A MAN OF MANY ACHIEVEMENTS

WITH the death of Arthur Sherburne Hardy at Woodstock, Connecticut, last March there passed from this life a man long connected with Dartmouth College whose singularly diversified endowment of natural gifts had led him into at least four unrelated fields of activity, each of which he adorned. By turns he was soldier, teacher, diplomat and man of letters; and it would be difficult to determine in which direction his achievements had been most notable, since to each, with its wholly characteristic duties and special demands, he brought an equipment which enabled him to serve in all with unusual distinction.

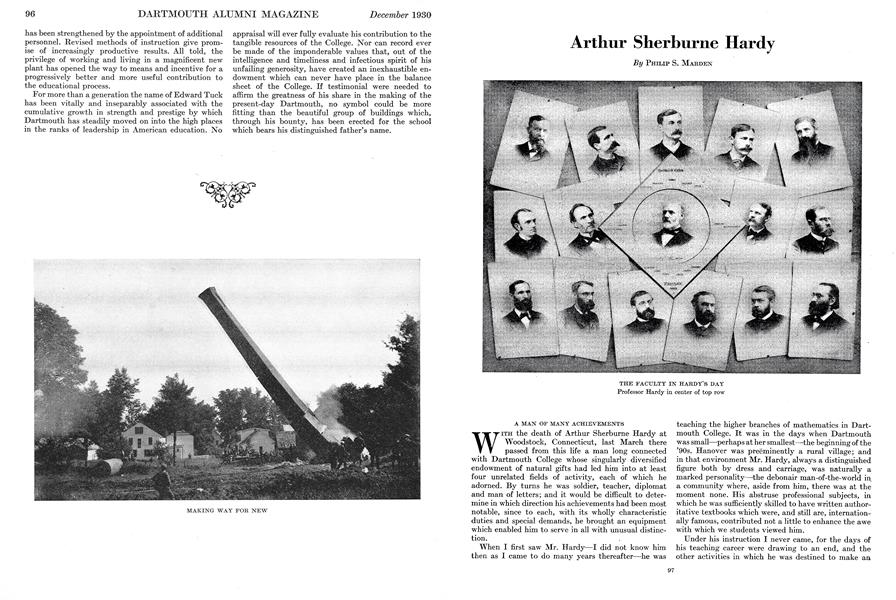

When I first saw Mr. Hardy—l did not know him then as I came to do many years thereafter—he was teaching the higher branches of mathematics in Dartmouth College. It was in the days when Dartmouth was small—perhaps at her smallest—the beginning of the '9os. Hanover was preeminently a rural village; and in that environment Mr. Hardy, always a distinguished figure both by dress and carriage, was naturally a marked personality—the debonair man-of-the-world in a community where, aside from him, there was at the moment none. His abstruse professional subjects, in which he was sufficiently skilled to have written authoritative textbooks which were, and still are, internationally famous, contributed not a little to enhance the awe with which we students viewed him.

Under his instruction I never came, for the days of his teaching career were drawing to an end, and the other activities in which he was destined to make an even greater reputation were just ahead of him. But from those who with his guidance investigated the mysteries of the Differential and Integral Calculus, Analytical Geometry and other exalted branches of mathematical science, one hears that he was a teacher of uncommon inspirational powers, capable of imparting to such intricate topics a most unusual clarity and interest.

A NOTABLE FIGURE

To me, and those of my time, he was an enthralling figure as he passed up and down the Hanover streets, unique among the professors of that day in that he had already written two or three extremely successful works of fiction. This fact also threw about him a panoply denied to his associates on the Dartmouth faculty. It was not alone that he had published magisterial works on "Quaternions" and "Analyt," sufficient to qualify him as among the most eminent mathematicians of his time; it was that in addition he had written such novels as"But Yet a Woman," "Wind of Destiny," and "Passe Hose." Such a man in the Hanover of that decade was ultra-notable; and from him, merely because we took note of his inescapable air of distinction, I am sure we all obtained a subconscious inspiration.

Besides, he was a "West Pointer"—and to boys there is always a glamor about that. Born in Andover, Massachusetts, August 13, 1847, a son of Alpheus and Susan W. (Holmes) Hardy, he had been appointed to the United States Military Academy from that district and graduated with the class of 1869. As the custom was in those post-bellum days he served a year or so as a lieutenant of artillery, being stationed in the Dry Tortugas; but his scientific bent led him in 1871 to resign from the army and to embark on the task of teaching engineering and mathematics, first at lowa College for a brief time and subsequently at Dartmouth—with an interval of preparation during 1874 when he took courses at Paris in the Ecole des Ponts at Chaussees which familiarized him with the scientific aspects of bridge-building and road-making.

His term as a professor of mathematics at Dartmouth extended from about 1875 to 1893, during which time he lived in the spacious house just at the foot of the hill on which stands the Medical School—the house which has latterly become the headquarters of the Graduates' Club, after serving successively as the home of Presidents Tucker, Nichols and Hopkins. It was the most eligible house in town and as such was usually selected as the place of entertainment for such distinguished guests as the College desired to mark with special honor, for whom Mr. Hardy was an ideal host; and from these experiences he derived not only personal pleasure, but also diverting memories of not a few curious notables with whom he thus came in contact, whereof it was his delight to relate stories in much later years.

My own single experience with him in those days related to an episode which perhaps I should be glad to forget. My class was in temporary disgrace because, in protest against what it regarded as undue exaction in the matter of studying the Iliad of Homer—or perhaps it was the Odyssey—it had paraded en masse by night before the home of its instructor and had serenaded that earnest personage with horns and other instruments of barbaric music. For this offense we were summoned in a body to the inquisition and assembled in the North Mathematical room in Wentworth Hall, where we found seated on the dais none other than Professor Hardy—the one man in all Hanover of whom we stood in genuine awe.

His task was not to examine individual culprits but merely to preside and to call each one of us in turn to proceed to another room for question. As luck would have it, the first card he picked up bore the name of the most outstanding scapegrace among us; and naturally the calling of the name evoked instantaneous response in the form of shuffling the feet, in what was then called the process of "wooding up." At that point out flamed all the army martinet in Mr. Hardy's make-up and the blast we got from him sufficed to shrivel us to the last man. There wasn't a whisper after that; and as boys invariably respect any one who knows how to master them, any of us would have gone to the stake for him thereafter. When a year or so later he offered a short series of lectures on Aesthetics we all turned out to hear him; and while these talks were far over our immature heads, there was in them a revelation of the finer things of life and of the appreciations to which a cultivated person might attain which remains with many of us to this day.

THE DRESS SUIT RECITATION

One other tale concerning disciplinary difficulties at Hanover Mr. Hardy used to tell with apparent joy. In those days Dartmouth students were seldom to be accused of attempting to be the glass of Fashion, but in his class was one young man whose studied disarray surpassed all the rest and became so pronounced that one day the professor inquired if he thought such negligence respectful toward either the College or its faculty. The response to this tactful hint was the appearance of the culprit next day in full panoply of evening dress for the forenoon class in mathematics. Mr. Hardy made no comment, but searched for the most intricate and difficult problem he could find, which he sent this gorgeously arrayed student to the blackboard in solitary state to demonstrate. Needless to say this unexpected publicity revealed something more than mathematical ignorance; and as it is always gratifying to see an engineer hoist with his own petard the class enjoyed itself to the full. And of course the ultimate outcome was a greater reverence on the part of all hands for the sartorial golden mean. Never again was there an attempt to get a rise out of the professor.

Mr. Hardy's contemporaries in Hanover have greatly diminished in number with the lapse of years and probably not more than three or four now remain who recall his life there. His more intimate acquaintances were probably the late Professors John King Lord—his nearest neighbor, with whom he went fishing and hunt ing—and Thomas W. D. Worthen. One of his surviving associates remarks, "Hardy was, I think, the most brilliant man I have ever known; polished and particularly delightful with such as he chose for his friends. He made mathematics fascinating to men of real ability. He was extremely well read, spoke French fluently, was sufficiently expert in matters of art to make him an agreeable lecturer and had attained celebrity as a novelist. He played chess and tennis well. Apparently his princ iples would not allow him ever to say a disagreeable or brusque thing."

My class was in its junior year at Dartmouth when, in 1893, after nearly twenty years of service, Professor Hardy resigned from the faculty and determined to devote himself to literature alone. His venture as successor to William Dean Howells in the editorship of the Cosmopolitan magazine, then published by John Brisben Walker in New York, proved not to be alluring enough to retain him in that particular field beyond 1895—fortunately so, no doubt, because when released from the drudgery of editorship he was free to enter on the diplomatic career which brought him so much additional distinction in the years that were to come. This began when he was sent by President McKinley in 1897 to represent the United States at Teheran, the capital of Persia—a bizarre post which provided him with a wealth of interesting reminiscences later embodied in his entertaining volume, "Things Remembered," which he published in his latter years and which also contains abundant recollections of other diplomatic assignments. It was while thus employed that he married at Athens, Greece, Miss Grace Aspinwall Bowen, a sister of Mrs. Rufus Byam Richardson. The latter's husband had been a colleague of the Dartmouth faculty as the professor of the Greek language and literature, but was then serving as the director of the American School at Athens. For a year longer the Hardys remained at Teheran, but in 1899 the government transferred the minister to Athens, where he served in highly agreeable and familiar surroundings until 1901—this post including the ministry to Serbia and Rumania also. To this period, I think, belongs the little volume, "Songs of Two," less familiar than some of Mr. Hardy's other works, but illustrating the extraordinary diversity of his literary genius.

He was advanced from the Athenian post to the ministry to Switzerland (1901-1903) and thence to the important legation at Madrid, where he served until 1905, at which time he retired from the diplomatic corps—the remainder of his life being devoted to leisurely travel and to the writing of various books and short stories of unusual distinction, the scenes of the latter laid principally in southern France. "Things Remembered," above referred to, was not only his last, but also in many ways his most important work and forms a thoroughly absorbing record of his life experiences.

Limitations of space inexorably demand resistance of the impulse to quote from so rich a mine of anecdote and reminiscence. It must suffice to say that in "Things Remembered" Mr. Hardy set down, in his delightfully readable way and without too much regard to formal or chronological arrangement, a record of what occurred to him as he wrote. This was by no means a chronicle of his diplomatic adventures alone, although such provide the bulk of the contents of the volume and naturally the most colorful portion of it. There are little sidelights here and there on his boyhood, the life at West Point, political relationships, and not a little sage comment on those enterprises of great pith and moment with which he came into contact; but principally, and to my thinking most charmingly of all, intimate accounts of experiences and people met with in odd corners of Europe, whether on official missions or on pleasure bent. It forms a delightful and likewise informing commentary on the long series of years during which it was vouchsafed Mr. Hardy to be active of mind and body, but most of all with respect to the decade in which fell his diplomatic experiences ranging from the Caspian to Gibraltar.

THE DOROTHY RICHARDSON LETTERS

The later short stories, many of them collected in "Diane and Her Friends" and not infrequently devoted to amusing problems of French criminal investigation, were of course in a mode differing both from that of "Things Remembered" and from those of his early novels, but suffice to reveal the versatility of his literary gifts and the broad scope of his genius. Not the least delightful of his more recent publications was the little volume embodying the letters which many years ago passed between himself and Professor Richardson's little daughter, Miss Dorothy Richardson, now Mrs. George C. Lincoln of Worcester, Massachusetts, in the days when she was a small girl in Athens and had not yet become Mr. Hardy's niece. Chiefly interesting to intimate friends who knew both parties to this interchange of "A May and November Correspondence," this tiny book must none the less reveal to others the sweet and kindly nature which so endeared Mr. Hardy to a host of friends.

It was in 1910 while returning from Italy that I first came to know him well, as one learns to know people whom one meets by chance while voyaging in the same ship. I found to my great reassurance that the episode of the North Mathematical room had passed completely from his mind and that on the frequent occasions when motor journeys led me to Woodstock, the Connecticut home of Mrs. Hardy's family, I could be sure of a cordial welcome and an hour or two of delightful conversation by pausing at his hospitable house there. I have known few men who have carried their years more lightly than he, or who, at 80-odd, retained a livelier interest in the events of the time. Encroachments of bodily illness impaired not at all the activity of his mind, enriched as it was by a ripe experience in the world of interesting events It was a friendship which I cherished highly, among many which it has been my good fortune to form with much older men, and the passing of it, through Mr. Hardy's death, leaves me the poorer for its withdrawal.

Having first seen him in a Hanover environment I always think of Mr. Hardy as a Dartmouth manwhich of course he was not, save by adoption. I fancy he did not think of himself so at all, although he often spoke of his life in Hanover and of the men and women he had known there. He was a West Pointer, first and last, and justly proud of it. From Dartmouth I believe he held only the honorary degree of Master of Arts, conferred on him in 1873, lowa College having bestowed a similar distinction in the year preceding. Amherst in 1873 also awarded him the degree of Doctor of Philosophy—a reminder that he had started in collegiate life as a student at that excellent college, from which he ran away abruptly in an impetuous attempt, thoroughly characteristic of his nature, to enlist as a soldier for the Civil war. This rash enterprise was frustrated by the intervention of his family, who apparently decided that if he was so keen to become a warrior the best way of insuring his doing so with a proper equipment of age and experience was to go through the Military Academy.

I doubt that there was ever a more charming companion, socially, than Mr. Hardy. His interests were so varied as to make him fit admirably into any group of men or women. In his earlier years he had been an enthusiastic fisherman, as were so many of his colleagues at Dartmouth in the 'Bos and '9os; and he was also expert with the rifle, as became an army man. During his diplomatic period he was among the pioneers in introducing golf as a sport in countries where it was not known—and not the least amusing of his chapters in "Things Remembered" relates to the anc ient and royal game as played over the improvised links in the shadow of Hymettus by himself and sundry confreres of the diplomatic corps then stationed at Athens.

There are characteristics which so predominate in some few among us as to cause some word or phrase to leap to the mind at the thought of them. In Mr. Hardy's case I think the instinctive thought would be of the cultivated gentleman—the term that always recurs at the thought of him or the mention of his name. Selection of any one quality in a man so abundantly endowed with aptitudes in such diverse fields would be embarrassing, but "cultivation" may suffice to blend them all. His membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters testified to the broad scope of his activities. Would that our diplomatic corps were more frequently recruited from the ranks of such men ashe—which unfortunately it is not!

. Reminiscences of Mr. Hardy as published by the intimates of his West Point days indicate that his literary gifts flowered early. There is extant an address delivered by him during his cadetship on the Fourth of July—a task which apparently fell to him because of evidence that he was likely to discharge it well—which could serve as a model to be followed by other orators on similar occasions as showing how, by one with unusual gifts, the overworked banalities may be avoided. But banality and the commonplace had no part in Mr. Hardy's equipment, whether in early youth or in the mature age to which it was permitted him to live.

Among those same West Point recollections also is to be found a poem written for the fortieth reunion of the class of 1869, which is so aptly illustrative of the universality of his genius that perhaps no better close for this brief memorial article can be found than is afforded by a quotation of its opening stanzas.

The Fortieth Reunion (Class of 1869, West Point)

Silent the stars ascend the eastern sky; Nor summer calms nor winter storms delay Their fixed, irrevocable march As steadfast through the zenith's arch Unfaltering they hold their way Down the far western slopes where they must die.

So we, a little company of that vast throng That people for a span a dying sun, Climb for a while with laughter and with song Our little arc, and turn—a journey scarce begunDown the dark path where work and song are done.

'Twas only yesterday we first clasped hands; Today we stand within those barren lands That to our eager eyes once seemed so far, so fair; Tomorrow?—ah, give Memory the torch Hope's failing grasp no more may bear!

THE FACULTY IN HARDY'S DAY Professor Hardy in center of top row

CAMPUS DURING A POLITICAL CAMPAIGN IN THE EIGHTIES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe New Tuck School Plant

December 1930 By Dean William R. Gray -

Article

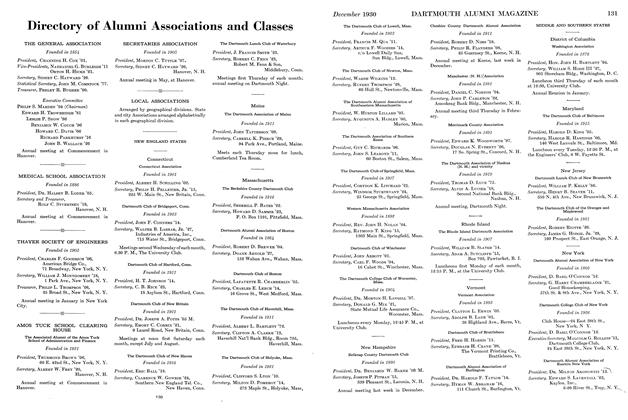

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

December 1930 -

Article

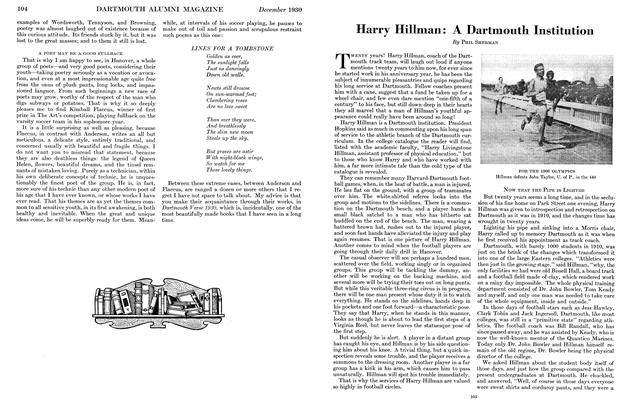

ArticleHarry Hillman: A Dartmouth Institution

December 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Lettter from the Editor

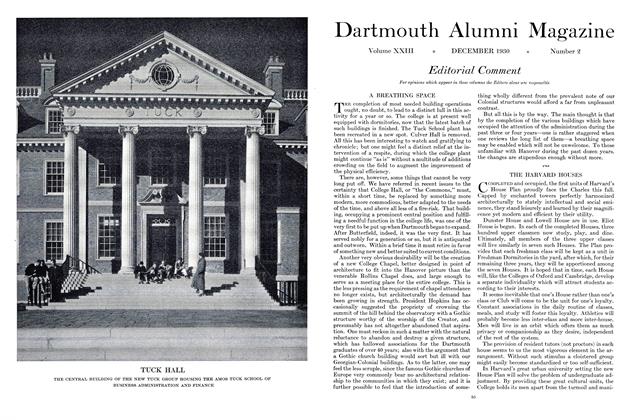

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

December 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson

Philip S. Marden

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

October 1951 By CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

November 1954 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

October 1955 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

January 1957 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

DECEMBER 1958 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894

December 1957 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL, WILLIAM M. AMES, PHILIP S. MARDEN, 1 more ...