They’re Off The Mark

Opponents of global trade—like those at the WTO meeting in Seattle last year—have got it all wrong.

Nov/Dec 2000 Matthew SlaughterOpponents of global trade—like those at the WTO meeting in Seattle last year—have got it all wrong.

Nov/Dec 2000 Matthew SlaughterOpponents of global trade—like those at the WTO meeting in Seattle last year—have got it all wrong.

PEOPLE EVERYWHERE—IN THE United States and especially abroadhave a right to feel worried about the distorted picture of global trade that emerged from last Novembers meeting of the World Trade Organization in Seattle.

Protesters did their best to portray the WTO as a conspiracy of greedy corporations while presenting themselves as valiant citizens struggling to promote happiness throughout the world. Protesters focused on a variety of issues-changes in American jobs, working standards abroad, the environment— but were unified in their belief that, on balance, the WTO represents something bad.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The WTO was founded in 1995 as the successor to the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs that was established in 1945. The goal of the WTO s 135 member nations is to improve living standards everywhere—in rich and poor countries alike. The keyword here is "everywhere." Trade and foreign direct investment (major U.S. investment in foreign businesses) generally improve average living standards in all countries involved. This is a win-win situation, not win-lose.

That said, these average gains usually entail redistributions of income, with some groups hurt by the liberalization of trade and foreign direct investment, at least in the short-term. These issues of reallocation of income and employment drive much of the opposition to globalization. But what is disturbing is how the policy discussions about trade and foreign direct investment focus on the redistribution and completely bypass the aggregate gains.

Think of technological progress. It works just like trade does: both raise living standards through a dynamic process, with winners and losers along the way. Take ATM machines. Their clear benefits have come at a huge cost to thousands of workers in the banking industry. ATM machines have probably "destroyed" more U.S. jobs than most trade agreements. Why don't WTO opponents decry the besieged bank tellers? Because people understand that the benefits of technology require dynamic change. Why not for globalization, too?

A big part of the problem is marketing. Many WTO opponents trumpet how many American jobs trade destroys. In response, many WTO supporters scramble to count how many American jobs trade creates. This strategy is a sure loser. Just like technology, trade and foreign direct investment both destroy and create jobs. The issue is not the number of jobs, it's the kind of jobs. Unfortunately, these crucial ideas were lost in Seattle amidst the broken windows and tear gas.

Proof of the power of freer trade and investment comes in a couple of flavors. One is the consensus of professional economists. We all know the old saws about how economists love to hem and haw. Yes, economists sharply disagree about a lot of policy issues. Should the federal government payoff its debt? What should monetary policy be? But surveys by economists of economists have repeatedly shown that the one issue upon which nearly all economists agree is the benefits of free trade. There is no sharp professional disagreement on this issue.

An even more compelling argument for globalization can be found in the clear preferences of the poorest countries in the world. China, India and a host of other poor nations were furious over the Seattle debacle. For decades these countries pursued inwardlooking economic policies which largely delivered economic stagnation—and environmental degradation. The world's most egregious environmental disasters lie in the former Communist countries. Today, these countries understand that the post-World War II economic "miracles"--Japan, South Korea, Taiwan—focused on a global market.There are literally billions of people on the Earth today who hope for a better life, and who now understand that trade and investment tend to be keys to that better life. People in rich countries bemoan the horrible wages and living standards in these countries. And they are horrible. But the hard fact is that economic development is an arduous and extended process. If it pains you to think about these poor people, are you willing to donate, say, half your income and wealth to them? No? Then why deny them their legitimate shot at growthwhen in the process you'll benefit too?

What is most sad about the brew- ing U.S. public opposition to globalization is that it comes at a time of unparalleled economic prosperity. We are now enjoying the longest economic expansion in U.S. history, with rising real wages for all workers and nearly zero unemployment. Globalization and technology have been key driving forces of this boom. Despite all this, we cannot find the political will to resist those U.S. constituents opposed to globalization. With flush budget surpluses and a raging labor market, surely there is no better time to address these opponents: compensate workers for lost income or employment disruptions, retrain them, ignore them and let them find their own way in our economy, whatever. If the United States cannot marshal the political will now, what will happen when the economy cools?

What happened in Seattle does not bode well for anyone: neither the United States nor the rest of the world. By the time the WTO holds its next biannual ministerial conference in 2001, we will know whether bad will have turned to better or to worse.

Battle in Seattle Protesters fail torealize that trade and investmentare keys to a better life everywhere.

MATTHEW SLAUGHTER, an assistantprofessor of economics at Dartmouth, is a research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research and a visiting fellow at theInstitute for International Economics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

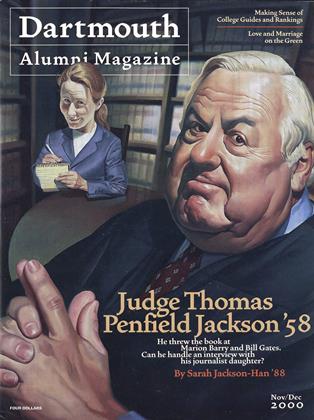

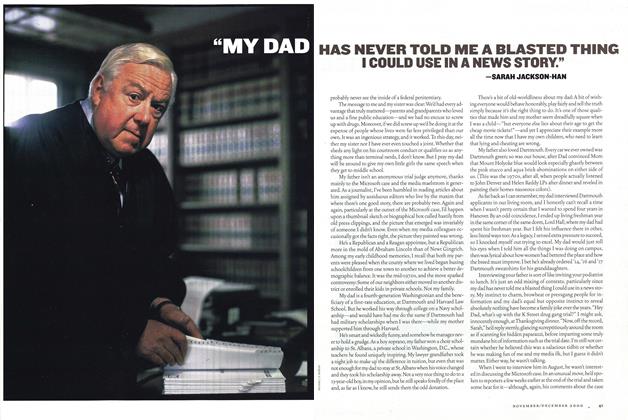

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000

Faculty Opinion

-

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

Nov/Dec 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONI Read, Therefore I Think

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2016 By DEVIN SINGH -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONHappiness and the Classics

Jan/Feb 2011 By Paul Christesen ’88 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionDouble Trouble?

May/June 2001 By Ronald M. Green