Last summer President McLaughlin andhis wife, Judy, spent a month traveling inmainland China, Hong Kong, and Australia. While in China President McLaughlin visited Dartmouth students andfaculty members who are teaching andstudying at Beijing Normal University aspart of Dartmouth's foreign study programand examined priorities in the Chinese educational system.

Our travels over a period of four weeks within the central and eastern provinces of China took us to nine major cities, five universities, and innumerable small towns along the way. Although physically demanding, the experience was exhilarating from the standpoint of the opportunity it afforded us to observe the world's largest nation as it enters into a period of political, economic, and social change.

Contrasts arising from China's current state of emergence are ever present: members of the younger generation dress in a western manner and openly demonstrate affection, while their less materialistic (and somewhat disapproving) elders maintain, by and large, the drab clothing styles of past decades and are decidedly more restrained in demeanor; the energy and skill exhibited by the new breed of Chinese "free market" entrepreneurs stand in sharp juxtaposition to the planned communes and the inefficient and bureaucratic infrastructure of state-run hotels, utilities, and transportation systems; the centuries-old practice of using animal and human labor to construct buildings, roads, and monuments appears increasingly ineffective in the face of the magnitude of the tasks involved in the national ambitions to introduce advanced technologies to the nation. All of these and other circumstances provide evidence of the significant changes in progress.

Nowhere was a sense of urgency regarding transition more evident than within the educational arena. The Minister of Education in Beijing identified the country's immediate goals to be the achievement, at the primary and secondary levels, of a total of nine years of mandatory schooling for all Chinese children and the preparation of the nation to enter commercially into the world economy.

In pursuit of these objectives, the Chinese government has established priorities for the education of teachers, lawyers, financial specialists and managers, and technicians for computers and in the sciences. However, with only five or six percent of Chinese students presently going on to advanced studies in universities or colleges, the task of leading the nation through such educational preparation is formidable. On top of this, China must also labor under handicaps imposed by the period of the "Cultural Revolution" - a decade of social turmoil, during which time teachers, as well as the intellectual community, were persecuted and the doors to the educational systems of the nation were closed. Generations of scholars and teachers were lost, and the effects are especially noticeable today in the faculty ranks of the university system where there are relatively few middle-aged professors.

In an attempt to develop the next generation of faculty, and in recognition of the fact that Chinese graduate programs may not be fully competitive with western graduate studies, the Chinese are interested in sending their brightest young teachers to the United States for post-doctoral work under the best faculty available at our universities and colleges. This provides a unique opportunity for institutions like Dartmouth to have their students trained in Chinese-language studies, within the Chinese educational system, in return for agreeing to finish on this side of the Pacific training of young Chinese faculty members. When I commented on the potential added value of the liberal arts with respect to what could be gained from establishing formal affiliations with United States institutions, the Minister of Education responded that functional specialties were more important from his standpoint and that of his countrymen. He added, with a wry smile, that after thousands of years of advanced civilization, he was confident the Chinese were sufficiently proficient in the humanities and the arts.

Perhaps the most revealing discussion I had concerning the state of the Chinese government's commitment to change was when I talked with several officials in the Ministry of Education. Our conversation focused on the evident lack of compatibility between the needs associated with academic freedom and a critical pursuit of truth, on the one hand, and a political system that, on the other hand, seeks to control the thought processes of its people. Their position on this was that changes in the environment of both academia and the political sphere must be paced and coordinated, so that one did not get out ahead of the other "as was the case in Iran." The fact that there existed a recognition of this dilemma, as well as willingness to discuss it, struck me as being encouraging in terms of the role of education as, potentially, a leading agent for change in this remarkable nation.

The most pervasive concern voiced by the Chinese we met at the universities, in factories, on trains, and elsewhere related to an uncertainty, and perhaps even a skepticism, over the probable consistency and durability of government policy. The life-style stress between generations; the competitive pressures between a controlled economy and a capitalistic system; and the whole question of the tenure of a popular group of aging government leaders - all of these are set against a centuries-old tradition of feudalism as the dominant force or faction in the history of the Chinese civilization. Men and women seem to rejoice in their new-found freedoms within China, but they seem, at the same time, to keep looking over their shoulders, unsure as to whether policies may not be reversed.

Given the potential of China to impact our global society, it is a country that will surely require careful and sympathetic observation, as well as cooperative international support, in the years ahead. Pertinent to this, the success to date of Dartmouth's Asian Studies and language programs in China are to the College's great credit, and they are reputed to be the most effective programs of their kind in existence.

In the years ahead it will be incumbent upon Dartmouth's faculty and administration to increase our academic emphasis on the entire AsianPacific Basin. Undoubtedly, the lives of our students will be influenced in significant ways by developments within the societies of that region, and the course of world peace may in large measure depend upon the understanding that our leaders have of the history, language, and culture of these great nations.

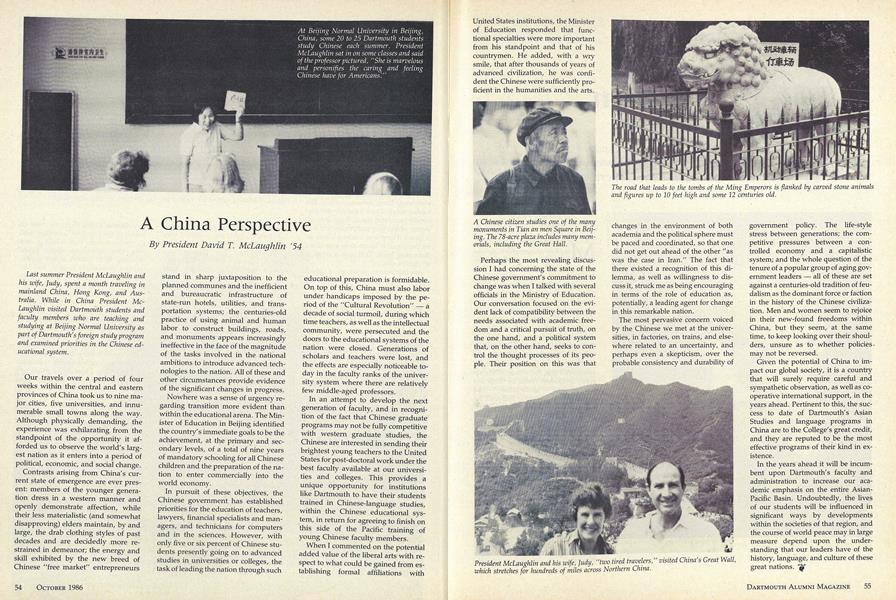

At Beijing Normal University in Beijing,China, some 20 to 25 Dartmouth studentsstudy Chinese each summer. PresidentMcLaughlin sat in on some classes and saidof the professor pictured, "She is marvelousand personifies the caring and feelingChinese have for Americans."

A Chinese citizen studies one of the manymonuments in Tian an men Square in Beijing. The 78-acre plaza includes many memorials, including the Great Hall.

President McLaughlin and his wife, Judy, "two tired travelers," visited China's Great Wall,which stretches for hundreds of miles across Northern China.

The road that leads to the tombs of the Ming Emperors is flanked by carved stone animalsand figures up to 10 feet high and some 12 centuries old.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

October 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

October 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

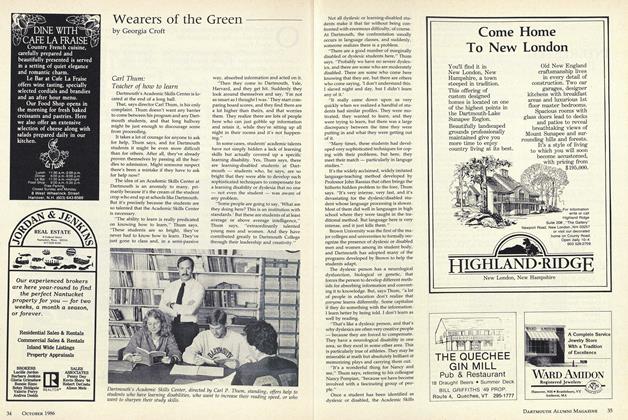

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

October 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70 -

Article

ArticleGetting to the root of the problem

October 1986

Features

-

Feature

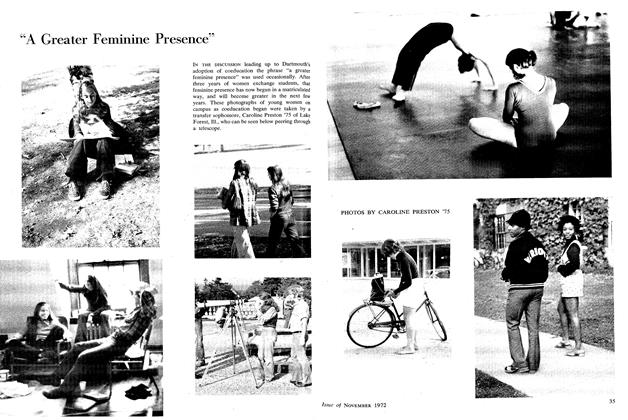

Feature"A Greater Feminine Presence"

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Feature

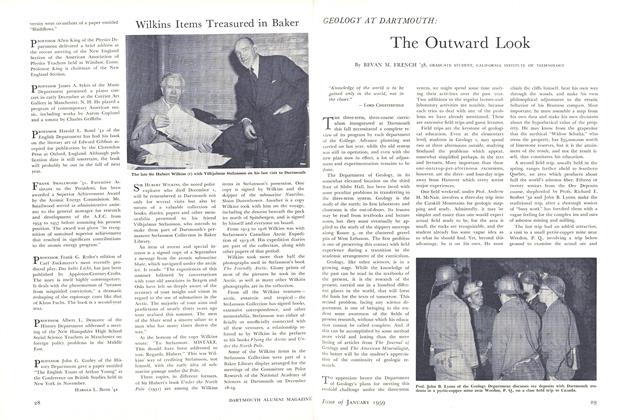

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2007 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Look

JANUARY 1959 By BEVAN M. FRENCH '58 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

MARCH 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

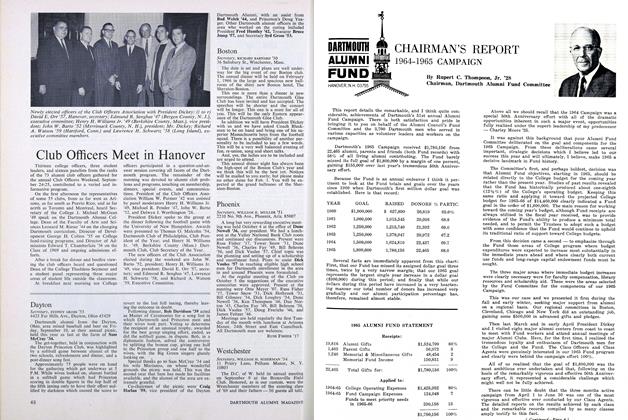

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28