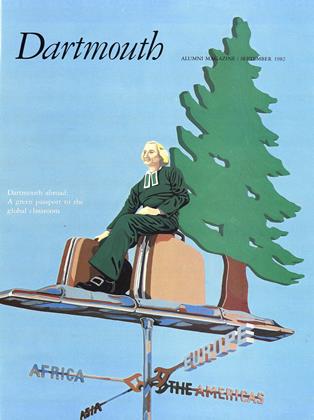

The foreign-study program to end them all is just around the corner, says Dartmouth astronomer Delo Mook, who claims that the space shuttle is the first step toward an orbital classroom. Until then, however, Dartmouth foreign study will remain earthbound, though it is not likely to suffer any other limitation.

What began in 1958 as a fall-term foreign-study program for French and Spanish majors only is now a movable feast of options for everybody. Dartmouth undergraduates can study French in Quebec, Aries, Blois, or Lyons; Italian in Siena; German in Mainz; and Spanish in two towns in Mexico and one in Spain. Beyond introductory language study, there is a geography program in Mexico; one in African and Afro-American studies in Washington, D.C.; one in urban studies in Boston; and one in philosophy in Edinburgh. Students can study art in Florence, Italy; government in Washington or London; religion in Scotland; or environmental problems in Kenya. If it is advanced literature and civilization they want, they can do the French in Toulouse, the German in Berlin, and the Spanish in Puebla, Mexico, or Salamanca, Spain. For the Italian, they go to Florence; for the English to London; for the Russian to Leningrad; and for the Chinese to Beijing in the People's Republic. They can do ancient Greek civilization via studious peregrination over Greece, ditto ancient Roman civilization over Italy. An interest in tropical biology can take them to Central America and the Caribbean, and the earth sciences program will spirit them from outcroppings in Enfield, field, New Hampshire, to outcroppings in the Catskills and the western United States and then up a Caribbean volcano.

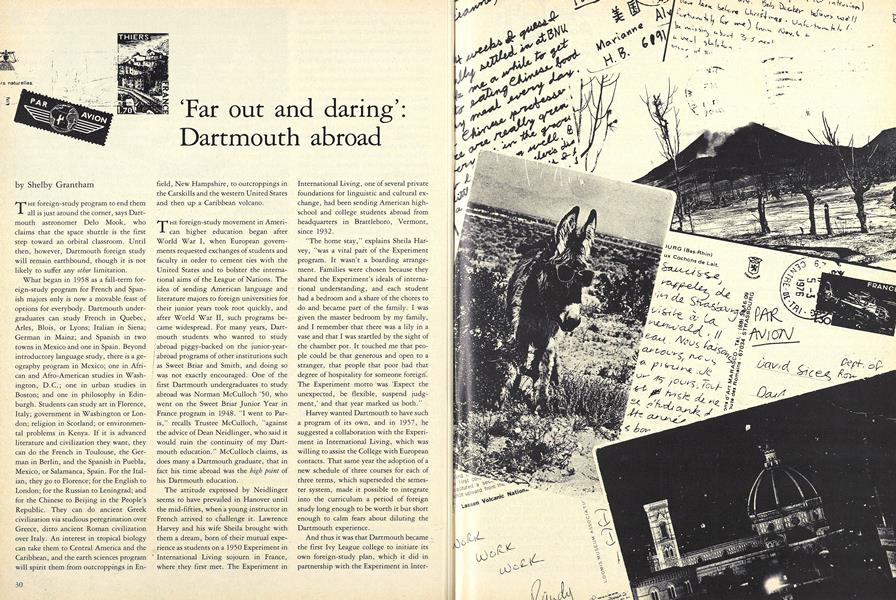

THE foreign-study movement in American higher education began after World War I, when European governments requested exchanges of students and faculty in order to cement ties with the United States and to bolster the international aims of the League of Nations. The idea of sending American language and literature majors to foreign universities for their junior years took root quickly, and after World War II, such programs became widespread. For many years, Dartmouth students who wanted to study abroad piggy-backed on the junior-year-abroad programs of other institutions such as Sweet Briar and Smith, and doing so was not exactly encouraged. One of the first Dartmouth undergraduates to study abroad was Norman McCulloch '50, who went on the Sweet Briar Junior Year in France program in 1948. "I went to Paris," recalls Trustee McCulloch, "against the advice of Dean Neidlinger, who said it would ruin the continuity of my Dartmouth education." McCulloch claims, as does many a Dartmouth graduate, that in fact his time abroad was the high point of his Dartmouth education.

The attitude expressed by Neidlinger seems to have prevailed in Hanover until the mid-fifties, when a young instructor in French arrived to challenge it. Lawrence Harvey and his wife Sheila brought with them a dream, born of their mutual experience as students on a 1950 Experiment in International Living sojourn in France, where they first met. The Experiment in International Living, one of several private foundations for linguistic and cultural exchange, had been sending American highschool and college students abroad from headquarters in Brattleboro, Vermont, since 1932.

"The home stay," explains Sheila Harvey, "was a vital part of the Experiment program. It wasn't a boarding arrangement. Families were chosen because they shared the Experiment's ideals of international understanding, and each student had a bedroom and a share of the chores to do and became part of the family. I was given the master bedroom by my family, and I remember that there was a lily in a vase and that I was startled by the sight of the chamber pot. It touched me that people could be that generous and open to a stranger, that people that poor had that degree of hospitality for someone foreign. The Experiment motto was 'Expect the unexpected, be flexible, suspend judgment,' and that year marked us both."

Harvey wanted Dartmouth to have such a program of its own, and in 1957, he suggested a collaboration with the Experiment in International Living, which was willing to assist the College with European contacts. That same year the adoption of a new schedule of three courses for each of three terms, which superseded the semester system, made it possible to integrate into the curriculum a period of foreign study long enough to be worth it but short enough to calm fears about diluting the Dartmouth experience. .

And thus it was that Dartmouth became the first Ivy League college to initiate its own foreign-study plan, which it did in partnership with the Experiment in International national Living. Two years after the first two tiny groups of juniors and seniors went ofF to the universities of Caen, France, and Salamanca, Spain, Harvey was able to report to the Conference of Undergraduate Study Abroad in Chicago that Dartmouth had pioneered a new type of foreign-study program, one that was being recommended by the Experiment as "the best thought-Out program now in operation."

Feeling that foreign university courses were often too specialized for the American undergraduate and that literary criticism on the Continent was outmoded, the faculty involved had designed a program limited to one ten-week term, with literature courses to be taught by the foreign faculty but designed especially for Dartmouth students, and in which language study was focal. The Dartmouth Foreign Study Program (F.S.P.) was based on the Experiment ideals of a home stay and location in the provinces rather than in the overcrowded, often inhospitable capital cities with their great concentrations of foreign students. It was restricted to Dartmouth students.

About 1964, the partnership with the Experiment was dissolved, and Professor of French George Diller, who had taken early retirement and moved to France, became the College's agent in Europe. That same year saw another important change. The niggardly budget that was to plague the effort for many years (causing Diller to write hotly mis-typed letters of outrage from the Cote d'Or) had meant that at first no Dartmouth faculty were spared to accompany the students. But by 1964, the academic aims of foreign study had sharpened, and the directors wanted Dartmouth faculty in residence abroad. After another tussle with the keepers of the coffers, it was agreed that, as an experiment, one faculty member each could accompany the 1964 French and Spanish progams, "It was all very far out and daring," recalls Harvey.

But it worked, and more and more glowing reports came back to Hanover. Then, foreign-language study in the United States took a nosedive. In the late sixties, schools and colleges across the nation (including Brown, Stanford, and Yale) started dropping their foreign-language requirements. Dartmouth, just about to climb on the bandwagon, was stopped in its tracks by a survey that showed, to the unanimous surprise of the faculty study committee, that most alumni thought the language requirement had been worthwhile and should be continued. That, together with Harvey's testimony that language instruction at Dartmouth was then in the process of a "profound change," led to the continuation of Dartmouth's requirement.

THE profound change was a move away from the reading of literary texts toward an emphasis on spoken language. This new direction sprang from the intense convictions of another linguist with a dream, John Rassias, who felt with every flamboyant bone in his body that communication, not correctness, was the secret.of language teaching and learning. Rassias had come to Dartmouth in 1965 to teach a crash course for Peace Corps volunteers, an exercise that convinced him that dramatic and intensive measures were the key to turning language teaching around in this country. He stayed on to teach Dartmouth undergraduates, hollering, 'Damn the mistakes full speed ahead!" and he dramatically overhauled elementary language instruction at the College. Introducing professorial embraces for good answers, costumed performances, and rapid-fire drills, Rassias created for Dartmouth an Intensive Language Model that has made the small college on the hill a Mecca for despairing teachers of language.

It was a logical next step, says Professor Rassias, to add to the courses he had designed an overseas experience. In 1967, the foreign-study program was put under his direction, and the following year the Dartmouth Language Study Abroad (L.S.A.) program was born. Rassias had worked with Diller and other faculty members to set up this second species of foreign study, designed for beginners. The idea was a one-term course (later expanded to two terms) in Intensive Language Training in Hanover, followed by a term of language study abroad.

Students were to have the option of satisfying Dartmouth's foreign-language requirement by going on an L.S.A. program. gram. The success of the intensive teaching on campus coupled with the opportunity to discharge the requirement in two or three terms, one of them abroad, was an unbeatable combination. In the 14 years since its inception, L.S.A. has outstripped even F.S.P., and it accounts for the greatest expansion of foreign study at Dartmouth. In 1982—83, 432 Dartmouth students will go abroad on L.S.A. Adding the 357 booked for F.S.P. brings the total number of Dartmouth students, who will be on foreign soil next year to 789 nearly a fifth of the undergraduates.

The distinction between the venerable F.S.P. and the younger L.S.A. is in many ways just that: a function of maturity, both chronological 'and academic. Although both types of program are open to all Dartmouth undergraduates, a higher level of prerequisite coursework effectively limits F.S.P. to juniors and seniors, and the introductory nature of L.S.A. appeals more often, though by no means totally, to first- and second-year students. Ellen Rose, former Dartmouth professor of English, makes this unminced distinction between the two: "The L.S.A. program offers students the opportunity to learn a language by speaking with natives and living in families where they are forced to do what they are too lazy to do otherwise. It also gives them a chance to experience language as part of a whole culture. The F.S.P. is a more sophisticated exposure to another culture through the vehicle of academically respectable work." Also, since the mid-sixties, F.S.P. has been open to other disciplines, and its more traditionally academic goals have broadened beyond the advanced study of literature and civilization to include some of the sciences and the social sciences.

Students often refer to L.S.A. archly as "The Trip," a phenomenon that Professor of French and Italian David Sices '54 analyzes this way: "It is part of the myth of L.S.A. that it is essentially an 'experience' and not an academic experience. For some reason, the people who participate in it tend to forget that they spent more time in class on L.S.A. than at Dartmouth an average of five hours a day. It's very structured and very intensive." The other side of this myth, says Sices, is the myth of mastery: "There aren't any miracles. That's exaggerated. Even at a higher level, it isn't true to say they achieve some kind of mastery but it does make them aware that there is more out there than they ever imagined before. What we do abroad, because of its philosophy and the intellectual efforts of individual faculty, is probably as good as anything that can be done at the college lever to prepare students to learn language and culture. And you wouldn't get the same thing out of five or six years of college French at home."

A CADEMIC instruction on both F.S.P. is a mixture of courses given by the faculty of the foreign institution and others taught on site by the accompanying Dartmouth professor. In some cases, such as the Leningrad F.S.P., in which Soviet conditions stipulate that only Russian faculty shall be used, the Dartmouth faculty member is only an adviser to the students. In others, such as the earth sciences F.S.P. that hops from country to country and spends most of its time on an outcropping outside a tent, the Dartmouth faculty do all the teaching.

Taking an F.S.P. or an L.S.A. program out is in many ways a severe distortion of faculty life, according to Sices, especially in small departments that run a number of programs annually. "We try to work it on a rotation system, once every 18 months, but even then it's too much. Faculty members have to disrupt their own families, rent their, houses, take their children out of schools, and forego research to take on three months of very intensive activity teaching, counseling, deaning, administering, disbursing, dealing with broken legs, ruptured appendices, abortions, alcohol abuse, terminal cancer diagnoses. It really is one of the last surviving examples of being in loco parentis."

The faculty who take these programs out say they feel their responsibilities abroad more than they do in Hanover. Just keeping track of 15 or 20 young adults in a strange setting is a draining proposition, and some settings pose particular difficulties. The tropical biology F.S.P., explains Professor Richard Holmes, is subject to "all kinds of nasty things" venomous snakes, stinging ants, poisonous spiders, dysentery, malaria, and bot flies among them. There have been no accidents on that program to date, but as biology instructor Thomas Sherry '73 points out, heads have to be counted continually.

Professor Robert Russell of Romance languages speaks, too, of the difficulty of supervising foreign professors, which requires diplomacy: "They are distinguished people, and, of course, you never visit their classes. It simply isn't done, but at the same time you have to keep track of what's happening with your students' education." Politics can also be a problem, explains Russell, who taught in Spain before Franco's death, when classroom visits from the secret police not very cleverly disguised as students were common.

Professor Gary Johnson of the Earth Sciences Department moans philosophically about logistical hassles: "All nine of us in the department sit down each year to decide the calendar and work out the costs. It's a tight schedule, getting us all from Enfield to Utah to Costa Rica in one tenweek term, and we can't predict the number of majors one year to the next. Are we going to need three houseboats on Lake Powell, or two? We rent boats and book cabins and cope with dying airlines. Basically, we run tour groups."

Culture shock is sometimes, though not very often, a problem that extends beyond the first couple of weeks, and it afflicts the younger students on L.S.A. more often than the more adaptable F.S.P. students. Lucy Stewart of the Office of OfF-Campus Programs explains the syndrome this way: "You are going out with a mission. You are high about it. Then you have difficulty with communication. You get uncomfortable. You can't be effective in carrying out your goals. You feel like a failure. You get depressed. It sometimes takes the mild form in our students of sleeping a lot, or hanging around with fellow students because they're not up to handling the effort of speaking another language all day long at the three-year-old level."

Student discomfort sometimes takes the form of a retreat to familiar patterns in inappropriate settings. One L.S. A. faculty member recalls discovering that every Wednesday night the members of a certain fraternity (all three of them) were having a house meeting. "That," observes Russell with a tolerant grin, "is not taking full advantage of the opportunities. But you've got to realize the insecurities they feel." Occasionally, insecure Dartmouth youngsters skirt real danger. There is the odd heart-stopping skirmish with local police, and Professor of Russian Richard Sheldon remembers one harrowing term in Leningrad when he spent an entire fortnight meeting with Soviet authorities trying to convince them that the Dartmouth student who had been caught stealing a flag in Estonia should be allowed to stay in the country and finish the program. He failed and the student went home. Rose recalls a similar problem, when some Dartmouth students became loud and arrogant in a pub in Yorkshire and started a fight with some English lads. Words were exchanged and rocks were thrown before the Students could be dragged back to the hotel. "It was an ugly incident," says Rose, "but it was redeemed by what happened as the year progressed."

WHAT happened what usually happens on a foreign-study program goes beyond the standard academic experience. "There is a stretching of the mind and spirit that results from exposure to what is initially unfamiliar," says Russell, who explains that one of the first reactions to the unfamiliarity of a foreign-study situation is a salutary humility. He recounts the occasion on which a student came to him early in a program and said, in genuine amazement, "Professor Russell, I can't believe it! There's this kid in my family. She's only three. And she speaks perfect Spanish!" One student discovered that not being able to chatter constantly without saying anything forced him to learn how to listen. As another put it, "Once you've been humbled enough to be put on the spot and have others interpreting what you are thinking because you can't really say it, you become more aware that other people think other ways." Biologist Sherry, prompted by his wife, recalls that when he returned from his undergraduate L.S.A., his sisters told him he had become a human being while he was gone. Sherry remarks (with salutary humility), "I must have grown up quite a bit."

The unfamiliar situation does not depend solely on an encounter with a different language, as English major Peter Heller '82 discovered on the tropical biology F.S.P. "I have never walked so softly"or in such perpetual awe as in the rain forests," he wrote in a letter to his grandmother. "A human being here is a small thing. Walking through these rain forests, you can't help feeling again what it is to be a child. Every step is filled with novelty, strangeness, magnificence. I feel very lucky to have seen them while there are still jaguar tracks in the wet sand."

The experience of second childhood is, of course, cushioned by the family setting Dartmouth is careful to provide whenever possible. It does happen, according to Sices, that a family doesn't work out, but a real mismatch is rare. There are occasional misunderstandings, especially at first, and students are always warned beforehand of three basic no-nos: long showers (energy is precious abroad), telephone calls (each one must be paid for), and refrigerator raids (nobody ever raids a refrigerator abroad).

But even the misunderstandings are often the stuff of learning, as Lucy Stewart of Off-Campus Programs explains: "The program director told a student in France he should bring a picnic the following week. The student's idea of a picnic was leftover salami, some cheese, and a hunk of bread, and he didn't tell his French mother about it until the night before he needed it. She had a fit. Her idea of a picnic was quiches, fruit tortes, sliced meats, cheeses, and fresh bread none of which she had in the house. The student was confused, but they talked about it, and he discovered he had been unintentionally inconsiderate, and he learned to abstract that and watch out for it in other situations. Another student enjoyed reading late into the night, and one midnight, the French father switched off the master electricity. What did that mean? What was the message? The student was upset, but again, they talked, and it turned out the father had simply assumed he was asleep with the light on."

The family is also the setting for the little miracles. "It took me four weeks to be able to talk at the dinner table," recalls Marie Furnary '82 of her French L.S.A. "Before I got to that point, I could understand that they were forever saying to each other, 'Did she understand what I said?' and 'No, she didn't understand.' They were delighted when I finally started talking and it was because they were all smoking a lot and I wanted to tell them it was bad for them. They loved it." Another student, whose foreign father spent every spare hour in a small garden outside the town, accompanied the man, and they had long conversations about life in France while they gardened, conversations the student describes as "among the most privileged moments I have had."

It is difficult for people who have not had the experience to appreciate the depth of the familial ties established on these programs. "At first it struck me as funny, all the talk among students about 'French brothers and sisters,' " says Sheldon. "That seemed awfully strong. But I came to realize that they really feel that way. That degree of closeness does develop, and often those brothers and sisters end up coming here as well." Sheldon reports that even in Leningrad, where family placement is not allowed and students live in dormitories, they get invited to homes and apartments by their teachers. "At the farewell banquet," he says, "there are always tears. The Russian teachers have been taught to see us as evil, but these kids have worked hard on their Russian to be there, and they are pretty irresistible."

The students' discovery that not only can they survive away from home and family, but they can even prevail and develop a second family engenders a new sense of independence and confidence in them. Parallel to it develops an almost paradoxical bonding within the Dartmouth community abroad. The professors who take these programs describe them as intensified classrooms and speak of a ripple effect that continues long after the group returns to Hanover.

"I was not so much their teacher as their guide and mentor," recalls Rose of her 1979-80 London F.S.P. group. "I was the liaison between them and the institution, in loco parentis, in charge of them and watching over their behavior and welfare. Not an authority figure, but an aide. It was different from teaching in Hanover." She pauses and smiles, remembering. "I feel very warm toward that group of students. Paradoxically, I feel I taught them more in terms of values than I can do in the regular classroom. It was a function of time, and also of the kind of conversation you can get into on a train to Yorkshire. My aesthetic, personal, and political values came out very naturally. There is an analogy to parenting: Parents do not always teach principles explicitly they live them."

Rose remembers entertaining students in her home in Hanover in an attempt to break down some of the artificial barriers between them. "But," she says, " I think it happens only in that kind of enclave situation a limited number of us, my other-than-teacher relationship to them, our joint limited resources, our being 'captive' together in a foreign culture. It was like a marriage from which there was no divorce, a marriage that had to be negotiated."

One department organizes its entire program around the principle of facultystudent bonding. "The earth sciences program is required of all majors," explains Johnson, "and all nine faculty members are involved each year. We integrated three courses in the one program in order to have the students interact with all members of the department as early as possible in their academic careers. It's musical chairs for the faculty every faculty member is with the group for two to three weeks but the cohesion benefits us."

"The quality of student life is so much better there than it is here," asserts Russell. "There is a continuum of the academic. and the non-academic. In Hanover, we have 'student turf' and 'faculty turf.' Very little turf on these programs is not common ground." Holmes agrees: "There's a special camaraderie among the group, a bonding. A foreign country makes them pull together.".Participants often cite foreign study as a real alternative to the fraternity system, and Sices describes how he and the members of an Italian L.S.A. continued to meet together, often over dinner at his home, until all the students had graduated.

THE burgeoning success of these pro-L grams has, however, lately raised the specter of saturation. Some of the expansion is being directed now toward Asia and Africa. One of the finest feathers in Dartmouth's academic cap was the recent invitation from the People's Republic of China to establish a Dartmouth foreign-study program at Beijing Normal University, an invitation made on the basis of B.N.U.'s appreciation of the exceptional quality of the Dartmouth students of Chinese who had gone in past years to Beijing on the University of Massachusetts' China program. The invitation was accepted with alacrity, and the first Dartmouth-at-B.N.U. group went out last year. The newest program, about which students are very excited, is the environmental studies F.S.P. in Kenya, where students will study first-hand such situations as deforestation, water shortage, tropical disease, and over-population in a country that, despite the largest population growth rate in the world, is coping tolerably well with development. In addition, President McLaughlin is said to be seriously interested in redressing the .College's neglect of Hispanic culture, and that may lead to more programs in Latin America.

In the meantime, however, the popular Romance language programs are under serious pressure. The overwrought French and Italian Department offers nine L.S. A.s and four F.S.R.s every year, and this past year the demand, coupled with pedagogical problems at the Bourges site, led to a contested decision to move the Bourges L.S. A. to the metropolitan center of Lyons and expand it to an unprecedented 40 students. Professor Stephen Nichols'58, who chairs the department, describes the departure as a "natural evolution" and points out that the students will be divided into separate groups of 20 each. "Lyons is a second-generation L.S.A. site," says Nichols. "The pressure on L.S. A. was such that it was imperative to experiment with different solutions. There were not enough cultural advantages in Bourges, and we were having trouble finding enough families to keep the program working there. We decided to try placing two groups of students in the exciting urban center of Lyons, where we have a university connection that makes available to us one of (France's most advanced teachers of French as a foreign language. There are no other American programs in Lyons, and the Lyons situation allows us to expand or contract according to need."

Nichols says that if student reports are any indication, the Lyons experiment is a success, but other faculty are anxious about it. "Forty students," mutters Harvey. "It's a betrayal of the whole idea." Rassias, too, says he questions this kind of expansion of L.S.A. "You can't be a foreigner in the second largest city in France!" he says. "In a small setting we have total control classroom control, atmospheric control, the thing is fully in our hands. I can set up an interview for a student with the prefect the governor of Blois because I know everybody in town. Why tamper with a successful model?" Rassias pauses and then sits back. "The irony is that it's going to work," he says. "The experience overseas will always be a good one. A big center in France will be good." He leans forward again. "But in a small center, the experience would be devastatingly good!"

There is also the matter of reciprocation. Dartmouth sends a great many students abroad. Very few foreign students come to Dartmouth and the national figures put this imbalance in a glaring light. The Experiment reports that there are some 313,000 foreign students enrolled in colleges in this country and estimates the number of American students abroad at only 65,000.

The largest single reason for Dartmouth's scanty reciprocation is probably space. Since coeducation was instituted on an add-women-but-don't-subtract-men basis in 1972, beds have been scarce at Dartmouth, and part of the current administrative support of the foreign-study programs is due to the need to get a healthy number of Dartmouth students off the campus each term so there are beds enough for the rest. Of course, it is true that money is tight for foreigners. And it is true that Europeans who want to learn English often go to England, which is closer. And it is true that most foreign-university curricula are not flexible enough to accommodate within the degree a year abroad. But for those very reasons, many of Dartmouth's foreign-study faculty feel, the initiative ought now to come from us.

"I think Dartmouth ought to extend itseif more," says Rassias, who has himself been making efforts in that direction through a new program known as Language Outreach Education. Through it he has done such things as arrange for 50 Upper Valley families to host 50 French families from Blois for three days during the Bicentennial; set up a Spanish course in Hanover for New York Transit Authority police; and bring 35 Japanese students and teachers to Hanover for a three-week home-stay course in the Rassias method of teaching English. He also hires qualified Dartmouth students on their leave terms to go abroad and teach English where they are wanted. Currently, he is mulling over an exchange of parents.

Russell's "fondest dream" is reciprocation on an even larger scale. "Prestige," he explains, "is important to Europeans, and if the schools of the Ivy League, or the Pacific Coast Conference, for instance, could investigate together the possibility of offering an academic year tailored to the academic year of Europe, and also investigate cooperative financing, and allow some student choice, but for the most part send those interested in, say, biochemistry, to Dartmouth, and those interested in French literature to Yale, and so forth. ..."

BUT ballooning growth and exploitation anxieties aside, the College is clearly committed to the modern Dartmouth experience an enriching integration of the familiar and the foreign, an education in complexity and perspective. The College seems now to be dedicated to the proposition that its work goes beyond the nurture of nestlings and includes the fledging of citizens of the world. Maybe that is what liberal arts is all about.

MIT LUFTPOST PAR AVION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77 -

Class Notes

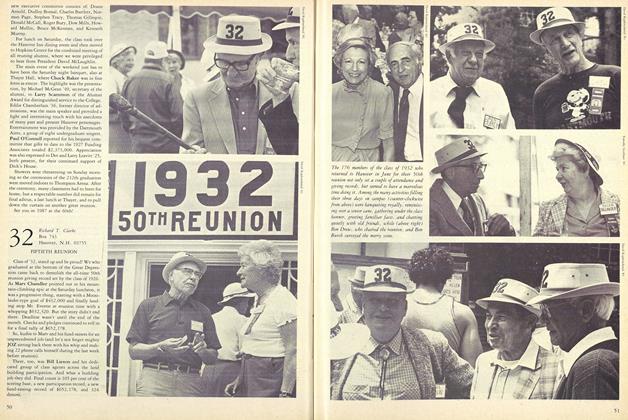

Class Notes1932

September 1982 By Richard T. Clarke

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

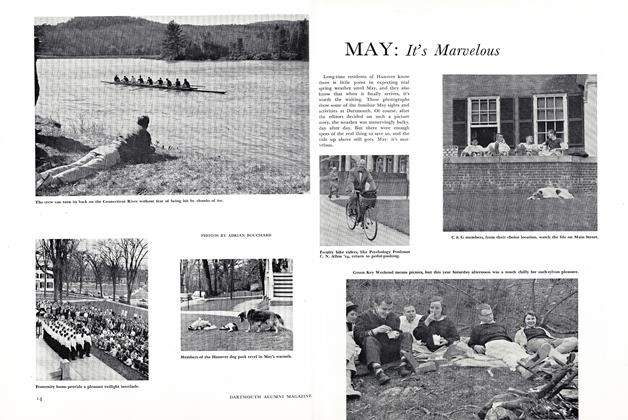

FeatureMAY: It's Marvelous

June 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAvalanche Authority

JUNE 1973 -

Cover Story

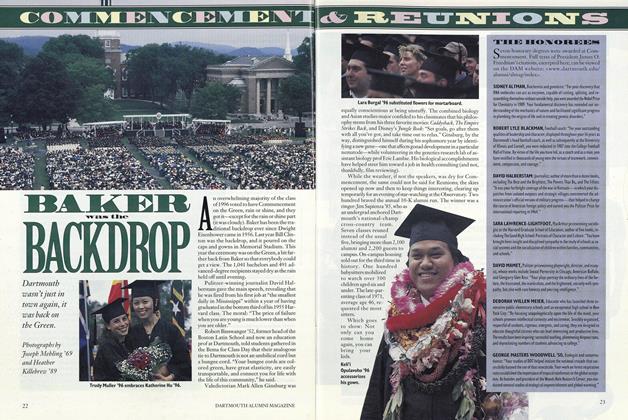

Cover StoryBAKER WAS THE BACKDROP

SEPTEMBER 1996 -

Feature

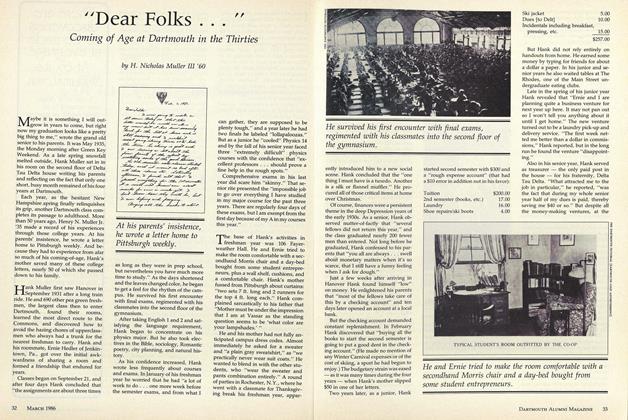

Feature"Dear Folks..."

MARCH • 1986 By H. Nicholas Muller III '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

MAY 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

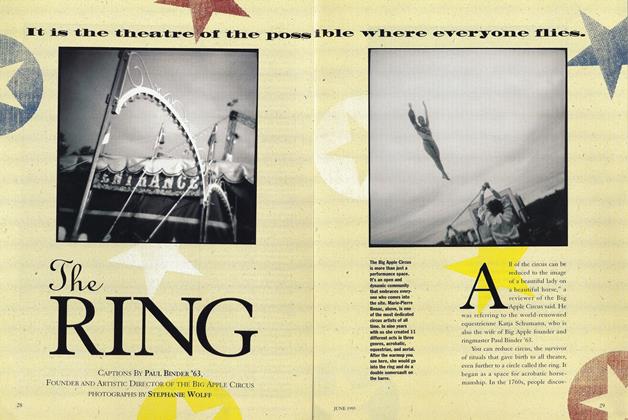

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe RING

June 1995 By Paul Binder '63