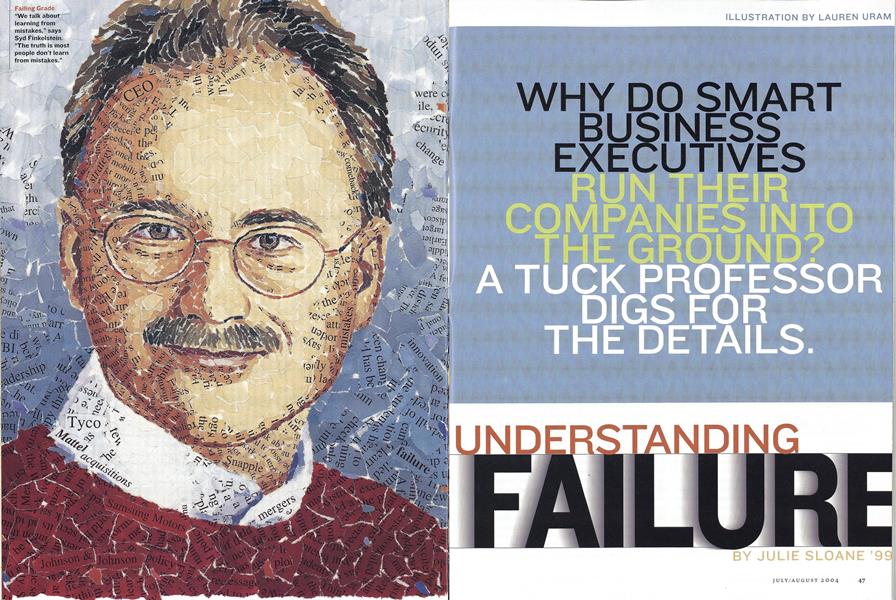

Understanding Failure

Why do smart business executives run their companies into the ground? A Tuck professor digs for the details.

Jul/Aug 2004 JULIE SLOANE ’99Why do smart business executives run their companies into the ground? A Tuck professor digs for the details.

Jul/Aug 2004 JULIE SLOANE ’99WHY DO SMART BUSINESS EXECUTIVES RUN THEIR COMPANIES INTO THE GROUND? A TUCK PROFESSOR DIGS FOR THE DETAILS.

IF THERE'S ONE GENERALIZATION TO BE MADE ABOUT business books, it would be this: They're light reading. To say it another way, most of them stink. Big time. Business authors seem enchanted by needless metaphors to repackage dimestore wisdom such as "strike while the iron is hot" or "what goes up must come down." Scan the covers of any 50 business books in Barnes & Noble and you'll find an awful lot of self-styled experts with hazy credentials avowing that everything you need to know about business can be learned by watching your pets or studying a fill-in-theblank historical figure.

In this cynics playground, Tuck professor Sydney Finkelstein has managed an impressive feat, bringing academic rigor to a common but surprisingly unexplored issue: failure. His latest book, Why SmartExecutives Fail, runs counter to the business canon's near universal focus on success and best practices. "The problem with these types of books," says Finkelstein, "is they look at 20 companies and say, 'The following attributes were the cause of their success, therefore you should do the same type of thing.' But they never look at the hundreds, if not thousands, of companies that have exactly the same attributes but fail." There are entire libraries of self-help books on personal failure, books on military failure and case studies with titles like The Riseand Fall ofX. Never before, says Finkelstein, has anyone written a comprehensive analysis of corporate failure. Yet in many ways it's a subject hiding in plain sight. "We always talk about learning from mistakes," says Finkelstein. "It's just common language. But the truth is most people don't learn from mistakes." That's why failure lurks even among the blue chips; Rubbermaid, Johnson & Johnson and Sony all found their way into Finkelstein's book.

Fail Finkelstein hasn't, with the paperback out in June. He has already raked in praise from The Wall Street Journal and The Economist, and for a time hit No. 16 in sales atAmazon.com. ("That's up there with Hillary Clinton and Seabiscuitl" laughs the 45-year-old.)

Finkelstein is quick to debunk the most common assumptions about why companies fail. With the recent spate of corporate scandals and subsequent public flogging of Enron, World Com and Adelphia executives, the corruption theory has gained momentum. But Finkelstein feels that while crooked executives may explain Enron's failure, on the whole, most executives of failed companies were operating within the law. It is also tempting to conclude that failure happens when executives are incompetent, stupid even. In fact, Finkelstein argues, CEOs of large corporations are among the more brilliant people around. "Not just anyone gets to run a billion dollar company," he says. "A lot of people pick them over a lot of others." These executives almost always have incredible track records. Mattel's Jill Barad built Barbies sales from $250 million to $2 billion before a bad acquisition and streak of missed earnings earned her a successor. Brothers Maurice and Charles Saatchi built the largest advertising agency in the world in Saatchi & Saatchi, with 18,000 employees and $7.5 billion in billings, until a voracious and illogical appetite for acquisition sent the stock down 98 percent in value and the Saatchis packing.

Companies themselves often explain their failure with what Finkelstein calls "the perfect storm" fallacy. Just as three storms unpredictably converged in the North Atlantic in Sebastian Junger's book of the same name, businesses tend to explain failure by saying customers suddenly wanted A and not B, then the dollar weakened and suddenly a new technology hit the scene and whoops! Who could have known?

More often than not, argues Finkelstein, they did know. They simply chose denial over action, and this is one of the seminal lessons of the book. 'Academic research on strategy talks a lot about how major changes to an industry wipe out companies," says Finkelstein. "So I expected that to be the explanation for a bunch of these failures. It was a big surprise forme that so many of these people knew what was going on, could see that the industry was changing, had the data and yet did nothing."

His favorite example is Motorola's failure with Iridium, a satellite-based mobile phone system conceived in the late 1980s to allow global use of cell phones. It seemed like a good idea when Motorola spun off Iridium in 1991, less so in late 1998, when the service launched to the public. Iridium phones were literally the size of a brick, expensive ($3,000 for a handset and up to $8 per minute to call) and didn't work indoors. Motorola sank $5 billion into the project, the majority of it after 1996. By then it was apparent the target market, international business travelers, was increasingly served by a proliferation of cheaper handsets. Rather than heed the data and cut its losses, Motorola pursued what it believed to be the perfect product all the way to a Chapter 11 filing in 1999.

The examples cross industry lines. In the late 1940s the Boston Red Sox were one of the dominant teams in baseball, yet through the 1950s their performance deteriorated. Why? In large part, Finkelstein says, it was racism. Boston was the last team to add black players to its roster, which it did in 1959,12 years after the Brooklyn Dodgers brought on Jackie Robinson. By comparing the number of black players on a team with win-loss records, Finkelstein found a direct correlation between integration and team success. "Organizations that adopted a segregationist strategy were following an irrational strategy," he writes. If the goal of team management is to win games, their decision to continue excluding great players based on race was, Finkelstein writes, "arguably the single worst decision in the history of the team."

Mild-mannered, sincere and seemingly always at ease, Finkelstein—who happens to root for the Montreal Expos—is almost impossible to dislike. If you were a CEO facing a mob of disgruntled shareholders, you'd want Finkelstein to do the talking. He's a favorite at Tuck executive conferences, and he teaches classes on mergers and acquisitions, top management teams, and a first-year course called "Analysis for General Managers." The latter has incorporated many of Finkelstein's findings on failure.

Finkelstein, who's been at Tuck since 1993, speaks rapidly but halts slightly between sentences with a pragmatic pause and full eye contact, as if to say, "This all makes great sense, doesn't it?" In fact, it does, and not by accident. Why Smart Executives Fail is the product of six years spent personally interviewing 197 CEOs, former CEOs and senior executives with firsthand knowledge of the 50 companies he studied. He spent more than four years piecing together his theories before writing a single word of the book. Some of it was written over coffee at the Dirt Cowboy Cafe on Main Street, where he also had his Hanover book signing and can still be found most mornings when he's in town.

It was at Dirt Cowboy, over the whoosh of milk foamers, that Finkelstein described how he was able to get the men and women behind such public failures to go on record with their stories. "Well, I didn't have any confidence that they would," he admits, but to his initial puzzlement, many wanted to talk, to unburden themselves of their guilt or unease. "They just felt like they had to come clean, and this was a relatively safe place to do that. They probably assumed a professor from a prestigious school would be more fair than the business press." Many were still angry. One CEO, a successful multi-millionaire in his 70s, was furious about his successor's failure, calling the man "a big baby" and accusing him of building the biggest house in town and hiding his face inside it. "It was schoolyard stuff," says Finkelstein in wonder. Others were in denial. When Finkelstein asked another CEO about the hundreds of millions of dollars lost under his tenure, those were the last words the professor got in for the rest of the interview. Says Finkelstein, "He spoke nonstop for 30 minutes in a highly analytical fashion; went through a list of seven people or groups who were to blame: 'lt was government regulators. It was my CFO. It was our customers.'"

There is a lot to be learned in such rationalization, insists Finkelstein. Sill Smithburg was the CEO of Quaker in 1994, when the company bought Snapple for $1.7 billion and sold it for $350 million two and a half years later. Yes, Smithburg conceded, mistakes had been made, but rather than delve into those, he preferred to talk about his greater success, Gatorade, which, prior to the purchase of Snapple, he'd built into a $2 billion-plus brand. "He believed Snapple was going to be the next Gatorade and became entranced by the opportunity to do it again," says Finkelstein. "It looked like a chance to relive the greatest moment of his career." But reality quickly set in—these two brightly hued beverages were not the same. Snapple had long-term contracts with small, family-run distributors who were unwilling to adopt the same systems Quaker used for Gatorade, effectively thwarting Quakers plans. And yet it was a fact Quaker knew or should have known from the beginning.

All this facing the music seems a tad brutal. If a company fails, is the CEO always to blame? Not always. Most people consider it a failure that in the 1980s IBM outsourced to Microsoft and Intel what turned out to be the two most lucrative parts of a PC—the operating system and processing chips—essentially forfeiting billions in revenue. But after studying IBM, Finkelstein disagrees. "What IBM essentially did was outsource those areas of its business that were not critical to its success at that time," he explains. "Knowing what people knew then, would reasonable people have done the same thing? The answer for IBM is yes, the answers for companies in the book is no. A resounding no."

Since Finkelstein spent six years studying and writing about failure and the past year crisscrossing the United States, Australia, Japan and England lecturing about the book, you might surmise that he is setting himself up as the father of failure. What's his next project? "The one thing I know I'm not doing next is another book on failure," he says immediately. Despite a rash of high-profile scandals and failures such as Freddie Mac, Health South and the New York Stock Exchange since the books debut a year ago, Finkelstein feels that everything he learned about the root causes of corporate failure is already in this book. "What I've become most interested in is people," he says. "Even though this book is all about big business, the bottom line is that failure rests on people." He's currently mulling a future book about how chefs, writers and other creative types turn their talents into profits. As he moves from bankruptcies to beef Wellington, Finkelstein hopes his study of failure will actually help executives succeed. When he wrote the book in 2002, he ended it on a hopeful note: "Maybe the Red Sox will win it all next year." They almost did. Maybe now they'll pick up the paperback.

Failing Grade "We talk aboutlearning frommistakes," saysSyd Finkelstein."The truth is mostpeople don't learnfrom mistakes."

"IT WAS A BIG SURPRISE FOR ME THAT SO MANY [CEOs] KNEW WHAT WAS GOING ON, HAD THE DATA AND YET DID NOTHING."

JULIE SLOANE is a writer at Fortune Small Business magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

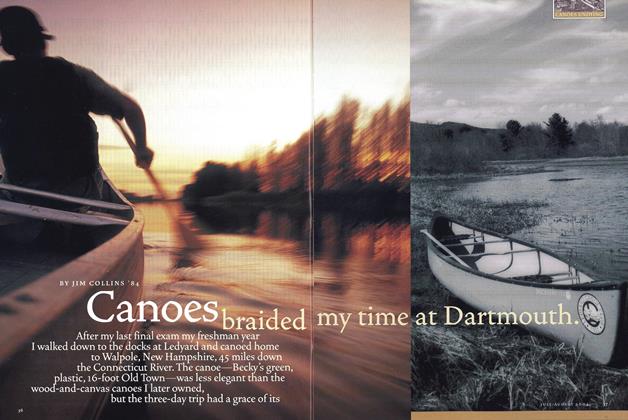

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

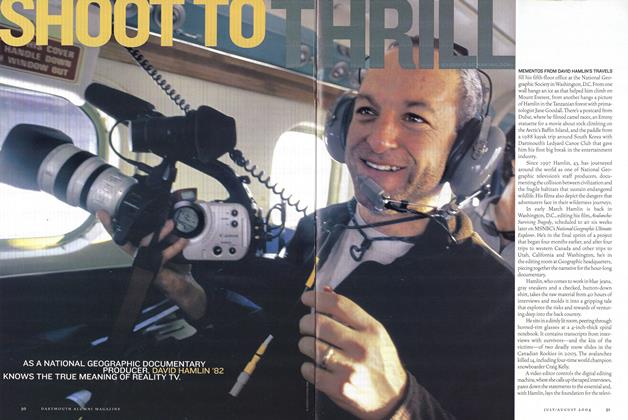

Feature

FeatureShoot to Thrill

July | August 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

July | August 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

Sports

SportsYouth at Risk

July | August 2004 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionMoney Matters

July | August 2004 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

JULIE SLOANE ’99

-

Article

ArticleHealing Outside the Hospital

MAY 2000 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNew Dimensions

Nov/Dec 2005 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Cutting Edge

May/June 2011 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOh Behave!

July/August 2012 By Julie Sloane ’99

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

FeatureWorlds Together

SEPT. 1977 -

Feature

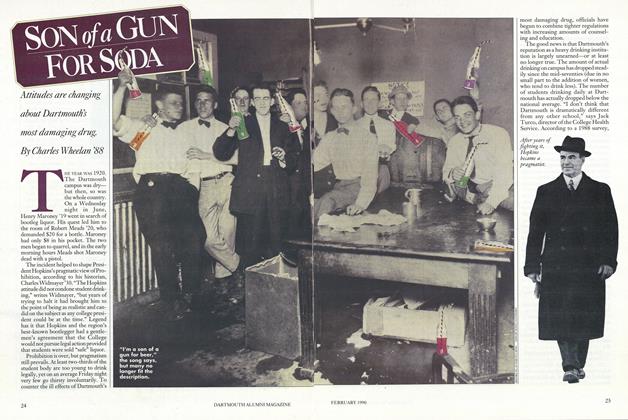

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Feature

FeatureCan Education Kill the Movies?

JANUARY 1968 By Maurice Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

DECEMBER 1965 By R.B.