TRANSKEI'S HALF LOAF:

Race Separatism in South Africa

Newell M. Stultz '55

Yale University Press, 1979. 183 pp. $16

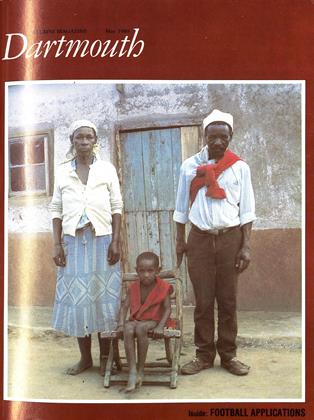

Stultz has written a serious book on the "independence" of Transkei a subject most people do not take seriously. On October 26, 1979, the Republic of South Africa ceded legal sovereignty to Transkei, previously a black homeland, or Bantustan, within the Republic. The same day the U.N. General Assembly (by a vote of 130 to 0 with the U.S. abstaining) denounced South Africa's action as a fraudulent means to hide continued white political control and economic dominance. Yet, as Stultz observes, something has certainly changed. Anyone who wishes to enter Transkei must get permission from its officials and obey its laws. Furthermore, Transkei has enfranchised blacks (though the conduct of its elections does not appear to have been notably democratic) and abolished the laws of apartheid.

What, however, do these changes mean? The central issue posed in this book is whether South Africa's policy of providing legal sovereignty to its homelands amounts to a first step toward either increasing racial justice or reducing racial tensions in South Africa. As a self-proclaimed conservative on these matters, Stultz offers as sympathetic and as informed an investigation of these issues as South Africa is likely to get from any nonpartisan outsider. For this reason his conclusion that Transkei is largely irrelevant to the resolution of these problems amounts to a far more devastating critique of South African policy than could any radical condemnation of the regime.

The major source of racial tensions in South Africa concerns the grievances held by urban blacks who are essential to the production of wealth that largely benefits whites and who are more conscious than blacks living in rural areas of the fundamental unfairness that the application of doctrines of racial separation has created. Making Transkei independent had startling consequences for urban blacks whose first language was Xhosa. They amount to onethird of Transkei's new citizens. Even if they were born outside the borders of Transkei and never intended to return, no matter what their personal desires might have been, they lost their South African citizenship. Since they have no interest in the largely rural and poor state, the effect of changing their citizenship is to weaken their claims to better treatment in the areas in which they live. Furthermore, the disjunction between the preference of one-third of the "citizens" of the new state and the legal identity imposed upon them reduces the seriousness with which Transkei's sovereignty can be taken.

In addition to these points, Stultz also gives a useful description of political events during the first year of "independence" and a sketch of Kaiser Matanzima, the prime minister. In a depressing number of ways, political behavior in Transkei resembles that in many other African states. There is a poorly organized dominant party, one-man rule, enrichment of a small elite, and heavy political and economic dependence upon a powerful and wealthy in- dustrialized state. Perhaps the limits to Transkei's claim to sovereignty tell us something about the limits of independence elsewhere in Africa.

Nelson Kasfir is associate professor of government at Dartmouth and a specialist on Africanpolitics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

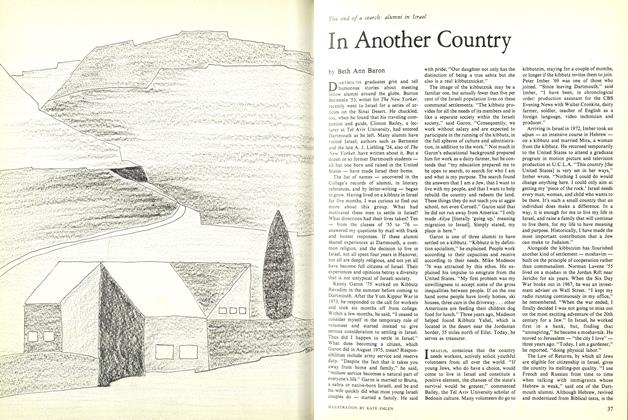

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE LIFE AND WRITINGS OF JOHN BUNYAN

FEBRUARY 1929 By A. W. Vernon -

Books

BooksNo-Fault: Try It, You'll Like It

October 1975 By CARYP. CLARK '62 -

Books

BooksTHE INTERNATIONAL COURT

October 1932 By D. L. S. -

Books

BooksCUENTOS DE MAGON.

APRIL 1970 By FLORENCE L. YUDIN -

Books

BooksREVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE: AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FORCES UNDERLYING THE TRANSITION FROM ROYAL PROVINCE TO AMERICAN COMMONWEALTH

October 1936 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksTHE HUMANITIES TODAY.

MAY 1970 By NEIL OXENHANDLER