DEAN OF THE FACULTY

A FEW weeks ago when you were sitting in the balcony rather than on the floor of this hall President Dickey spoke at Convocation. At the end of his address he said, "Your business here is learning, and that is up to you." All through your four years at college, and after, remember that admonition: it's up to you. You may have heard the story of the old maid who became aware in the middle of the night that a man was standing beside her bed. With fear, though perhaps with some hope, she spoke to him. "What are you going to do to me?" "That's up to you, lady," he replied calmly. "It's your dream." What you are going to make of the college, the curriculum, and the faculty is up to you. Dartmouth is the dream of every individual one of you, to realize as you wish.

You have come to college for a liberal education - and some of you are going to get it. Just what does that hackneyed term mean? For many years now, in school and out, you have probably heard the phrase "liberal education." It is something one is supposed to approve of, like "the American way of life" or "the public-spirited citizen," but no two people agree precisely on what is meant. So the chief reason for the vagueness you probably feel about the term is not really your own ignorance. It is that the term itself has many shades of meaning, and while most men would agree on essentials, each would work into it his own particular emphasis.

A liberal education is really an ideal toward which men of good will, intelligence and sensitivity are always struggling. Even though no two men would probably agree precisely on all the qualities that a liberally educated man should have, let us see this evening if we can outline a few on which there would be general agreement.

In the first place, the liberally educated man has a mind that is a rational, disciplined instrument, that knows the difference between fact and opinion. He knows a good deal about nature and a good deal about human beings, but he also has the intellectual humility to realize how limited his knowledge really is. He is ready to act on his convictions, but because he knows they are only tentative, he is tolerant of the opinions that oppose his own. He expresses himself well and with clarity because he has a feel for language and a respect for it. When he speaks, he controls his voice and puts the minimum strain on people listening to him. When he writes he observes the code of good manners in spelling, punctuation and diction. His outlook is not limited to one culture alone. He is familiar with at least one other language which will give him an insight into another way of thinking and another culture that is denied a completely monolingual person. The educated man, then, has a mind that can think, a mind that is open. He knows what evidence is, where to find it, how to put it together and think about it, and how to draw conclusions from it. And once he has arrived at a conclusion, he knows how to communicate it or put it into action.

Above all, perhaps, and this is very intangible, he has achieved a feeling for quality. Because he has quality himself he is able to sense quality when he meets it, whether in music, painting, or some of the other arts, and, perhaps most important of all, a feeling for quality in his fellow men. He knows a good man when he sees one.

The concern of this college with the nurturing of liberally educated men can be summed up very quickly by the statement President Emeritus Hopkins made some years ago. He said, "The primary concern of the. College is not what men shall do but what men shall be." The social aspect of that ideal is pointed up in President Dickey's statement that Dartmouth's first responsibility is "service to society," and to turn out men who have both the "competence and conscience" to take worthy places as free men in a free society. And in no period of history have those qualities been more desperately needed than in our own.

Another quality which I haven't mentioned, but which I must here, is intellectual courage. Thinking is about the hardest and most upsetting activity in which a man can engage. Some of you who have read John Stuart Mill remember that he posed this question: Is it better to be a fool satisfied or a Socrates dissatisfied? The man who pretends to a liberal education has made his choice. As against the moronic tranquility of a vegetable existence, he has the intellectual courage to come to grips with some of the fundamental and unanswerable questions of human life and make his peace with them.

For a few minutes now, I should like to suggest to you a few of those fundamental questions that confront every cultured person. It has been said that an intelligent man knows how to ask a question and an educated man knows what questions to ask. If that is true, there is perhaps a corollary that a good test of the right question is that it is always one to which no one knows the answer.

HERE is a question with which every man must somehow make his peace, if only by running away from it or ignoring it. What is the relationship of man to the Absolute? By Absolute, I mean his conception of God, and with it his convictions on the religious issue. Is there a Cosmic Intelligence or Divine Being, and if so, what is man's relationship to it or Him? It is a question much older than history. Every one of the religions of the world and every one of the various Christian sects has a different answer to it. As has the atheist. In the past men have fought wars and systematically tortured one another because they disagreed on the answer to that question.

In English I all of you are now reading selected portions of the Old Testament. The Old Testament, written by many authors, is the record of the passionate quest of an ancient people for an understanding of the nature of God. Each author portrays a different concept. Men will always be searching for some answer to that question. For our Christian society I might point out that Western man for 1000 years accepted an infallible church as the custodian of the true answer. After the great period of history we call the Renaissance, the Christian world was split into two parts, one Catholic, one Protestant, with the Catholics accepting the word of the church as the ultimate answer and each sect of the Protestants accepting a different interpretation of the Bible. Then about 150 years ago came the industrial and scientific revolution, and the coming in of men who declared that truth was not to be found in any Divine revelation but by the methods of science. And no understanding of modern history is possible without an understanding of the effects of this growth of secularism. The religious question, using the term in the largest sense, has always haunted men and always will. A mark of the educated man is his awareness of a multitude of answers that can be given to the question and his own intellectual courage in finding his own way of living with it. An unthinking acceptance of the religious creed of a group is not a real answer. As Whitehead pointed out, "Religion is what a man does with his solitariness." The educated man knows that he can never arrive at a final answer, but he is capable of constant growth in spiritual power.

Discussion of that issue will come to you in college rather directly in courses in religion and philosophy, and in many works of literature. Moreover, it is inevitably implied in every course you take, just as it will be implied in every major decision you make. It is a question that in the last analysis cannot really be evaded or ignored.

LET'S look for a moment at another question any liberally educated man has got to come to terms with. Let's keep it in the same pattern. What is the right relationship between man and his fellow men? Of course, every religion has a guide to one aspect of that question in its version of the Golden Rule. But the question is more complicated than that. If I may refer once more to your work in English I, you remember that in the 4th chapter of Genesis we learn that Cain murdered his brother Abel. When God questioned him and asked, "Where is thy brother Abel?", Cain answered, "Am I my brother's keeper?" You will recall that God did not answer Cain's question. And it has had to be resolved by men in every generation, not only as individuals but as nations. In our generation, the terrible crisis we have gone through has shown us in dramatic form an answer that ethical philosophers have always asserted, that we are our brother's keeper not only for our brother's sake but also for our own. In our cities we find that the clearing of slum areas is necessary to protect the better residential areas against disease and crime as well as benefit the slum dweller. In international affairs it has been found necessary to give up a comfortable isolationism and to assist other nations, not in charity but in selfdefense.

But that aspect of the question is relatively clear-cut compared with the issue involved in the question of what is the best political structure, and what is man's relationship to the state. What forms of community life and government best fulfill the needs of man? What is the most practical and most moral economic system? The Communists know that they have the right answer. Just as certainly we know they are wrong. In this particular juncture of history we, in this section of the world, have come to accept for ourselves political democracy and a modified capitalism in economics. Even so, within that framework of acceptance we are frantically trying to solve such problems as those presented by minority groups, the question of the individual's loyalty to the state, and what are the rights and responsibilities of labor, management, and consumer. Politics have come to embrace more and more facets of our lives. Thomas Mann once wrote, "Ours is a political age and the destiny of modern man will be decided in political terms." Certainly we know that with the weapons for destruction we now possess, unless we can achieve some way of living at least in mutual tolerance, the future is none too bright.

There are dozens of aspects of the basic question of man's relationship to his fellows that will always perplex man. Other animals - the bees, the ants, the birds for example - have all arrived at a fixed pat- tern of social behavior. It is part of man's tragedy and surely even more part of his glory that he has not.

So that is another question the liberally educated man has got to have explored, not for an answer, but to find some tentative convictions, based on wide reading and open-minded thought. In this field particularly the educated man knows the difference between fact and opinion, and, what is more difficult, knows the difference between a reasoned conviction and an unreasoned prejudice. For example, he doesn't classify himself as a Republican or Democrat because of acceptance of slogan thinking or inherited prejudices. On the basis of his own values he has analyzed the policies of both parties, accepted one, rejected both, or was unable to find any basic difference. But he has accepted his political responsibility not only as a citizen but as a liberally educated man.

What about man's relationship with nature? Like the others that question can take many forms, one of which is just the sheer enrichment and enjoyment of human life. I have been shocked by students at Dartmouth, up here in the North Country, who can't even point out the north star, who have no understanding of the concept of an exploding universe, who have never really looked at a number of snow flakes, who know nothing about the habits of birds and wild life. A hundred years ago Thomas Huxley wrote, "To a person uninstructed in natural history, his country or seaside stroll is a walk through a gallery filled with wonderful works of art, nine-tenths of which have their faces turned to the wall." To forego at least a slight understanding of other animal and vegetable life, and of the laws of physics, chemistry and anatomy that govern us is to live only partially. A liberally educated man will turn at least some of those pictures around.

Or take another aspect of that question. It is pretty sobering to realize that in the past thirty years we have used up more of the earth's irreplaceable mineral resources than were used by men in all previous history. How long can we continue this rape of our natural resources? Is this generation acting responsibly in its relations with nature, or are we on a drunken spree which will give our children a terrible hangover? I don't need to go into the awful problems raised by atomic energy.

I SHOULD like now to refer to one more question of that sort, because I think it is the most basic of all. We shall keep it in the same form. What is the relationship of man with himself? For any individual man society is always on the circumference, and the groups of which the individual is a part stretch out in ever widening rings from the center where he is. He is part of a generation in the world, part of a nation, part of a town, part of a business, part of a social group, part of a family, and then finally and most importantly, he is himself. As the radius contracts to that final point the individual is finally confronted with nothing but himself and his own code of values. Some years ago in the Great Issues course Mr. T. V. Smith phrased the central question brilliantly. He asked, "If you call on yourself, will you find anybody at home?" Robert Frost put a slightly different slant on the question when he said, "Every man must learn to contain his chaos." It is obviously a question that embraces aspects of the other questions I have been talking about. By adjusting his relations in other directions a man can learn to contain his chaos. He can do more. He can make himself such a man so that when he calls on himself he may find an interesting companion. All these questions I have been talking about are meshed with one another. How the individual comes to terms with himself is not only a personal question but may affect all of society. As Confucius once said, "A man cannot be at peace with his community unless he can establish peace with himself." Adolf Hitler is a striking example of a man who could not achieve peace with himself - and the results have affected you and me.

What we are concerned with here is what kind of a man a person is, what are his values, his sensitivities. Immediately after the war a returned veteran wrote this paragraph as part of a paper in English:

It was a cold January morning when we entered the outer harbor of Le Havre. The sunrise was an unreal red, the water a clear and fantastic green. The sunrise would soon be gone - the water would soon be black. And, as if to capture the moment, some American Gl's on board ship were putting razor blades into chunks of bread and throwing them to the waiting seagulls. Loud outbursts of laughter sounded as surprise would come and a throat be cut. That was Le Havre - red sky, green water, and razor blades.

That soldier's captured moment, crisp, vivid, bitter, illustrates the gratuitous cruelty of men who have not contained their chaos. It also highlights a problem that goes to the heart of our time, or any time. How much of the agony and tragedy of the world comes from the warped moral judgment that springs from such fundamental insensitivity of individual men, multiplied by millions? Some of the hard facts of contemporary life, racial hatreds, the corruption of men entrusted with public office, the inhuman aspects of a mechanical civilization, the welcoming of war or other forms of destruction as an outlet by emotionally and imaginatively under-privileged men, are all possible because of the number of individual men who, if they were to call on themselves, would find someone at home that would surprise them.

In this area of thinking we are really getting at the core of the meaning of a liberal education. I remind you again of Mr. Hopkins' statement: "The primary concern of the College is not what men shall do, but what men shall be."

Let me put it this way. Much of our conduct as individuals is governed by law. In certain areas society has laid down absolute rules for conduct, laws against murder, theft, driving while drunk - laws which must be enforced to make organized society possible. One obeys those laws, hopefully from an internal rather than an external compulsion. There is another area in which there is absolute free choice. What a man shall eat, what he wears, what movies to see and which to miss, what sport to indulge in, what TV program to turn on. The crucially important area for the liberally educated man comes in between. It is what has been called the domain of the unenforceable that lies between law and free choice. In that area he is really tested. There he has no external compulsions, but only those of his own values, of his own integrity as a human being. In that area his decisions tell you what he is. There a man has to decide for himself whether he will take advantage of someone else's helplessness, whether he will take a finesse after he has inadvertently seen the king in one opponent's hand, whether he will follow wounded game for miles in order to put it out of its misery, whether he will write that letter home that means so much to his parents. There in that area is a real test of a liberal education. Has it made a man who can join what E. M. Forster calls "the aristocracy of the intelligent, the sensitive, and the plucky?"

A truly liberal education makes you aware of all these issues and many more. They really can't be studied separately. The human being and his values can't be chopped up into segments. The relationship a man establishes with what he conceives to be the Absolute may well determine his conduct in his associations with himself, and the two may determine his basic relationship to society and nature.

There are a great many other questions we could propound in the same way. For example, an interesting one might be, what is the right relationship between a man and a woman?

BUT the hour is going on. What I have tried to give you is an indication of some of the questions and of the complexity of the adventure of the liberal education you are undertaking. For the rest of the hour let's talk about the curriculum that is designed to give you a start toward the goal, working toward which you will, hopefully, spend not only four years of college but the fifty years after that.

We have provided for you, as you know, required courses. We insist that you attain a certain competence in the use of your own language and some training in your ability to appreciate the great heritage of its literature. So English 1-2 is required, unless you have already shown you have that competence. We insist that you have at least an elementary comprehension of a foreign language, as a guide to understanding your own, and as a means of giving you an insight into a different culture. We introduce you to the question of man's relationship to nature by requiring you to take at least four courses in the natural sciences. No man today can consider himself educated unless he has some understanding of the processes of arriving at scientific truth, and of the impact that science continues to make in our lives. During your first two years we also require you to take at least four semesters of work in the social studies, which deal with man's relationship to his fellow men, so you may know what men have thought and are thinking in some of the areas of human decision that in our generation at the same time both threaten total extinction and promise a peacful world.

Beyond English 1-2 in the Humanities we make sure that you take at least two semesters of art, music, philosophy or literature, so that you may discover means of achieving a richer relationship with yourself. Another real purpose of your study of the humanities is to acquaint you with the role and scope of the emotions, and to lead you to make valid judgments of value and ethics as you confront fundamental questions. You must understand the place of value in a world of fact.

Then in your last two years you are required to have a major, which may possibly be pre-vocational. Don't feel that your major has to be particularly relevant to your future occupation. A man planning a business career does not have to major in Economics. Medical schools now recommend that pre-meds do not major in Chemistry and Zoology. Major in the subject you enjoy most, which interests you most, and consequently gives you the best chance to develop a trained mind that later you can use in any activity you choose. Whether it is vocational or not it will force you to explore in greater depth than you otherwise would one field of human experience. Moreover, a major will lead you far enough into a subject so that you are aware of your terrible ignorance concerning it, and consequently your even greater ignorance about the fields in which you have majored. In other words, we hope you will attain some of that wonderful quality called intellectual humility.

In addition to the major there are the free electives that enable you to follow any intellectual interest you may have in this curriculum of nearly 500 courses.

And finally, in your senior year you will all take a course in Great Issues, which attempts to relate your liberal arts education directly to the problems of adult living that you will face immediately after graduation - unless the Army, or Navy, or Air Force catches you first.

This is going to be your adventure in a liberal arts college. It is possible to have a liberal arts education that is so narrow in its selection of topics that it cannot be considered a liberal education. The curriculum under which we are now operating will, we hope, make such a narrowing at least difficult, if not impossible.

A liberal education may mean many things, but one is certainly that we try to educate the whole of you. If during your four years here you learn something about the major areas of human thought, the humanities, the social studies, and the sciences, exploring one of them in some depth; if you learn to express yourself clearly, precisely, and even gracefully; if you learn how to handle at least one foreign language; and above all if you learn to distinguish values so you can intuitively sense quality, then you are on the road to an education.

That is the rough outline. It is you who will fill in the details, and it is you who will live the experience. The liberal arts, as President Dickey has often said, are more properly called the liberating arts. They serve to make you aware of some of the critical issues and values in the experience of living, and start you off on a life-long search for understanding. As President Dickey pointed out in his Convocation address, when a man ceases to be a frontier to himself his education is at an end, and that comes when he no longer has hunger, hunger for the competence that will enable him to serve society and hunger for the conscience that will make him the decent human being he is content to live with and call on.

In the four years you are with us we shall make available to each of you the foundation for a liberal education, so that your lives will be the richer both for yourselves and for human society. With you, as with all our classes, our sights are high. But so are our hopes.

Honoring President Dickey on his tenth anniversary in office, more than one hundred1929 classmates presented him with a gun at a dinner at the Dartmouth Club, NewYork, Oct. 28. With him (l to r) are Jack Gunther '29, President Emeritus Hopkins,Bill Andres '29, class chairman, Phil Mayher '29, and Herb Ball '29, chairman of thecommittee that arranged the testimonial dinner.

DEAN JENSEN'S ARTICLE is based on the talk he gave to the freshman class, October 10, in the required first-semester course, The Individualand the College.

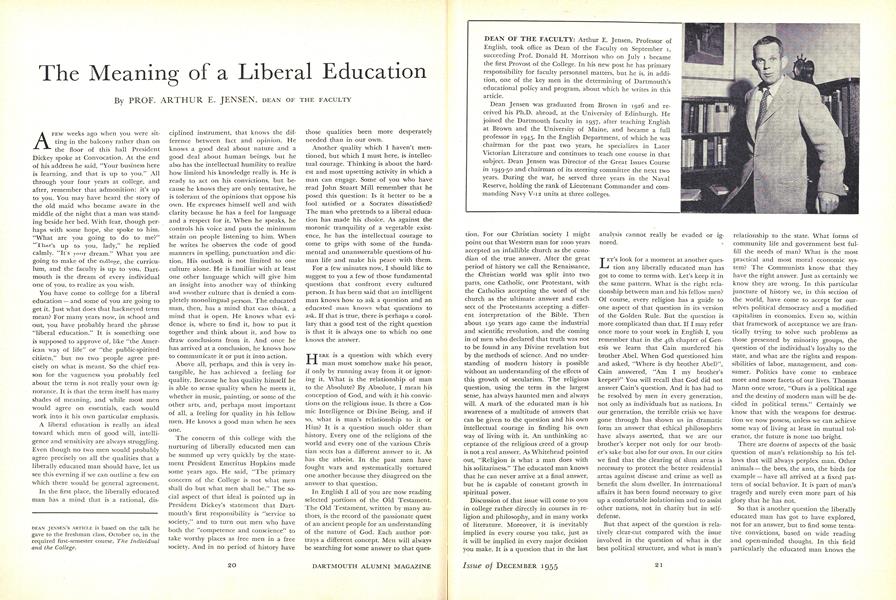

DEAN OF THE FACULTY: Arthur E. Jensen, Professor of English, took office as Dean of the Faculty on September 1, succeeding Prof. Donald H. Morrison who on July 1 became the first Provost of the College. In his new post he has primary responsibility for faculty personnel matters, but he is, in addition, one of the key men in the determining of Dartmouth's educational policy and program, about which he writes in this article. Dean Jensen was graduated from Brown in 1926 and received his Ph.D. abroad, at the University of Edinburgh. He joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1937, after teaching English at Brown and the University of Maine, and became a full professor in 1945. In the English Department, of which he was chairman for the past two years, he specializes in Later Victorian Literature and continues to teach one course in that subject. Dean Jensen was Director of the Great Issues Course in 1949-50 and chairman of its steering committee the next two years. During the war, he served three years in the Naval Reserve, holding the rank of Lieutenant Commander and commanding Navy V-12 units at three colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

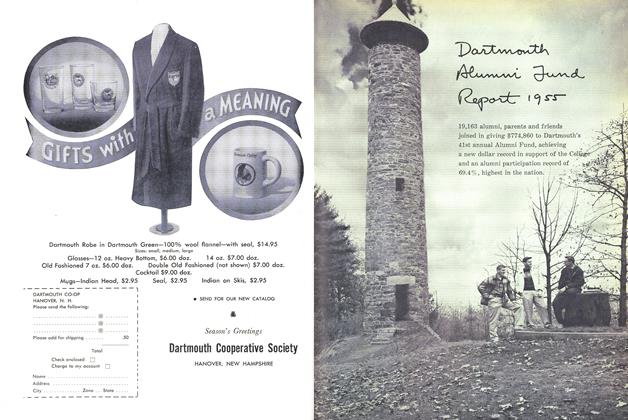

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21 -

Feature

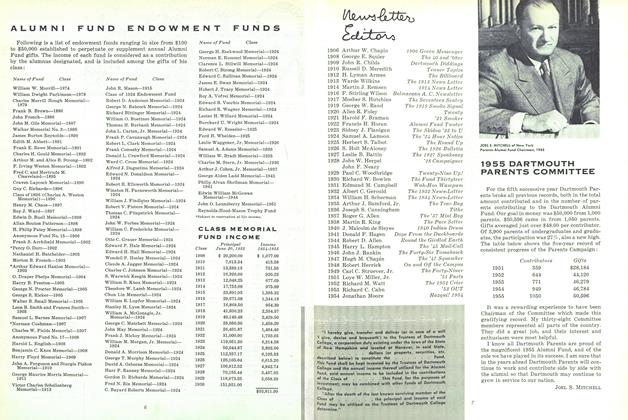

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

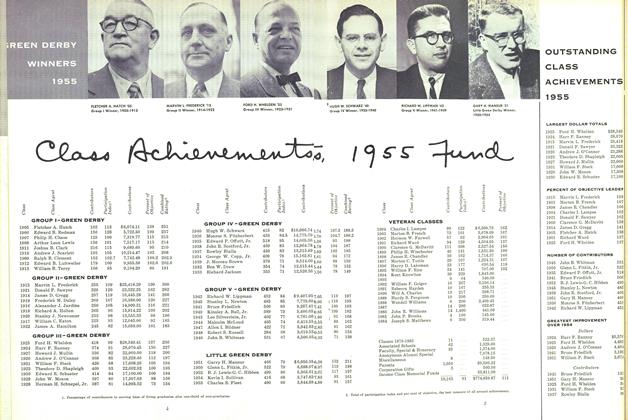

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

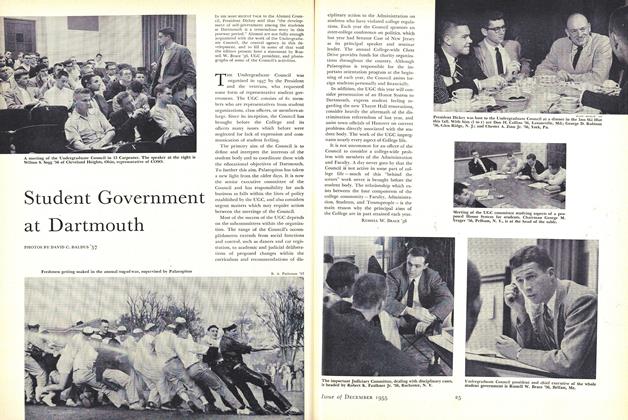

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56 -

Feature

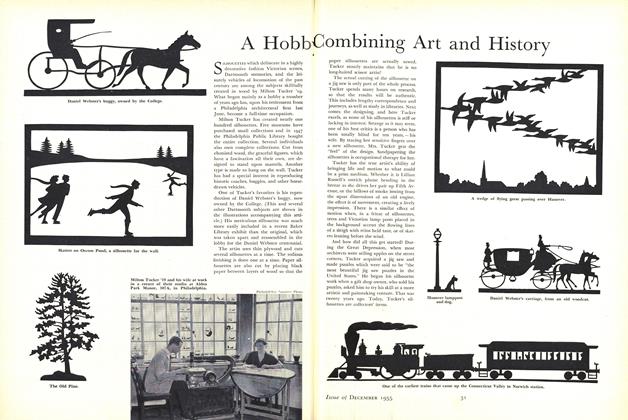

FeatureA Hobby Combining Art and History

December 1955

PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureTrade Unionist

MAY 1972 -

Feature

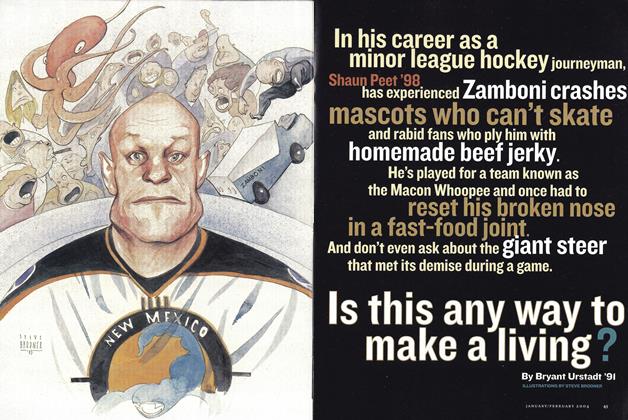

FeatureIs This Any Way to Make a Living?

Jan/Feb 2004 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

Feature

FeatureTo Screenwriting Born

November 1982 By Budd Schulberg '36 -

Feature

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

FEBRUARY 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

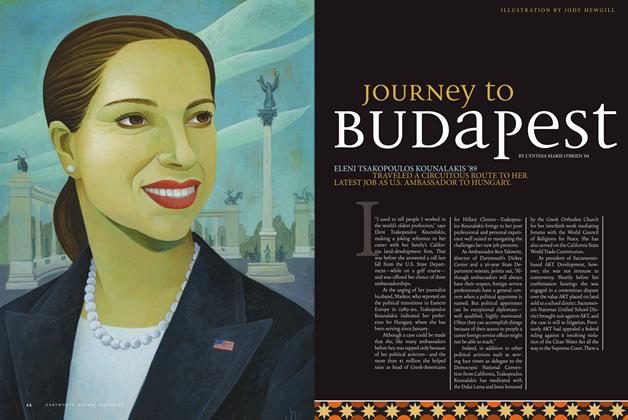

FeatureJourney to Budapest

Nov/Dec 2010 By CYNTHIA MARIE O'BRIEN ’04