It's a dance, it's whimsy, it's an 'up,' it's

How come such a radical change inlifestyle?

Do I know why? Only partially. The deeper layers of awareness still elude me.

For years something was building up inside like a slow rolling snowball. I can only identify that "something" as a diffuse sense of dissatisfaction in spite of a good job, a bright future, generous material surroundings, bucks in the bank, and all those good things. An inner voice kept nagging me: "Is this living? Do you feel good? Is this it?"

My heart knew the answer. No, God, no.

Everything seemed smooth and glossy on the surface, but the inside felt gray and soggy. My marriage had exhausted itself. My job was demanding but by no means fulfilling. Free time was relatively scarce and too much of it occupied with domestic chores and rituals doing the social niceties. Yes, I was ecstatic when flying my gorgeous, fully instrumented Cessna-180. On the whole I was living in a self-concocted mechanical maze. From the alarm in the a.m. to the click of the light switch in the p.m., it was prescribed.

It was routine. It was deadly. And what was worse, I knew it. That haunting inner voice kept at me: "Where do you exist? Where do you exist? How does it feel? How does it feel?

At the place in Northport, out on Long Island, there was a separate structure housing a sauna unit. One mild spring evening after a sauna bath, I wandered back to the main house. The lights were on in the orchard. There was the soft fragrance of apple blossoms in the air. The Chrysler convertible (top down) was in the driveway. The pink dogwood in front of the house was in full bloom. A lovely scene. It all seemed so perfect. I had it made. Yet I also saw it as a mere stage set. Things in juxtaposition. Props. Pretty props . . . empty and meaningless.

I was 50, settled-in and solidly trapped. There was a surging inside of me: I've got to feel alive . . . my remaining years are probably not that many . . . before it's too late I must fulfill my life . . . it's got to be my life for once, whatever that may mean and whatever the price.

How do you pull that one off?

I took a clue from Confucius. He said, "The shortest way out is through the front door." I believe that to be true. It really takes just that. If there's any wobbling, forget it.

Actually, I did a number of things in preparation. I spent a couple of years in therapy to find out what was going on within me and in particular how to avoid repeating old life patterns. I moved out of the house in Northport and lived at my apartment in N.Y.C. for a year before Ddvy (departure day). I was seeing a lot of young people, ladies indulging, exploring, involving myself in encounter groups, and gradually closing out my old life as best I could, leaving no loose ends.

In anticipation of D-day, I was often torn apart by pain and a sinking sense of despair. My daughter was still young, and the possible effects on her disturbed me deeply. My wife, too, would have to make wrenching adjustments. From a certain viewpoint I was about to make a ruthless decision. At times it seemed all too much. I broke down the mission into workable pieces. The pact with myself was simply to cross the Hudson River. Nothing more. Over the remaining months, I cleaned up my responsibilities at the office, arranged for a leave of absence, let the lease lapse on my N.Y. apartment, sold the plane, paid the bills, canceled all credit cards, set December 1, 1971, as "lift-off." 7 a.m., December 1, I started up my VW bug and crossed the Hudson.

Now what?

I was scared. I felt barren and uncertain. "What have I done!" On the New Jersey turnpike, I stopped at a gas station and called a friend. "I've crossed the Hudson." She knew. She was hysterical with joy half laughing, half crying. My plan called for no further planning. No re-plays of old patterns. No more rigging the wheel of fortune. Let it spin. Let life itself take hold. "I'm riding co-pilot," I told myself. No destination. I started down the turnpike westward-bound. I had $5,000 with me, come what may.

I drove on aimlessly. In a day or so, I wound up at Yellow Springs, Ohio, where I visited an old friend at Antioch College. He had had a lot of experience with communal living, and I sought advice. After five days, I headed for San Cristobal, New Mexico, to take a look at the Lama Foundation, a spiritually oriented community. Days later, I drove up the long, winding, snowy mountain road to Lama feeling awkward and uneasy. I just presented myself on the spot and someone said, "Come on in and have some hot tea. I did. I liked what I saw. It was different, but okay. There was a deep sense of welcome. I needed that ... in the worst way.

Transition

I stayed at Lama on and off for six months. I renewed a spiritual search which had its serious beginnings right after World War 11, when I spent a few years studying with the Jesuits at Fordham University in N.Y.C.

In June of '72, I left Lama and headed blindly west once more. In Nevada City, California, I met a lady who had just returned from India, where she had spent some time at the ashram of Sia Baha, a renowned Indian spiritual leader. We talked for days. Inwardly, I rejected any notion of my going to India. Two weeks later in downtown San Francisco, I passed the Air India office, walked in and bought a round trip ticket.

India is a full story in itself. It's enough to say that I returned to the U.S. in December of '12 with life-threatening hepatitis. It took three months at the V.A. hospital in Albuquerque and a year and a half of slow recuperation in Taos for me to regain my strength.

I did odd jobs to survive. For a couple of years I was the morning waiter at Joe's Restaurant, where I earned the solemn title of Coffee Guru. One time a prominent ; Indian guru stopped in. As I took his order, he said, "I understand you are a guru." I replied, "Yes, but I'm a coffee guru." He said, "Ah, the very best kind."

One night going home from work at Joe's on my bicycle, I hit a pothole, fell, and crushed my right elbow. Back to the V.A. hospital for surgery and repairs. The success of the operation required that I remain absolutely quiet for four to five months until the elbow healed. I was financially broke and obviously couldn't work. I lived on disability welfare for the next five months. During the period of recuperation, I invented Hotsy Totsy.

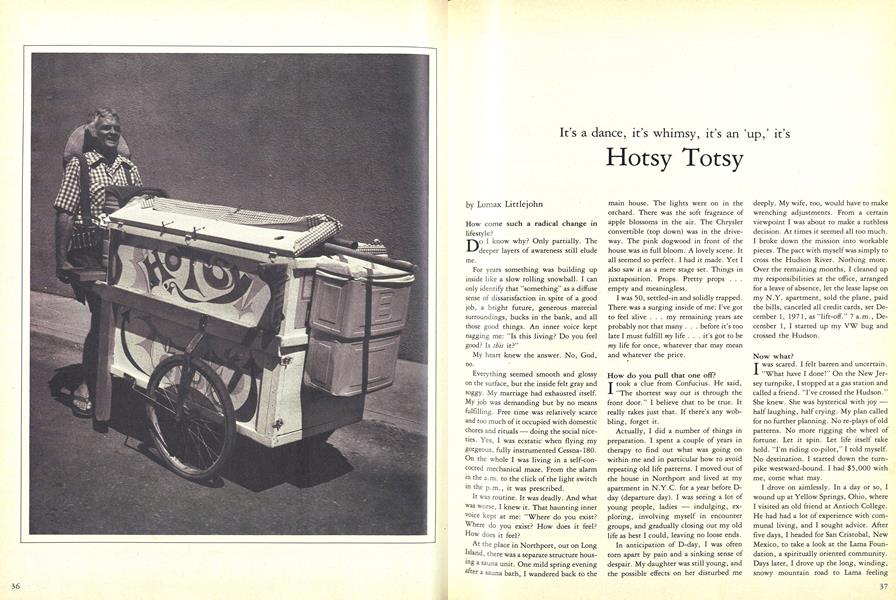

I had time to think it through in detail and sequence. When my arm improved, I was ready to go. And I didn't make any mistakes: 1) Be legal see a lawyer; 2) get approval from the department of health; 3) apply for a state tax number (sales tax) and a local business license. I borrowed money from some doctor friends in Albuquerque, built the wagon with the help of a carpenter friend, and started on April 4, 1976. That day I cooked the first hot dog I ever made in my life. Hotsy Totsy was an instant success. I brought home the bacon the first day and have ever since. I started serving only Oscar Mayer hot dogs and still do.

The First Year

THE hot dog vender is vulnerable. One time the cops threw me off the street. I was licensed (and they knew it), but they refused to acknowledge the fact. My attorney got me back on the street the next day. Some months later the town merchants came up with a proposal to outlaw all venders. I wasn't the real target, but I'd be the first victim. My lawyer said, "Can't help you. The issue is political, not expressly legal." Figuring I'd probably had it, I went to California at the end of the season and took a job in a doughnut shop to learn the operation. If Hotsy Totsy got wiped out, I'd open a doughnut shop in Taos and call it "Funky Dunky."

Funky Dunky never came to pass. At a town council meeting in the depths of February the anti-venders legislation would baired. I made an impassioned plea for Hotsy Totsy. The all-Hispanic town council unanimously approved the anti-vender ordinance and simultaneously granted me an exemption. So, one minute I was about to be thrown out and the next I had a monopoly. That's life . . . sometimes.

At this point Hotsy Totsy was launched. I weathered my initiation trials, and Hotsy was rapidly becoming the "institution" it is today. The large amount of publicity I received (and still receive) helped beyond measure. All of it has come to me gratuitously. I did not, nor will I ever, seek it out.

The early days had their frightening and desperate moments. The day the police kicked me off the street I lapsed into a decline. Dragging, I went to a local bar and had a couple. Hangover notwithstanding, I perked up the next morning when my lawyer called to give me the good news: "You're back in business."

Street venders are vulnerable. I take a fair amount of abuse. Some people give me lip and smart talk. Some get pushy. Some try to rip me off. I've sweated out attempted robberies. The day they held a knife at my back I went home with a bloody shirt. Mostly, people are wonderful. They're courteous, considerate, patient, pleasant and lots of fun.

The Hotsy Symbol

T TOTSY Totsy is my livelihood. It's free J- in its purest expression. I deliver an honest product at an honest price. And it's going to stay that way for my part. Yes, I raise prices with inflation but scrupulously in line with my exact product inflation and not one sou more. Today, a Hotsy Totsy (Oscar Mayer hot dog) with mustard, ketchup, relish, and onions plus a nine-ounce cup of good lemonade costs $1.05, tax included. One time, a local banker completed his lunch and asked how much he owed. I said, "A dollar five and if you don't have a nickel it'll be a dollar." This blew his bio-computer. Steam came out of his ears. He gave me a lecture about precision and money. I said, "Yes, but I'm a man of approximation." More steam came out of his ears.

Hotsy Totsy . . . the Quintessence

To me, Hotsy Totsy is a dance. I love the kids. They all know me. The little tots wave and say, "Hi ya, Hotsy.' When the school bus passes, the kids hang out of the windows and scream and holler. I love to play and fool with people and pass the time of day. Maybe swap a few lies. I also have a great rapport with the local dogs. Every dog in town knows me. They come up to the wagon and invariably put in their order. I always say, "No, this is not a dog restaurant." This happened one day when a tourist was passing. He heard me and announced, "I know it's not a dog restaurant, but I want to buy him one." "Okay," I said, and turning to the dog I asked him what condiments he wanted on his frankfurter. The tourist said, "He'll take it plain."

I assembled the hot dog and gave it to my four-legged customer. He wolfed it down. The tourist, with a wave of his hand, said, "He'll have another." I repeated the process. The dog gulped it down, belched, and walked away. The tourist paid me and sauntered into the park. A delicious episode', one I cherish.

And the lady who kept waving her driver's license at me. I was extremely busy. I said, "Look, lady, I'm not a traffic cop, I'm a hot dog vender." She wouldn't quit. I took the license and read it. I sa'id, "Lady, you've just won yourself a free hot dog." The license read: "Mrs. Totsy." ... and you've just won yourself a free hot dog." The license read: "Mrs. Totsy." ... and when I leasl expect it, I catch a loud "whahoo-wha" from Furber Haight, class of 1915.

Furber is a grand old gentleman of 84 with a twinkle in his beautiful blue eyes. He's a sweet guy. Furber had a birthday party a while back, and when it came time to say a few words, he was quoted as saying, "If I'd known I'd live this long, I'd have taken better care of myself." At one point in history Alan MacPhail '78 was tending bar directly across the street from Hotsy Totsy. Furber caught on to this and said as he passed the cart, "What d'ya know, Dartmouth's working both sides of the street."

For me, Hotsy Totsy symbolizes all that's important. It's a dance, it's whimsy, it's an "up." Yet it's for real. It has integrity. It's my livelihood (all of it). Hotsy Totsy is sheer paradox totally serious and not serious at all. It's a work of art.

I return home sometimes a little tired physically, but I feel light and alive. I don't take home any worldly anxieties or oppressive thoughts so characteristic of a world I once knew. Hotsy is at least half fantasy, ephemeral; it could evaporate to- morrow. It's a kind of sleight-of-hand, a piece of personal magic. It reflects all of what I love most in life.

I live in a tiny, tiny adobe house with a courtyard. It was once a shed. I pay $50 a month rent. I'm on the street six days a week from 11:30 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. When people complain because I'm not on the street longer, I pull myself up to my full six-feet-two, look them straight in the eye, and say, "I work sufficient hours for a man of my age and dignity:" I live on $4,000 a year and that's plenty for me. I don't owe any money. I'm solvent. I have everything I need. And, you know, I haven't a complaint in the world. When I had everything, I complained about everything. In the old days life was deadly serious. I was carrying around so much baggage fancy homes, cars, airplanes, executive positions, portfolios, Brooks Brothers suits, and the rest of the claptrap.

When you live lone in a tiny space, there is the tendency to give everything names. Now there's Frances. She's the big old Norge freezer in my bedroom. It's all quite proper - Frances is frigid. And then there's Mildred. Mildred's my faithful 1965 Chevy pick-up. And then there was Christine. She was my plant - a dieffenbachia. Well, we got into a hell of a fight and I threw her out. I'll tell you about that sometime. . . .

I live a simple life. I don't have TV don't want it. I have a few close friends here and in Albuquerque. I read - mostly classic philosophy, history, literature. I'm up at dawn, run a mile, prep for the wagon at my leisure, and the day is born. I've never had it so good.

Softie months ago, a lawyer from Albuquerque approached me with an elaborate written document concerning a franchise plan for Hotsy Totsy. Of course the scheme included my personal involvement somewhat in the capacity of a Colonel Sanders. The bottom line on all of this was that after three years my interest would be worth a million dollars. Up to this point, I'd said nothing. I looked at him and said, "What do I want with a million dollars?" One lawyer turned very pale and faded away.

Personals

IN the course of years, my wife and I reached a comfortable (and unspoken) understanding: In spite of all, she really knew and somehow accepted me for who I am. She died last year. Cancer.

My daughter Nancy just turned 24. We have a rich relationship. I adore her. She works for Young and Rubicam and is doing her M.B.A. at night. She loves it and she's treated well. We took a vacation together in California in October. I went east in December for the holidays. One time on a visit to Taos, Nancy pitched in and dished out the condiments on Hotsy Totsy. She definitely has a future in the business. (I don't know about Y & R, but certainly H-T.)

The Winters

THEY'RE tough. I don't make enough in the summer to see me through the winter. I do what I have to do. I've tended art galleries, managed cafeterias, waitered, worked in a machine shop (drill press operator), done time as a doughnut chef in training, a motel desk clerk, night watchman, house painter, and this year I'm working with a company that does income taxes. No matter what you do in Taos, the wages are always the same minimum, $3.50 per hour.

Dartmouth Education

I think it's perfectly lousy. Here I am at age 62, and all I can do is hustle hot dogs and qualify for a minimum wage. Well, maybe something brushed off. I have not allowed my mind to fall fallow. I read slowly and ruminate . . . and ruminate.

In the past couple of years, I've ruminated all of the translated works of Nietzsche, all of the Platonic dialogues plus a halfdozen scholarly books of commentary on same, all of the works of Carl Jung, most of Melville, Kafka, Hesse. Presently I'm into history and the philosophy of history. Regarding the latter, some insightful pieces by Dilthey, Croce, Toynbee, Butterfield, Niebuhr, Karl Jaspers. At the moment I'm ruminating 600 pages of history - The Western Experience by five historians associated with' U.C.L.A., Michigan, Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia.

I enjoy all of this. I love ideas - the ones that penetrate. And, too, I like to hold the widest possible perspective, especially in these heaving, hectic times. Newspapers provide very little by way of perspective. They're concerned with the truth of the moment, idea-less facts. If there's a soft spot in my life in Taos, it's the absence of an intellectual environment, which is part of the charm of this community. I wouldn't have it otherwise.

I've got a close doctor friend in Albuquerque and we share some of these high heady things. We also correspond. On the envelope I always include "M.D." after her name. She writes "D.H.D." (Doctor of Hot Dogs) after mine. People ask me about my D.H.D. where it was conferred, etc. I tell them Harvard.

That snotty note I wrote to Dartmouth to "get off my back" may be more clear now. From my view at that particular time, fund-raising, hyped-up alumni biosketches, and "our onward and upward progress" was more than I could take. I was fighting for my survival on the street.

Of course I understand the need for fund-raising and all of that. After all, I was in the racket myself at one time. At this point in my personal history that sort of thing comes across as intellectually insulting, nauseating pretense, if not grossly out of phase with the times. Must we keep on playing hero-games and fooling ourselves? There: I said it.

Skeleton in the Closet

T don't mention the name of the firm I once worked for in N.Y. The grapevine reveals that I'm a source of embarrassment to an otherwise old and prestigious PR and fund-raising organization. I was a senior vice president. I was also on the executive committee and the board of directors — also involved on Wall Street, a registered representative of the exchange. In my earlier life I worked for the N.Y. Daily News. Then a professional social worker. My beat was Brooklyn and Harlem. Then institutional fund-raising. You see, I've lived a checkered life ah, but not a dull one.

Oh, yes, now about my bees. They were a disturbing factor on the wagon. Customers were afraid of being stung. On one particular occasion an older lady was about to order a hot dog and began edging away when she saw the bees. Spontaneously, I said, "Benson, I've told you never to come around during business hours. I'll play with you later." The customer bowled me over when she said, "Do you know him?" I said, "Madam, you don't think I'd speak to a stranger that way do you?" Fearlessly, she stepped up to the wagon and ordered.

I recognized that I was on to something. Once people think you're in control they're no longer uneasy. When the bees come up to the wagon, I just call them by name (Benson, Russell, Elliot, Harold Otis, Sidney, Roger, etc.) and command them to either leave or behave themselves (In fact, they've never stung anyone except me.) People love it. They call me the beemaster. They even inquire after the bees: "Have you seen Russell today?"

Postscript

After April 15, I'll open my sixth season as Hotsy Totsy. I'm already planning. This year I'll paint the wagon afresh, spruce up my umbrella, and sharpen up my hawking call: "Get 'em while they're hot!"

Lomax Littlejohn is a member of the class of1943.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

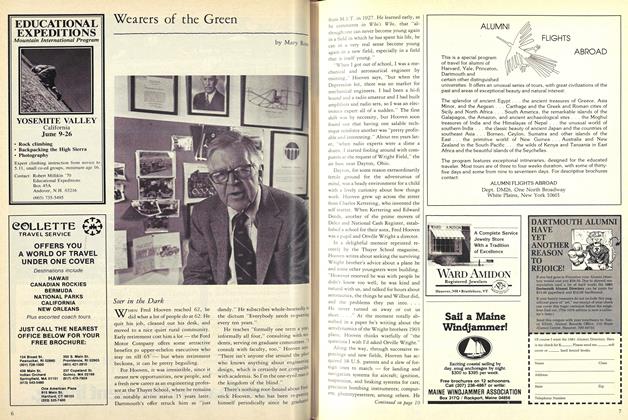

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

April 1982 By Robert D. Blake

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1969 -

Feature

FeaturePlainfield, New Hampshire $295,000 and up

APRIL 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFashion Corner: Two Outing Club Looks

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni and Tuck Faculty Join In Study of Stock Ownership

January 1955 By JAMES P. LOGAN -

Feature

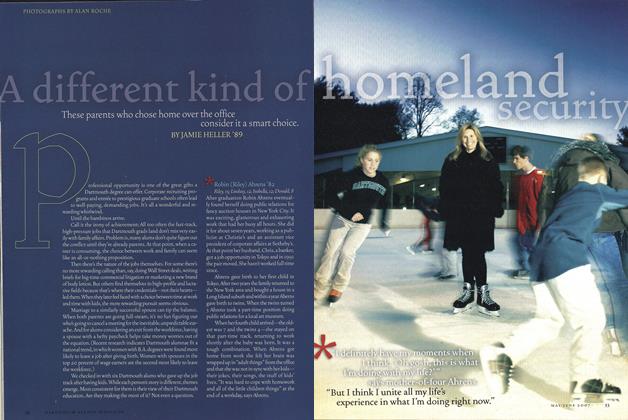

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May/June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNew Edition of Webster Papers

MARCH 1968 By John Hurd '21