I WILL tell you how it is with Chase," said Abraham Lincoln to a friend in 1864. "He thinks he ought to be President; he has no doubt whatever about that. It is inconceivable to him why the people have not found it out—why they don't, as one man, rise up and say so."

President Lincoln, who had at times an uncanny ability to correctly estimate the qualities and motives of those about him, was here speaking of Salmon Portland Chase, a Dartmouth graduate who rose to the highest judicial post in the land, but whose life was spent in a fruitless craving for the Presidency.

Following in the footsteps of his illustrious uncle, Senator Dudley Chase of Vermont, Salmon P. Chase entered Dartmouth as a junior at the age of sixteen, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa with the Class of 1826.

After a brief period in Washington, during which he conducted a "select classical school" and studied law, he removed to Cincinnati where he began his legal practice.

Early identifying himself as a staunch advocate of the abolition of slavery, Chase's efforts to protect fugitive slaves from return to their Southern masters soon caused him to be referred to as "the attorney-general for runaway negroes."

Turning to politics as a means of pressing the abolition issue, his early career was marked by frequent changes of party, and he advanced slowly until a deadlock in the Ohio state legislature in the winter of 1848-49 won him a seat in the United States Senate.

Upon. formation of the Republican Party, Chase joined that group and by the time of the convention of iB6O he had climbed so high in party ranks that he was, with William H. Seward, considered one of the two leading contenders for the presidential nomination.

That this recognition was quite generally accorded is attested by an excerpt from a letter written during the pre-convention period by Abraham Lincoln, then Congressman from Illinois. "What's the use," he advised a friend, "of talking of me for the presidency, whilst we have such men as Seward, Chase, and others."

But the cause proved to be not so hopeless as Congressman Lincoln believed, for on the third ballot, due to a shift of votes 'hat had belonged to Salmon Chase, he was given the nomination of the Chicago convention.

Chase was an extremely proud individual, and he was never to forgive Lincoln or, as he believed, taking the Presidency from him.

After the election he reluctantly yielded t0 the persuasion of Lincoln and accepted appointment as Secretary of the Treasury in the new Cabinet. He conducted his department and the financing of the war with great ability, but his subordinate status was humiliating to him, and as time went on he came more and more to resent his chief and to yearn for greater personal power.

Fancying himself quite an able military strategist (although admitting in his diary that he was far too near-sighted to distinguish himself in the field), Chase became a prolific correspondent with Union military commanders. He urged on many occasions that they disregard the strategy of their Commander-in-Chief and follow his own plans.

Nor was his criticism of the administration limited to expression before those in official circles. As the President himself once noted, he never failed to embrace and sympathize with those who felt that they had been "hardly delt with" by it.

Determined to win the convention's nomination in 1864, Chase from his Cabinet post smiled upon a secret canvass begun in his behalf early in the preceding year. Unfortunately, secrecy was not well guarded, and the activities prematurely reached the papers, suffering him to undergo violent public attacks for his apparent infidelity.

With Chase thus effectively removed from the field, Lincoln rode the crest of a great popular movement to unanimous re-nomination on the first ballot at Baltimore.

Relations between Chase and Lincoln were now strained to the breaking point. With bitterness over the nomination still fresh in his mind, Chase submitted another of his frequently tendered resignations when Lincoln sought to override an objectionable appointment in his department.

This was his last resignation, for much to his surprise, the President decided to compromise with his Treasury Secretary no longer, and accepted it.

Lincoln, however, was not long in reaffirming his long maintained confidence in Chase's ability, for upon the subsequent death of Roger Taney, the President nominated him to the Chief Justiceship of the United States.

Thus it was that three months later on Inauguration Day, Salmon P. Chase in the robes of his new office presented himself at the Capitol to administer the oaths of office to Mr. Lincoln and his Vice President, Andrew Johnson.

After Vice President Johnson had been sworn in in the Senate Chamber, the official procession made its way to the inaugural platform before the Capitol where Abraham Lincoln recommended to his countrymen that "with malice toward none; with charity for all" they "do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations."

As Lincoln finished his address and the Chief Justice began administering the oath, rays of brilliant sunshine pierced the darkened sky which had been overcast all morning, and shone brightly upon the two men.

In later forwarding the Bible used in the ceremony to Mrs. Lincoln, Chase made note of the occurrence and expressed the hope that it might prove "an ospicious omen" for the days ahead. But this was not to be, for in little more than a month a bullet from the gun of John Wilkes Booth claimed the life of the man from whose lips those words of humble entreaty had issued.

Chase had retired for the night when word of Lincoln's assassination reached him, and he described the intervening hours before dawn as "a night of horrors."

The next morning he was "up with the light" and at eleven was summoned to the Vice President's rooms in the Kirkwood Hotel, and there swore in Andrew Johnson to succeed to the Presidency.

Here was the strange paradox of the genteel and scholarly Chase serving as the instrument by which a Chief Executive was made of the one-time tailor from Tennessee who had not learned to read with ease until he entered the Halls of Congress.

Of the small group that witnessed the simple ceremony, it is not unlikely that some reflected that it would have been more appropriate were it Chase who was receiving the oath rather than giving it.

Although they were never to meet again on an inaugural platform, this was not the last time that the Chief Justice was to officially minister to President Johnson.

The Johnson administration was a stormy one. Relations between the President and Congress became worse and worse until, due to his direct defiance of the newly passed Tenure of Office Act, the House resolved to impeach the Chief Executive, and on March go, 1868, Chief Justice Chase was called on toj>reside over the legal proceedings in the Senate.

Though he had no particular liking for Johnson, and personally opposed many of his policies, he took no comfort in having to partake in the trial. "To me," he said, "the whole business seems wrong

What possible harm can result to the country from the continuance of Andrew Johnson—months longer in the presidential chair, compared with that which must arise if impeachment becomes a mere mode of getting rid of an obnoxious President."

But on May 16 the Chief Justice listened as the members of the Senate answered the roll to vote on the final article of impeachment, and then arose and declared, "Two-thirds of the Senators not having pronounced guilty, the President is acquitted upon the eleventh article."

This article was that on which most of the sentiment in favor of conviction was centered, and despite subsequent attempts at dragooning votes, no ground was gained and the proceedings were dropped.

Although he had by now lost much of his political following, Chase was still suffering from what President Lincoln had termed his "presidential fever," and with the unpleasant trial of Johnson over with, he sef about preparing for the campaign of 1868. *

There was little hope of anyone other than the immensely popular General Grant securing the Republican nomination that year. Chase's cause was, therefore, pressed by his friends within the Democratic Party in an attempt to make him' their standard bearer. But the effort failed, and New York's Governor Horatio Seymour was tendered the dubious honor of opposing the Civil War hero.

As had been expected, Grant took the country by storm in the November elections, and on the dark and drizzling March 4 that followed Salmon Chase installed him as the eighteenth President of the United States.

Here was a man who had been given, unsought, that which Chase desired so strongly nearly all his life. A man who, in fact, had he not been called away from a theatre appointment with President Lincoln nearly four years before, might not then have been receiving that oath.

The inauguration was a gala occasion. Washington was full to overflowing with people from all over the country come to witness an event of color and pomp that included a cavalry escort, brass bands and buglers, and more than its share of tall hats and gold braid.

In reporting on the inauguration TheNew York Times noted, "Chief Justice Chase appeared very nervous. He fumbled with the paper on which the oath was written, and he was far more embarrassed than President Grant."

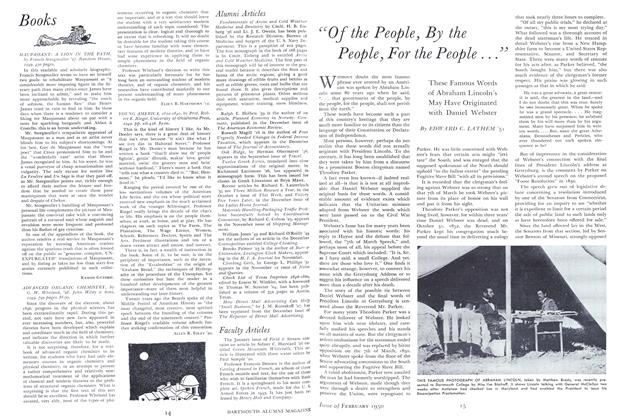

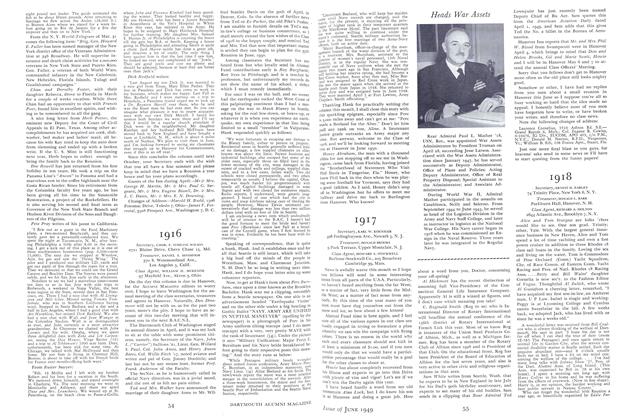

It seems somewhat foolish to assume however, that it was some form of stage fright that the high jurist was experiencing, for he had previously been before too many public gatherings. He certainly gave for instance, no indication of stage fright as, in his capacity of president of the Dartmouth Alumni Association, he presided over the College's centennial celebration later in that same year.

It is more probable that his uneasiness on the occasion was fostered by the disagreeableness to him of this duty of his office.

While not violently opposed to Grant at the outset, Chase's regard for him was only passive at best, until early in 1870 when there developed a wrangle over the Court's decision, as handed down by the Chief Justice, that the Legal Tender Act of 1862 was unconstitutional.

The President shortly made appointments to two existing vacancies within the high tribunal, and when these Justices cast the deciding votes in a reversal decision in a new test of the law, a loud cry of "court packing" went up across the country.

This controversy was still much in the national spotlight when, on August 17, Chase suffered a severe attack of paralysis. His recovery was slow, but he was a man not easily defeated, even by ill health, and by the beginning of the 1871-72 term he was sufficiently well to take his seat at the head of the Court once more. Through this term and the one that followed he did not miss a day at his post.

But by the time of Grant's second inaugural on March 4, 1873, the Chief Justice had grown noticeably weaker and had begun to tire easily. He performed his part at the inauguration with resignation. He first administered the preliminary oaths, and then watched as a three-man committee, two members of which were holders of honorary degrees from Dartmouth, escorted the President to the platform. There he gave him the oath of office and held the Bible for the bearded Grant to kiss.

Chase's condition grew steadily worse, until on the last day of the Court's term, he was forced to turn the session over to Justice Clifford, and sat throughout the day with his head in his hands. On May 6, the Chief Justice suffered a second stroke and died the following day.

Less than a month from the closing of the term, Chase's body was returned to the Supreme Court chamber and laid on the same catafalque that eight years before had born the remains of Abraham Lincoln, that the nation might pay tribute to an able public servant, but one whose long career was spent in passionately •no- that which he never quite attained.

Perhaps Chief Justice Chase had really died more than two and a half years be- fore at the time of his first paralyzing at- tack, for it is reported that it was not until then that he finally realized that he would never live to be called "Mr. President," nor add that title to the distinguished list which included Governor, Senator, Sec- retary of the Treasury, and Chief Justice of the United States.

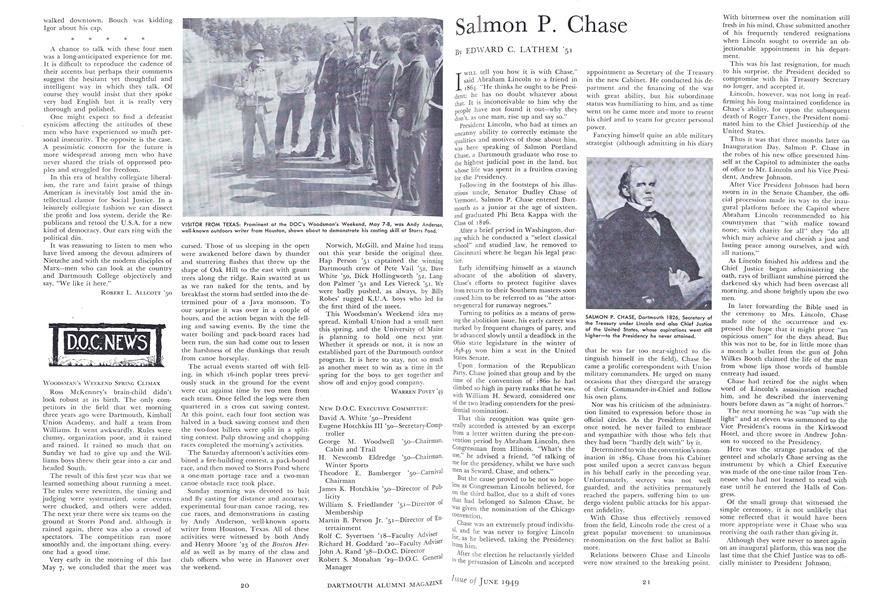

SALMON P. CHASE, Dartmouth 1826, Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln and also Chief Justice of the United States, whose aspirations went still higher—to the Presidency he never attained.

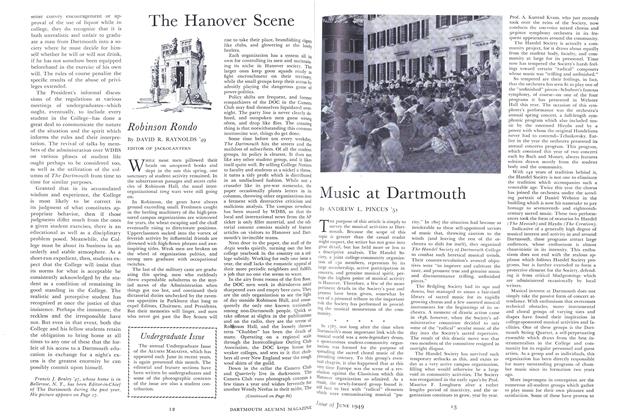

STUDENT AUTHOR: Edward C. Lathem '51 of Bethlehem, N. H., whose delvings into Dartmouth history produced this sketch of Salmon P. Chase, 1826.

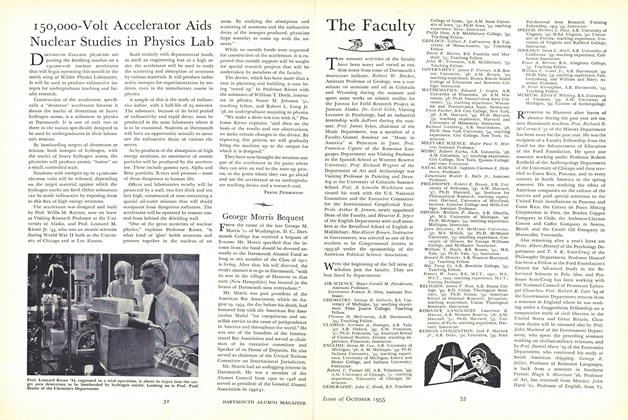

DARTMOUTH CENTENNIAL IN 1869, at which Salmon P. Chase, as president of the General Alumni Association, acted as presiding officer. He was also the principal dignitary present at the exercises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMusic at Dartmouth

June 1949 By ANDREW L. PINCUS '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

June 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1949 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ALBERT E. M. LOUER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1949 By Robert L. Allcott '50

EDWARD C. LATHEM '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleGeorge Morris Bequest

October 1955 -

Article

ArticleFlux-tour

JAN./FEB. 1979 -

Article

ArticlePresidential search committee named

DECEMBER • 1986 -

Article

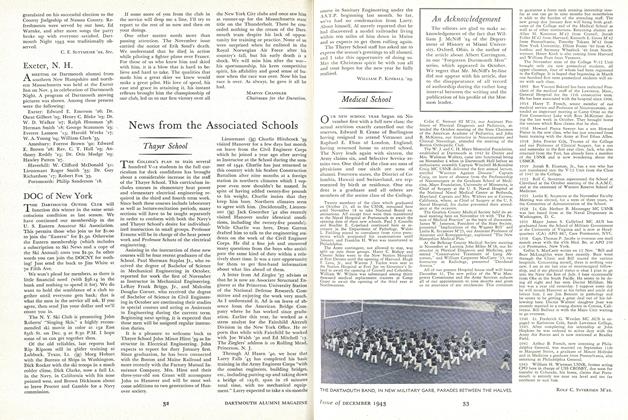

ArticleWith the Debaters

December 1938 By C. J. Stratton Jr. '41. -

Article

ArticleProfessor Katharine Gingrass-Conley:

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMedical School

December 1943 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22