I had the opportunity this summer to be an ambassador from another era at a 60th reunion of a Buffalo high school class. I watched the 13 classmates slowly file into a downtown men's club and look about for hints of familiar faces. They greeted old friends and pooled memories of an age when a nickel bought a street car ticket (and a transfer) and when young minds weren't troubled about their nation, their futures, and the attrition rate of carefully nurtured ideals.

What struck me immediately was how similar this gathering of old school friends was to the countless number of reunions and informal alumni rendezvous I have managed to attend at Dartmouth. There were the firm handshakes, the nervous surveillance of the others, the long pauses when memories are searched and events recalled.

But most startling of all was a curious feeling that filled the room. I had noticed it in nearly all of the green tents of the oldest reuning classes on those late spring days that are so beautiful it must hurt not to be young. But never before had I been able to identify it. Now, as the end of my undergraduate days are approaching - the College calendars even list the exact day of graduation, June 13 - I think I know what it is that seeps into those green tents. It is an absence of uncertainty.

A very dear friend of mine, now a school administrator, once counseled me to be wary of such alumni groups; he called them "liars clubs." Yet surely that feeling cannot be a lie. The litany of accomplishments, listed dutifully as if on an application for the Class of 1980, may be, as all things are in our times, inflated. But their memories contain a kernel of confidence that cannot be manufactured for their classmates' consumption. I wonder if we of this senior class will ever gather in dignified green tents filled with confidence.

Each generation, with the kind of perspective Copernicus should have eliminated, considers itself unique. Each seems to have a label, the social equivalents of the New Freedom, the New Deal, and the New Frontier. But we who were fourth graders when the New Frontier ended on a November afternoon in Dallas and junior high school students when Richard Nixon was first elected President are not as easy to classify.

We are not, of course, the Lost Generation: others have already claimed that epithet. And we surely cannot be, as The Wall Street Journal has suggested, the Second Lost Generation; we are, after all, the generation that took time off to find ourselves. Nor are we, however, the Found Generation, for we often feel that good and simple things - the small grocery store before the antiseptic supermarket moved to 'the shopping mall down the street, the lazy days at swimming holes before five- year-olds could pronounce a forbidding three-syllable word like "pollution" without difficulty, the presidency before it was imperial - have been lost.

So, I think, we are the Uncertain Generation. If we are certain about anything, it is of being uncertain. Unlike those reuning Buffalo high school classmates, we don't feel we confront a world of any stability. One 78-year-old man told me how secure he felt in the days before America entered World War I. "We had a feeling that nobody ever would - ever could - cross the Atlantic or the Pacific to bother us at home," he said. "We used armories for bicycle races and indoor track meets."

And my father, who lost a brother in the Pacific theater and who interrupted his Dartmouth education to serve during the Second World War, says he never felt the uncertainties he sees in my classmates and in me.

Of what are we uncertain? We believe, for example, in the fundamentals of a liberal arts education. Yet we know we face, at best, a crippled employment market at graduation. We would like to believe in America, but we see, even in these calmer post-Watergate days, much dishonor; this cannot be what Sam Adams had in mind. That a considerable number of federal employees recently refused to sign their names to the Declaration of Independence (it was, many said, awfully radical language) is an indication of how far we've gone.

So I look back on three years of a very intense and, I believe, a very fine education. Smudged between a summer I spent consumed with Watergate, a fall filled with football, and a winter when I felt as if I had rushed Baker, I remember more than one man's share of truly exhilarating college days. But still, I feel (and I see it in nearly all of my classmates) a certain uncertainty - and not about any one thing in particular.

We of the Class of 1976 have been reminded ad nauseum that, in addition to being the first coed class at Dartmouth, we graduate in the year of our nation's bicentennial and that our 25th reunion will be in the 2001.1 wonder how we'll view our uncertain times then. I think about these things, and I'm uncertain.

"We are not, of course, the Lost Generation.Nor are we the Found Generation ... for thegood and simple things have been lost."

David Shribman, a senior fromSwampscott, Massachusetts, has writtenfor Dartmouth's Office of Sports Information, The Boston Globe, The New York Times, and, as a staff reporter thissummer, for The Buffalo Evening News - "covering everything from Tiny Tim toGeorge McGovern." He will share theduties of undergraduate editor andWhitney Campbell 1925 Intern withDaniel Nelson, also a senior. TheCampbell Internship was established byRobert Borwell '25 to provide undergraduates with practical experience injournalism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

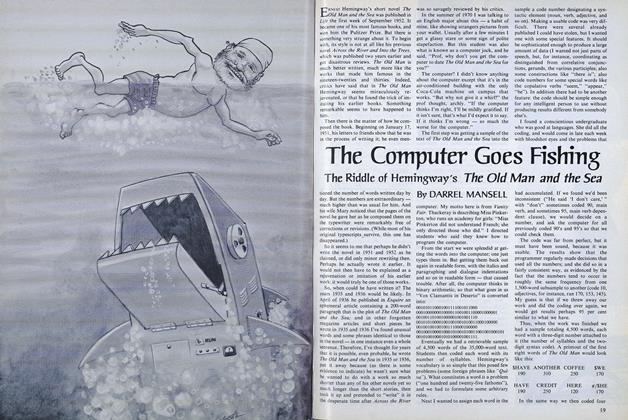

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

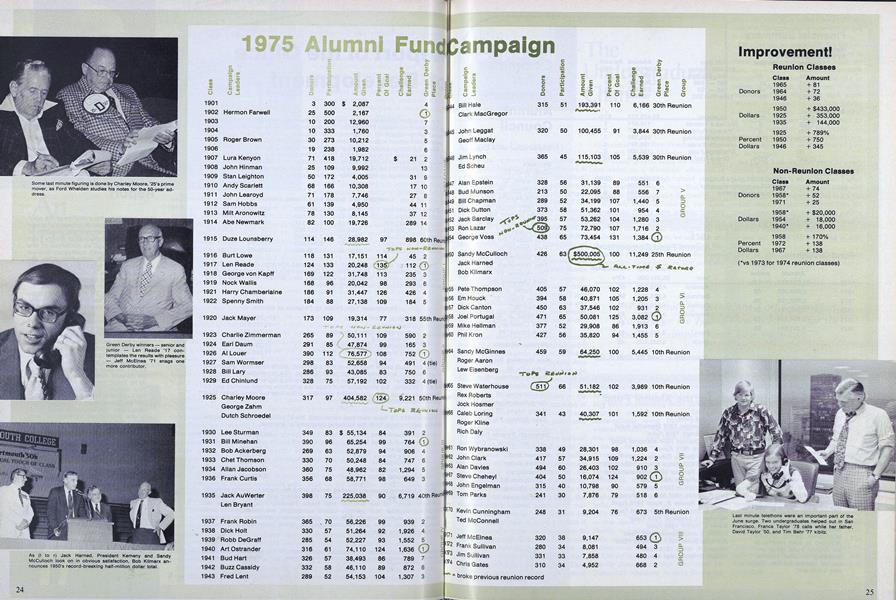

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975

DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76

-

Article

ArticleThe Silly Season

November 1975 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleA Son's Reflections

January 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksThis Sceptered Isle

December 1978 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksSoiled Pinstripes

October 1979 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Article

ArticleDark Horse of a Different Color

April 1980 By David M. Shribman '76

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

October, 1908 -

Article

ArticleQueen of the Snows Chosen

MARCH, 1928 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MARCH 1959 -

Article

ArticleMinimum standards: Beyond buildings to philanthropy

OCTOBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleGeorgia

JUNE 1969 By GLOWER W. JONES '58 -

Article

ArticleThe Constancy of Change, The Constancy of Devotion

July 1974 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24