentives. All new faculty are given a $15,000 Burke Grant, which is available for research within the first three years. This is a very useful recruitment tool. According to faculty dean Ed Berger, few colleges guarantee that kind of money to all new professors regardless of discipline. In addition to the Burke Grant, new faculty may apply for College grants that can reach the $200,000 level, depending on the individual project. All faculty get $1,500 a year for research. In addition, because Dartmouth pays professors for three out of the four annual terms, faculty can boost their annual salary by winning a research grant for that fourth term thereby providing them with what is known as a "summer salary."

"We take the best undergraduates and treat them,at least intellectually, like grad students " saysmath professor Dan Rockmore.

CHARLES WHEELAN holds amaster's degree in public affairsfrom Princeton's WoodrowWilson School and a Ph.D. inpublic policy from the University of Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

October 1999 By Sarah Messer -

Feature

FeatureMoosilauke's Mad Historian

October 1999 By Viva Hardigg '84 -

Article

ArticleStories on Rye

October 1999 By Tamar Schreihman '90 -

Article

ArticleTeamwork

October 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

October 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1999 By Leslie A. Davis Dahl, John MacManus, Shelley L. Nadel

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

JUNE 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Interview

Interview“A Privileged Position”

Nov/Dec 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionDollars and Sense

Jan/Feb 2004 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Interview

Interview“Look Globally”

Mar/Apr 2006 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleReel Economics

September | October 2013 By Charles Wheelan ’88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMatthew Wysocki Professor of Art 300 St. Nicks in D single collection

January 1975 -

FEATURE

FEATUREFly Boy

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Cover Story

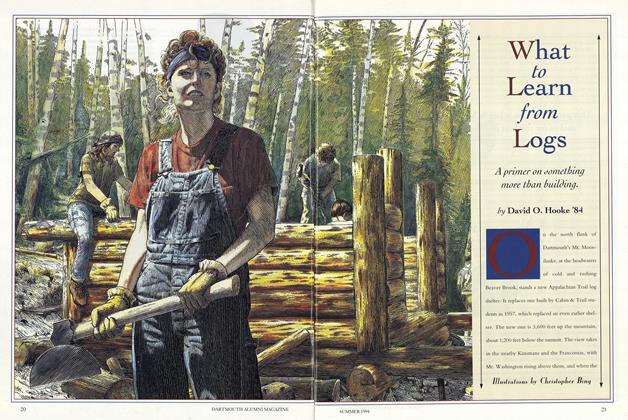

Cover StoryWhat To Learn From Logs

June 1994 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2007 By William Landmesser '74