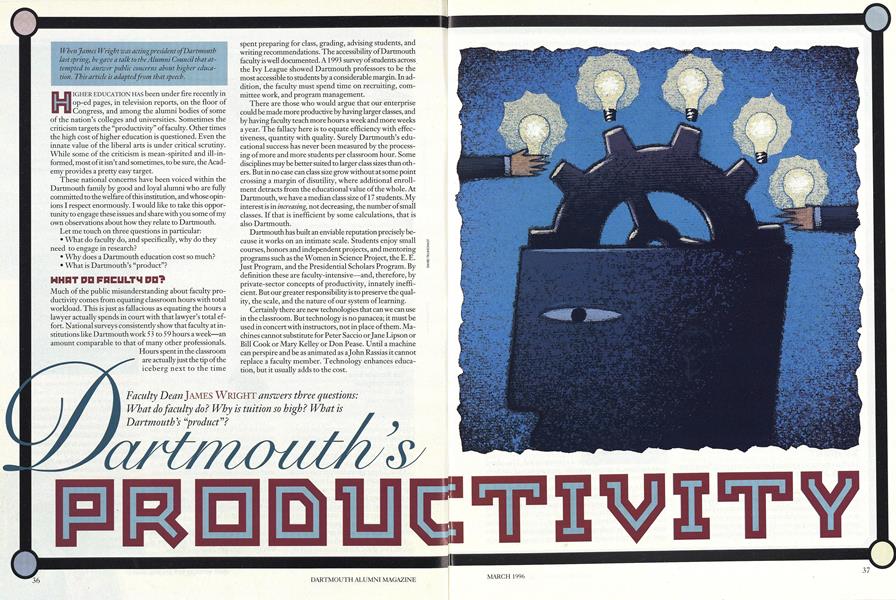

Faculty Dean James Wright answers three questions:What do faculty do? Why is tuition so high? What isDartmouth's "product"? ,

HIGHER EDUCATION HAS been under fire recently in op-ed pages, in television reports, on the floor of Congress, and among the alumni bodies of some of the nation's colleges and universities. Sometimes the criticism targets the "productivity" of faculty. Other times the high cost of higher education is questioned. Even the innate value of the liberal arts is under critical scrutiny. While some of the criticism is mean-spirited and ill-informed, most of it isn't and sometimes, to be sure, the Academy provides a pretty easy target.

These national concerns have been voiced within the Dartmouth family by good and loyal alumni who are fully committed to the welfare of this institution, and whose opinions I respect enormously. I would like to take this opportunity to engage these issues and share with you some of my own observations about how they relate to Dartmouth.

Let me touch on three questions in particular: • What do faculty do, and specifically, why do they need to engage in research?

• Why does a Dartmouth education cost so much?

• What is Dartmouth's "product"?

WHAT DO FACULTY DO?

Much of the public misunderstanding about faculty productivity comes from equating classroom hours with total workload. This is just as fallacious as equating the hours a lawyer actually spends in court with that lawyer's total effort. National surveys consistently show that faculty at institutions like Dartmouth work 53 to 59 hours a week—an amount comparable to that of many other professionals. Hours spent in the classroom are actually just the tip of the iceberg next to the time spent preparing for class, grading, advising students, and writing recommendations. The accessibility of Dartmouth faculty is well documented. A 1993 survey of students across the Ivy League showed Dartmouth professors to be the most accessible to students by a considerable margin. In addition, the faculty must spend time on recruiting, committee work, and program management.

There are those who would argue that our enterprise could be made more productive by having larger classes, and by having faculty teach more hours a week and more weeks a year. The fallacy here is to equate efficiency with effectiveness, quantity with quality. Surely Dartmouth's educational success has never been measured by the processing of more and more students per classroom hour. Some disciplines may be better suited to larger class sizes than others. Butin no case can class size grow without at some point crossing a margin of disutility, where additional enrollment detracts from the educational value of the whole. At Dartmouth, we have a median class size of 17 students. My interest is in increasing, not decreasing, the number of small classes. If that is inefficient by some calculations, that is also Dartmouth.

Dartmouth has built an enviable reputation precisely because it works on an intimate scale. Students enjoy small courses, honors and independent projects, and mentoring programs such as the Women in Science Project, the E. E. Just Program, and the Presidential Scholars Program. By definition these are faculty-intensive—and, therefore, by private-sector concepts of productivity, innately inefficient. But our greater responsibility is to preserve the quality, the scale, and the nature of our system of learning.

Certainly there are new technologies that can we can use in the classroom. But technology is no panacea; it must be used in concert with instructors, not in place of them. Machines cannot substitute for Peter Saccio or Jane Lipson or Bill Cook or Mary Kelley or Don Pease. Until a machine can perspire and be as animated as a John Rassias it cannot replace a faculty member. Technology enhances education, but it usually adds to the cost.

In addition to their work with students, our faculty also work on their own research. To some critics, overemphasis on research is seen as the villain that shunts good teaching aside. I can tell you that research contributes significantly to the quality of the classroom experience. Professors are renewed and remain vital, excited teachers by being engaged in the forefront of their discipline. Research is absolutely essential for up-to-date, inspiring teaching.

Can you imagine a law professor who didn't keep up with the development of constitutional law since graduating from law school? Can you imagine going to a physician whose understanding of medicine hasn't changed in five years? Why would we expect professional competence that is any less upto-date from professors, from those whom we have entrusted with the education of our next generation of leaders? Professors at leading institutions have to do a lot more than that to stay current. Indeed they help define what is current in their respective fields. At Dartmouth, faculty research is not an individual indulgence, a perquisite of employment. It is an institutional priority. The intellectual vitality it sustains finally explains why the best students come here.

Does anyone suppose that mere chance attracts top-quality students to Hanover year after year? The exceptional admissions results for the class of 1999 are just the latest proof that Dartmouth is seen as the school of choice by a substantial number of this country's most promising students. They want the opportunity to work in top-notch research labs, to work with faculty who are on the cutting edge in their fields, to know their professors and have their professors know them.

Nor is it any accident that we recruit an exceptional faculty. We compete against some tough rivals—and we compete exceptionally well. Of the assistant professors hired over the past eight years, more than 80 percent have been our first choices, and many of the remainder have been close seconds. This accomplishment is testimony to the great attraction a career at Dartmouth offers some of the nation's best young teacher-scholars.

Many of the nation's 2,000 colleges have faculties who teach more hours and more students in bigger classes, and engage in less research, than Dartmouth's faculty. But these are not the colleges and universities that attract students and faculty of Dartmouth's caliber. Dartmouth is a center of learning, not one of recitation; a place more intrigued by the unknown than by the known.

WHY IS THE COST OF A DARTMOUTH EDUCRTION SO HIGH?

Higher education continues to increase in price faster than inflation. What drives the growth? Let's look at our cost structure.

As I've already indicated, higher education is labor-intensive. Sixty percent of the College's cost is in salaries and benefits. In the national debate about the costs of higher education, faculty compensation is sometimes pointed to as a root cause of spiraling costs. However, other professions with similar years of education have been increasing their labor costs faster. For instance, in 1979, lawyers earned 46 percentmore than professors; by 1993 that earning gap had widened to 70 percent. I came here in 1969 at a salary of $ 10,000 per year. Starting faculty, brilliant young scholars with Ph.D.s, will earn $3 8,000 in the next academic year. You judge if we're paying too much.

Salaries and benefits are lower at Dartmouth than at competing schools. For instance, faculty compensation is at or near the bottom of our 15-school comparison group. Administrative compensation is also lagging. I don't take pride in either fact—I'm concerned that our salaries are too low—but my point here is that Dartmouth's salary expenditures are not out of control.

Many critics cite administrative bloat as an inflation factor. And surely there is no doubt that we provide more extracurricular and athletic opportunities than we did 40 years ago; more services; more counseling. So does our competition. In fact, at Dartmouth we have reduced the number and the rate of growth of administration in the last several years.

There are other causes for spiraling costs. As with other employers, we are affected by the rising costs of benefits, particularly medical insurance. Like many employers, we have trimmed our benefits package, but costs still go up. In a labor-intensive organization these increases are especially painful.

Supporting teaching and research (particularly in the sciences) requires a costly investment in facilities and equipment. State-of-the-art equipment is particularly expensive; its price rises far faster than the CPI—and by definition it becomes obsolete quickly. Similarly, state-of-the-art facilities—such as the new Burke chemistry building and the Sudikoff computer-science center—stretch our operation and maintenance expenses. The remarkable range of health and safety regulations that cover undergraduate laboratory facilities is not cheap.

We are affected significantly by international economic fluctuations, especially in the value of the dollar. The 40 offcampus international programs we offer every year, paid in 16 different currencies, put us at a grave disadvantage when the dollar is weak, as it has been in recent years. Similarly, library materials are also costly, particularly those bought on the international market—and they are an increasing proportion of these materials.

Finally, we come to the cost of financial aid. This, along with facilities, is the most rapidly growing part of our budget. Dartmouth is one of about a dozen schools in the country with a commitment to need-blind admissions and to helping all admitted students and their families meet our costs. Dartmouth is accessible not just to the very wealthy, but also to talented students from all social circumstances, the middle class as well as the very poor. To be a school that educates future leaders requires a student body that contains some of the most promising young men and women in the country (and indeed the world), representing the whole spectrum of economic circumstance. That's the face of today's Dartmouth. We are committed to keep it.

To meet these costs of compensation, facilities, equipment, and financial aid, we have limited revenue options: tuition, endowment income, gifts, federal support. Of these, federal financial aid is down dramatically, even as we have been more successful in competing for federal research and training grants. And these funds likely will soon become more scarce. Annual giving to the Alumni Fund is essentially flat in uninflated dollars. Our endowment, while very well managed, is smaller than those of our competitorsboth in absolute numbers and when measured as endowment per student. Within the country's 100 largest endowments, Dartmouth ranks 22nd in the critical measure of endowment per student. We are behind not just Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and Stanford—we also fail to measure up to Amherst, Williams, Swarthmore, Wellesley, and Smith. Our exceptional results are therefore not based on exceptional wealth.

Finally, tuition is our major source of unrestricted revenue. Every effort has been made by this administration and the Trustees to be sensitive to the rate of tuition growth. Our tuition remains at about the middle of the Ivy League.

Of course there are places where economies of scale can be had: in purchasing, in merging administrative offices, in consolidating and eliminating functions, and even in modes of teaching. We have accomplished much in these areas, and we will continue to look for opportunities to do more.

My conclusion is that the College today is remarkably strong and financially sound. And if we achieve a lot, we achieve it with limited resources. By its industry's standards, Dartmouth runs a tight ship. Let us reflect a bit on our history over the last 25 years:

• With coeducation we increased the student body by 30 percent and the tenure-track faculty by 17 percent.

• We expanded significantly our off-campus programs. (This, along with a year-round calendar, means we have expanded dramatically the time and space of our operation.)

• We have maintained well—even as we have expanded—our physical plant.

And during this period we have clearly improved qualitatively by every measurable criterion. In sum, our record through the Kemeny, McLaughlin, and Freedman years is one of prudent management and of efficient use of our resources. That is why we have an Aaa bond rating from Moody's.

Of course our tuition is high—and our education is still a bargain. Ask prospective students and their families. They apply to Dartmouth in increasing numbers even though there are very good colleges and universities that cost less. Being excellent is more expensive than being very good.

Ask the marketplace whether the price of a college education in general is worth it. The disparity has widened between the earning capacity of college graduates and that of non-college graduates.

This discussion of productivity begs the question:

WHAT IS DHRTMOUTH'S PRODUCT?

In a sense, John Sloan Dickey gave us the answer. As he reminded us every fall, "Our business is learning." Learningour product at Dartmouth—is not merely the passive transmission of accumulated knowledge but an active engagement in the process of discovery and creation. Our libraries and laboratories, our galleries and studios, our classrooms and offices, our off-campus academic sites resonate with the fall range of all that human beings can know and make. The business of learning is about perspective, about thinking critically and clearly, about expressing and defending ideas, about coming to understand cultures and attitudes and times that are different from our own. About understanding the remarkable physical world in which we live.

How do we measure these things? How do we assess our effectiveness? Surely not with a simple post-baccalaureate test. We are educating for a lifetime. Ask the 50-year reunion class, the 25-year reunion class, about the value of a Dartmouth education. I suggest they will not talk about specific facts learned or about dollars earned, important as they are.

Clearly our most visible product is our students, and by every measure they are satisfied with the education they receive. A 1993 survey of Ivy students showed that Dartmouth's were significantly more enthusiastic about their choice of school than their counterparts. Is a Dartmouth education worth it? Ask them.

Alumni are a product of Dartmouth. In the contributions you make to your profession and your community, you affirm the value of your education. Is Dartmouth worth it to you? A 1994 survey of alumni indicated that 87 percent would choose Dartmouth again.

A Dartmouth diploma is not a tangible thing, like a car. It represents a collection of subtle and not-so-subtle skills acquired—a character shaped, a mind formed, and an intellectual habit fixed. It is my hope that Dartmouth will, through the words and deeds of many people—including alumni as well as faculty and administrators—instill and nurture in its students a habit of mind, a THOUGHT fulness, and a lifelong appetite for learning that will shape lives as responsible and productive citizens.

All we can hope for any of our graduates is that they meetand enjoy—the challenges of their lives. That they feel a responsibility for the world in which they live. This is our product, inefficiently delivered, perhaps, and also imperfectly measured by entire lifetimes. But we regularly meet the test of time. Come to reunions and you will know this. Here our graduates celebrate their own experience and worry about that of current students. It has always been so.

Next time you're in Hanover, meet some students, sit in on a class, talk to some faculty, take the measure of the place. I invite you to reflect on your own experience at the College, and about the friends and instructors who left a lasting impression on you. Meet our students and you will know that we still do well. Extremely well.

When James Wright was acting prestdent of Durtinouihlast spring, he gave a talk to the Alumni Council that at tempted to answer public concerns about higher education. This article is adapted from that speech.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

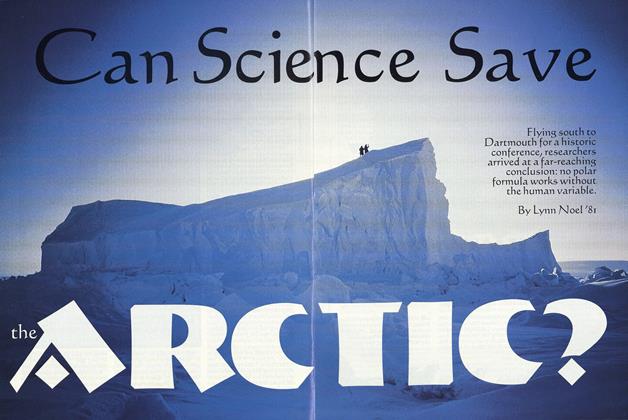

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

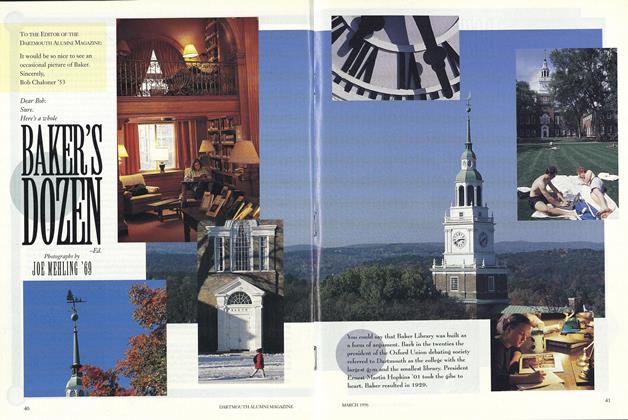

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleSpace Politics

March 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1996 By Armanda Iorio

James Wright

-

Books

BooksFrontier Plans and Dreams

May 1980 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleBuilding Community

APRIL 1999 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

MAY 1999 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

notebook

notebookGood Neighbor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JAMES WRIGHT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

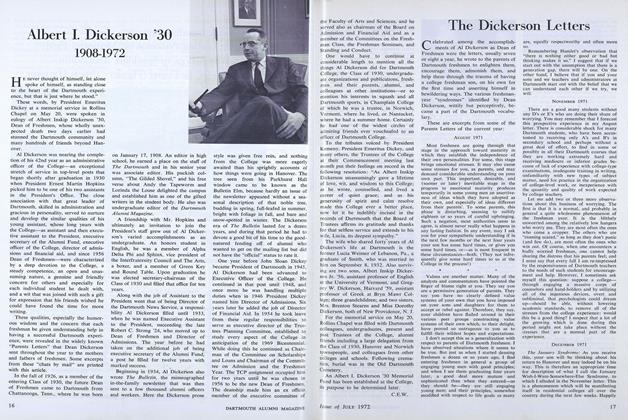

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

JULY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Peripatetic "Silver Fox"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By EDGAR W. McINNIS -

Feature

FeatureThe Broadcasters and the Government

February 1960 By ELMER E. SMEAD