With a mixture of education and high technology C. Everett Koop '37 hopes to reform medicine at its source: the practitioner.

"No one has ever sufficiently appreciated the general practitioner and the sympathy and help he gives folks. These crack specialists, the young scientific fellows, they're so cocksure and so wrapped up in their laboratories that they miss the human element. Except in the case of a few freak diseases that no respectable human being would waste his time having, it's the old doc that keeps a community well, mind and body."Sinclair Lewis, Main Street, 1920

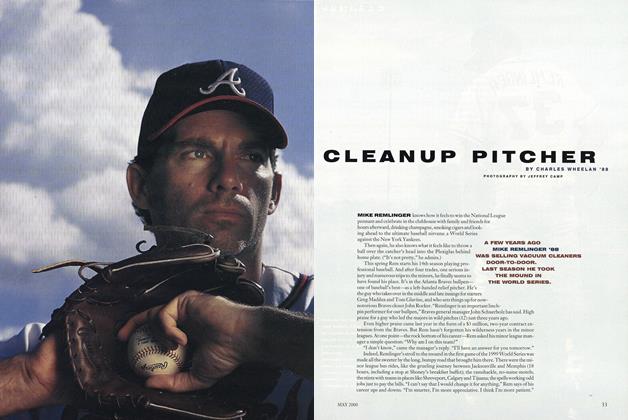

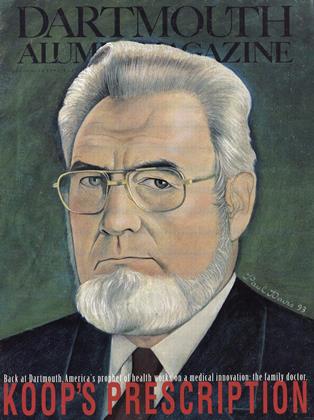

When C. Everett Koop arrived in Washington in 1981 at age 64 to accept the nomination for surgeon general of the United States, an act of Congress was required to lift the age limit and allow him to join the Reagan Administration. Now, a decade later and well after his Dartmouth 50th reunion, Dr. Koop, or "Chick" as he has been familiarly known since his freshman year in Hanover, is embarking on what he describes as his fourth career. After 35 years as one of the nation's preeminent pediatric surgeons, eight years as surgeon general, and a brief spell as a freelance advocate for better public health, Koop has returned to Hanover to join forces with the Dartmouth Medical School and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center to establish the C. Everett Koop Institute. The goal of the Institute and its bearded, avuncular namesake is no less than to shape the way medicine will be practiced in the twenty-first century.

Koop's vision of health care is both futuristic and nostalgic an unlikely hybrid of Marcus Welby and "Star Trek." Koop and his colleagues seek to harness the best of technology and specialized medicine while recapturing the ethos of the family doctor. The cornerstone of Koop's vision is the primary-care physician, a general practitioner who is committed to preventive medicine and the doctor-patient relationship but also able, at the push of a button, to consult with specialists hundreds of miles away using the latest in video and communication technologies. In the long run, Koop would like to fix the current health-care delivery system, in which it is more profitable and prestigious to deliver a pound of cure than an ounce of prevention. As a beginning, the Koop Institute hopes to inspire a higher percentage of Dartmouth Medical School graduates to forego lucrative but overpopulated and overused specialties in favor of general medicine. Koop also wants to imbue future specialists, from neurosurgeons to cardiologists, with a renewed respect for the humanist side of medicine. All the while, C. Everett Koop, America's most recognized health crusader, will use the Institute as a bully pulpit from which he can advocate structural changes in the way the nation practices health.

KOOP IS NO STRANGER TO THE MEDICAL spotlight. When he was appointed surgeon general in 1981, both sides of the political aisle assumed that he would be primarily a mouthpiece for the pro-life Reagan White House. The appointment was one of the most controversial in recent memory. A New York Times editorial branded him "Dr. Unqualified." But the appointment survived, and the surgeon general went on to surprise his detractors. It was Koop who began wearing the military dress uniform as a means to improve both the visibility of the office and the esprit de corps. (The surgeon general is technically an admiral in the Commissioned Corps of the United States Public Health Service.) What the surgeon general lacked in Washington clout (being three administrative levels below a cabinet position), Koop made up for by wielding the bully pulpit. "A thousand people will stop smoking today," he intoned, challenging the powerful tobacco industry. "Their funerals will be held sometime during the next three or four days."

The unique challenge for Koop as surgeon general, however, was AIDS. In the early 1980s, the disease was a medical curiosity, yet unnamed and known only to a handful of scientists. In the end, the surgeon general allied with the liberals and moderates who had so vehemently fought his confirmation in order to mount an aggressive education campaign against the spread of HIV. (His 1988 AIDS mailer a simple but candid discussion of the disease and how to prevent it went out to 107 million households, the largest single mailing in American history.) In an ironic twist, Koop went from being the liberals' "Dr. Unqualified" to being labelled "Dr. Condom" by his former allies on the right.

The complexity of the man and his beliefs is best encapsulated by an incident during his final year as surgeon general. Koop was asked by Time to have his portrait taken by Robert Mapplethorpe. The contrast between the two men is striking. C. Everett Koop is an evangelical Christian who describes the religious right as "people with whom I share the deepest beliefs and values." Mapplethorpe is the photographer whose homoerotic images caused an uproar among conservatives when a traveling exhibit was sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts. Mapplethorpe, who was dying of AIDS, was too ill to travel to Washington to shoot the photo. Instead, Koop flew to New York to enable the bedridden Mapplethorpe to take his portrait. "Judgment is God's business," writes Koop in his autobiography.

His ability to mesh personal belief with medical activism earned him not only visibility but respect. More than anyone else, he is America's family doctor. "He really, in the public's eye, is everyman's physician," says John Duffy, Koop's assistant in Washington and now director of the Koop Institute.

IT IS THAT TRUSTED STATURE THAT KOOP is bringing to the institute that bears his name. Those most immediately affected by the Koop Institute will be the graduates of Dartmouth Medical School. "The Koop Institute is dedicated to health care reform in any way possible, but we're concentrating now on the reform of medical education to achieve that end," says Koop. He and his colleagues feel that medical-school curricula may be institutionalizing the ills that are creeping into the profession. "I think that the current crop of medical students is very altruistic and very idealistic," Koop says. "The problem is that the way medicine is taught these days is very disillusioning to them. By the time they've had all this stuff crammed into them, not had any contact with patients, not had the opportunity to do the things with people that attracted them to medicine, they become disillusioned. And I think a disillusioned student becomes all the things that the public would rather not have in a doctor."

Koop and his colleagues would like to see all students involved in primary care from their first week on campus. Whereas much of medical education takes place in the lab and lecture hall or with the very sickest patients, Dartmouth would like students out in the community where the practice of medicine takes on a wider context and a more varied face. To that end, incoming students are being teamed with needy families in the Upper Valley whom they will advise on health care and related social services. "This might be a family in distress," says Koop. "But it could be a family that is just facing the ordinary vicissitudes of life. Perhaps the lady is pregnant and expecting a baby, in which case that student would learn something about what it means to be of modest means and have another mouth to feed and all the socioeconomic problems that go with that. On the other hand, it might be a very distressed family where there are three or four people who have chronic illnesses. From a humanitarian view you learn certain things about patients and how families operate in the home that you can't ever pick up in an office." Koop and colleagues also hope that this community-medicine program will foster facultystudent interaction as students seek advice from experienced physicians when they encounter the unfamiliar. "Out of that will come some true mentoring situations," says Koop. "That's what we think education is really about."

Under the tutelage of the Koop Institute, Dartmouth medical students also get to teach preventive medicine, the pillar of primary care. Last year the Medical School began a pilot program at Hanover's Bernice Ray Elementary School in which 19 medical students and 25 Ray School teachers collaborated on, and taught, a health curriculum. The "wellness" theme covers low-tech ways to stay healthy, including diet, seat belts, and education about smoking and substance abuse. Twice as many Dartmouth medical students are expected to participate next year as the program branches out into high-school seminars on alcohol, drugs, sex, and tobacco, and pre-school lessons on toothbrushing and other healthful beginnings. The program satisfies the institute's emphasis on prevention and gives medical students experience as the counselors Koop would like them to be. As Institute Director Duffy explains, "We think that what a lot of what physicians do, whether they understand it or not, is teaching. And yet nowhere in their professional education do they ever learn how to teach."

Programs such as these are the means to an explicit goal of the Koop Institute: to inspire a larger percentage of Dartmouth Medical School graduates to become primary care physicians the kind of doctor the nation needs most. "We would like 50 percent of our graduates to go on to those types of careers," says Dr. Joseph O'Donnell, associate dean for student affairs. The current level is 37.5 percent. "Even those who don't, who may go into a sub-specialty or into a research-oriented career, will at least have the skills, values, and attitudes of a generalist," O'Donnell adds. "Everybody gets to that level."

Koop and his peers are acknowledging a phenomenon that economists have long pointed out: a system overladen with specialists gives inadequate attention to preventive medicine and leads to expensive treatment of simple problems. Clearly, specialization has made advanced medical care in America the envy of the world. Koop himself was part of this. He helped create the specialty of pediatric surgery in the late forties. By the end of his surgical career he had separated more than ten sets of Siamese twins using a technique he invented, performed more than 17,000 hernia operations, and operated on individual patients as many as 50 times to correct congenital problems. But Americans all too often are shuttling from allergists to gastroenterologists to otolaryngologists for many problems that a well-trained general practitioner could handle in a single visit. In reclaiming a vital niche for general practitioners, Koop is reminding Americans patients as well as physicians that a lot of human ailments do not require specialist treatment or prices. The ratio of specialists to primary-care physicians in the United States is roughly 70-30, according to Susan Dentzer '77, who covers economic issues for U.S. News and World Report. Germany, which has similar health outcomes, is roughly 70-30 in the other direction.

The Dartmouth Medical School's goal of graduating half its students as generalists runs up against structural barriers far beyond the control of the Koop Institute. The incentive to specialize is in part the product of the American system for compensating care. "Financial rewards are all based on what you do to the patient rather than what you do for the patient," says Duffy. The bill for heart-bypass surgery can reach tens of thousands of dollars; the fee collected by a general practitioner for dispensing advice to eliminate the need for that procedure is a little more than $50 about what a plumber can demand for a house call, notes Koop. To many students graduating with $70,000 to $100,000 of debt, general practice seems financially untenable. Compounding the problem is the lack of prestige generalist practitioners have been accorded by the medical community, despite their need for a broader range of knowledge than their specialized colleagues. Then, too, because general practitioners often work alone or in isolated areas, they may actually have more rigorous schedules. "All of the market forces money, prestige, and quality of life work against people going into primary care," says William Culp, associate dean of the Dartmouth Medical School.

The overabundance of specialists results not only in expensive medicine but possibly unnecessary medicine as well. The Koop Institute has been most interested in Dartmouth epidemiologist John Wennberg's pioneering research on supply-induced demand the idea that an oversupply of doctors and hospital beds may lead to more medical procedures, whether they're necessary or not. Wennberg has challenged the medical profession to gain a scientific understanding of what is effective medicine and what is not by documenting medical outcomes. People assume things work, says Wennberg, when in fact the medical community has only a vague notion of what procedures and treatments are really effective in the long run. Not only do patients suffer from this dearth of knowledge, but, as Duffy notes, prescribing what doesn't work is expensive. At worst, Wennberg and his colleagues estimate that the nation could be wasting a third or more of all health-care expenditures on medicine of dubious value.

The Koop Institute hopes to build on Wennberg's work in several respects. This fall the Medical School's Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences launched a graduate program to train people in "outcomes research." Similarly, changes in the Medical School curriculum will reflect the importance of providing more complete information to patients about the risks and outcomes of various procedures. Seldom is there a "right" treatment, says Wennberg, so doctors should work with their patients to find the optimal solution on a case-by-case basis. (Of course, if Koop has his way, family doctors will encourage their patients to lose weight, quit smoking, and thereby avoid many surgical procedures altogether.)

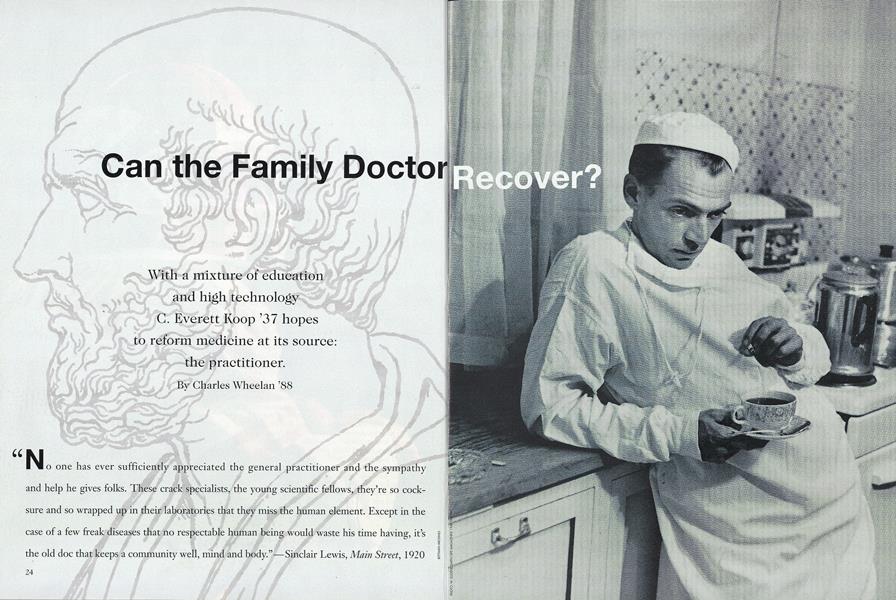

The call for a return to working with patients goes to the very heart of health care. Koop and his colleagues feel that in the rush toward specialization, an essential element of healing the doctor-patient relationship has been sacrificed somewhere along the way. Whereas the physician of old would linger over a cup of coffee after a house call, it is now possible to have brain surgery and never see your doctor again. Duffy blames society for embracing science as a medical panacea. The human issues were lost in the hubris of penicillin, the Salk vaccine, multiple organ transplants, and other seeming miracles of medicine, he says. "The attitude became 'you're the patient, I'm the doctor.' You come with a problem, all I have to do is diagnose you, get [the problem] titled, find the right science and technology, apply it to that name, and you go out the door a cured patient." According to Dartmouth-Hitchcock physician Robert Charman '57, author of AtRisk: Can the Doctor-Patient Relationship Survive in a High-Tech World?, patients' confidence in their doctors is crucial to healing, but that does not entitle physicians to unquestioned authority.

An early run-in Koop had with such distant and authoritarian doctoring profoundly shaped his ideas of what healing should be. Ironically, it happened during his years at Dartmouth. An avid outdoorsman, Koop was convinced by his fellow fraternity members to represent them in the 1935 Winter Carnival intramural ski-jumping competition. More bold than skilled, the Brooklyn native flew off the icy ramp, did a half-flip, and landed on his back. The accident fractured his neck and caused a spinal concussion that left him temporarily paralyzed. He says of his recovery, "I learned what it was like to lie alone and afraid in a hospital bed, not knowing what the future held, afraid to find out, more afraid not to know. I resolved that when I finally became a doctor, I would not let my patients lie in fear caused by an inattentive physician." Nearly 50 years later his Koop Institute is dedicated to reestablishing the doctor-patient relationship to what it should be and to the glory it deserves for neurosurgeons as well as family doctors. Says Koop: "We'd like [all doctors] to think like family practitioners used to. That means putting their patient first, being good communicators, and having an humanitarian core to whatever they do."

While in many ways the Koop Institute looks back to earlier days to recapture the human face of medicine, it looks forward in one major respect: communications technology. Supercomputers and fiberoptic cables are what will enable the Marcus Welbys of the future to make house calls with a twenty-first-century twist (see the sidebar on page 26). Already physicians at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center are conducting video consultations via computer link-ups. Koop and his colleagues are trying to convince the wider medical profession that they have seen the future, and this is it. Says Koop, "We have already demonstrated to Ira Magaziner and other people from the White House how much this could be a major cog in whatever they do for rural health." Not only will data highways ease the isolation of many primary-care physicians, but computer links will reduce costs and accommodate patients by allowing primary-care providers to perform more procedures with the guidance of specialists across the nation. Duffy asserts that family doctors and their colleagues "will be in a position in their offices to deliver 90 percent of all the health-care needs and requirements of the patient as opposed to today when they can only deliver ten to 15 percent." In the case of Dartmouth, patients who today drive for hours from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center may never have to leave home.

Obviously the Koop Institute alone will not change a health-care system that consumes roughly one dollar of every eight spent. Koop himself is most closely associated with the political party that left the White House last January. He is also noted more as a physician and academic than as a policy analyst. But when it comes to influence with the public and medical profession, Koop remains unmatched—as the Clintons acknowledged in recruiting him to pitch their long-awaited reform plan to a wary medical establishment. Koop recognizes that medical schools and physicians have to be won over. "The process needs people like him to show that general practitioners can have inspiring and challenging careers," says U.S. News and World Report's Dentzer. Just before his two terms as surgeon general ended in 1989, Koop told a reporter, "Sometime five years or more from now I'd like one of you to say, 'You know, after he ceased to be surgeon general, he continued to be the health conscience of America.'"

Clearly, this doctor has not yet finished caring for the nation's health.

CHARLES EVERETT KOOP 489 Rugby Rd.. Brooklyn, N. Y. FLATBUSH HIGH SCHOOL. ZoologyA ∑ φ. Zeta Alpha Phi, President.

Koop would like to fix the current health-care delivery system, in which it is more profitable and prestigious to deliver a pound of cure than an ounce of prevention.

He went from being labeled "Dr. Unqualified"by his liberal opponents to being blasted as"Dr. Condom" by his former allies on the right.

A frequent contributor, Charles Wheelan '88 is a doctoralcandidate in public policy at the University of Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

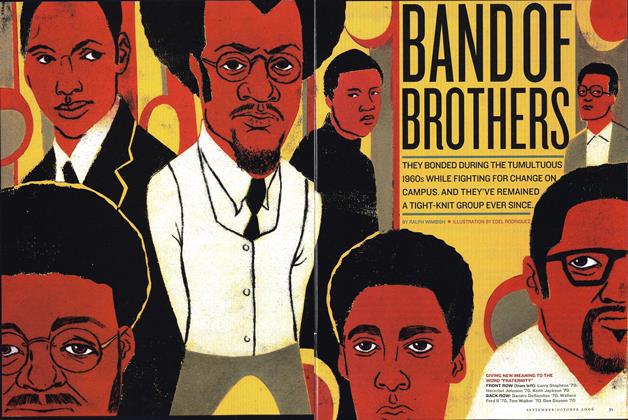

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

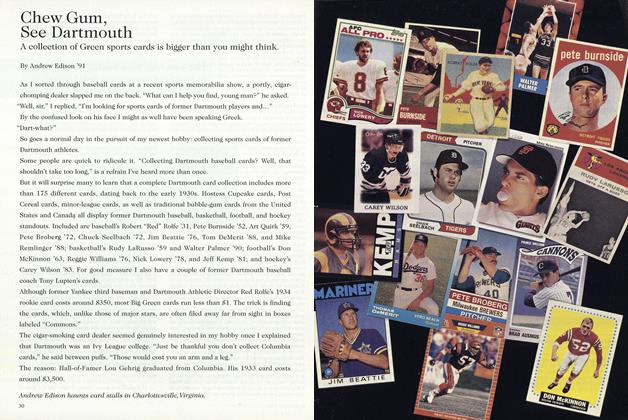

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleAdvancing the Human Condition

November 1993 By James O. Freedman