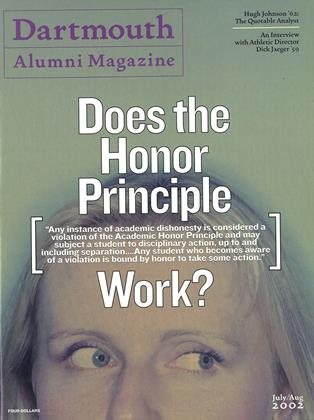

A Matter of Principle

A succeed-at-any-cost society has changed the nature of cheating. Is it time to reevaluate Dartmouth’s academic honor principle?

July/Aug 2002 Rick GreenA succeed-at-any-cost society has changed the nature of cheating. Is it time to reevaluate Dartmouth’s academic honor principle?

July/Aug 2002 Rick GreenA succeed-at-any-cost society has changed the nature of cheating. Is it time to reevaluate Dartmouth's academic honor principle?

They pore over computer date stamps and sift through reams of documents, trying to figure outwho wrote what and when. Sometimes they stare into the eyes of the remorseful—or the liars. They are the members of Dartmouth's Committee on Standards (COS), the College's overseers of undergraduate academic performance. When it comes to cheaters, the committee operates under a refreshingly simple guiding concept: "Any instance of academic dishonesty is considered a violation of the academic honor principle." But the issues of academic honesty the COS deals with can be thorny. Widespread and reckless use of the Internet, uneasiness about a new generation of students' research skills, and a blurred line between outright cheating and doing what it takes to get ahead are forcing the College to confront a difficult question: Does Dartmouth's 40-year-old honor principle work? II "We live in a really competitive society and the stakes do seem rather high," says Jon Sussman '02, a student member of the COS. "There are people out there who feel that the difference between [a grade of an] A and a B is the difference between being able to go to law school or not and the difference between success and failure." II Such a "grades are everything" perception may be why, in a formal survey of Dartmouth students last year, nearly half (48 percent) admitted to cheating in some form or another. All of the types of offenses mentioned were violations of the academic honor principle. So perhaps it's no surprise that the COS is "as busy as ever these days," according to Marcia Kelly, who heads the Undergraduate Judicial Affairs Office. Twenty-seven students went before the COS in the 2001-2002 academic year for alleged honor principle violations. In one case a student lied to a janitor to enter a building, slipped into a professor's office, found the answer sheet to the exam he had just taken and revised his answers. In another case, a student copied a friend's take-home exam. Another paraphrased an essay off a Web site that peddles term papers, while in another case a student made up a minor piece of data for a lab assignment. And in a more nuanced code violation, four students collaborating on a project shared answers when they were instructed to work only in pairs.

Among these cases, 13 students were eventually suspended. (The COS, which is made up of faculty, administrators and upperclassmen, can mete out punishments ranging from reprimands to "permanent separation" from the College. Its proceedings and the names of the accused are kept confidential, though it annually publishes the number and types of cases heard.) But more than anything else, it was the case of 63 students charged with cheating in a computer science class two years ago—dubbed "the CS4 incident" that tuned up the talk on campus about cheating, honor and ethics. All charges in that case were dismissed when the COS was unable to sort out who cheated and who didn't. But since the incident, a renewed sensitivity about cheating, and the apparent presence of more cheaters on campus, have made the honor principle subject to scrutiny.

"In light of the CS4 scandal, we did a lot of navel gazing," says Jane Carroll, Dartmouth's assistant dean of faculty. "In the past we always assumed [cheating] was one person by himself. Now it can be a whole class. If there is a whole group of students that doesn't perceive it as dishonesty, do we have to change the rules?"

Last fall 467 Dartmouth students participated in the survey of students about cheating and honor codes. (Complete results were not released to DAM; those reported in this story came from interviews and an "executive summary" of the survey provided by the Office of Public Affairs.) James Larimore, dean of the College, reports that while most respondents said they feel professors are supportive of the honor principle—and approximately two-thirds believe they themselves understand it—only one-third of the respondents said they were "likely" or "highly likely" to report a fellow student for academic dishonesty. Yet Dartmouth students are "bound by honor to take some action" if they see any kind of academic misconduct, a requirement that can be found on page 157 of the student handbook. What form this action should take is less clear. It can range from reporting the incident to a professor to the murkier "whatever the student feels is appropriate," according to the principle (the entire text can be found online at www.dartmouth.edu/~upperde/acad-regs.shtml).

Herein lies the principle's grayest element: the aspect of selfpolicing. The principle "leaves the individual with the responsibility to wrestle with the ethical question about 'what should I do?'" says Larimore, who also serves as a board member with the Center for Academic Integrity at Duke University, which is affiliated with the school's Kenan Institute for Ethics. "Promoting honesty and integrity is really what we need to do. Our job here at Dartmouth is to create the circumstances where people have to do some soul searching."

Whether enough of this soul searching is taking place is another question.

Recent statistics indicate cheating is on the rise at colleges and universities across the nation. But defining—and, more importantly, preventing—such misconduct is proving difficult.

Donald L. McCabe, a Rutgers University professor of organization management and founder of the Center for Academic Integrity, has surveyed thousands of students about cheating and honesty. (The Dartmouth survey was done in cooperation with McCabe.) His findings indicate that nationally, three-quarters of college students admit to at least some form of cheating, from inappropriate collaboration to wholesale plagiarism.

"You have this long-term trend suggesting that students are engaging in it more often. That is across the board," he says. "The Internet has really clouded the picture. Students are engaging in a lot of plagiarism and they don't even think they are doing anything wrong."

Yet, according to McCabe, there is significant cause for optimism. Honor codes, even old and crusty ones, can play a powerful role. His research indicates that rates of serious cheating are lower—by as much as 50 percent in some cases—at the fewer than 100 colleges and universities that have honor codes.

Some schools go to great lengths to bring academic honor front and center. Gazing out on 1,600 or so first-year students gathered in the Duke Chapel one day last fall, student Dave Chokshi, chair of the school's honor council, was anxious to make an impression. "You have the power to change things," he told those assembled for Duke's annual convocation.

For only the second year, Duke asked incoming freshmen to publicly sign an honor pledge last fall. Chokshi, a pre-med student, believes the pledge signing, however hokey, is changing some attitudes. "This is a way to make it more visible and make it more present in their minds," Chokshi says. "If you are coming to an institution like Duke you should expect to be coming into a climate where academic honesty is taken seriously."

"If you believe in it, then sign it," says Diane M. Waryold, executive director of the Center for Academic Integrity. "It is up to the institutions of higher learning to talk more about values," she says. Too often, she adds, students are only "rewarded for getting good grades, and if you don't get good grades you won't go to grad school. We should be teaching students to love learning."

Few schools take honor codes more seriously than the College of William and Mary in Virginia, where all forms of lying, cheating or stealing are grounds for permanent dismissal. The school's "honor pledge," which dates to Thomas Jefferson and is the oldest in the country, governs all student behavior.

"They hold their right hands up and they pledge to live by the honor code. It is a very influential moment in their college careers," says Danny Shaha, an assistant dean of students. This doesn't mean students don't have to be continually reminded about their responsibilities, though.

"We get a pretty high-level student, but just because a student is very intelligent and maybe affluent it doesn't mean they are mature. People get that confused," says Shaha. "They make mistakes, and they don't think about the consequences of their action."

Eighteenth-century values also don't always easily translate into 21st-century realities. Experts note that with the expansion of Internet-based research and e-mail communication on campuses during the last decade, decisions to cheat are made in seconds.

Last spring University of Virginia physics professor Louis Bloomfield learned just what this can mean. After a student in his popular "How Things Work" class told him that classmates were electronically sharing and trading previously submitted papers, Bloomfield devised a computer program that would look for similar passages among.the 1,500 term papers stored in his computer files. It wasn't the cheating that surprised him—Bloomfield quickly uncovered more than 100 papers with apparent plagia plagiarism—but the ease with which it was done.

Those who study the issue carefully don't believe the Internet is creating legions of new cheaters; it merely makes cheating easier. For example, Bloomfield s computer program also showed that most of his students weren't pilfering papers. Nevertheless, the Internet is creating havoc among a generation of students who may not understand enough about properly acknowledging and citing sources.

"In the old days, it was hard work. Now plagiarism has become much more easy," says Bloomfield. "What's gratifying is that the effort required to detect plagiarism has undergone the same transition."

As these examples attest, there are hints of a national awakening to the notion that standards of honesty can't be taken for granted. They must be continually reinforced and sometimes taught.

At Dartmouth, however, "Students are implicitly trusted to do the right thing," says Molly Stutzman '02, a COS member. "There is that assumption that students know where the boundaries are."

But they don't, according to Anne Cloudman '02. "My brother and mother and father—went to Rice, and they have an honor code that says it's a violation if you see cheating and don't do something about it," she says. "I didn't know that was part of the code here."

In an effort to fill the information gap, Kelly's Undergraduate Judicial Affairs Office has initiated discussion groups about the principle for first-year students during orientation and in dormitory gatherings. It is during those first weeks of a students college years when many assumptions and attitudes take hold. Its a time, students agree, when they could be better served by more emphasis on Dartmouth's expectations of academic honesty.

"It was a totally different approach compared to my high school," says Merrick Johnston '05, describing the leap from her home in Alaska to a classroom in Hanover. "Here in Spanish [my professor] just leaves the room when you have to take a test."

Kelly hopes to further promote discussion of academic honor by commemorating the 40th anniversaiy of the principle this summer (no details were available at press time). Despite these efforts, student turnout at the honor principle sessions has been low. Attendance is not mandatory.

Larimore says "it is possible" the College could sign up with one of the new online services designed to snare plagiarists. "These services can be helpful when plagiarism is suspected, but these services should only be used when plagiarism is suspected," says the dean. "I think it is better for us to say to our students, 'We trust you to do your own work. We have high expectations for you. Don't let us down,' rather than to say, 'We don't trust you and we're going to assume that you will try to cheat us and your classmates of your best efforts.'"

According to provost Barry Scherr and dean of faculty Jamshed Bharucha, a faculty committee has expressed support for subscribing to an online service that checks papers for plagiarism; uncertainty remains over who would administer the program and when it might begin. At least one faculty member, however, has already started using such a service. Goverment professor Allan Stam informed his students on the first day of class spring term that he'd be using a service called Turnitin.com, which students can also use. "If it all works out, no papers will come back indicating that anything has been written without attribution," Stam says.

As for establishing any formal rituals to promote the Dartmouth honor principle and what it stands for, Larimore says that he's open to the idea—but only if students say they want it.

"The central thing to me is that we have to give the honor principle back to the students," Larimore says. "It really has to be seen as a piece of community property rather than something that is imposed on them."

If history is any guide, Dartmouth students may prefer not to po- lice each other. On three occasions the student body has voted on the establishment of an honor system, and only once did it pass (see "A Short History of Academic Honor at Dartmouth" on page 39

In general, say administrators, the honor principle works and the COS responds effectively to cases brought before it. Larimore says even the mandate that students "take some action" works just fine and doesn't need tightening.

"It's a fair expectation that students can confront their peers," says Kelly. "They can tell or e-mail a student, 'I saw you looking at notes during the exam.' " If students don't wish to turn someone in, they can take other measures, according to Kelly. "They can talk to a faculty member or dean, and without naming names, can suggest that the professor take a second look at the exams. That's part of the trust between faculty and students," she says.

But the survey results of last year suggest students are not meeting these expectations. The results also indicate, according to Larimore, that a third of students feel the likelihood of getting caught cheating is low or very low—a worrisome sign on a campus where many decisions about cheating are left up to students.

Since the CS4 incident, the College has stepped up its instruction about the honor principle to new and visiting faculty. But the principle can be applied differently in different classes, depending on the professor and the work involved. That can further confuse students. According to Carroll, all faculty are expected to address the honor principle in class. But students report that doesn't always happen.

"The professors don't do a good job of promoting the honor principle. I don't think they stress it enough," says Dana Polanichka '02. "Dartmouth needs to make students more aware of not only the mechanics of the honor principle, but also the importance of the honor principle at the school specifically and in academia in general. Administrators, faculty and even students should be emphasizing academic integrity in every class, every term."

"I think we could do a better job of talking with first-year students about the honor principle," says Stutzman. "Not everyone reads the handbook and not everyone knows about the specifics."

Professor G. Christian Jernstedt says the question is hardly about students not grasping the meaning of an honor code. "What they are really naive about is what it feels like late one night when the pressure seems insurmountable. At that point their judgment is so clouded through stress that they make bad decisions," says Jernstedt, professor of psychological and brain sciences and a former member of the COS.

"In almost every case I saw reasonable people who too late recognized they got into this situation," he says. "They could have avoided it any number of ways. They lost their rationality. I don't think they understood what a severe penalty means in their life.

"I don't know any [professor] here who, if a student came in and said, 'I don't know how to cope,' wouldn't say, 'Let's see what we can do,' " Jernstedt says. "That's what office hours are for."

If Dartmouth is going to become a leader in the movement for greater academic integrity—instead of merely a top school with a decades-old honor principle—the way to begin is with those who teach and serve as academic role models for its students, says one longtime professor.

"Most faculty members don't want to waste time talking about this stuff," says Bernard Gert, chairman of the philosophy department. "I want to talk about it because it's ethics and philosophy. It doesn't resonate with a lot of the faculty."

Gert, on the faculty since 1959 and the Stone Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy, says cheating needs to be viewed less as a violation of some obtuse school law and more along the lines of "you are screwing your fellow student." Golfers, he notes, do a pretty good job .at policing each other because one cheater's score can affect everyone.

"Cheating used to be the lowest form of behavior," says Gert. "Call someone a cheat and that's a harsh thing. Why doesn't that translate into action in academic life?" a

A Short History of Academic Honor at Dartmouth

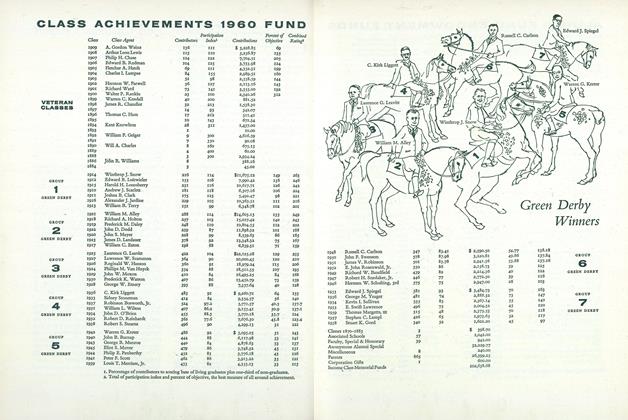

Honor PrincipleViolations, 1991-2001 The number of students brought before the COS for alleged violations (V), with number of suspensions (S) each year: Year V S 2000-01 27 13 1999-00 76* 7 1998-99 20 17 1997-98 2 0 1996-97 12 11 1995-96 14 8 1994-95 7 4 1993-94 14 12 1992-93 19 13 1991-92 33 "includes 63 students in the CS4 case

1895 The Dartmouth reports the occurrence of widespread cheating on exams, despite the presence of proctors. If caught, students are temporarily suspended.

1896 The faculty tries to curb cheating by passing a resolution calling for students who give or receive answers during exams to be permanently separated from the College. The new rule results in the expulsion of three students.

1897 Students draft a constitution for an honor system. It calls for students to end exams with a signed declaration that they "have neither given nor received aid in this examination." It repeals mandatory proctoring of exams and places the onus of the honor system on the students themselves. In addition to setting up a committee of 10 students to adjudicate violations, the constitution states, "Every student is expected to impress upon every other the full sense of personal honor." The faculty amends and approves the draft, then refers it to the student body for final acceptance. Despite initial enthusiasm, the students fail to vote the honor system into existence.

1951 Citing honor codes at Princeton, the University of Virginia and Wesleyan, the academic committee of Dartmouth's Undergraduate Council calls for an honor system. "An honor system would reduce the amount of cheating, first, by keeping the question of academic morality constantly before the students.... Secondly, we feel that cheating would be reduced by removing the sense of competition that is sometimes built up between students and proctors," the academic committee informs the Dartmouth community. When the proposed system comes up for a vote in 1952, students vote it down. Their main objection: They would be obligated to rat on other students.

1957 The chairman of the honor system committee of the Undergraduate Council encourages professors to informally use the honor system.

1961 A faculty resolution calls for an academic honor system "designed and enforced by the students of Dartmouth College."

1962 The Undergraduate Council drafts an honor principle, and the student body votes in favor of it. The principle discontinues proctoring and assigns responsibility for academic integrity to the students. "If necessary, students can invoke social sanctions to preserve this pact," states the principle, but it does not specify the sanctions or call for mandatory reporting of offenses. Adjudication of alleged violations is assigned to the Undergraduate Council. In February the faculty passes a resolution approving the honor principle and obligating professors "to provide continuing guidance as to what constitutes academic honesty."

1968 Students vote to abolish the Undergraduate Council. Responsibility for adjudicating alleged honor-principleviolations is transferred to the faculty-student College Committee on Standards and Conduct (CCSC).

1973 A survey of students by faculty and students finds that 63 percent of respondents admit to honor-principle violations. Of 263 students who say they know of violations by others, 69 percent say they have taken no action against the offender. A similar survey of faculty finds that only 33 percent of respondents mention the honor system to their classes each term.

1981 The Committee on Standards replaces the CCSC.

1983 The faculty adopts procedures for dealing with suspected violations of the honor principle.

1999 By the time the faculty adds feminine pronouns to it, the honor principle has been updated several times. Additions include outlawing unauthorized collaborations and use of the same work in more than one course.

Karen Endicott

"I wouldn't turn someone in because I know there are huge repercussions,andi wouldn't want to do that to someone. The honor code is more for myself." RAJIB CHOWDHURY '02

"It's very complex. If someone copied something for a thesis I would probably turn them in. If someone asked me a question that was on a take-home [exam] I probably wouldn't." ALEX NAZARYAN '02

"I didn't know that I had to take action when others cheat." JING WANG '02

"If I saw someone who was definitely, absolutely cheating, I would probably tell someone. I think it's disrespectful." CHRIS LALLY '03

"Cheaters are Wasting their education. I'm not going to make their problem mine." LONNIE THREATTE '02

"My interpretation of the honor system places responsibility in the hands of the person who might be doing something wrong, not other students." LYDIA SMITH '04

In a recent survey of students, 48 percent respondents admitted they d violated the cademic honor principle in some way.

RICK GREEN is a staff writer at The Hartford Courant He has won numerou national awards for his coverage of education issues during the last10 years. Roxanne Khamsi '02 provided additional reporting for this story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

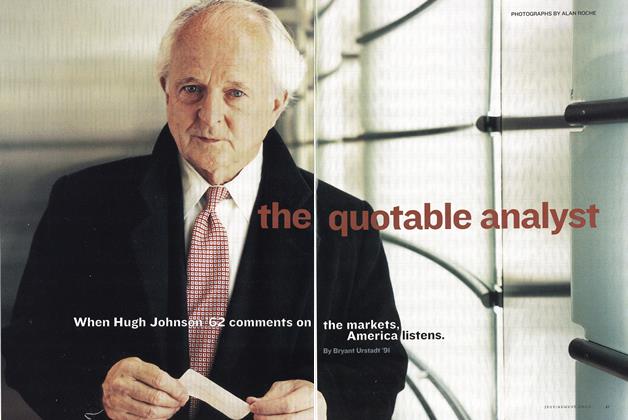

FeatureThe Quotable Analyst

July | August 2002 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July | August 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49 -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July | August 2002 By Jay Heinrichs -

Interview

Interview“We’ve Got To Go For It”

July | August 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMHeaven and Hell in the Middle East

July | August 2002 By Alex Hanson -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

July | August 2002