THERE HAVE BEEN three main eras in the science of admissions to American colleges. First of these was the Mark Hopkins-Log period, with few colleges, very restricted curricula, and few highly selected candidates from homes of intellectual culture, when an ability to read with fair competence English and the Classics was a completely satisfactory criterion for admission. Then came the great and accelerated surge of secondary schools and colleges, which gave birth to two standardizing agencies —the Carnegie Entrance units and the College Entrance Examination Board—both of which have had a most significant part in our educational development. Finally, with the inauguration in 1921 of a Selective Process for Admission at Dartmouth College, a new note was struck and a new era begun, in which the sufficiency of the traditional standard college entrance requirements was questioned, and where distinct emphasis was placed on general and continuous scholastic accomplishment, on character, and on a candidate's general influence and reputation among his colleagues. The basic principles of this Selective Process, which were widely questioned at the time of their promulgation, are now the axioms upon which admission techniques are formulated, and their inception and successful operation constitutes one of Dartmouth's greatest contributions to education.

Although the Selective Process has been uniformly and increasingly successful, its administration has always been somewhat hampered by a certain lack of flexibility which was a remnant from the middle era. Dartmouth continued to have a set of prescribed Carnegie units, which, incidentally, had no particular connection with the curriculum of her freshman year. However, during the past decade certain elements of flexibility were obtained by various disjointed means. First of all, our Honor Certificate, adopted in 1920, made entrance easy for boys with consistently high scholastic ranks. Then each year a half dozen or so "exceptions were admitted from schools too small to be able to gain our certificate privilege and financially unable to coach boys for College Board examinations. The records of these boys without exception have been superior in college because they were superior boys when they were admitted. Again, each year President Hopkins has taken delight in regularizing a few,irregular credits upon the recommendation of the Director of Admissions, thus getting around technical difficulties for boys who obviously were ready for college. But finally, we have increasingly realized that our secondary schools, instead of being dominated in their curricula by the colleges, were now in the saddle and were educating boys by the thousands that the colleges could take or leave. It has seemed high time, therefore, if colleges wish to skim some cream from this large and valuable product of our schools, for them to wake up to what is going on and to articulate their admission techniques with facts and not with theories.

The Selective Process has long since demonstrated that no specific set of formal entrance units were sufficient evidence to insure selection for admission to Dartmouth College, but we have only gradually come to the conclusion that no such specific single set of units were a necessary condition for admission under our Selective Process. In other words, we came to the conclusion that a still greater flexibility in final admission units was advisable, and that the degree of this flexibility should be determined by the simple but fundamental doctrine that only two things were essential in determining who should enter Dartmouth College: first, that the candidate should possess that character, accomplishment, and personality which the Selective Process was designed to determine; and second, that his school history should indicate, both in content and accomplishment, that he was competent to proceed with the work of our freshman year.

The new admission policy at Dartmouth College, which will begin with the Class of 1938, tries to accomplish exactly these two things. In other words, we will welcome the applications of promising boys from all secondary schools throughout the country. They will be judged by the varied and rigorous standards of the Selective Process, and will be admitted if they belong to one of the many types we desire to insure a rich community life on our campus, and if their scholastic history and accomplishment indicates that they are prepared successfully to undertake our own curriculum.

It should be pointed out that at the present time scientific studies are being made which will greatly strengthen our Selective Process, because we hope that we shall be able to obtain accurate information on such extremely important qualities in our applicants as intellectual curiosity, creativeness, power and habit of analysis, reading ability, determination, and influence. Moreover, by modern objective and subjective tests, we shall be in a position to require, even more than we do now, evidence of a boy's actual preparation for our work.

Recently the distinguished headmaster of one of our great private schools stated that Dartmouth was the most difficult college in the United States for a boy to enter. Under our new policy it will be harder still for a poor college prospect to enter Dartmouth. We have changed our perspective and at the same time have raised the really vital standards which should determine admission to college. We have demonstrated that the old accumulation of credits which originally was a means, has long since become an end and for many years has been the curse of secondary education. In place of this shibboleth we have set up the ideal of real intellectual accomplishment during the secondary school period. It is dangerous to prophesy, but it is probably safe to say, that in much less than a decade most of our leading colleges will have accepted the principles of our new plant as axiomatic.

Director of Admissions

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

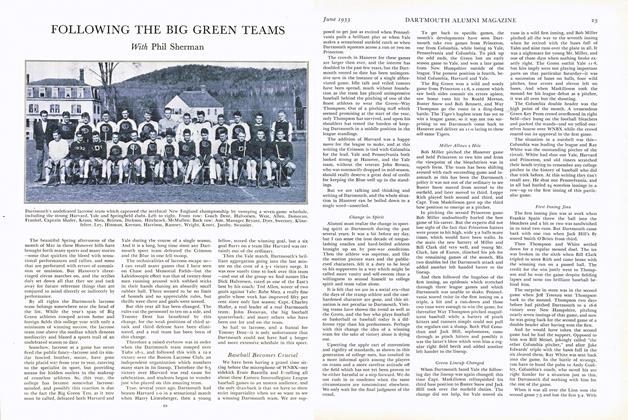

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

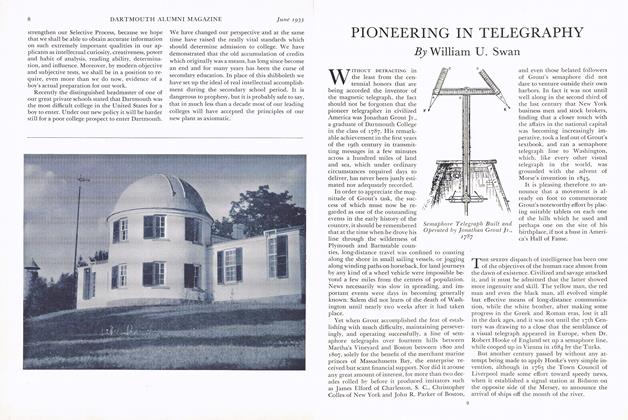

ArticlePIONEERING IN TELEGRAPHY

June 1933 By William U. Swan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933

E. Gordon Bill

-

Article

ArticleTHE NEW SELECTIVE PROCESS

January 1922 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

ArticleWHY DARTMOUTH?

February, 1923 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

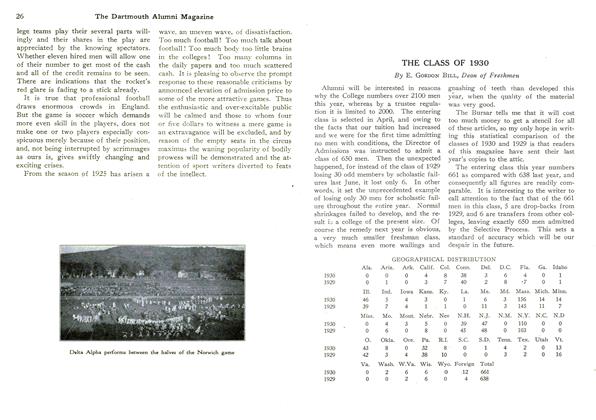

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

NOVEMBER, 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

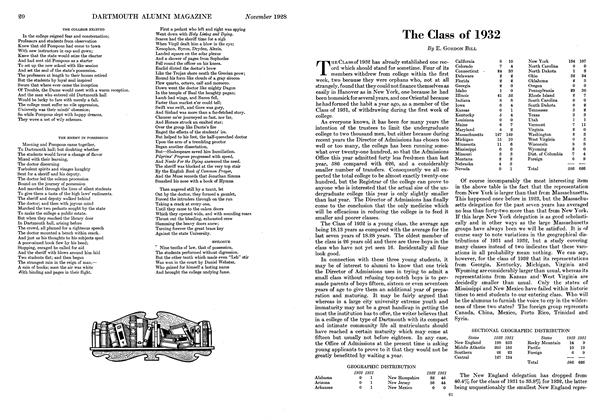

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

ArticleCURRICULUM VIVENS

March 1936 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

ArticleV-12 COURSES LIBERAL

May 1943 By E. GORDON BILL