NOBODY has ever called me "nice." Still, "what's a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?" is something I've asked myself often. Whether in KÖln, Germany (where, stranded in the train station, I spent a Felliniesque night in the company of lechers, beggars, and whlores), in Provincetown, Massachusetts (Where, having lamely stumbled into an all-male gay bar, I nearly won the prize for most convincing drag queen until the judges discerned I wasn't wearing a costume), or even at dear old Dartmouth (where, particularly during that first difficult year of coeducation, slumber was frequently interrupted by those who chose to shout obscenites about "cohogs" underneath my dorm window), the ponderous question has cropped up time and time again.

Never, however, has it nagged at me quite so relentlessly as during a recent trip from Denver to New Hampshire. Trundling along during those wee hours of the morning when the iridescent "70" on the Interstate shields signifies both the route taken and the general speed of the traffic, my beat-up compact was consistently outnumbered, outsized, and outdistanced by a ceaseless and serpentine procession of big rigs. Similarly, in the numerous truckstops where I stared into "bottomless mug" after "bottomless mug" of rank coffee, I usually found myself - a solitary young woman surrounded by counters lined with burly men - equally out of place.

Just what a nice girl like me was doing traipsing around truckstops at all hours of the night is, on the surface anyway, easy to explain. Unable to find a cross-country companion, save one, who (for reasons I never fully understood) was incapable of handling a stickshift, I was pressed to find a way to break the trip's solitary monotony - a monotony that promised to be especially tiresome due to my car's lack of even an AM radio and the fact that my schedule would permit only one overnight sleep stop. Neither talking to myself nor conjugating French verbs seemed likely to keep me alert, much less entertained, for the entire 2,000 miles. So, knowing that journalism is a justification for almost any insanity, I purchased the requisite reporter's notebook and left Denver intent on investigating every truckstop passed along the way. My mission was to gather material for an article on truckstop cuisine, which I had mentally set in New Yorker type and tentatively titled "Heartburn Across America's Heartland."

From the safe distance of the Mile High City it had seemed like a great idea, but it didn't look so hot on the dusty outskirts of Salina, Kansas. And by the time I scurried past the St. Louis Arch I had soured on the idea of writing on truckstop food altogether. This wasn't because truckstop fare proved uninspiring; to the contrary, the literary possibilities of such items as "sausage gravy" (a polite euphemism for a midwestern delicacy that anywhere else would be called pan drippings) and "The Road Buster" (a hefty hamburger concoction that bears the apt warning, "You may need an overload permit for this one") seemed inexhaustible. No, it wasn't the limitations of the grease-laden cuisine that caused me to ditch my plans, it was the creeping realization that focusing solely on truckstop food would be like going to the movies primarily to eat popcorn. Even in shadowy fluorescent light, it's clear that there's much more to a truckstop than food.

To the average motorist, a truckstop's finer points are not glaringly obvious. With the exception of the garish Stuckeys, each of which sports a HoJo blue roof shaped like a misguided cross between a pavilion and a pagoda, most are bland, boxy structures that offer little respite from the characteristically dull Interstate scenery. Call them aesthetic monstrosities, testaments to 20th-century tackiness or just plain eyesores, most truckstops, from the exterior anyway, aren't exactly the ultimate in roadside attractions.

Inside, the scene is something else again. While true to their outward appearance in the sense that most are full of junk, the array is so colorful and extensive as to create an environment that's anything but dull. Part service station, part hostel, part hang-out, but mostly K-Mart, the modern truckstop is crammed with enough conveniences and consumer goods to satisfy efficiency expert and impulse buyer alike. Lockers, dorm rooms, truck-washing facilities, psychedelic juke boxes stocked with country tunes, corral-like boutiques full of Stetsons, sharp-toed cowboy boots and "White Truck" belt buckles - you name it, the truckstop's got it. From toothpaste and prophylactics to less essential trinkets like stenciled keychains bearing the name "Butch" to flashy new L-model Macks, which start at a mere 35 grand, everything the traveler could want - and more - is right there beside the highway. And some truckstops, like the Truckstops of America in Brookville, Pennsylvania, surpass even the most grandiose of expectations by offering, of all things, a bank branch, a barbershop, a post office, and a resident chiropractor.

Appreciated as all these amenities doubtless are, they're really beside the point, for what brings a trucker to a truckstop is not always as tangible as a penchant for knick-knacks or a pulled sacroiliac. To be certain, necessity is a factor motivating many truckers, who need to stole up on coffee at least as often as their 200-gallon diesel tanks require topping off. But what really causes a trucker to stop is other truckers, because a main function of a truckstop is to provide an arena for interaction of an almost familial sort, to impart a sense of community to - who have sacrificed roots for the noble cause of ensuring that the lettuce in urban; supermarkets be fresh. Though more like cogs in the ever-churning wheels of American commerce than kings of the road, truckers, many of whom have no other home to claim as a castle, rule in truckstops - and they do with a "don't tread on me" machismo.

FOR all but the most sure-footed, trespassing on trucker turf as a lone female can be an intimidating experience. But I, while not so foolish as to expect to be able to invade an all-male enclave and fit right in, figured I could pull off a truckstop entrance with at least a feigned air of nonchalance. After four years of fraternizing, wasn't I a pro at pretending to feel at home in places where women were obviously, sometimes vociferously, resented? Wasn't a truckstop in the middle of the night precisely the sort of situation Dartmouth had prepared me for?

Not quite. To be sure, entering a truckstop alone was somewhat reminiscent of walking into a fraternity house unescorted and uninvited. Only it was worse, much worse. Though truckers wear their GMC caps and tattoos in much the same way that fraternity brothers flaunt letters of the Greek alphabet and Izod alligators, the similarities between the two don't extend far beyond the back-slapping, cussing camaraderie. The crucial difference is that the Brotherhood of Teamsters is not a social club for future bankers, lawyers, and others prepping for guaranteed entry into the old-boy network. It's a formidable, even fearsome, union whose members are not merely men, but men of the working class. And at Dartmouth, where class usually means either a room in a brick building or the two digits tacked onto your name, I may have learned to act like one of the guys but I didn't learn much about mingling with those outside my own privileged milieu.

My first attempts at mingling with truckers were feeble ones, usually meeting with obscene gestures, hostile silence, grunts, a hand on the knee or a less subtle advance. Still, I persisted with my efforts at conversation because there was little else to do. As much as I wanted to crawl into the woodwork, the preponderance of formica and vinyl precluded that option. And as easy as it was to hide behind truckstop menus, there's a limit to how many colloquial descriptions of hamburgers you can read without getting bored.

For one whose entire previous knowledge of truckers derived from a single episode of Movin' On and that annoying song "Convoy," conversations with truck drivers were an education well worth the effort. Eyes wide, I listened attentively to bizarre tales of truck hijackings, gang murders, police vendettas, monstrous accidents, and back road romance. I picked up some trucker lingo (a "KW" is a Kenworth cab; a "lie sheet" the trucker's daily log); acquainted myself with individual trucker's attitudes about everything from automobile use of CBs ("the 'civilians' are ruining a good thing" - "it makes me madder 'n hell to see a four wheeler with four antennas") to the quality of truckstops ("they're going downhill because the big corporations are buying the little guys out") to the Interstate Commerce Commission ("the ICC is absurd"); and found out what truckers think of their media glorification ("it's off the mark: life on the road ain't one big convoy"). Some curious matters were only partially demystified: When I asked how one changes a huge hundred-pound truck tire, the reply was simply, "With great difficulty."

ONE trucker with whom I had little difficulty talking was Daniel. We met midway through my trip at the Effingham Truck Plaza in Effingham, Illinois, at which point I was feeling particularly tired and lonely. Despite pleasant conversations with truckers at previous stops, the distance was still great; halfway home I was well aware that asking questions of truckers had not made me any less an outsider, just more a voyeur. So when Daniel turned the tables by initiating a genuinely friendly conversation with no prompting on my part, his words were a welcome surprise.

At first, I was a bit wary about my new friend's intentions. Wearing an open-collared cotton shirt, neatly pressed flared jeans and cowboy boots, and sporting a silver filigreed lighter that he handled as swiftly and adeptly as a gunslinger a six-shooter, Daniel was simply too smooth to be beyond suspicion. Nonetheless, he was gregarious without being overbearing, articulate yet unaffected, and engagingly funny. Besides, he was going my way.

After ending our first meeting with a tussle over the check that was totally disproportionate to the 80 cents at stake, Daniel and I arranged to meet at several truckstops along Interstates 70, 71, and 80. In between stops, he and his fellow truckers kept a protective watch over me, so protective as to border on the suffocating; after getting off the road once in order to seek out a rest room I was greeted at the next truckstop with an accusatory "Why'd you get off at exit 20?" For the most part, though, I did the inquiring. And over many cups of coffee, Daniel shared the insights and experiences of ten years' trucking with the same speed and straightforwardness that gets him from Indianapolis to New York and back again thrice weekly.

With painstaking attention to detail, he covered topic after topic, reviewing the myriad rules and regulations imposed on truckers by the Interstate Commerce Commission, tracing the history of trucking from its independent or "wildcat" beginnings to its eventual conglomeration into corporate fleets, and showing me that filling out a "lie sheet" involves a ruler, a protractor, a fertile imagination, and a total disregard for either the Ninth Commandment or federal law. He gave me a crash course in weight-watcher psychology, explaining that some weigh-station operators, hoping to trap truckers, will wait until a caravan of unsuspecting drivers approaches before suddenly switching the scales sign to "open." When this happens, said Daniel, trucks will back down the highway en masse rather than be fined by a sneaky weight-watcher.

To my amusement, Daniel also described the scene at the Dayton, Ohio, truckstop that is infamous for its hordes of cab-hopping prostitutes "who are so thick in number that you could knock 'em down with your rig like bowling pins," but whose wares Daniel has never sampled because he has "no intention of ever getting venereal disease." In this personal vein, Daniel was free with advice, alternating between cautioning me against marrying a trucker and telling me to "be cool." When I told him I had no plans to marry anyone, he commented, "That's cool."

My own feelings towards Daniel were often uncool, turning from hot to cold as my elation at finding a truckstop companion alternated with fatigue-induced paranoia. Not having slept since Kansas City, I was riding up and down on an emotional roller coaster by the time we reached Pennsylvania's hilly Route 80. Each prearranged rendezvous was preceded by lurid hallucinations of the horrible fate that was sure to befall me, and I approached each truckstop uncertain as to whether I'd actually stop and go in to meet him. A lifetime of being told not to talk to strangers, to lock my car doors, to pin my money inside my bra, to stay out of unlit parking lots, and to avoid the unknown, especially when embodied by an older and attractive man, was obviously taking its toll. I even - no kidding - began to worry about how my mortified mother would react when the police discovered her daughter's mutilated body clad in faded and torn underwear.

But I always overcame my fears of playing the fly to his spider at the last minute and never stood Daniel up. In fact, exhaustion overtaking me like a jacked-up Chevy in the left lane and leaving me without a shred of common sense, I became so bold as to accept his invitation to see the interior of his cab. There, rather than attack me at gunpoint (Daniel, like many truckers carrying expensive cargo, "packs heat"), he offered to give me driving lessons.

The sessions spent learning to operate his KW's numerous gears in the lots behind truckstops were, of course, the source of much lewd speculation among Daniel's trucker buddies, who leered knowingly as we walked out back. By the time I had mastered the hissing brakes, every trucker within CBing distance had assigned us appropriate roles in a high speed melodrama: Daniel, the rake; me, to use the printable term, the pickup. "They'll be talking about us for months," said Daniel. To give them plenty to talk about we played along, hamming up each truckstop scene by holding hands, whispering earnestly, and giggling with mock intimacy.

Letting his compatriots' imaginations roam, Daniel and I traveled in tandem for about 600 miles, finally diverging just east of the Buckhorn Truck Plaza in northeastern Pennsylvania. As he flashed his lights in a farewell salute and I shifted into fourth, I realized that although I still had several hours to go before reaching my New Hampshire bed, the significant part of my journey was over. No matter how many mere miles I might travel, I knew that short of flying to the land of Islam, I'd rarely again get farther from the world to which I'm accustomed than a midwestern truckstop in the middle of the night.

As much as I would have been willing to trade my by-now massive collection of pilfered truckstop menus for another chance to sip coffee at a Union/76 or Skelly Cafe, the remaining hours of the journey were pleasant, for before we parted Daniel told me something that kept me chuckling the rest of the way home. It turned out that his motivation for approaching me way back in Effingham, Illinois, was not the ignoble one I originally suspected, but a matter of gallantry. After watching me (dazedly oblivious to the sign overhead, a sign only the most hare-brained would fail to heed) sit down in a "truckers only" section, Daniel had decided I was in need of a rescue. "When I saw you walk right in and set yourself down smack in the middle of trucker territory, I wondered what the hell you thought you were doing," he said. "You know, for someone who went to a fancy college it was a real dumb thing to do."

With the brotherhood, unescorted and uninvited

Mary Ellen Donovan '76 is a writer wholives in Lyme Center, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

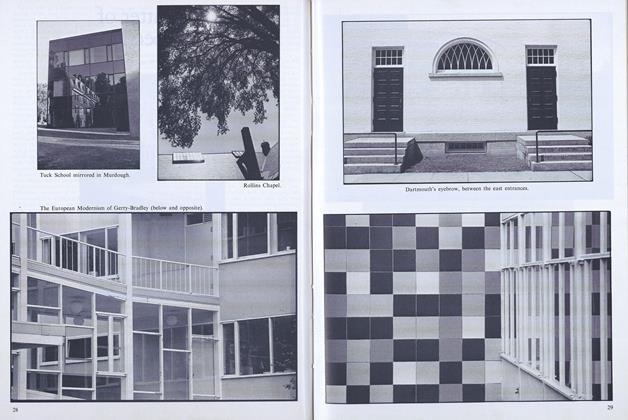

FeatureBeauty and the Beasts

October 1978 By William Morgan -

Feature

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

FeatureA Matter of Perspective

October 1978 -

Article

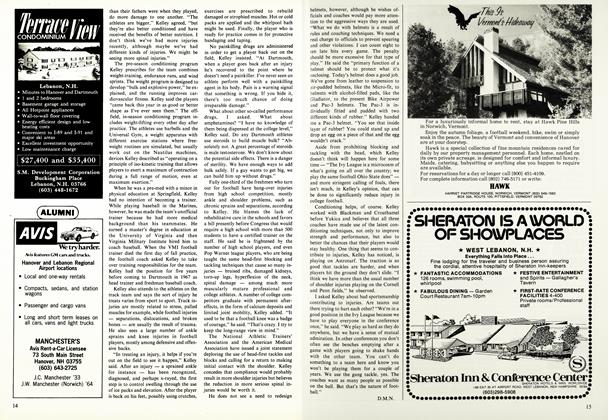

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

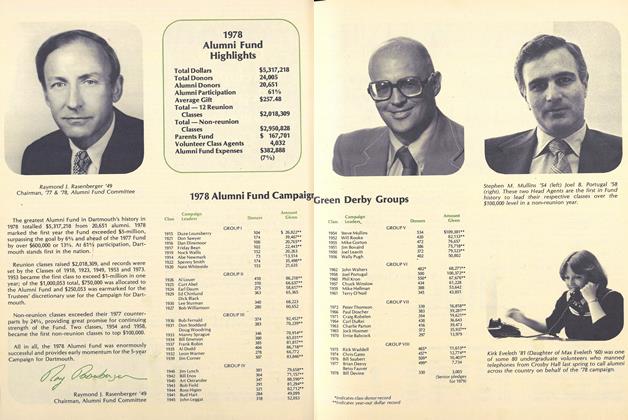

ArticleOffice of Development Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R.

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLandauer Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1964 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

December 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryEDWARD TUCK’S POCKET WATCH

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

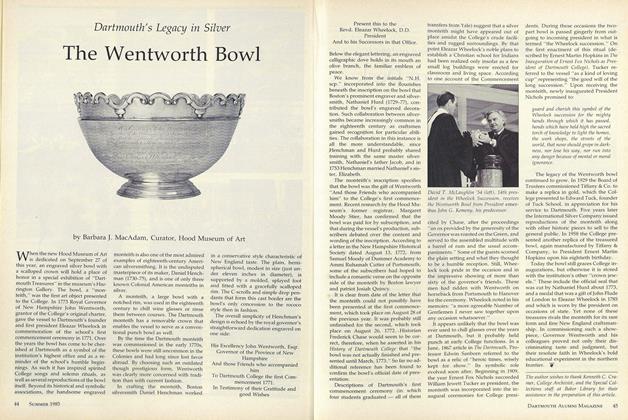

FeatureThe Wentworth Bowl

June • 1985 By Barbara J. MacAdam, Curator, Hood Museum of Art -

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May/June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

Feature

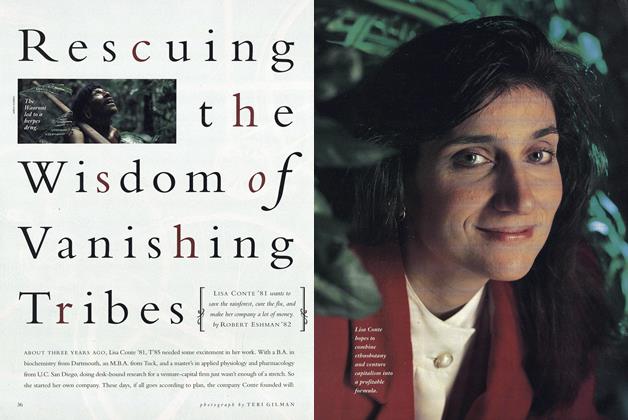

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82