President-elect James Wright must confront escalatingtuition} an extraordinary rate of technological change,and a national debate over diversity. Among other things.

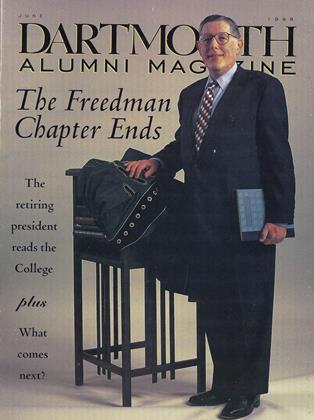

AMES O. FREEDMAN WAS HIRED to bolster the intellectual rigor and reputation of the College. The campus now bears the imprint of his success: new buildings for the chemistry and psychology departments, an expansion of Baker Library, a center for Jewish life. So does the curriculum, overhauled in 1993 for the first time in 70 years, and so, too, the faculty, half of whom were appointed during Freedman's tenure.

President Freedman will hand over a premier undergraduate institution at a time when the rest of the country is rediscovering undergraduates. Applications for the class of 2000 set an all-time record. The student body is more diverse and academically accomplished than at any time in Dartmouth's history. Roughly 50 percent of the last three classes have been female. National rankings routinely place Dartmouth among the top handful of schools in the country. "Dartmouth stock in general is at an all-time high," notes one longtime College observer.

The fiscal shape of the College mirrors its educational shape. The recent capital campaign breezed past its goal of $425 million to raise nearly $570 million. The endowment has climbed above $ 1 billion; the operating budget has been in surplus for seven consecutive years. History professor Jere Daniell '55, who joined the faculty in 1964, reflects succinctly, "Dartmouth is golden now."

The challenge for incoming president Jim Wright '64 A will be maintaining that level of excellence in the face of tremors rumbling through higher education. "There is only one word that embodies it all change, says John Rosenwald '52, former chairman of the Board of Trustees and chair of the recent capital campaign. The new president must confront the escalating cost of tuition, an extraordinary rate of technological change, and an- emotionally charged debate over the value and means of achieving diversity.

At the same time, he must also wrestle with challenges unique to Hanover, particularly the many delicate balances that have made Dartmouth the place it is.

THE HIGH COST OF HIGHER ED

Annual tuition at America's elite colleges and universities has historically cost about the same as a family sedan. In the 1990s the yearly cost of that education was closer to the sticker price on a 3-series BMW (and trending toward the 5-series). The average tuition at private universities increased fivefold between 1976 and 1996. Over the past decade, the net price of college (tuition minus grants and other forms of financial aid) increased twice as fast as median family income. Yet the National Commission on the Cost of Higher Education, in the same report that released those figures last January, surprised many of its sponsors: its research showed that, by and large, fiscal management and pricing policies of American colleges and universities are responsible and sound.

The cost dilemma should be put in perspective. Higher education, particularly at elite schools, is more costly but also more valuable than it has been at any point in history. For many parents, an elite education is the surest bet against an uncertain economic future. We get 17,000 applications for 1,700 spots," says Henry Bienen, president of Northwestern University. Three-quarters of students jointly accepted by Northwestern and the University of Illinois choose Northwestern, despite the fact that North-western's tuition is five times as high. Dartmouth, among the most expensive schools in the country, turns away four students for each one it accepts.

Things that characterize effective undergraduate education at Dartmouth, such as small classes and close working relationships with faculty, are inherently labor intensive. As former Trustee Joe Mathewson '55 points out, "Where schools are under pressure to cut costs, they respond with things—larger classes, videotaped lectures—that are not consonant with Dartmouth." That said, the College has slowed the rate of tuition increases. Next year's tuition hike will be 3.9 percent—the smallest percentage increase in 32 years.

It is not the poorest students who may pass up Dartmouth because of its price tag. Dartmouth remains one of only a handful of institutions in the country that have been able to maintain their commitment to need-blind admission. Rather, Jim Wright must deal with the anxiety of middle-class families, especially those with several children in college, who are feeling increasingly squeezed. "We are now charging $30,000 a year, and that is beyond the reach of many families," says Mathewson.

Princeton boldly changed the rules of the game in January when it unveiled a series of changes in its financial-aid formulas to aid middle-class families, such as no longer including home equity when calculating assets of families earning less than $90,000 a year. Yale and Stanford quickly followed suit with similar programs. Princeton officials said the new plan will cost the university roughly $6 million a year. It could prove far more expensive if it is the opening salvo in a campaign to use financial incentives to attract top students irrespective of financial need. "Whether Dartmouth can afford to do what Princeton did—or wants to do that—is something the next president is going to have to deal with, says Bob Atwell, a consultant for AT. Kearney who was retained to advise the presidential search committee.

Nothing would shake up the Ivy League quite like a price war.

THE WIRED CAMPUS

This writer, who has yet to return to Hanover for a tenth reunion, was in the first class at Dartmouth to use the Macintosh computer—a 128-kilobyte machine with no hard drive. When the class of '88 matriculated, Microsoft had not yet gone public, the Internet was the province of a small cadre of government scientists, and the best place to begin researching a paper was the card catalog. The point is not that the author of this article is getting old; rather, it is that technology is moving at a pace previously unknown in higher education. As former President David McLaughlin '54 notes, "Every major institution has had to reexamine its mission and structure because of changes in technology. Only higher education has not done that."

President Wright will face two technology-related challenges. The first is choosing a path of technology development that is appropriate for the College. Technology will offer extraordinary opportunities to enhance the Dartmouth experience. But how will the College create and limit access? How much investment in what types of systems? And questions with broader implications: What if students were able to tap into a Dartmouth-quality course during an off-term or during the summer before matriculation? Couldn't introductory courses such as calculus be taught that way, shaving a quarter or even a year (and tens of thousands of dollars) off the time spent in Hanover? Technology is both expensive and littered with dead ends. (Dartmouth's marriage to the Macintosh, while the rest of the world has moved toward Windows-based systems, is but one example.) Leadership will mean finding the right cutting edge, and in some cases, it will mean leaving the cutting edge to someone else.

The more crucial objective, and one in which Dartmouth is a natural leader, is translating technology into better teaching. For all its wizardry, the Internet has no more promise than a chalkboard—a tool waiting to be employed by a great teacher. The gains, many of which are already being realized in Hanover, are potentially huge. As Donald Kennedy, former president of Stanford, noted recently, "Cyberspace is not a substitute for personal contact between teacher and student, but it does make possible a level of interaction that would otherwise be inconceivable."

BETWEEN A KEG AND A HARD PLACE

A 1994 Harvard School of Public Health study found that 44 percent of college students nationwide report being binge drinkers, meaning that they have had five drinks in a row on at least one occasion in the previous two weeks. The pathologies associated with binge drinking are more shocking than the drinking itself. Binge drinkers are seven times more likely than non-binge drinkers to have unprotected sex, ten times more likely to drive after drinking, and 11 times more likely to fall behind in school.

The problem is certainly not new to Hanover. In 1920 Robert Meads '20 shot Henry Maroney '19 dead after a dispute over a bottle of bootleg liquor. And, contrary to the public perception, Dartmouth's rate of binge drinking is slightly below the national average. Neither fact is much consolation. "When you talk to alums and Trustees, they can tell you a lot of things they're proud of," says Mathewson. "When you ask what they're not proud of, many will say, frankly, that they're not proud of the drinking, the alcohol abuse."

"I think the next president—with the Trustees—is going to have to address that problem. And I think there is a will to do that," says Bob Atwell, who, in addition to consulting for the Board of Trustees, also has a daughter at the College. Indeed, the Alumni Council voted recently to "lend its moral authority on behalf of the alumni body by supporting the Trustees and the College in their efforts to combat alcohol abuse and binge drinking in particular." But the Wright administration must confront some nettlesome realities. Three-quarters of the student body cannot drink legally. When faced with a similar situation during Prohibition, legend has it that President Hopkins struck a gentlemen's agreement with the region's best-known bootlegger: the College would not pursue legal action provided that students were sold "safe" liquor. Such paternalistic pragmatism is no longer possible. Federal law mandates that the College work to urge students to obey the state drinking age or face a loss of federal funding. Yet cracking down hard on drinking has two serious consequences. First, it drives students to drink off campus, where they may actually face more danger, especially if they are driving. And second, it may cause students to avoid seeking help in life-threatening situations. Last year Virginia Attorney General Richard Cullen broached the subject of lowering the drinking age to 18 after five students died at Virginia state colleges in five weeks. Barring such an unlikely change, the next president inherits a task that has eluded every president in Dartmouth's modern history: changing the campus culture in a way that moderates abusive drinking. There is no other long-term tenable solution .

Alcohol begs the equally contentious and long-standing question of the Greek system. Eliminating the Greek system, or even curtailing it sharply, is probably a nonstarter for a new president, something akin to Bill Clinton's attempt to eliminate the military's ban on gay soldiers. Though Jim Wright comes to the presidency with a long and respected history at Dartmouth, this issue could require more political capital than any new president will have. Instead, both alcohol and fraternity issues are best viewed as part of a broader framework: residential life. On that front, there is some good news. A 1996 survey found that 69 percent of Dartmouth undergraduates felt their social life was pretty good or excellent. Only four percent reported it was poor or terrible. (The survey showed that fraternity and sorority members—who, according to a different survey, drink more than other students—are also the most satisfied with their social lives.) In 1996 the College opened the East Wheelock Cluster, a group of three residence halls and a common area dedicated to integrating academic experiences into other aspects of students' lives. Ideas for creating night-life alternatives to drinking—including expanded uses of the Collis Center—have had mixed results but continue to be an institutional priority. The next president will be keenly aware of the issue. As David McLaughlin says, "The quality of learning outside the classroom is every bit as important as learning in the classroom."

THE DETAILS OF "DIVERSITY"

The last contentious national issue to rear its head in Hanover is diversity, a word at risk of losing what little meaning it has left. President Freedman spoke out widely in favor of affirmative action and the benefits of a diverse student body. As systems such as the University of California have learned, however, the devil is in the details. Is a black student in St. Louis whose parents are both doctors really that different from a white student in Chicago whose parents are lawyers? Is the mission of diversity well served by providing affinity housing based on race? How does Dartmouth maintain its commitment to minority admission in the context of changing national attitudes toward affirmative action? The national debate over diversity has been nasty and strikingly unproductive. At a minimum, Jim Wright must lead the Dartmouth community through these issues. At best, all of higher education—indeed, the country—would benefit enormously from an articulate spokesperson on the subject.

The more immediate task is to ensure that Hanover is an attractive place for women and minorities. In the survey of undergraduates mentioned earlier, African-Americans were least satisfied with their social lives. The number of students of color at Dartmouth continues to lag behind other—particularly urban—schools. "How do you make a place like Hanover attractive to African-American and Hispanic kids?" asks Bob Atwell. "I don't know. That's a tough sell."

To the extent that Dartmouth is already a more hospitable place for women, the College must battle long-standing stereotypes. It has much ammunition. The Women in Science Project has doubled the percentage of women who choose science as a major. Dartmouth is a national leader in the percentage of women participating in intercollegiate athletics, and contributed two members to the women's gold-medal Olympic hockey team. Alas, good news spreads slowly. "I think Dartmouth's reputation as being unfriendly to women lives on in the minds of guidance counselors, in some schools anyway. I think that's a terrible unfairness to Dartmouth," says Mathewson When asked which Ivy League school has the highest proportion of women in tenured and tenure-track faculty positions, how many national opinion leaders would answer correctly that it's Dartmouth?

THE GRAYING ACADEMY

The nation's premier colleges and universities are faculty-driven institutions; for all the noise surrounding the system, tenure is a remarkably solid institution. But there is a related issue catching the attention of university administrators: the graying- of the faculty. In the early nineties federal law was changed to prohibit mandatory retirement on the basis of age for tenured faculty members. As a result, senior faculty have lingered on in many institutions, straining budgets and reducing openings for junior faculty. An aging faculty also widens the distance between teacher and student.

Jere Daniell, who says he intends to retire at 70, notes that Yale has 40 fall professors over the age of 70, half of them holding chairs. Geriatrics don't yet reach those numbers Dartmouth. Nonetheless, Dean of the Faculty Ed Berger noted in his recent annual report that the fraction of faculty holding tenure at Dartmouth has climbed steadily from 48 percent in 1971 to 73 percent today.

SCHOLARS AND DOLLARS

Dartmouth is a market leader in a niche that the rest of the academic world is rediscovering: undergraduate education. "Perhaps the most fundamental thing to be said about the teaching of undergraduates is that its importance is suddenly being more widely recognized," Stanford's Donald Kennedy recently noted. Indeed, a newly-released report by the Carnegie Foundation's Boyer Commission chastises research universities for their "inadequacy, even failure" in educating undergraduates. The College's focus on undergraduate education has been ensured by Dartmouth's long-standing policy that graduate enrollment in the Arts and Sciences should not exceed ten percent of the undergraduate enrollment.

But there is a more nuanced side to the issue. Dartmouth's key resource is great teachers. Great teachers must be active researchers. And active researchers benefit from graduate students, especially in the sciences. "I hope that tension never gets resolved," says Bob Atwell. He reasons that any resolution might neglect undergraduate teaching on the one hand, or chase away good faculty on the other. Managed correctly, world-class. research is not incompatible with outstanding undergraduate education. But it is a balance that must be constantly calibrated. James Freedman enhanced Dartmouth's undergraduate reputation in part because he made the campus attractive for scholars.

That attractiveness has had—like most educational issues these days—a financial implication. The dollar amount of grants awarded to Dartmouth has doubled over the past ten years, from $38 million in 1988 to $78 million in 1997. Jim Wright will be well aware of that increasingly important income. Dealing with arcane accounting requirements for government-funded research is just one of the responsibilities of college presidents today. Like politicians, college presidents must constantly be raising money. No sooner does a capital campaign end than planning for the next one begins. Fundraising has added a grueling and time-consuming part to the president's work load, be it schmoozing alumni on both coasts—and everywhere in between—or addressing organizations and foundations. That, on top of a job that has gotten both more demanding and faster-paced. "Ten years ago a president didn't have to respond to 100 e-mails a day," says Northwestern's Henry Bienen.

Indeed—though President Freedman rarely uses a computer and prefers to communicate non-electronically—the job has evolved at Dartmouth as well. One of the most important legacies of the Freedman administration is a well-kept secret outside of Hanover. James Freedman was the first Dartmouth president to appoint a provost—a chief operating officer whose portfolio is the entire college, including the professional schools. In the Freedman administration, the provost freed the president to step back and focus on larger tasks. Freedman delegated more duties than anyone in the history of his office, notes Jay Heinrichs, editor of this magazine from 1986 to 1997."He focused him-self, sticking to the few goals he stated when he first got hired: improving Dartmouth's intellectual life, research opportunities, and public reputation." His successor will do well to study that administrative style. As it turns out, Jim Wright is already intimately involved with the style—he is currently Dartmouth's provost.

Perhaps the most important lesson of the Freedman presidency is not for his successor, but for the alumni. James O. Freedman proved that Dartmouth can improve and adapt without compromising all that makes it unique. Freedman's early detractors worried publicly that an outsider, particularly a Harvard man charged with upgrading the intellectual rigor of the College, would somehow erode Dartmouth's tradition or spirit. That has not been the case. In fact, for all the talk about "Harvardizing" Dartmouth, the irony is that Jim Freedman has chosen to stay in Hanover after he steps down.

"In the 1990sthe yearly costof an elite collegeeducation wasclose to thesticker price on a3-series BMW."

"When you askwhat alumni arenot proud of,many will say,frankly, thatthey're not proudof the drinking."

"The immediatetask is to ensurethat Hanover is anattractive place forwomen andminorities."

"Like politicians,college presidentstoday mustconstantly beraising money."

CHARLES WHEELAN is the Midwest correspondent for The Economist. He holds a master'sdegree in public affairs from Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School and a Ph.D. in public policyfrom the University of Chicago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

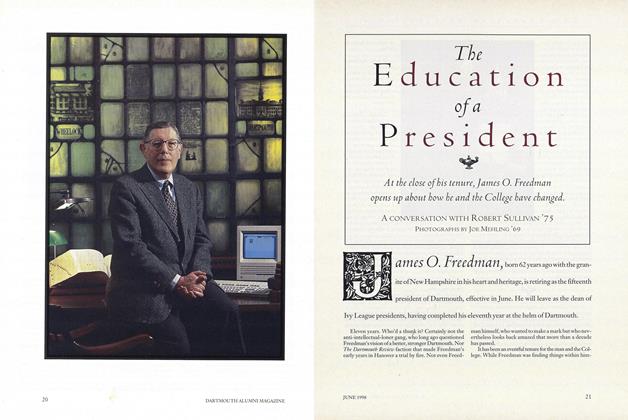

Cover StoryThe Education of a President

June 1998 -

Feature

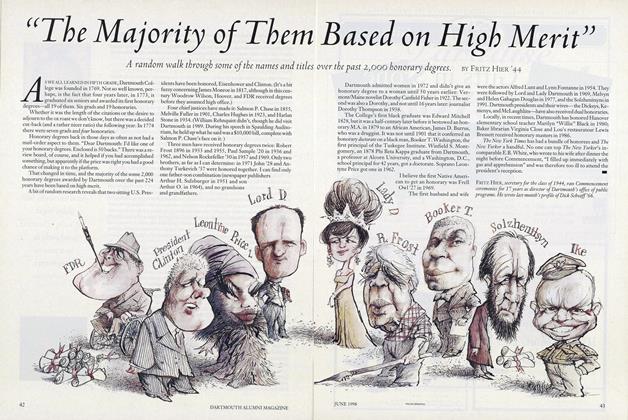

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

June 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleThe Gospel According to Odysseus

June 1998 By Professor William Scott -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

June 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNewt ana Other Spring Speakers

June 1998 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1998 By Don Casey Jr.

Charles Wheelan ’88

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

OCTOBER 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureHitting His Stride

February 1992 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

NOVEMBER 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

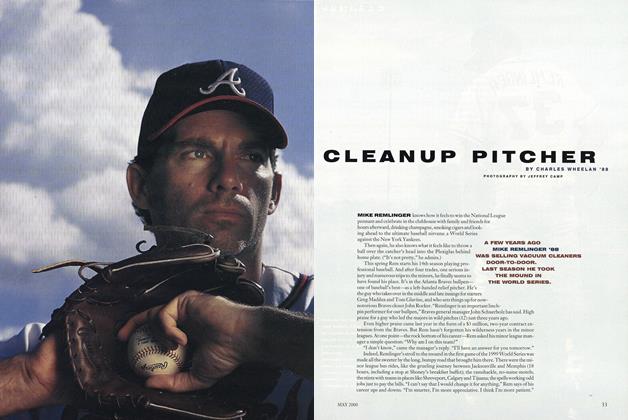

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

MAY 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1961 -

Feature

FeatureVincent Starzinger Professor of Government 1,000 miles in o single scull

January 1975 -

Feature

Featureclassnotes

MAY | JUNE 2016 -

Feature

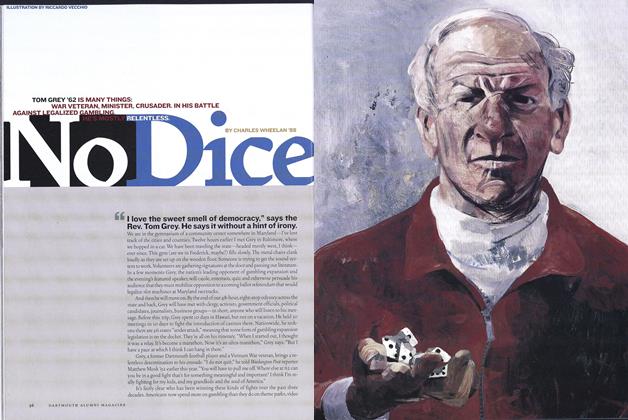

FeatureNo Dice

July/Aug 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

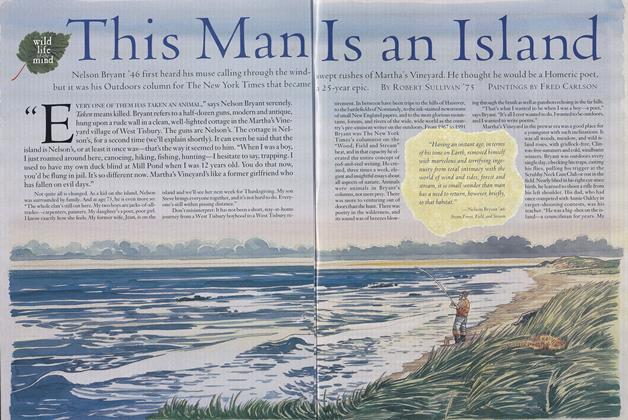

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75