In the early autumn of 1962, soon after the fall term at the College had begun, the new Hopkins Center was sufficiently complete so that it was possible to organize inspection tours of this new marvel on the campus. The guides were recruited from the faculty of the departments of art, drama, and music.

One day I found myself in charge of a group of alumni who were in Hanover, I recall, for the weekend football game. We began with the Center Theater, where the new seats were being installed and the floor was somewhat slippery because the carpeting had' not yet arrived, f asked the members of the group to sit in the seats, and I compared their comfort with the hard wooden seats of old Robinson Hall which we were finally leaving. At this point, one member of my group looked at me and said; “frills!” When I tried to explain that comfortable seats in a theater were hardly frills, he merely repeated the word. I moved on to the front of the stage where I knew I had a spectacular pitch in the three elevators for the forestage. I pointed out enthusiastically that they could be raised to stage height, lowered to floor level, and lowered still further to make an orchestra pit. There were exclamations of wonder and delight from most of the group, but not from my friend. He exploded with: “more frills!” Onstage, the depth of the stage, the cyclorama, and the electronic lighting system as well as the mechanical system for lowering and raising the scenery got appreciative murmurs from the rest of the group, but not from him. His reaction was succinct and direct: “Good God!”

At this point I sensed a real fury toward him building up among my group, but nothing was said. As we entered the scene shop to the left of the stage, where the sets were to be constructed and painted, I finally came to the new paint frame with its electric winch for raising and lowering. After years of painting settings on the Robinson Hall floor, here at last it was possible to nail the scenes to the frame and paint standing up. But my enthusiasm went for nothing as far as my friend was concerned. He now became very vocal. After repeating the word “frills,” he said that all this money spent on such things could be better used at the gymnasium. I finally turned to him and said: “You know, this type of paint frame was invented around the year 1450 A.D. Leonardo da Vinci had one, Michelangelo had one, and we're just getting around to it!” To my astonishment, the rest of the group broke into applause. My friend followed along the rest of the tour in complete silence.

At that time there were widely conflic- ting views about the wisdom of building the Hopkins Center, as well as grave doubts about its intended function in- cluding the expanded departments that it was to house. The word “frills” was not just the invention of my alumnus friend. Many faculty and townspeople held similar views. What most of the critics ap- parently did not realize was that all the elements to be incorporated in the new building had been present for years on the campus, tucked away in odd corners and almost hidden from view. The new building made it possible to pull all of these elements together and make them completely visible for the first time. Studio art courses were held on the second floor of a building acquired from the recently defunct Clark School. The Players oc- cupied the basement of Robinson Hall and either gave their productions two flights up or trekked their scenery over the way to Webster. The Music Department had of- fices in Bartlett Hall after years of oc- cupying the basement of Webster Hall. Most of those facilities were stop-gap solutions to the several departmental needs. Now finally, these activities were moving into a space actually designed for the three disciplines.

One unanswered question was: Would the students buy the concept and make effective use of the facilities? Even the so- called “student traps” the College post office and the snack bar would not automatically insure that the arts would draw that much interest. At the start some students saw through the aesthetic snares laid for them and complained about having to look at all that art every day! It was pointed out to these recalcitrants that there was a way of getting to both places without passing a gallery, or having to listen to music. The route was somewhat devious and inconvenient, but it could be done. Then suddenly, it was November and the building, thrown open to all, was func- tioning. Most of the criticism vanished along with the objections to the architec- ture, and as far as I am aware, it has never been revived.

Hopkins Center probably represents one of the major revolutions in the history of the College. In its inclusiveness, it brought the arts at Dartmouth out of hiding. It drew together all the diverse strands of ar- tistic endeavor and provided them a worthy setting. The Players had indeed done shows of excellent quality in Robin- son and Webster, and the loyal audiences that sat on hard seats in both halls were candidates for martyrdom. The Glee Club and the band gave periodic concerts in Webster, but they were never seen at other times since all rehearsals took place on the second floor of Bartlett Hall. The Clark School, which housed the studio art classes, was completely invisible except to those whose urge toward painting or sculp- ture was strong enough to warrant the search.

This new visibility in the arts was almost immediately reflected in the curricular changes that accompanied the opening of the center. The Art Department brought new and exciting courses to the new building. The Drama Department then still allied with English produced a whole new curriculum in theater, befitting its new teaching facilities. The Music Department did not change as im- mediately or as dramatically, but over the years the building has stimulated ex- periments later confirmed in the curriculum. None of this upsurge in the arts would have been possible without the Hopkins Center.

Important as the center was in curricular development, the combination of other elements within the structure probably did more than anything else to win the acceptance of the students popula- tion and the wider community. Easy access to the art galleries, in contrast to the third floor of Carpenter Hall, quadrupled the number of viewers. New equipment for working in both wood and metal in the lower-corridor workshops meant increased participation. The two second-floor lounges provided a gracious, relaxing at- mosphere for students and community guests alike. Certainly, the wisdom of throwing all these diverse arts together has proved most successful.

It should be noted that it was the fact of the center which gave birth to the most revolutionary one is almost tempted to say non-Dartmouth discipline: the dance! Even in 1962, few would have predicted that the dance would ever become accepted. I personally bear scars in this regard. Early in the thirties, the directorate of the Dartmouth Players decided that if dance could be a part of the training, it would help actors to move on the stage with greater ease and agility. I happened to be the one selected to inquire of the powers at the gymnasium whether a dance course qualifying for the general credit in “recreation” could be instituted. When I broached the subject I was literally hooted out of the gym. Now, of course, it is not unusual for football coaches to prescribe dance for their players for precisely the same reason the Players urged it years ago. It is also no secret that out of this set of dance courses came the Pilobolus troupe which has grown to inter- national fame.

Unlike most other disciplines in the College, the arts always involve practice and performance, the “doing” of an art itself part of an educational learning process. The difference from other lear- ning processes lies in the fact that the do- ing and practice must be shared with a wider group known as the audience, which in turn participates as an integral and in- dispensible part of the whole process. Yet until the Hopkins Center came into being, much of the opportunity to practice was muted by the low profile of the arts on campus, not to mention the inadequate ■quarters. Nevertheless, the indispensible need of an audience was recognized many I years ago, and every effort was made in the old days to increase the number of times a play or a concert was repeated. In Robin- son Hall a play was normally given three or four performances. In the center a play ordinarily runs for approximately eight or ten performances and the number has risen at times to 14 or 15.

This opportunity to perform may well account for the increasing number of re- cent graduates in the arts who continue on professionally. For last month’s 15th an- niversary of the Hopkins Center, some 70 former drama students who have graduated since the building was opened were invited back to celebrate. While 40 of them made the trip and at some con- siderable inconvenience, the remaining 30 were unable to come owing to com- mitments in the theater. This is an amaz- ing record for an undergraduate college. Some had, of course, gone on to graduate school for further training, but many had gone directly into some sort of professional theater work.

For many years Dartmouth has had a good many older alumni who have dis- tinguished themselves in the theater, but rarely in such numbers. Here again, the reason must lie with the center, which per- mits far more activity than before and af- fords an interested student the opportunity to practice his art before an audience, in the long run his best teacher. He can ex- periment, make mistakes where the resulting scars and disappointments are never permanent or fatal. This self- imposed training gives him courage later to face the professional world with reasonable confidence.

Much has been said about the audience, and more could be said, for it is the real crown of the center’s activity. Audiences are not easily acquired, yet over the last 15 years they have been nurtured and fostered. As they grew, it became evident that they were also growing in sophistica- tion. The effect on the departments of art, drama, and music was to force them to constantly higher standards of perfor- mance, even to some curricular changes. The introduction of visiting artists almost unheard of before 1962 as well as wider selection of .concert offerings by visiting groups, has also had an effect on both audience and student.

Perhaps the most salient reason for building an audience is the realization that Dartmouth College is happy to share its artistic ventures. Professionals and amateurs participating in offerings of the center are accepted with equal enjoyment and a kind of deep understanding on the part of the audience. It should be explained that the standards for student work are generally higher and some student work is excellent indeed. I hasten to add that stu- dent standards and aspirations have always been high, but the opportunity to realize them sometimes fell short of the mark, for lack of facilities of a frame to set them off.

Several years ago, two Dartmouth alumni of the late thirties, both formerly active in the Players, came in to watch a final dress rehearsal of the Carnival play. They sat in silence until, at the end, one turned to the director and said: “We were never that good!” Actually they were quite as good in their day, considering the facili- ties they had. They merely lacked the Hopkins Center frame.

If the frame that is Hopkins Center does nothing else but foster excellence, it will have done its work well. That it has already done its work is evident in the changing attitudes of the College toward the arts. Its glorious by-product has been to strengthen the education of the wholeman, which was the ideal of the man whose name the center bears.

Mark Abramson Overleaf: for community and college alike,Hopkins Center has been a revolutionizinginfluence. Last Christmas, when thisphotograph was taken, several thousandschool children attended daytime perfor-mances of “The Wizard of Oz.’’ Adultsand Dartmouth students have responded inkind to offerings in drama, music, art.

Henry B. Williams is professor of Englishand drama, emeritus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

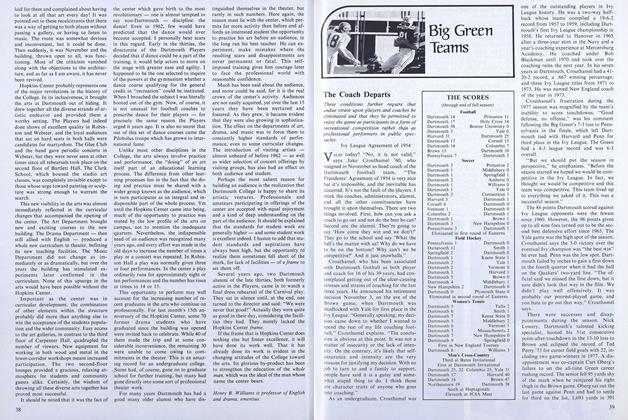

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

December | January 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

Henry B. Williams

-

Article

ArticleA Players' Report

June 1947 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE STAGE MANAGER'S HANDBOOK.

January 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

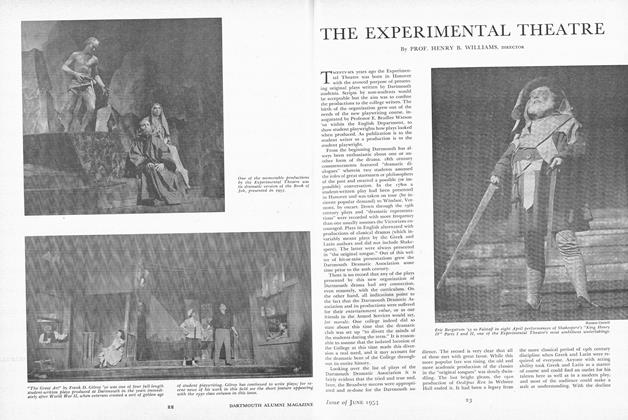

FeatureTHE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

June 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksSHAW AND THE 19TH CENTURY THEATRE.

NOVEMBER 1963 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE LONDON STAGE 1600-1800, PART 4, 1747-1776.

JULY 1964 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHEATRES AND AUDITORIUMS

JUNE 1965 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

JUNE 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH CUP

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

Featureclass notes

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 -

Feature

FeatureTwo Questions About Getting Into College

April 1961 By FRANK H. BOWLES -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureLANGUAGE LABORATORY

DECEMBER 1958 By PAUL R. OLSON, INSTRUCTOR