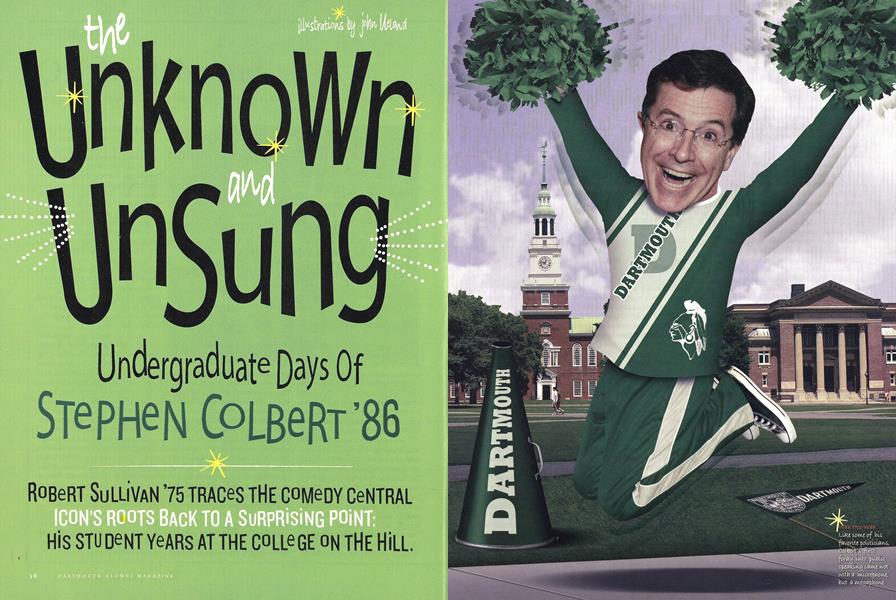

The Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

Robert Sullivan ’75 traces the Comedy Central icon’s roots back to a surprising point: his student years at the College on the hill

July/August 2008 Robert Sullivan ’75The Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86 Robert Sullivan ’75 July/August 2008

Robert Sullivan ’75 traces the Comedy Central icon’s roots back to a surprising point: his student years at the College on the hill

July/August 2008 Robert Sullivan ’75Undergraduate Days Of Stephen Colbert '86

RoBeRT SULUVAN '75 TRACeS THE COMeDY CeNTRAL His STUDENT YeARS AT THE ON THE HILL.

"Oh Yeah',(I said to myself). I had forgotten. I had just been told by my wife that she saw an interview with Stephen Colbert '86 in Ana Marie Cox's blog. "Did you know," my wife asked, "that Colbert went to your college?"

"Yes," Luci said. "Colbert mentioned on the blog that he thinks he slept with Ingraham back when—he couldn't quite remember. I thought that was unfortunate. I don't like to think of Stephen in that way, having sexual relations out of wedlock. He said he felt he'd been offered a good education but had basically wasted it."

"I forgot he was Dartmouth," I said. "He wasn't as famous as the others back then, so I'd forgotten. Of course, it makes total sense when you think about it."

My wife and I are huge fans of Stephen's always incisive television program, The Colbert Report, and share many of his core passions—for God and Jesus, for America, for our current president, for ultraconservative politics, for truthiness in the affairs of men. It is perhaps too much to say that he is a hero to us, but it is absolutely fair to say that we admire him greatly and that, generally, he speaks for us. As he does for so many other patriots in this great republic of ours. Given the candidates we have been delivered by the electorate, it is an obvious shame that the two major parties conspired early in the presidential race, by pointing to obscure, archaic and seldom-exercised rules, to keep Colbert off the primary ballot in his native South Carolina, thereby derailing his audacious bid for the White House even before it could leave the station.

"I wonder what it was like for him up there?" I mused aloud. "I wonder how he liked Dartmouth? A lot of us feel like we squandered an education—that's nothing new—but I wonder if he had fun?"

"You're in the business," said Luci. "Why don't you find out?" "Good idea," I said.

And so I set out to do this piece on Colbert's Dartmouth years. First stop, of course: the man himself.

Curiously, Colbert was unwilling to talk further on the subject. His office politely told me that he wasn't going to be revisiting the Dartmouth topic anytime soon.

Why not? I wondered.

This wasn't off to a very good start. Where to next?

I was in Dartmouth's class of 1975, so I and my friends were a decade removed from Colbert. My sister, Gail, was much closer, a Dartmouth '82. So I called her up and asked her what she knew.

"Well, Sull,"—we call each other Sull—"he was a huge topic of conversation at our 25th reunion last spring. He's gotten so big, everyone was telling stories—what they remembered, what they'd heard."

"Did he sleep with Laura Ingraham?"

"No way, was the consensus. He was always mooning over her at the field hockey games, apparently. That's the only sport he ever went to—women's field hockey. He stalked the practices, they say, just gazing at Laura. And during games he made a spectacle of himself. He brought a megaphone, and had a bunch of Lauraspecific cheers. That must have been quite a sight.

"The whole story about his time on campus," she continued, "seemed a little sad. Even pathetic. He was kind of a wanna-be: wanna be the new Dinesh D'Souza, wanna be with Laura, wanna be like Laura—wanna out some gays myself in the Review, wanna grab the spotlight myself—-wanna be this or that character, a character that was always bigger than himself."

I found this disheartening. "But he's such a substantial man now," I said. "He's so authentically himself."

"I know, it's weird," said Gail. "He was different at Dartmouth, but, you know, we were all younger. We were trying to become who we were going to be.

"They say he was always asserting himself, then drawing back," she continued. "I remember after I'd graduated I was back visiting during Carnival the year that the prof sued Ingraham for something she'd written in the Review. Remember that? And I heard at the time that there was this guy who was going to go beat up the prof for her—beat him up, or worse. Everyone was worried about it, this big, tense topic: some anonymous terrorist on campus. So at the reunion last year, when we're telling these stories, it comes up that the guy was Colbert. And you know what he did, after getting the whole campus on edge about this avenging angel ready to attack a professor? Nothing. It was all bluster—trying to impress Laura."

"Did you know her?" I asked. (Ingraham was class of 1985.)

"I saw her. All the time. Her and D'Souza" (who was class of 1983)."They were more than pals, they were a pair. Always laughing as they walked across the Green. I believe at one point, later, they were engaged."

"Yes, I did know that," I said. "So what was the deal with Colbert and the two of them?"

"He was the tag-along puppy."

This seemed so sad to me. This man who was such a lion, such a...

...such a monument...

...had once been a....

STEPHEN TYRONE COLBERT WAS BORN ON MAY 13, 1964, the youngest of 11 children. His heritage is Irish (his claim that his surname is French represents, he has admitted, a ruse to trick liberals into appearing on his show). He was raised in Charleston, South Carolina, in a devoutly Roman Catholic family. Although Colbert remains a practicing Catholic today, early in life he developed an almost unholy fascination with fantasy and mythology. He devoured Tolkien and became so desperately addicted to the video game Dungeons & Dragons that his parents sent him to an exorcism day-camp. The counseling there didn't take, and he is remembered as an all-afternoon D&D player during his Hanover years. Those years began in 1982 after Colbert chose Dartmouth over Hampden-Sydney College, Bob Jones University and Northwestern, to which he was also accepted. It's wholly unsurprising that Colbert was able to score yeses from not one but four of the nations very finest institutions of higher learning when you consider the persuasive—and ingenious—application essay he sent to Dartmouth, which he reprinted last year in his eloquent and characteristically candid memoir lAm America {And So Can You!): "'America is therefore the land of the future, where in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the Worlds history shall reveal itself,' said the philosopher, scholar and lover-of-thought George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

"In conclusion, my great-great-uncle was Daniel B. Fayerweather of Fayerweather Hall."

Colbert generously reveals in his book the secrets behind the essays brilliance. "Secret number one: A thesaurus. Eggheads love the words, so the more you jam in there, the better. Think if it as a verb sausage." And, "Secret number two: The last sentence. All it takes is a little research and you can find the campus library, dormitory or stadium that most plausibly could have been donated by your family. You'd be surprised how rarely these folks check into your background if you show up to the interview wearing an ascot."

Would that I had been counseled so cleverly back in 1971! And to think Mom wasted her money on that I green bowtie for the interview. [Note: The Dartmouth admissions office was unavailable for comment on Colberts long-ago subterfuge or on the allegation that it might be in any way lax in its fact-checking.]

So Colbert gains admission. Now, from what I've been able to learn, the freshman arrived at Dartmouth wideeyed and expectant, but quickly hit a bump. His freshman trip did not go well. In a talk at Harvard in 2006 Colbert said that his outsized fear of bears—he has called them "godless killing machines" and has frequendy pointed to them as a grave threat to the republic—is the byproduct of a recurring dream in which a large bear is standing between him and his goal (an unspecified but important goal, perhaps something akin to the canonization of Father Coughlin or the demise of the Democrat Party). But, according to those who were there at the time, Colberts arctophobia is directly traceable to an incident that occurred in the lower reaches of Mount Moosilauke.

"By the time his trip got to the Ravine Lodge," Jim Collins '84 told me, "all the others in his group were sick of him." "Noway."

"Definitely," said Collins, who lives in Orange, New Hampshire, not far from the campus. "I was leading another trip that year and we had already reached the Lodge. His group comes in—they'd been hiking in the Franconia Range—and he starts complaining about everything. The food. The bugs. When we told ghost stories at night he put his pillow over his ears. I asked the other kids in his trip if he'd been like that right along, and they said absolutely. When they went skinny dipping in Echo Lake he was appalled. Some of the others on the trip were smoking marijuana and Steve was horrified—and said so. 'Why do you think they call it dope?' he asked, and apparently acted as if he'd thought that up himself. At one point his Siouxsie and the Banshees tape disappeared—he had been playing it on a Walkman all the time while he hiked, and humming along—and he claimed it had been stolen. Maybe it had. I wouldn't be surprised on that one.

"So they get to the Ravine Lodge, and of course he won't eat the green eggs and ham—he's claiming Dr. Seuss is a 'pinko' for his enviro views in Lorax and his Joe McCarthy-bashing in Horton. Steve's having just an awful time, he's truly miserable, and things only get worse. Next day there's the summit hike, and his new 'pals' just take off. They ditch him, and there's no way Steve can keep up. Then he gets all excited—just like he does sometimes on TV—and disoriented. He loses the trail. That's when he saw the bear—a small one, I'm sure, if there was a bear at all. No one else saw it. Might have been a dog. A raccoon. Might have been his shadow.

"The good news was he was only about 200 yards up the hill at this point, so by running straight downward he popped out of the woods near the volleyball court. He was screaming, 'Killer bear! Killer bear!' and—well, I hate to tell you this, because you said how much you admire him, but...well, everyone who was playing or reading or having a beer stopped what they were doing, wondered what the heck was going on and then...well, they laughed at him."

"Goodness," I said. "How did he react?"

"Not well. He was clearly humiliated. Furious. Here he was being dead serious and everyone thought he was being funny."

"Imagine."

COLBERT JOINED THE NASCENT REVIEW IN HIS FIRST semester. "He was Dinesh's coffee-fetcher, is the way I hear it," my sister Gail said. "Theßeview had what amounted to its own system of hazing. But Stephen, with that monumental strength of character of his, persevered."

Though he didn't necessarily prevail. His Review career is, rather astoriishingly, not of the luster of those of his comrades in arms. While D'Souza and Ingraham were getting noticed not just in Parkhurst Hall but in the salons of Boston and New York and Washington, D.C., Colbert was writing the occasional newsbreak—"How many psych majors does it take to..."— and trying to get his cumulative average up. He was, as he admirably conceded in the Cox blog, not a scholar. In point of fact, he struggled. He was a history major, and except for a B-plus in James Wrights "Cowboys and Indians"—which in that era was considered a borderline gut—the walls of the Ivory Tower represented, for Colbert, a gulag. It is scant surprise that he now says, as he does in his memoir, "If there's a bigger contributor to left-wing elitist brainwashing than colleges and universities, I'd like to see it. There's an old saying, A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.' Which means a lot of knowledge must be a really dangerous thing. And it is." Some might take these remarks as the resentment of a man ill-treated by the academy, but I take them as something more: a remarkably perspicacious observation.

The term paper that earned Colbert a good mark in Wrights course was a cogently and vigorously argued defense of Manifest Destiny, and he did well enough in professor Jeffrey Hart's classes too, equaling his "Cowboys and Indians" performance in Harts "The Augustan Age." But he did poorly in the sciences and even social sciences (stunning, that) and quite nearly flunked French.

Why Colbert took French in the first place is curious, to say the least; perhaps he was traveling undercover with a plan to out French majors. I wondered what hostility—either to the subject matter or between individuals or both—could possibly have caused such a bright young man to pull a D-minus in any course.

I called professor John Rassias and asked if he recalled Colbert.

"Ah, mais oui. Certainment," he answered. "That was an unfortunate case. Triste. Triste. And it was perhaps—peut-etre—my own failing as much as—more than! mon dieu! more than!—his. He resisted the language from the first day, and resisted all else. He seemed resentful of the fun in class, the joie de vivre, the comedy. I tried to pull him in, and that was a tragic—a grave—mistake. One day I played affectionate games with his name—Col-BERT he called himself back then, and I suggested Col-BEAR as sounding so much more sophisticated, cultured, dashing. He fumed, though I see by what I read about him now, at some point he came round.

"The worst day was, well, I hesitate to even recall it. Do you remember the game I used to play with the egg, breaking I'oeuf, I would break it over a students head? It was great sport, n'est-ce pas? Well, one day—again, trying to draw him in—l did this with pauvre Stephen. And he, I would say, freaked out. There's no equivalent phrase in French—he simply freaked out. He ran from the class screaming. He was cursing me, cursing the French—he was urging upon me, and all things French, utter and eternal damnation.

"He got the D-minus out of sympathy, and my own guilt." Goodness, I thought to myself. Colbert's Dartmouth was just one what-fresh-hell-is-this? after another.

HE WAS A FRAT BOY, MORE OR LESS. A MEMBER OF TABARD, he was said to be a poor to fair—but wildly enthusiastic—beer pong player, and there are indications he still plays today. Sam Means '03, an Emmy-winning writer on Jon Stewart's Daily Show, which Colbert elevated on a nightly basis before being awarded his own half-hour, told me, "I never actually got to work with Stephen, but I heard he once tried to put a pong table in the crew lounge." Whether this gracious attempt at camaraderie and bonding was successful—or even occurred—Means couldn't say, but he did note that Stephen was generally well-liked by the staff and was considered a team player.

I thought about how those aspirations—to be liked, to be part of the gang—had surely been part of Colbert s makeup during his Dartmouth years, only to be frustrated time and again. When not in his dorm, at The Review or in Tabards basement he was often alone. Rob Kutner, a colleague writer of Means' on the Stewart program, recalled that when Colbert reminisced about the College, which was rarely, "He often spoke of just hanging out in some place called the Bema. And I thought that was weird, because he wasn't even Jewish."

Colbert presumably did find a measure of fellowship in the men's singing society The Sing Dynasty, which was composed of brethren from Tabard and Tri-Kap who had, for one reason or another (vocal in some cases, certainly political in others), been excluded from the Aires. It is ironic, given his televised harmonizing during the 2006 elections with Democrat candidate for Congress John Hall, formerly the lead singer for the band Orleans, that two of The Sing Dynasty's signature tunes were "You're Still the One" and "Dance With Me."

"Stephen sang lead on both of those, and supposedly this was all about Laura," said one of his fellow singers, who spoke to me only on the condition of anonymity. "Maybe that's why he was so enthralling when he sang them on TV. Maybe he was traveling back, thinking of her. Thinking of that leopardskin miniskirt she used to wear."

After D'Souza and then Ingraham graduated from the College, Colbert began to come into his own. Perhaps he was experiencing a sense of liberation. D'Souza, for one, thinks this is so. "The original Review team did cast a rather large shadow on those who immediately followed," he told me recently. "I think you can begin to chart Stephen's continuing ascension as a strong voice for the right to when The Review founders—his heroes, as it werehad left the scene and he began to think in original ways."

Two triumphs of Colberts senior year are especially worth noting. First, he was part of the brave band of Reviewers who launched the famous 1986 midnight raid on shanties that had been erected on the Green in an ineffectual protest against apartheid. The term that The Review used for its intrepid sledgehammer assault—"campus beautification"—is attributable to Colbert.

And then there was the dissertation that gained for him, finally, more than a modicum of academic success: honors in history. Spending long nights in Baker, an effort no doubt fueled by the animus he felt toward the College after nearly four years of abject misery, he researched how one person might make a difference- how one strong voice crying in the wilderness to philosophical kinsmen might make Dartmouth a better, more hospitable place. He found what he was looking for in an obscure, archaic, seldomnoted rule: the Agreement of 1891 that has lately gained so much notoriety. His paper, titled "Setting the College Right Again," was a 77-page explication of how a minority of like-thinkers could, over time and acting strictly within Dartmouth's rules of engagement, come to virtually control Dartmouth's board of trustees. "Colbert left a copy of that dissertation in the Review's archive," D'Souza disclosed to me. "He was not only proud of what he'd written, but he took it quite seriously. He thought his plan should be acted upon, and when he left the copy behind he said to the editors who succeeded me, 'You'll need this, one day.' 'As to what has happened, well, you connect the dots."

So at the end of the day-at the end of his stormtossed Dartmouth career—Colbert had found himself, found his voice and, in a way, found his mission. Yes, it had.been a trial on regular occasion, but finally worth the travail.

Or not to be.

Wah Hoo Wah Like some of His favorite Politicians, Colbert's first foray into Public speaking Came Not with a microphone, but a megaphone

Bear Truth Colbert majored in history but was adversely affect ty an unnerving freshman trip encounter with ursa minor.

The Right Stuff The budding pundit dabbled in pong and fraternity life, but only The Review (and a certain Reviewer) captutred his heart.

ROBERT SULLIVAN is the editorial director of LIFE Books. His previous works of nonfiction include Flight of the Reindeer: The True Story of Santa Claus and His Christmas Mission (Macmillan, 1996) and Atlantis Rising: The True Story of a Submerged Land, Yesterday and Today (Simon & Schuster, 2000).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

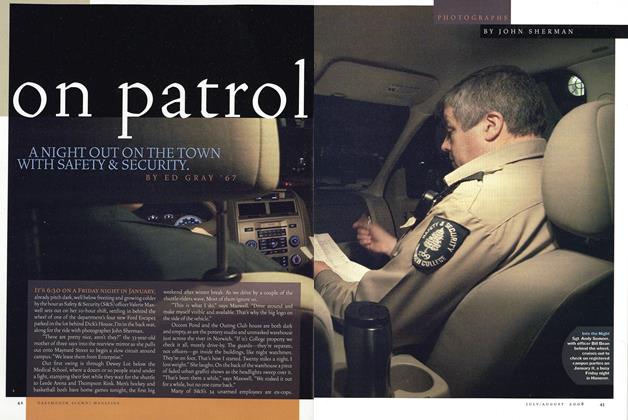

FeatureOn Patrol

July | August 2008 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

FeatureThe Artful Lodger

July | August 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2008 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2008 By John Kemp Lee '78 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July | August 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLearning Experience

July | August 2008 By Susan Marine

Robert Sullivan ’75

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

December 1990 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July/August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Sports

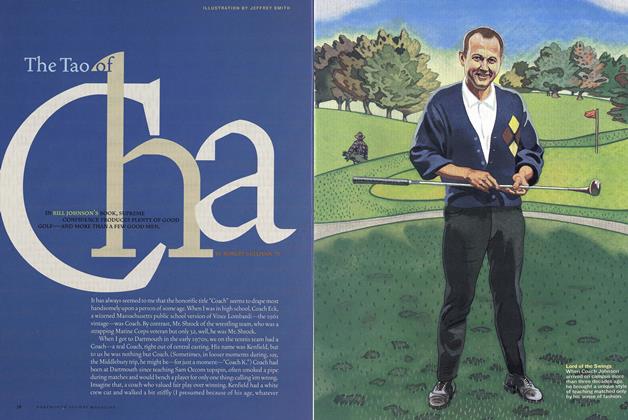

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May/June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

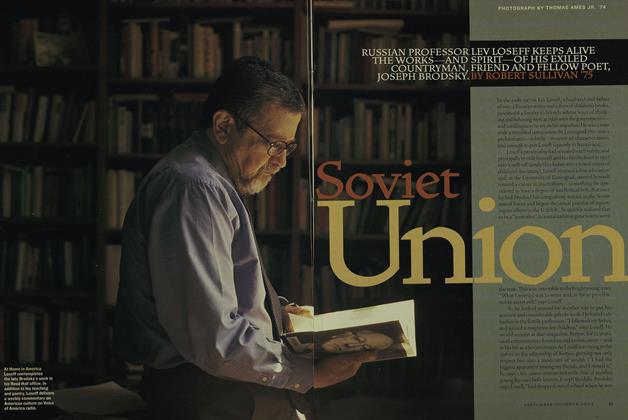

FeatureSoviet Union

Sept/Oct 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEHe Wept Alone

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureThe Glass of Fashion

December 1976 -

Feature

Feature"What We Are After"

May 1960 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Feature

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52