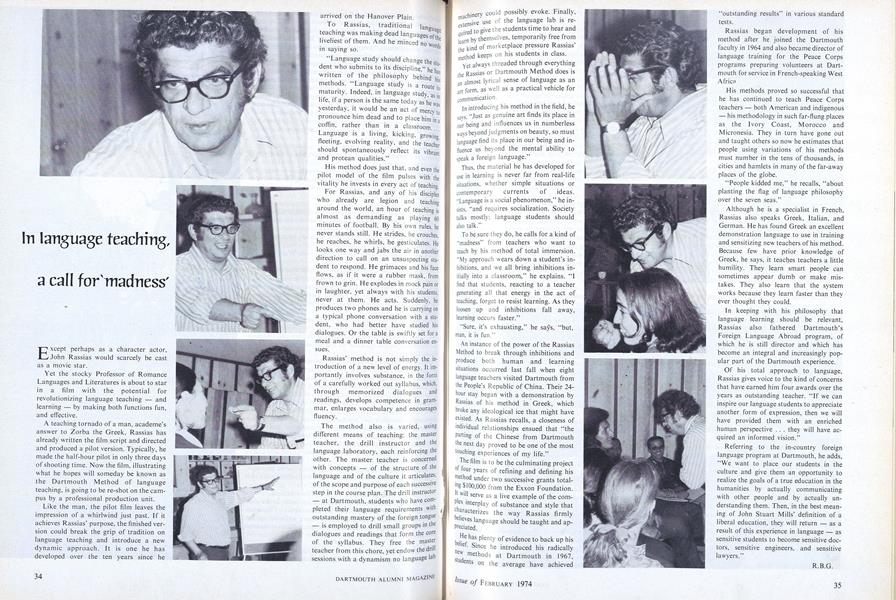

Except perhaps as a character actor, John Rassias would scarcely be cast as a movie star.

Yet the stocky Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures is about to star in a film with the potential for revolutionizing language teaching - and learning - by making both functions fun, and effective.

A teaching tornado of a man, academe's answer to Zorba the Greek. Rassias has already written the film script and directed and produced a pilot version. Typically, he made the half-hour pilot in only three days of shooting time. Now the film, illustrating what he hopes will someday be known as the Dartmouth Method of language teaching, is going to be re-shot on the campus by a professional production unit.

Like the man, the pilot film leaves the impression of a whirlwind just past. If it achieves Rassias' purpose, the finished version could break the grip of tradition on language teaching and introduce a new dynamic approach. It is one he has developed over the ten years since he arrived on the Hanover Plain.

To Rassias, traditional language teaching was making dead languages of the liveliest of them. And he minced no words in saying so.

"Language study should change the student who submits to its discipline," he has written of the philosophy behind his methods. "Language study is a route to maturity. Indeed, in language study, as in life, if a person is the same today as he was yesterday, it would be an act of mercy to pronounce him dead and to place him in a coffin, rather than in a classroom. ... Language is a living, kicking, growing, fleeting, evolving reality, and the teacher should spontaneously reflect its vibrant and protean qualities."

His method does just that, and even the pilot model of the film pulses with the vitality he invests in every act of teaching.

For Rassias, and any of his disciples who already are legion and teaching around the world, an hour of teaching is almost as demanding as playing 60 minutes of football. By his own rule's, he never stands still. He strides, he crouches, he reaches, he whirls, he gesticulates. He looks one way and jabs the air in another direction to call on an unsuspecting student to respond. He grimaces and his face flows, as if it were a rubber mask, from frown to grin. He explodes in mock pain or in laughter, yet always with his students, never at them. He acts. Suddenly, he produces two phones and he is carrying on a typical phone conversation with a student, who had better have studied his dialogues. Or the table is swiftly set for a meal and a dinner table conversation ensues.

Rassias' method is not simply the introduction of a new level of energy. It importantly involves substance, in the form of a carefully worked out syllabus, which, through memorized dialogues and readings, develops competence in grammar, enlarges vocabulary and encourages fluency.

The method also is varied, using different means of teaching: the master teacher, the drill instructor and the language laboratory, each reinforcing the other. The master teacher is concerned with concepts - of the structure of the language and of the culture it articulates, of the scope and purpose of each successive step in the course plan. The drill instructor - at Dartmouth, students who have completed their language requirements with outstanding mastery of the foreign tongue - is employed to drill small groups in the dialogues and readings that form the core of the syllabus. They free the master teacher from this chore, yet endow the drill sessions with a dynamism no language lab machinery could possibly evoke. Finally, extensive use of the language lab is required to give the students time to hear and learn by themselves, temporarily free from the kind of marketplace pressure Rassias' method keeps on his students in class.

Yet always threaded through everything the Rassias or Dartmouth Method does is an almost lyrical sense of language as an art form, as well as a practical vehicle for communication.

In introducing his method in the field, he says. "Just as genuine art finds its place in our being and influences us in numberless ways beyond judgments on beauty, so must language find its place in our being and influence us beyond the mental ability to speak a foreign language."

Thus, the material he has developed for use in learning is never far from real-life situations, whether simple situations or contemporary currents of ideas. "Language is a social phenomenon," he insists. "and requires socialization. Society talks mostly; language students should also talk."

To be sure they do, he calls for a kind of "madness" from teachers who want to teach by his method of total immersion. "My approach wears down a student's inhibitions, and we all bring inhibitions initially into a classroom," he explains. "I find that students, reacting to a teacher generating all that energy in the act of teaching, forget to resist learning. As they loosen up and inhibitions fall away, learning occurs faster."

"Sure, it's exhausting," he "but, man, it is fun."

An instance of the power of the Rassias Method to break through inhibitions and produce both human and learning situations occurred last fall when eight language teachers visited Dartmouth from the People's Republic of China. Their 24-hour stay began with a demonstration by Rassias of his method in Greek, which broke any ideological ice that might have existed. As Rassias recalls, a closeness of individual relationships ensued that "the parting of the Chinese from Dartmouth the next day proved to be one of the most touching experiences of my life."

The film is to be the culminating project of four years of refining and defining his method under two successive grants totaling $100,000 from the Exxon Foundation. It will serve as a live example of the complex interplay of substance and style that characterizes the way Rassias firmly believes language should be taught and appreciated.

He has plenty of evidence to back up his belief. Since he introduced his radically new methods at Dartmouth in 1967, students on the average have achieved "outstanding results" in various standard tests.

Rassias began development of his method after he joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1964 and also became director of language training for the Peace Corps programs preparing volunteers at Dartmouth for service in French-speaking West Africa

His methods proved so successful that he has continued to teach Peace Corps teachers - both American and indigenous - his methodology in such far-flung places as the Ivory Coast, Morocco and Micronesia. They in turn have gone out and taught others so now he estimates that people using variations of his methods must number in the tens of thousands, in cities and hamlets in many of the far-away places of the globe.

"People kidded me," he recalls, "about planting the flag of language philosophy over the seven seas."

Although he is a specialist in French, Rassias also speaks Greek, Italian, and German. He has found Greek an excellent demonstration language to use in training and sensitizing new teachers of his method. Because few have prior knowledge of Greek, he says, it teaches teachers a little humility. They learn smart people can sometimes appear dumb or make mistakes. They also learn that the system works because they learn faster than they ever thought they could.

In keeping with his philosophy that language learning should be relevant, Rassias also fathered Dartmouth's Foreign Language Abroad program, of which he is still director and which has become an integral and increasingly popular part of the Dartmouth experience.

Of his total approach to language, Rassias gives voice to the kind of concerns that have earned him four awards over the years as outstanding teacher. "If we can inspire our language students to appreciate another form of expression, then we will have provided them with an enriched human perspective ... they will have acquired an informed vision."

Referring to the in-country foreign language program at Dartmouth, he adds, "We want to place our students in the culture and give them an opportunity to realize the goals of a true education in the humanities by actually communicating with other people and by actually understanding them. Then, in the best meaning of John Stuart Mills' definition of a liberal education, they will return - as a result of this experience in language - as sensitive students to become sensitive doctors, sensitive engineers, and sensitive lawyers."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

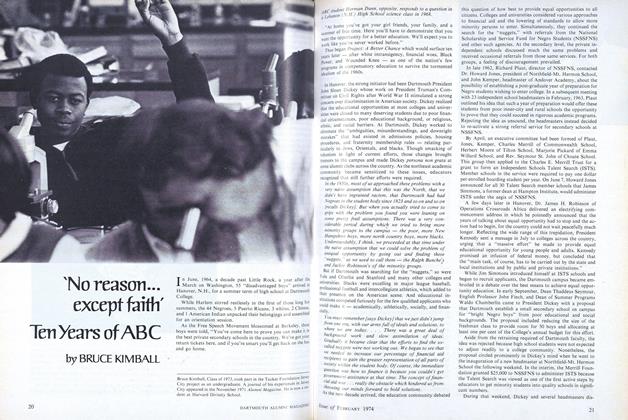

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Article

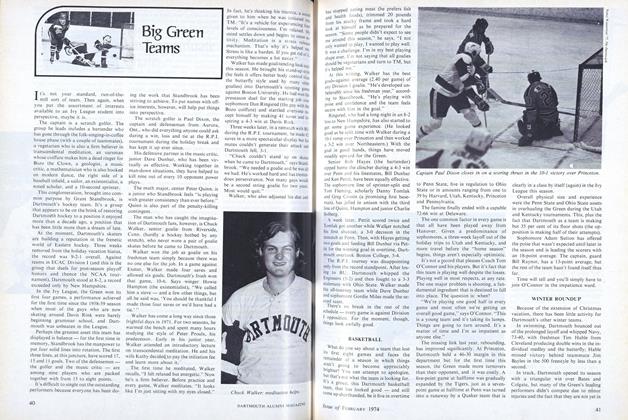

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

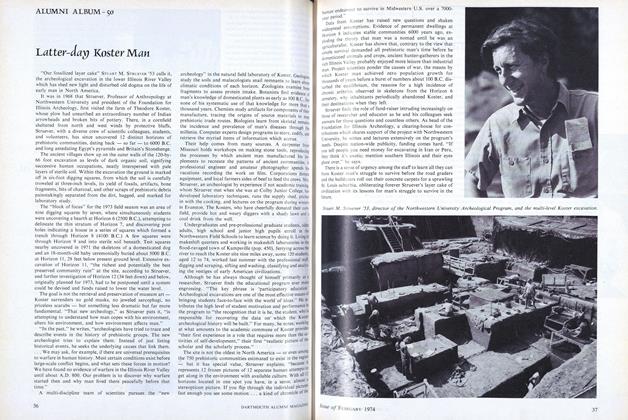

ArticleLatter-day Koster Man

February 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1974 By DREW NEWMAN ’74

R.B.G.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Parent Trap

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRIDE of a LIFETIME

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureEat Here

February 1992 By CHRIS WALKER '92 and TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Feature

FeatureRecommended Reading

Nov - Dec By GAVIN HUANG ’14 -

Feature

FeatureWelcome to the dark places

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureSETTING FREE THE MARKET

OCTOBER • 1987 By Tyler Bridges