Last April, one of academia's most severe critics turned all of 30. It was the twelfth consecutive birthday the Bombay native had spent away from his family in India. But Dinesh D'Souza '83 hardly had the time or patience for the lamentations that traditionally accompany turning 30. The slightly built thinker appeared to be on the brink of national renown, adding to a precocious career that included two years of studying Dante at Princeton; three years as managing editor of the conservative Heritage Foundation's quarterly Policy Review; two years in the Reagan White House; two years as a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank; two published books; and some 50 free-lance articles.

During the spring his third-and by far his most important-book was published, accompanied by a major author tour. The book, titled Illiberal Education, is an attack on affirmative action in college admissions and on curricular choices offered by the American academy. The response to his arguments has been impressive; the book is being touted by liberal and conservative pundits alike as one of the best to date on the subject, and the first major popular work to undertake an extensive discussion of minority relations in higher education. After a long excerpt was published in The Atlantic, the magazine received more than 200 letters to the editor about the article. Executives at the Free Press, a division of Macmillan, predict that Illiberal Education will succeed Allan Bloom's The Closing of the American Mind as the mustread education book. It has made a good start, reaching number six on the New York Times bestseller list by early June. "It's the story of the year," crows Adam Bellow, D'Souza's editor at Macmillan.

As if instant attention were not enough for this eminence not-so-grise, D'Souza's book even appears to have helped inspire a proposed law. On March 12, Illinois Republican Congressman Henry Hyde backed by the American Civil Liberties Union -introduced the Collegiate Speech Protection Act of 1991, citing Illiberal Education in a briefing paper.

A late bloomer D'Souza is not.

Despite his precocious reputation for subtle wit, he is also known for his readiness to wield a far blunter instrument. The

man's pungent side came out last fall during the campus fracas over a Hitler quote that had been inserted in The Dartmouth Re- view's masthead. D'Souza, incensed over Dartmouth President James O. Freedman's suggestion that the quotation was deliberately planted, called him "the Al Sharpton of academia."

Morton Kondracke '60, senior editor of The New Republic, cites that statement as a sign of D'Souza's lack of political maturity. "He's intellectually strong," Kondracke says. "He doesn't need to call people names."

The incident shows two sides of Dinesh D'Souza: the thoughtful, relentlessly rational thinker, and the no-holds-barred political partisan. For someone who spent the first 17 years of his life on the other side of the world, this seems a peculiarly American approach to politics.

IN ONE IRONIC SENSE, HE IS A TRIUMPH of the academy's increasing accessibility, a trait he criticizes in his book. D'Souza is the very picture of assimilation, a scholar of American politics who speaks without a trace of an Indian accent. And he is an American citizen, as of last October.

In a personal sense, he is an unusual sort of immigrant, coming to the United States not for wealth or freedom or opportunity but out of simple curiosity. D'Souza is the son of a chemical engineer father and a business executive mother, both now retired and living in Bombay. His family counts itself among two Indian minorities: the Roman Catholic church, and the middle class. His ancestors lived in Goa, a southern Indian province that was a Portuguese colony hence his last name. His first name was an act of patriotism by his parents, Allan and Margaret. They called their first son Dinesh, which in Hindustani means "sun god."

The family was nervous when Dinesh announced his intention to study in the United States. "The Indian press had given them an impression that America was full of promiscuity and craziness," he says. Nonetheless, at the beginning of his senior year in high school, he left his country for the first time and went to Patagonia, Arizona, as a Rotary Scholar. He stayed with four American families and attended the local public school. When his American friends began applying to college, he decided on the spur of the moment to do the same. "I ended up picking Dartmouth out of a catalog," he recalls; he matriculated sight unseen. To this day, he wonders whether the Admissions Office didn't give him preferential treatment as a minority. "I remember when I was a freshman here, you know, you wonder, 'Do I belong here? Am I as smart as 0everyone else?'"

But that thought doesn't seem to have held him back. He was elected a freshman representative to the Student Council, became active in the International Students Association, served on the Energy Conservation Commission developing a program under which dormitories were given cash bonuses for saving the most electricity per resident and worked part-time for the College News Service. He studied karate, skied, played tennis, and avoided joining a fraternity. He wrote an unfinished novel, Where ElephantsGo to Die, as an honors thesis. ("I'm interested in writing fiction," he confides, adding playfully: "Some people who disagree with my views think I've started already.")

As a freshman, D'Souza also was a reporter for the daily Dartmouth, becoming "one of three or four of the top freshman reporters," according to Brent West '81, who was executive editor during the first half of D'Souza's freshman year. West became editor in chief late in the spring of 1980 when a political dispute resulted in the ouster of the original editor, Greg Fossedal '81, who then started The Dartmouth Review. West, who is now director of finance for the Bath Iron Works in Maine, remembers D'Souza as a good writer with "motivation and initiative. If something broke in the middle of the day, he was one of the few people you could call." D'Souza moved over to The Review the next year, attracted by the promise of editorial freedom and the space to write more in-depth feature articles. He also liked the tone of the place. "I was with a group of kids who were among the most intellectually challenging and passionate as anyone I met at Dartmouth or since," he says. "We would hold a lot of weird debates on 'Should students be admitted to college on a lottery?' " His zeal for polemics prompted the Jack-O-Lantern to dub him "Distort D'Newsa" a nickname that has followed him to Washington. D'Souza finds the moniker "highly amusing." He kept the Jacko story on his door for weeks. "Actually, some of the Review editors worked on that issue," he says. "There was a temperamental affiliation between the two papers."

His first months at The Review saw the awakening of his conservative beliefs, both in academia and politics. "I would not have developed my interest in the so-called Great Books were it not for the fact that this gaggle of students was avidly reading them in the Review office," says D'Souza. "Some of these kids were actually interested in living out these ideals. I viewed it from the outside with some perplexity and admiration."

He wasn't on the outside of The Review corps for long, however. One of his first acts was to publish a biting attack on Music Professor William Cole and his controversial teaching style. The professor sued D'Souza, along with Reviewers Laura Ingraham '85 and Will Cattan '81. With the help of lawyer Steve Carley '68, the three obtained free legal services from the New York firm of Rogers & Wells. The suit was later dropped. "We played real hardball politics with Dartmouth College," recalls Cattan, who is now a lawyer himself. "Dinesh has never shied away from playing that kind of game when people play it with him and he thinks he's right."

STANDING BEFORE A LESS THAN sympathetic thetic crowd of 70 in 23 Silsby last spring, D'Souza plays a different sort of hardball. It is the kind he plays best: throwing strong assertions, putting a spin on them with witty hyperbole. It is his first public lecture at Dartmouth. Members of The Dartmouth Review sit rapt in the first two rows. Offto the side is English to the side is English Professor Jeffrey Hart, who sits impassively with his wife. The rest of the audience is a mix of the curious and the politely hostile.

D'S ouza presents an outline of his book. He explains that relationships between minorities on college campuses are more strained than ever, and that the worst confrontations occur in the nation's "progressive" institutions, where the most efforts have been made to recruit and accommodate minoritdes. This, he says, bodes ill for America's "experiment" in becoming a multicultural society.

D'Souza asserts that the fault lies with college admissions departments that accept students on the basis of race. He describes the policy at Berkeley, where he says an extreme version of affirmative action sets up different tracks for admission according to race. Because it is far easier for a black or Hispanic than for, say, an Asian to gain admission, less-qualified blacks and Hispanics tend to be admitted. A black who would ordinarily end up at the University of California in Irvine gets accepted at Berkeley as well. He calls this a "ratchetingup effect," in which affirmative action determines the location of a student, not whether he goes to college at all.

Preferentialism in admissions "lives on in life on campus," he continues. Ethnic groups that have been admitted in separate groups stay together after they matriculate. "You can walk on the campuses of some of the most elite schools in America, and what do you see? Embedded segregation—separate enclaves of racism," he says. The result is not integration but embedded hostility, claims D'Souza: "Groups don't resemble so much a smorgasbord as ethnic platoons."

The camps lead to the very opposite of what he calls true diversity. As a student in Bombay, he remembers, he was thrown in with everyone from Communists to theocrats to monarchists. "This was diversity," he tells the crowd. In American higher education, however, racial problems lead to "outright censorship regulations" that punish stigmatizing speech. The term "diversity" has shifted in connotation from a multiplicity of beliefs to "enforcement of conformity."

He says that admissions policies have also led to changes in curricula: "When a student is not as well prepared as his or her peers, it is tempting to believe it's not because I am ill prepared but because Shakespeare is a white male." He describes his own feelings as a freshman just a year away from India: "There were some subjects American history, for example I didn't know much about at all." A political science professor would mention Book Ten of the Federalist Papers and talk about names foreign to D'Souza Publius, Madison. "I felt a sense of confusion and of loss. I looked around me and saw the smug faces of white kids and felt bitterness and hostility."

D'Souza assumes that other "affirmative action students" have similar feelings that make them push to bring their own cultures into the curriculum black studies, Hispanic studies, women's studies, Third World literature and to decry a curriculum devised by white males. The result is a kind of "bizarre cultural Olympics" in which people come to the reading list saying, "How did my guys do?" Through coercion along with its more benign sibling, the changing climate of etiquette so called progressive campuses create "a deeply entrenched racial consciousness," he concludes. "Universities are fighting fire with gasoline."

"I wasn't surprised that the talk went without a hitch," D'Souza says later. "Debate at Dartmouth is more freewheeling and robust than at other schools. But I would argue that a large reason for that is The Review."

USA TODAY SAYS D'SOUZA'S THEORIES "will probably provoke the same kind of heated dialogue [as] Allan Bloom's." Jacob Weisberg, an associate editor at The New Republic who reviewed IlliberalEducation for The Washington Monthly, said he "was surprised at how fair the book is, partly because I'm used to his role as propagandist."

On the other hand, says Weisberg in an interview, "the one thing he says that I think is indefensible is that affirmative action is the cause of racism on these campuses. I don't think he has any evidence that that's the case," other than inferences drawn from anecdotes.

"Of course it's hard to get data because the data probably won't support what he says," counters Harvey Gantt, the Democrat who last fall lost a close U.S. Senate race against North Carolina's Jesse Helms. Gantt, who spoke at the College in a Martin Luther King Day presentation in January, adds that "most schools-particularly Harvard, Dartmouth, Yale give special treatment to children of alumni. And I don't imagine the women and minorities admitted that way drop out at any higher rate."

While D'Souza fails to prove statistically that affirmative action, restrictions on free speech, and racism are causally linked, his often frightening stories clearly have already sparked debate. "It's very anecdotal," concedes Lynne Cheney, chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, who otherwise lauds D'Souza's work. "I think it's a valuable book for people to read....This is not survey research, but that may be the most powerful way to do it."

"His technique is more satirical than analytical, and there's shock value in satire," says John Hennessey, Dartmouth's Third Century Professor Emeritus, who taught at the Tuck School for 30 years. Hennessey discounts the book's scholarly value, observing, "Satire deals with extremes and exaggeration. That's legitimate when used appropriately for literary effect. But it's not a clinical or an analytical treatment of reality."

English Professor Bill Cook adds that critics like D'Souza tend to focus exclusively on the most extreme examples. "It's the Willie Horton approach to education," he says.

IN ALL OF THE BOOK'S 319 PAGES, Dartmouth College barely gets a mention. Why? "First, because I'm too close to that situation," he explains. "Second, the incidents are so bizarre that people wouldn't believe them." D'Souza thinks President Freedman is the main culprit. When asked whether he regrets the "Al Sharpton" attack, D'Souza answers: "No, I don't. It was perfectly justified. Freedman's strategy was to make wild statements overwhelm and drown out his facts....Although Freedman and Sharpton don't wear their hair the same way, a bogus racial incident was manipulated to inflame the community."

Leaders aside, D'Souza professes love for Dartmouth itself. "I'm very fond of the place, and I feel a very deep sense of obligation for my education there." He fondly names Lou Renza, Charlie Wood, Vincent Starzinger, Rose-lea O'Connell, and Jay Parini among his favorite professors, and his book thanks faculty members Henry Terrie, Jeffrey Hart, and Donald Pease for his education. "I would go so far as to say that my quarrels are an expression of my affection for the place though perhaps in an unusual way," says D'Souza.

Still, he says his original interest in politics and, ultimately, his interest in writing Illiberal Education arose in part because "the way in which The Review was treated in the early stages struck me as unfair...! observed a double standard at work that I couldn't fully comprehend." He says that while The Review was attacked by the College for expressing its views, liberal demonstrations and attacks on conservatives have gone virtually unchallenged. D'Souza's nervousness about the College's treatment of himself and other Review people extend to this story: He brought along his own tape recorder for the interviews.

He expects to avoid the academy in his next book, which nonetheless will be a kind of sequel to the last one. It will focus on what America will look like as a multi-racial society, covering the workforce, politics, culture, language, and children's education.

Some of his own admirers may be glad he is staying away from writing about Dartmouth. "I think he's talented and an imaginative right-winger," says Kondracke. "But he's got the problem of The Dartmouth Review in general, and that is that he sometimes doesn't know when to quit."

If D'Souza steers clear of the "Newt Gingrich conservatives, who let their partisanship get the better of them and overcome their good sense," Kondracke maintains, he is "one of those people who in live or ten years could be one of the most important conservative thinkers in the country. He's not there yet."

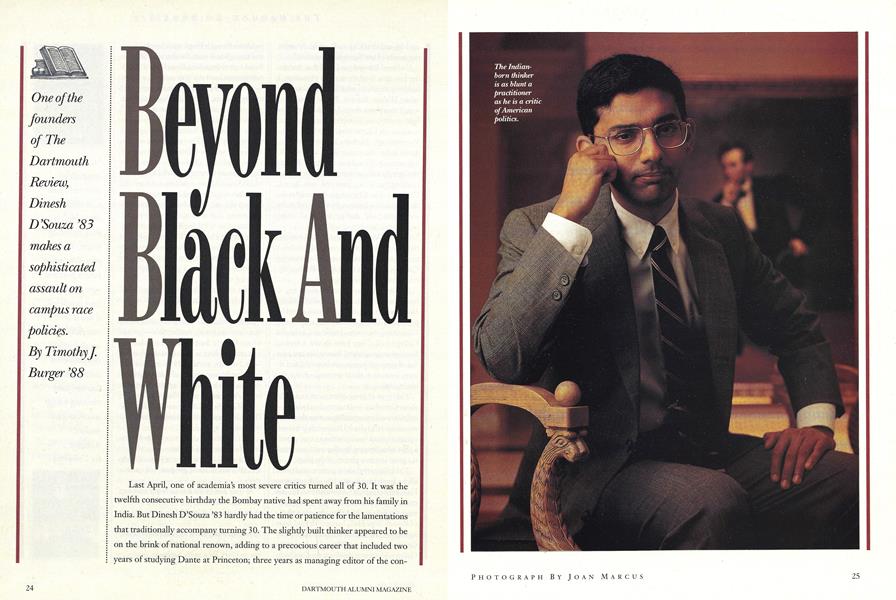

One of thefoundersof TheDartmouthReview,DineshD'Souza '83makes asophisticatedassault oncampus racepolicies.

The Indianborn thinkeris as blunt apractitioneras he is a criticof Americanpolitics.

The next AllanBloom, crowsD'Souza'spublisher.

Mort Kondracke callsD'Souza "a talentedright-winger."

Dinesh was theoldest child amongan Indian rarity a middle-class, Roman Catholic family.

Dinesh and theReviewers played"hardball" withthe College.

Things got nasty when The Review publisheda biting attack on Music Professor WilliamCole. He sued the students for libel.

The Gipper does aphoto op with hisyoung staffer. Dineshhad two years inthe White House.

Despite hisprecociousreputationfor subtle wit,he is alsoknown forhis readinessto wield afar blunterinstrument.

For someonewho spent thefirst 17 yearsof his life onthe other sideof the world,D'Souza's seemsa peculiarlyAmericanapproachto politics.

"It's theWillie Hortonapproach toeducation,"says EnglishProfessorBill Cook.

"You canwalk on thecampuses ofsome of themost eliteschools inAmerica,and whatdo you seelEmbeddedsegregation,"he says.

A former Whitney Campbell UndergraduateIntern with this magazine, Tim Burger is areporter for Roll Call, a newspaper that coversCapitol Hill in Washington, D.C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

June 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureBUG SLAYER

June 1991 By Nancy Freiberg -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

June 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleCOMPUTING AND THE RING OF INVISIBILITY

June 1991 By Professor James Moor, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Awards

June 1991 -

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

June 1991 By James O. Freedman

Timothy J. Burger '88

-

Article

ArticleMilk and Cookies

OCTOBER • 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

December 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticleA Sun-Powered Race Between Two Very Different Schools

December 1988 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticleThe Jungle's Front Man

APRIL 1990 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Article

ArticlePolitics by Design

NOVEMBER 1990 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Cover Story

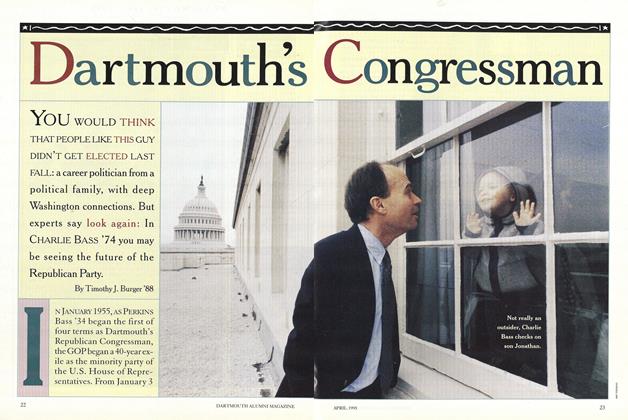

Cover StoryDartmouth's Congressman

April 1995 By Timothy J. Burger '88

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE CAT IN THE HAT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

APRIL 1990 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

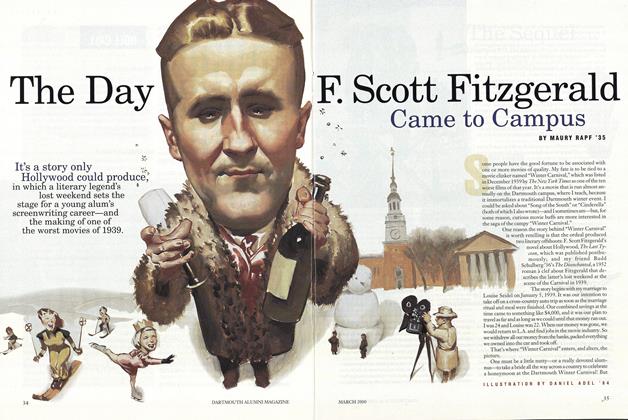

FeatureThe Day F. Scott Fitzgerald Came to Campus

MARCH 2000 By MAURY RAPF ’35 -

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By PAUL G. HOFFMAN