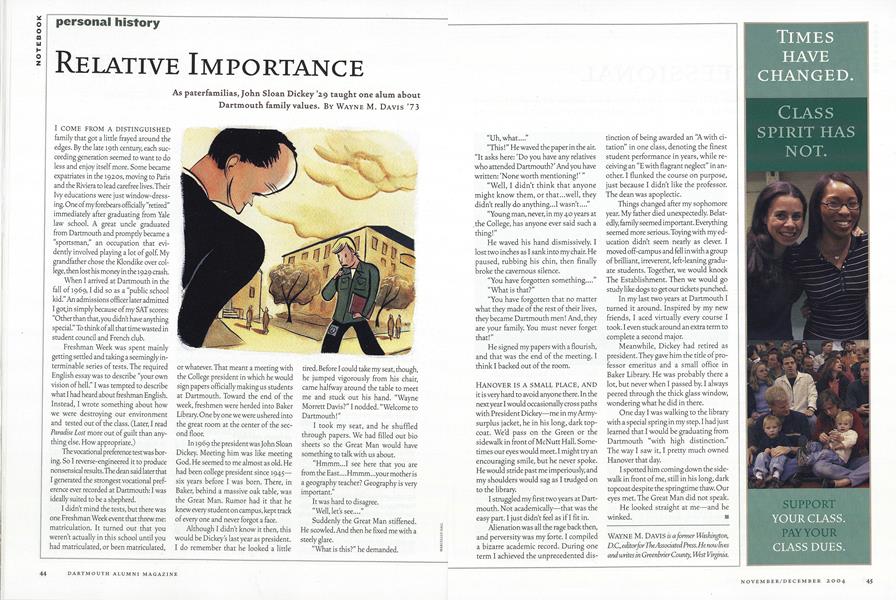

Relative Importance

As paterfamilias, John Sloan Dickey ’29 taught one alum about Dartmouth family values.

Nov/Dec 2004 Wayne M. David ’73As paterfamilias, John Sloan Dickey ’29 taught one alum about Dartmouth family values.

Nov/Dec 2004 Wayne M. David ’73As paterfamilias, John Sloan Dickey '29 taught one alum about Dartmouth family values.

I COME FROM A DISTINGUISHED family that got a little frayed around the edges. By the late 19 th century, each succeeding generation seemed to want to do less and enjoy itself more. Some became expatriates in the 19205, moving to Paris and the Riviera to lead carefree lives. Their Ivy educations were just window-dressing. One of my forebears officially "retired" immediately after graduating from Yale law school. A great uncle graduated from Dartmouth and promptly became a "sportsman," an occupation that evidently involved playing a lot of golf. My grandfather chose the Klondike over college, then lost his money in the 1929 crash.

When I arrived at Dartmouth in the fall of 1969,1 did so as a "public school kid." An admissions officer later admitted I gotin simply because of my SAT scores: "Other than that, you didn't have anything special." To think of all that time wasted in student council and French club.

Freshman Week was spent mainly getting settled and taking a seemingly interminable series of tests. The required English essay was to describe "your own vision of hell." I was tempted to describe what I had heard about freshman English. Instead, I wrote something about how we were destroying our environment and tested out of the class. (Later, I read Paradise Lost more out of guilt than anything else. How appropriate.)

The vocational preference test was boring. So I reverse-engineered it to produce nonsensical results. The dean said later that I generated the strongest vocational preference ever recorded at Dartmouth: I was ideally suited to be a shepherd.

I didn't mind the tests, but there was one Freshman Week event that threw me: matriculation. It turned out that you weren't actually in this school until you had matriculated, or been matriculated, or whatever. That meant a meeting with the College president in which he would sign papers officially making us students at Dartmouth. Toward the end of the week, freshmen were herded into Baker Libraiy. One by one we were ushered into the great room at the center of the second floor.

In 1969 the president was John Sloan Dickey. Meeting him was like meeting God. He seemed to me almost as old. He had been college president since 1945— six years before I was born. There, in Baker, behind a massive oak table, was the Great Man. Rumor had it that he knew every student on campus, kept track of every one and never forgot a face.

Although I didn't know it then, this would be Dickey's last year as president. I do remember that he looked a little tired. Before I could take my seat, though, he jumped vigorously from his chair, came halfway around the table to meet me and stuck out his hand. "Wayne Morrett Davis?" I nodded. "Welcome to Dartmouth!"

I took my seat, and he shuffled through papers. We had filled out bio sheets so the Great Man would have something to talk with us about.

"Hmmm...I see here that you are from the East....Hmmm...your mother is a geography teacher? Geography is very important."

It was hard to disagree.

"Well, lets 5ee...."

Suddenly the Great Man stiffened. He scowled. And then he fixed me with a steely glare.

"What is this?" he demanded.

"Uh, what...."

"This!" He waved the paper in the air. "It asks here: 'Do you have any relatives who attended Dartmouth?' And you have written: 'None worth mentioning!' " "Well, I didn't think that anyone might know them, or that...well, they didn't really do anything...l wasn't...." "Young man, never, in my 40 years at the College, has anyone ever said such a thing!"

He waved his hand dismissively. I lost two inches as I sank into my chair. He paused, rubbing his chin, then finally broke the cavernous silence.

"You have forgotten something...."

"What is that?"

"You have forgotten that no matter what they made of the rest of their lives, they became Dartmouth men! And, they are your family. You must never forget that!"

He signed my papers with a flourish, and that was the end of the meeting. I think I backed out of the room.

HANOVER IS A SMALL PLACE, AND it is very hard to avoid anyone there. In the next year I would occasionally cross paths with President Dickey—me in my Army- surplus jacket, he in his long, dark topcoat. Wed pass on the Green or the sidewalk in front of McNutt Hall. Sometimes our eyes would meet. I might try an encouraging smile, but he never spoke. He would stride past me imperiously, and my shoulders would sag as I trudged on to the library.

I struggled my first two years at Dartmouth. Not academically—that was the easy part. I just didn't feel as if I fit in. Alienation was all the rage back then, and perversity was my forte. I compiled a bizarre academic record. During one term I achieved the unprecedented distinction of being awarded an "A with citation" in one class, denoting the finest student performance in years, while receiving an "E with flagrant neglect" in another. I flunked the course on purpose, just because I didn't like the professor. The dean was apoplectic.

Things changed after my sophomore year. My father died unexpectedly. Belatedly, family seemed important. Everything seemed more serious. Toying with my education didn't seem nearly as clever. I moved off-campus and fell in with a group of brilliant, irreverent, left-leaning graduate students. Together, we would knock The Establishment. Then we would go study like dogs to get our tickets punched.

In my last two years at Dartmouth I turned it around. Inspired by my new friends, I aced virtually every course I took. I even stuck around an extra term to complete a second major.

Meanwhile, Dickey had retired as president. They gave him the title of professor emeritus and a small office in Baker Library. He was probably there a lot, but never when I passed by. I always peered through the thick glass window, wondering what he did in there.

One day I was walking to the library with a special spring in my step. I had just learned that I would be graduating from Dartmouth "with high distinction." The way I saw it, I pretty much owned Hanover that day.

I spotted him coming down the sidewalk in front of me, still in his long, dark topcoat despite the springtime thaw. Our eyes met. The Great Man did not speak.

He looked straight at me—and he winked.

WAYNE M. DAVIS is a former Washington,D.C., editor for The Associated Press. He now livesand writes in Greenbrier County, West Virginia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

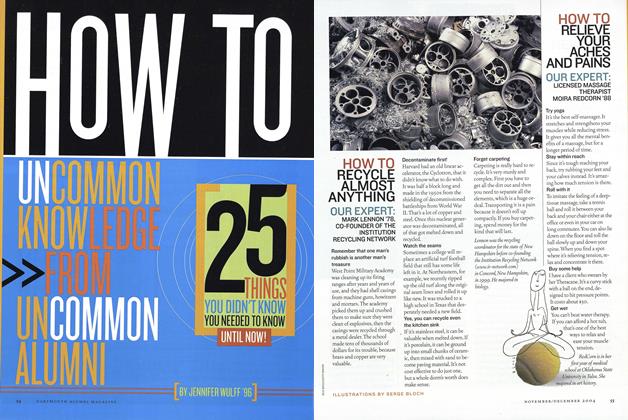

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

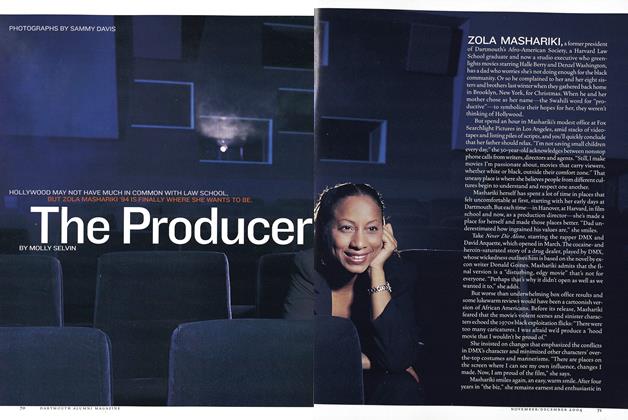

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Sports

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83

Personal History

-

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Serpent’s Call

Jan/Feb 2003 By BREEANNE CLOWDUS ’97 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Devil and Dan Club

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jim Collings ’84 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

Sept/Oct 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOver the Hill?

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By MIKE STANITSKI ’92 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYChasing Pollock

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By SAM SEYMOUR '79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPride and Progress

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By VAL WERNER '21