WHY IS IT IMPORTANT for Dartmouth to educate a diverse student body? That question the issue of whom Dartmouth educates goes to the very purpose of the College. And the question of whom American higher education serves is of paramount importance to our nation's future.

Since the Supreme Court's historic decision in Brown v. Board of Education which held that racial segregation in the public schools is unconstitutional we have made decided progress in providing equal opportunities for minorities. The Court's unequivocal affirmation of the equal rights of all citizens 37 years ago was, as Richard Kluger writes in the book SimpleJustice, "nothing short of a reconsecration of American ideals." But the challenge of fully redeeming America's promise of equality the promise set forth in the Declaration of Independence, in the postCivil War amendments to the United States Constitution, and in the inspiring words of Abraham Lincoln still lies before us, and with it, the challenge of fully appreciating the necessary role of education in fulfilling that promise.

THAT CHALLENGE BECOMES MORE PRESSing, as a matter of social justice and economic necessity, as the proportion of minorities in our population grows. By the year 2000 nine years from now no fewer than one-third of all Americans will be members of racial or ethnic minorities. In as many as five states and in more than 50 major cities, members of so-called minority groups will, in fact, constitute a majority.

The 1990 census found that our country's population stood at just under 250 million people. The white population grew by six percent during the 1980s and now constitutes 80.3 percent of the population as a whole.

But the most striking findings of that census are those describing how four of the nation's minority groups all grew significantly faster than the population of whites. More than 12 percent of the country's population is now African-American, an increase of 13.2 percent over a decade before. Persons of Hispanic origin, who can be of any race, are estimated to make up nine percent of the population, an increase of 53 percent. Asian-Americans constitute almost three percent of the population, an increase of 107.8 percent over ten years. And Native Americans compose nearly one percent of the population, up 37.9 percent during the past decade.

In short, the racial composition of our nation changed more rapidly between 1980 and 1990 than at any other time in this century. To those who live in northern New England these changes are less evident, on a daily basis, than they are to those who live elsewhere. Indeed, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont contain the highest proportion of whites in the country in excess of 98 percent. But the homogeneous character of the population in northern New England does not, of course, mean and should not be allowed to mean that Dartmouth can ignore the drama tic changes in the nature of our country's general population.

Dartmouth is a national and even international institution, and it must serve a national and international student population. The knottiest problems of today and tomorroware not just regional in scope but national and international in character, and Dartmouth must contribute to American society its share of outstanding leaders and dedicated citizens who can respond to these problems on their own terms during the challenging decades ahead.

The striking demographic changes of the eighties will have significant consequences for the nation's public school systems and for Dartmouth's future applicant pool. By the year 2000, one-third of all school-age children will be minorities. These developments will also have significant consequences for the nation's work force. By the year 2000, members of minority groups will compose approximately 20 percent of the national work force; in many cities and states that percentage will be substantially higher. At the same time, unemployment rates for African-Americans and Hispanics are, and will predictably continue to be, more than double those for whites.

These two facts high population growth and high unemployment rates for minorities make it clear that American society must be more effective in the future than it has been in the past in providing educational opportunity for minority citizens. Unless this country learns to take fullest advantage of the talents of all its citizens, we will fail to meet our own aspirations, and we will pay a high price in the continuing political and economic competition with other nations, particularly those of Southeast Asia and of the European Economic Community.

The alternative to an America in which all its members share in the opportunities and security that an education brings is, as Benjamin Disraeli wrote in his novel Sybil, two nations "as ignorant of each other's habits, thoughts and feelings as if they were inhabitants of different planets."

SINCE AT LEAST THE time of brown v. Board of Education, it has been clear that educational opportunity is the single most important element in achieving economic advancement and fulfilling one's personal promise. As the Supreme Court stated in Brown, education "is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education."

For the reasons outlined in Chief Justice Earl Warren's unanimous opinion, American colleges and universities have committed themselves to seeking out the widest pool of talent from among the nation's youth. The goal is to strengthen minority representation in their student bodies and thereby to serve the ends of social justice and educational quality.

From its very beginnings as a college established to educate Native American youth and others, Dartmouth has had a unique tradition of educating minorities. Dartmouth's modern commitment to diversity date's not from my administration, nor from that of my predecessor, nor from that of his predecessor, but from the presidency of John Sloan Dickey '29. It was in 1964 that Dartmouth helped to found the successful minority outreach effort, A Better Chance (ABC). It was in 1968 that the Report of the Trustees' Committee on Equal Opportunity (known as the McLane Report) firmly committed Dartmouth College to seeking a diverse student body. The first and central recommendation of the McLane Report is this:

"A healthy college student body of the intellectually able should be broadly representative of national patterns of distribution based on race, religion, social and economic status, and other factors. Dartmouth is a national institution and, therefore, in the long run should attempt to achieve this goal.

"This goal is not easily reached....Because our American system has worked imperfectly, disproportionate numbers of some minority groups are found in lower social and economic groups. It is for this reason that the pool of applicants available to our Admissions Committee will not, without special Dartmouth initiatives, become truly representative of our society truly national."

President Dickey personally felt strongly about this issue. In his convocation address at the University of Toronto in June 1969, he identified "racial travail" as the "number one item on the agenda of the nation" and stated: "Canadians and Americans face the unprecedentedly urgent and massive educational task of re-educating their respective societies in the ways of honest-to-God accommodation, mutual respect of differences and, above all, of effective equality in opportunity in national life."

The nation's changing demographics mean that effective leadership in this country will require many more national leaders from minority groups leaders in politics and public policy, in academia and the sciences, in culture and the arts, and in business and the professions. Dartmouth has as its purpose today as it always has the preparation of students for positions of national leadership. If we fail to prepare young men and women who are minorities for positions of leadership, we fail in an obligation that Dartmouth has embraced and undertaken from its very beginning.

This obligation is best described as a commitment to diversity. It is clear that there is substantial educational advantage to all our students, as well as to our faculty, from exposure to the knowledge, the experiences, the talents, and the perspectives of men and women of different races, nationalities, religions, and economic circumstances. As President Hopkins once said, "An undergraduate gets a considerable part of his education from association with his fellow students, and the more broadly representative your undergraduate body, why, the better your educational process."

Students from minority communities bring perspectives to the discussion of national problems, to the reading of literature, to the understanding of history, that are very different from those of other students. And, so I told the faculty last fall, "It is persons least like ourselves who often teach us most about ourselves. They challenge us to examine what we have uncritically assumed to be true and raise our eyes to wider horizons. As Ralph Waldo Emerson meant when he wrote in his Journal, 'I pay the schoolmaster, but 'tis the schoolboys that educate my son.'"

A commitment to diversity to educating able students from all quarters of our society means much more, however, than a commitment to racial diversity. It means a commitment to geographical, intellectual, and economic diversity. It means seeking students from a broad range of communities, from Kodiak, Alaska, to Staten Island, New York; from Errol, New Hampshire, to East Los Angeles, California. It means creating a pluralism of persons and points of view. It means encouraging unconventional approaches and unfashionable stances toward enduring and intractable questions.

It means opening up our students' minds and our community's spirit to a symphony of different persons, different cultures, different traditions, and different languages. It means, preeminently, pursuing differences and otherness in all of their varied dimensions.

Difference sometimes means conflict. But conflict can be a source of creativity and growth if it is acknowledged with candor and examined with care. When people who are very different from one another must live and work together, tolerance and civility are the only hopes for peace. How we deal with our differences as Americans, how we nurture our shared bonds, will in large part determine the future character of Dartmouth, of our society, and of our country.

Dartmouth has always sought to create a diverse student body with poets, athletes, and trombone players; actors, debaters, and butterfly collectors; young people of talent, ambition, and idealism. It has long recognized that:, educationally, we simply cannot have a campus made up entirely of people who are very much like each other. Our commitment to diversity is a commitment to educational excellence. Every student whom Dartmouth accepts has fully earned a place within the student body.

A LARGE PART of Dartmouth's commitment to assembling a diverse educational community and certainly the most expensive part is ensuring that a Dartmouth education is available to every qualified student, regardless of family economic circumstances. Dartmouth has a moral obligation and civic responsibility to do all it can to make the benefits of a Dartmouth education available to qualified students regardless of financial need.

As the economic gulf between rich and poor has widened in the United States, this commitment has assumed greater importance. And in seeking to assemble what President Hopkins called "an aristocracy of brains, made up of men [and now women] intellectually alert and intellectually eager," Dartmouth simply cannot afford to limit itself only to those applicants who can afford to pay.

During the last academic year, 35 percent of the Dartmouth student body was receiving scholarship assistance, totaling $14.7 million. The average scholarship was $9,748. Put another way, 65 percent of Dartmouth families had it within their means (albeit with some sacrifice) to pay the fall cost of $22,000 annually for education. This level of affluence is certainly not representative of the national population.

As the cost of a college education escalates, Dartmouth, like other selective colleges, increasingly runs the risk of drawing its students from the two ends of the economic spectrum from families in the lowest income brackets, for whom scholarship assistance is most readily available, and from families in the highest income brackets, for whom scholarship assistance is not necessary.

The losers in such a scenario will be students from middle-income families not poor enough to qualify for significant financial aid awards, not affluent enough to pay the entire bill themselves, and often not aware that grant assistance is available for families earning as much as $50,000 to $60,000 a year. A recent study has found that middle-income families tend to overestimate the cost of a private college education by about $3,000. Even if colleges succeeded in dispelling these misconceptions, the pressure on scholarship funds is only too real.

Last year at Dartmouth non-minority American students, who constituted 76 percent of the student body, received 51 percent of Dartmouth's scholarship grants. Minority students and international students, who composed 24 percent of the student body, received 49 percent of scholarship grants. Thus, racial minorities received a greater percentage of the scholarship aid than they constituted in the student body. The reason is plain: racial minorities in this country are more likely to need financial aid. Meeting that need constitutes simple justice and good sense for an institution dedicated to equal educational opportunity.

I have heard it suggested that, in these days of constrained resources, Dartmouth may not be able to afford to continue its commitment to need-blind admissions or the "luxury" of directing a significant portion of its endowment to scholarships. I reject that suggestion. It is important to remember that tuition covers only a little more than half of the real cost of a Dartmouth education. This means that, in effect, every student at Dartmouth including those paying full tuition receives a substantial scholarship or subsidy. The difference between tuition payments and the overall cost of a Dartmouth education is, in every instance, made up from endowment income, gifts, and other sources. And, so, the issue is not whether the College should continue to dedicate a significant portion of its resources to scholarships, but rather how large each student's subsidy should be.

I HAVE ALSO HEARD IT suggested that a commitment to diversity means a commitment to quotas. This is not the case. Dartmouth does not use quotas in its admission process. What it does do and it does so aggressively is to seek out and admit outstanding students from a broad range of backgrounds. Our recruitment efforts include targeted mailings to students, special publications, on-campus programs for prospective students and secondaryschool counselors, visits to urban high schools, and the very crucial personal participation of minority alumni.

Making Dartmouth more diverse does, of course, mean that the composition of our undergraduate classes has changed somewhat. African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and international students make up 23 percent of Dartmouth's student body today, compared with 12 percent in the class of 1984.

That eleven-percent increase reflects the fact that during the past half-dozen years the Hispanic population at Dartmouth grew from zero to three percent, the Asian- American population from three to seven percent, and the Native-American population from two to three percent. At the same time, the African-American population fell from eight percent to six percent.

Those of us in higher education who are committed to the education of minority students are often asked whether African-American and other minority students are admitted to the student body in preference to white students of allegedly greater ability. The question disregards the significant subtleties of assessing ability and promise as if colleges and universities have ever regarded ability and promise as ascertainable by SAT scores alone; as if we should equate the grades and test scores of students from among the weakest school systems in the country with those of students from the strongest; as if motivation, intellectual curiosity, and a history of availing oneself of what opportunities one does have should count for naught; as if colleges and universities had never followed a practice of admitting many students (whether they be athletes, musicians, or children of alumni) because of the special qualities they bring here.

The question also ignores the incontestable fact, as Lyndon B. Johnson said at Howard University in 1965, that "ability is not just the product of birth. Ability is stretched or stunted by the family you live with, and the neighborhood you live in, by the school you go to and the poverty or richness of your surroundings. It is the product of a hundred unseen forces playing upon the infant, the child, and the man."

Moreover, the question avoids the fact that the preferential treatment that Dartmouth's admissions process gives to children of alumni effectively puts minorities at a competitive disadvantage, since the vast majority of alumni with college-age children are white.

There are those who argue that colleges and universities ought not consider race at all in the admissions process indeed, that it may be racist to do so. I vigorously reject that argument. Regrettably, racial prejudice and racial discrimination still disfigure American life. Sadly, racial status still limits opportunity in American society. It is therefore inappropriate, in my view, to describe as racist those very admissions practices that would take account of race for the precise purpose of redressing the historic consequences of racial discrimination. Justice Harry A. Blackmun, in his opinion in the Bakke case, spoke wisely when he commerited: "[I]t would be impossible to arrange an affirmative-action program in a racially neutral way and have it successful, To ask that this be so is to demand the impossible. In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently"

It would be ironic, indeed, as Justice Blackmun further observed, to interpret the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which was adopted immediately after the Civil War in order to achieve equality for emancipated Negroes, in a manner that would "perpetuate racial supremacy."

Educators are called upon increasingly to explain the causes of racial tension on American campuses. Why, we are asked, cannot minority students and white students get along better with each other? Why do African- Americans and other minority students sometimes seek to remain by themselves, especially in the dining halls?

In thin Icing about these questions, we need to remind ourselves that minority students are not the only ones who in fact are apt to sit together, in separate groups, at the same dining tables. So do football players and engineering majors and graduates of the same preparatory schools. No one notices when these groups of students sit together or if they do, no one seems to find such con duct unusual. But when minority students choose to sit together doubtless for much the same reasons as many other students do some people do notice and some people do react negatively. My point is simply that we should use a single standard in judging the complex motivations of friendship and the need for social support that animate student behavior.

Moreover, the questions I have cited assume, erroneously, that efforts to attract minority students have created these social dilemmas. In fact, relations of equality between persons of different races is a relatively new experience in the history of this country. Many of today's students come to college without ever having had sustained interaction with students of different races or different economic backgrounds. Many lack a level of social ease with minorities, which in turn inhibits the ready development of personal relationships. We would be naive to expect these relations, at this point, to be free from friction or tension.

College students today white and black, majority and minority are part of a transitional generation whose members are learning to relate one to another in ways not yet entirely familiar and comfortable, but they are doing so with an earnestness and good faith that in the end will create a far better climate for the achievement of true equality than this country has yet known.

A certain degree of tension on the issue of race relations may actually be a sign of good health for an institution. The challenge is an educational one: to foster learning among students of diverse backgrounds by encouraging discourse, tolerance, civility, and engagement what John Dickey called "honest-to-God accommodation." More than ever before, we all have to live and work with each other. College is the best of those places where we learn to do so. And for all of the occasional points of tension, success stories still far outnumber the moments of friction.

This, then, is not a time to pull back in our efforts to redeem the promise of equality. Rather, it is a time to strive, more patiently and more steadfastly than ever, to learn how to establish a society based upon the practice of equality. It is a time for idealism, not cynicism; for healing, not wounding; for understanding, not indifference.

The efforts to achieve diversity that are currently being made at Dartmouth and on other campuses are an essential part of that learning experience. We need to support them with a vigor and fidelity that reflects their importance to America's future.

Dartmouth'spresidentmakes thecase fordiversity.

"The issueof whomDartmoutheducates goesto the verypurpose ofthe College "

"It is personsleast likeourselves whooften teach usmost aboutourselves."

"A certaindegree oftension onthe issue ofrace relationsmay actuallybe a signof goodhealth for aninstitution."

"Dartmouthis a nationaland eveninternationalinstitution,and it mustserve anational andinternationalstudentpopulation."

"Nine yearsfrom now,no fewerthan one-third of allAmericanswill bemembersof racialor ethnicminorities."

"Unlessthis countrylearns totake fullestadvantageof the talentsof all itscitizens, wewill fail tomeet our ownaspirations."

"Everystudent whomDartmouthaccepts hasfully earneda placewithin thestudent body."

"Thechallengeof fullyredeemingAmerica'spromiseof equalitystill liesbefore us"

This essay is adapted from an address the president gave to the Alumni Council on May 17,the anniversary of the Supreme Court's decisionin Brown v. Board of Education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

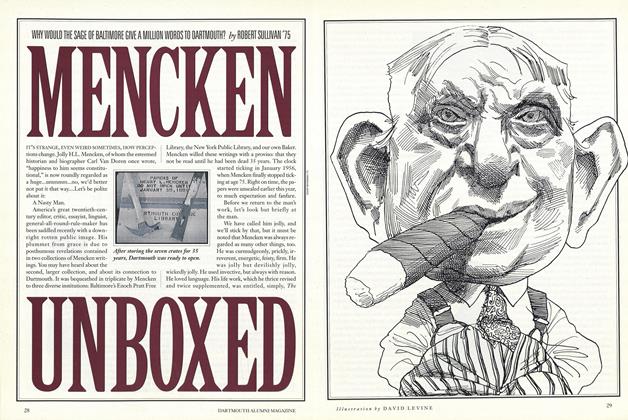

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

October 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

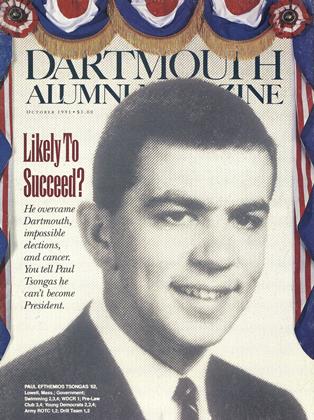

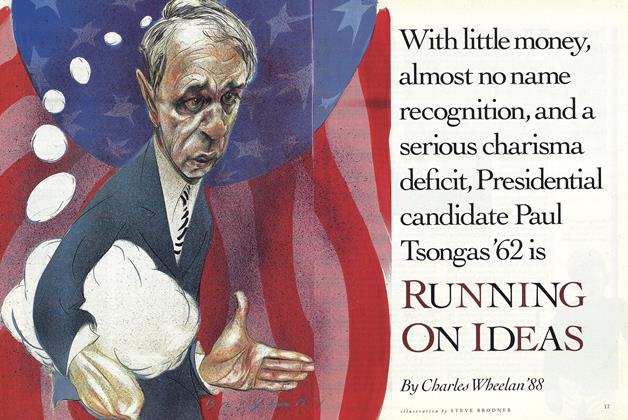

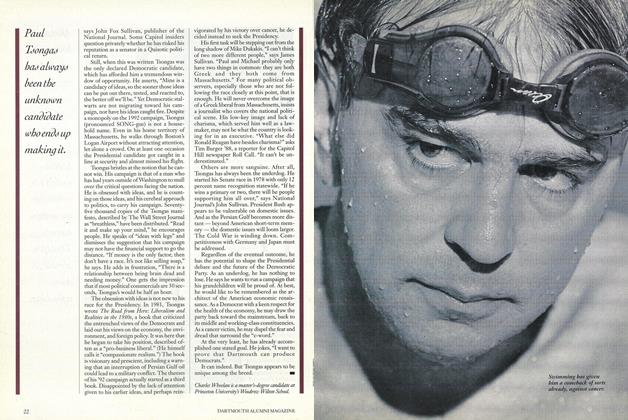

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

October 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Masked Stork

October 1991 By William DeJong '73 -

Feature

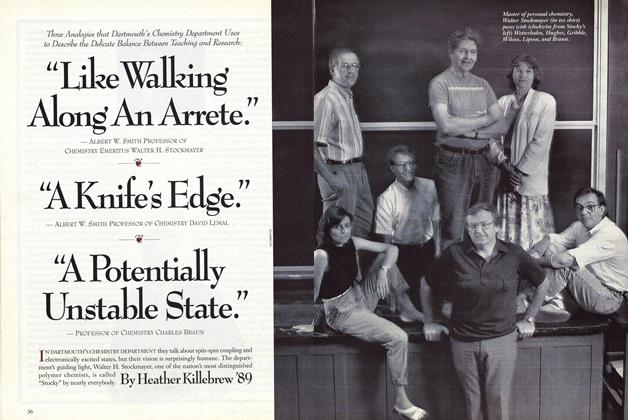

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

October 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

October 1991 By Chuck Young

JAMES O. FREEDMAN

-

Article

ArticleTHE TRANSFORMING POWER OF LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

NOVEMBER 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryGetting Things Right

MARCH 1995 By Donald Goss '53 -

Feature

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Features

FeaturesRising Star

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Feature

FeatureD’Souza’s America

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeaturePublic Policy: The Ordeal of Choices

JANUARY 1971 By William D. Carey